Editor’s note: November is Native American Heritage Month. First proclaimed by President George H. W. Bush in 1990, it is an opportunity to acknowledge the histories and cultures of Native people across the U.S., highlighting the challenges they have faced, their sacrifices and their contributions.

“Native Americans have influenced every stage of America's development,” noted President Donald Trump in his October 31, 2017 proclamation. “They helped early European settlers survive and thrive in a new land. They contributed democratic ideas to our constitutional framers. And, for more than 200 years, they have bravely answered the call to defend our Nation, serving with distinction in every branch of the United States Armed Forces.”

This month, VOA will highlight some of the more prominent figures in Native American history and their contributions to U.S. language and culture.

Tisquantum, more popularly known as Squanto, was a member of the Patuxet band of Wampanoag in what is today the northeastern state of Massachusetts. Born some time before 1600, he is best known for having acted as an interpreter and guide to British settlers, members of a separatist Christian sect who had sailed aboard the ship “Mayflower” from England in 1620 to establish a new religious colony.

While Squanto figures in several early narratives, scholars still disagree on many facts of his life. At some point during the first two decades of the 17th century, an English adventurer kidnapped Squanto and about two dozen other Wampanoag by tricking them into boarding an English trading ship. The English beat them and tied them up, then sailed for Spain to sell the captives as slaves.

Here the tale gets fuzzy: In one version, Spanish monks enabled Squanto’s escape from Spain to England. In others, a ship captain took him from Spain to London and later Newfoundland, where he lived among the English for several years and learned the language.

What is certain is that Squanto accompanied an English merchant named Thomas Dermer, who sailed to New England to establish trade relations with Native tribes. When they arrived, they discovered that tribal villages were all but empty, their residents dead from an epidemic which historians say decimated populations across southeastern Massachusetts between 1616 and 1619.

Even Squanto’s own home village had not been spared, according to Dermer, who wrote—in words that reflected the colonialist’s view of America’s Natives at the time—“When [we] arrived at my savage’s native country [we found] all dead.”

Squanto acted as an interpreter and cultural advisor to Dermer, and interceded when Dermer was attacked or taken captive by tribes suspicious of his motives.

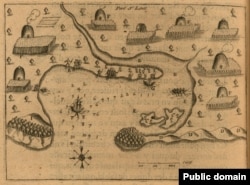

In 1620, a group of religious separatists from England who had been living in exile in the Netherlands—two centuries later dubbed Pilgrims—gained financing in order to make the trip to the New World, where they hoped to establish a farming colony. After more than 60 days at sea, they arrived in Massachusetts that November. They settled at the site of Squanto’s former village, which they renamed New Plymouth.

Squanto is best known for helping the newcomers through that first harsh winter. William Bradford, the leader of the Plymouth colony, characterized Squanto as a “special instrument sent of God.”

"Squanto continued to stay with us, whose help could never be fully thanked or repaid,” Bradford wrote. “Squanto directed us in how to set our corn, where to take fish, to procure other commodities, took us various places for our benefit, and never left us until his death.”

Squanto also served as an intermediary between the English and the Wampanoag, helping negotiate trade and a peace deal. And he introduced the Plymouth colony to fur trapping, which helped them earn money and pay off the individuals who had financed their trip to the New World.

He is also associated with what has come to be known as America’s first Thanksgiving: In the fall of 1621, the colonists and dozens of Wampanoag held a three-day celebration of a successful autumn harvest.

Squanto was later accused of stirring up hostilities between the English and the Wampanoag, whose chief demanded Squanto be handed over and executed. From then on, Squanto was alienated from his own people and it appears that the Wampanoag cut off provisions to the settlers.

In November 1622, Squanto sailed with a group of settlers to trade with a group of Natives across the Cape Cod Bay from Plymouth. There, he fell sick and died of what Bradford called “Indian fever.”

“…and bequeathed sundry [various] of his things to sundry of his English friends, as remembrances of his love,” wrote Bradford, “of whom they had a great loss.”

The details of Squanto’s life, while scant, speak of that moment of first contact between Europeans and America’s tribal people. It isn’t known why Squanto helped the settlers or whether he had much choice in the matter. It’s clear the Pilgrims were grateful to Squanto and felt some degree of affection toward him for having ensured their survival in a new world. And it’s also clear that unknowingly, Squanto helped open the floodgates to waves of new English settlers and the ultimate subjugation of hundreds of tribes across the continent.