If you were able to go back in time and tell sports fans of the late 1930s and early 1940s that a young Black athlete would become an American icon for breaking a color barrier, they’d likely think you were talking about Kenny Washington. Few would imagine you were describing Jackie Robinson, who followed Washington at UCLA as a football and baseball player. In 1940, a Los Angeles Times sports writer worried that Washington was irreplaceable on the gridiron. “It is going to take a piece of doing,” he wrote, “for Jackie Robinson to fill his shoes.”

Today, it’s Washington who’s been engulfed by Robinson’s shadow. In the decades since Washington broke the NFL’s color barrier in 1946—the year before Robinson got to the Brooklyn Dodgers—the league has hardly acknowledged his importance, especially compared with the way Major League Baseball has burnished Robinson’s legend. A 2006 exhibition at the Pro Football Hall of Fame called “Breaking Through: The Reintegration of Pro Football” focused on the Cleveland Browns’ Marion Motley and Bill Willis—half of the sport’s “forgotten four” of pioneering Black players, along with Washington and Woody Strode (who signed with the Los Angeles Rams two months after Washington). In 1946, Motley and Willis integrated the All-America Football Conference, a newly formed league that launched without a color barrier. Washington, meanwhile, was the first of the four to integrate pro football.

This year is the 75th anniversary of Washington’s groundbreaking season, and he’s barely a footnote in the annals of sports history. During the lead-up to this past Super Bowl, a CBS segment at last acknowledged his singular breakthrough—calling it a “Jackie Robinson moment.” So why, all these decades later, don’t we talk about Jackie Robinson’s debut as a “Kenny Washington moment”? Why did America forget Kenny Washington?

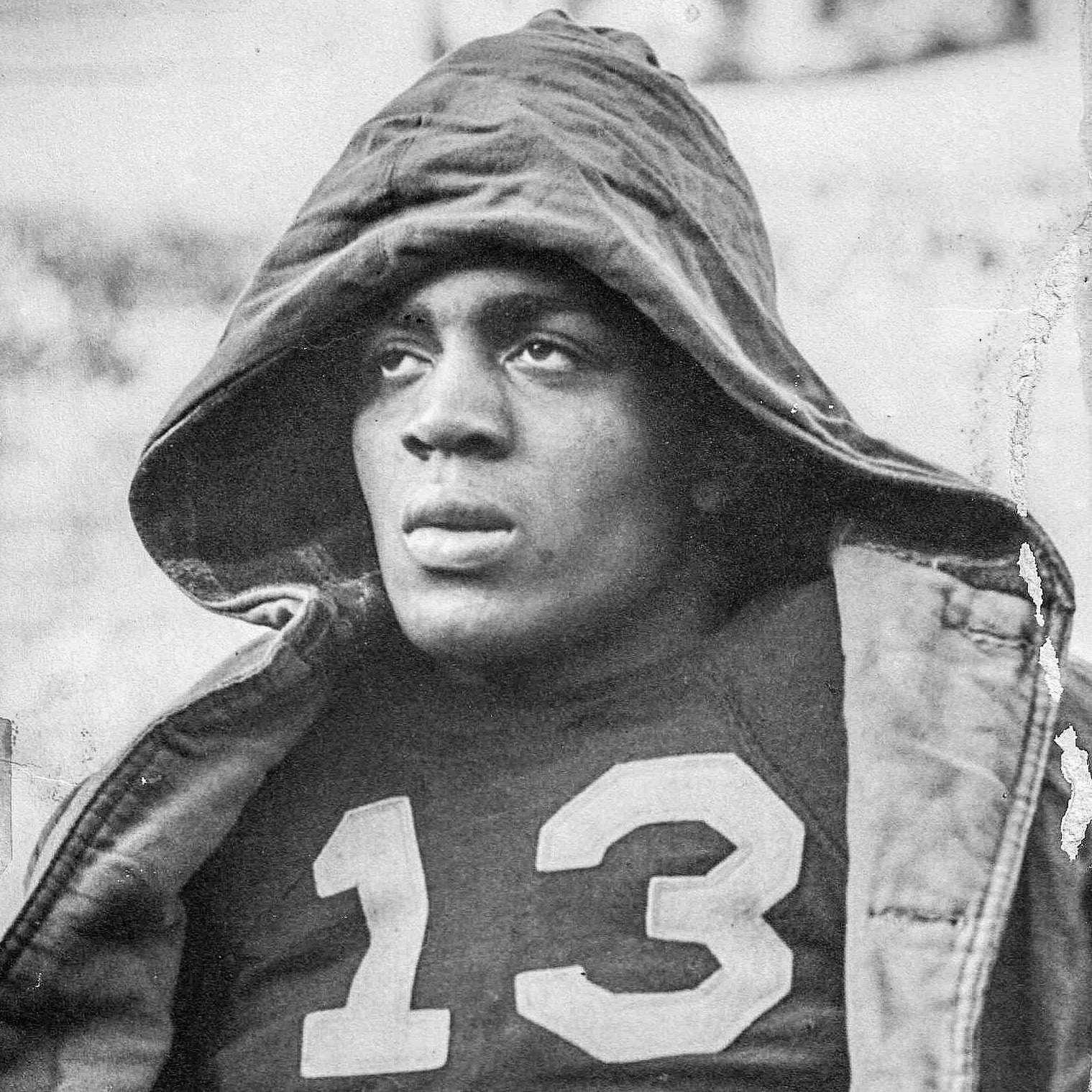

Washington was born in 1918 in Los Angeles, the only child of a Black American father and a Jamaican mother. He grew up in the predominantly Italian neighborhood of Lincoln Heights, the city’s first suburb. Raised by his grandmother Susie and his aunt Hazel and uncle Roscoe (“Rocky”) Washington, the young Kenny broke both knees in a bicycle accident at age 10, but was still a gifted athlete. He became a Los Angeles sports hero in 1935 when he led Lincoln High School to city baseball and football titles.

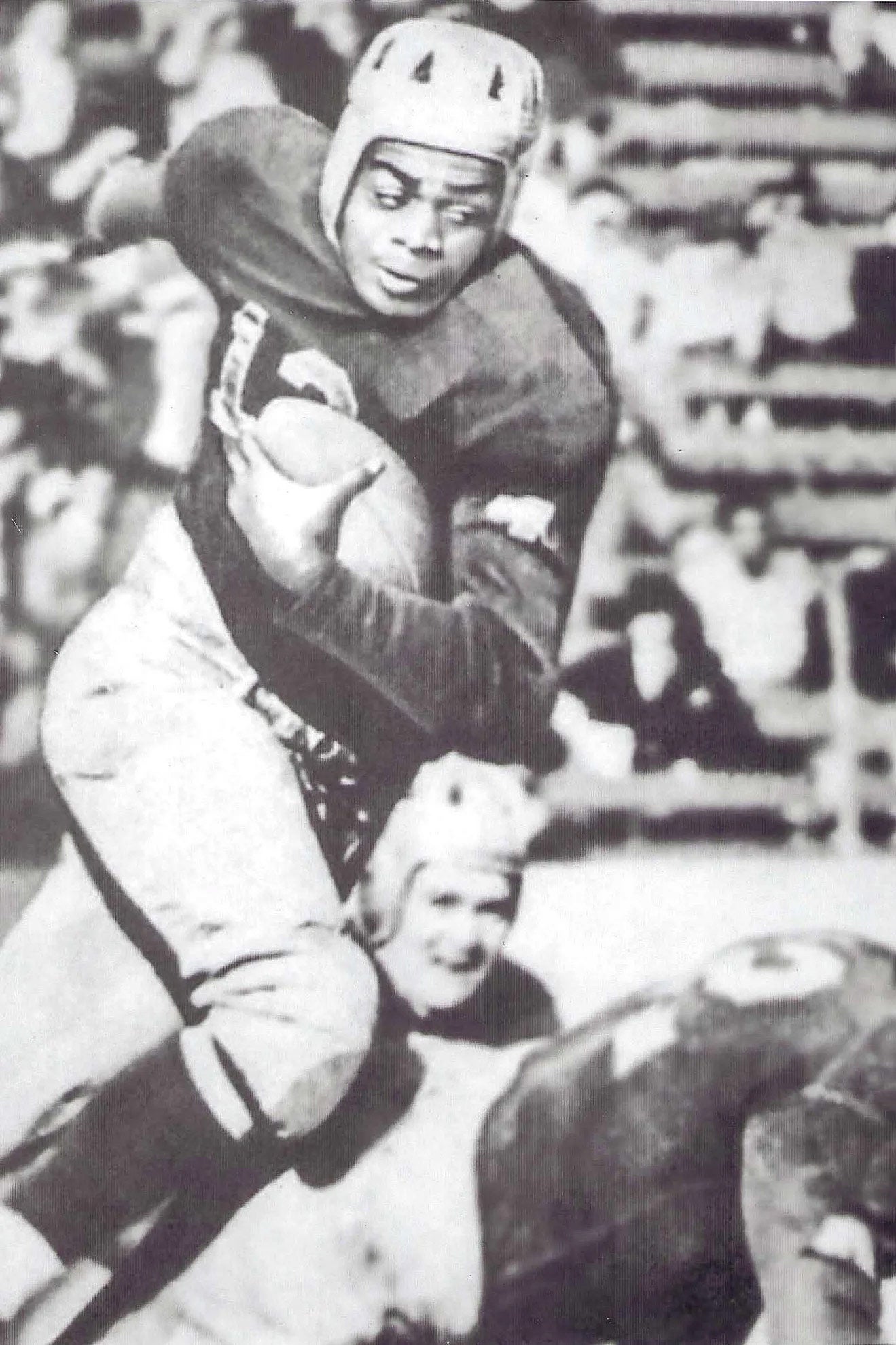

Washington continued his baseball career at UCLA, batting .454 and .350 for the Bruins in 1937 and 1938. But it would be on the football field that he’d achieve his greatest success, becoming a national figure on the most racially integrated squad of its era. Washington was a single-wing halfback, in a role not unlike that of a modern-day quarterback in an option-style offense. He was the team’s field general, and the Los Angeles Times took to calling him “General Washington.”

Jackie Robinson, a junior college transfer from Pasadena, came to UCLA in 1939, the year Washington won the Douglas Fairbanks Trophy as the nation’s best college football player. On the surface, the two shared much in common. Both were multisport stars who grew up in predominantly white, middle-class, Los Angeles neighborhoods (approximately 6 miles apart). Yet the young men were fundamentally different people. Washington was gregarious, a big man on campus. Robinson, meanwhile, had run with a gang and been in trouble with the police, and never quite bonded with teammates; years later, John Gregory Dunne wrote that he “needed adversaries the way most people need friends.” Given their dispositions, it makes sense that Washington and Robinson had a chilly relationship at UCLA. There were even rumors about a fisticuffs in a Westwood alley. As Arnold Rampersad recounts in his biography of Robinson, the gossip had so much traction that Robinson felt obliged to address it, claiming he was too smart to mix it up with a man of Washington’s size and strength.

But it wasn’t just their personalities that set the two men apart. Even in college, they had fundamentally different attitudes about race. Washington was accommodationist and reluctant to stir the pot. While sitting on the Student Council at UCLA, he became embroiled in a controversy over a campus theater production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which some student activists worried would traffic in racist stereotypes; Washington headed a committee that determined that the production was “simply a play full of grand entertainment.” Bill Ackerman, UCLA’s athletic director, praised Washington for being “liberal-minded and full of common sense.” Robinson, meanwhile, had recently come under the influence of the Rev. Karl Downs of Scott United Methodist Church in Pasadena. Downs was an activist who had published a call to arms, “Timid Negro Students!” in the magazine of the NAACP, arguing that by substituting “courage” for “timidity,” young Black people could help end injustice. The reverend’s influence upon Robinson was clear during his college years: Robinson had little patience for inequality. According to Hank Shatford of the Pasadena Junior College Chronicle, “When [Robinson] felt he was right and the other guy was wrong, he didn’t hesitate. He was in there.”

While Washington was embraced on campus, Robinson was held at arm’s length, in part due to a run-in with a motorcycle policeman in Pasadena in September 1939 immediately before he arrived at UCLA. Somehow, having a gun pulled on him after a white motorist called him and his friends the N-word marked him as dangerous at UCLA. “It was pretty hard to shake off,” he told Rampersad. Not surprisingly, Washington (with an uncle in the Los Angeles Police Department) became the more prominent media figure at the time—especially among white journalists. As Claude Newman wrote in the Sun Valley Times years later, “With such men [as Washington] there are no racial problems. Would that there would be more like him.”

On the field, though, Washington and Robinson were a perfect match. They led the Bruins to a 6–0–4 record and within 4 yards of defeating intracity (and all-white) rival USC and earning a trip to the Rose Bowl. When UCLA’s head coach took Washington out of that USC game with 15 seconds to play, fans in the packed Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum stood and applauded for what seemed like an eternity. As UCLA teammate Woody Strode put it in his autobiography, Goal Dust, “It was the most soul-stirring event I have ever seen in sports. Someone told me that [future Oscar-winning actress] Jane Wyman was crying in the stands. And as Kenny left the field and headed to the tunnel, the ovation followed him in huge waves. It was like the Pope of Rome had come out.”

At the very moment that Washington soaked in the love from the Coliseum crowd, the 1940 NFL draft was taking place at the Schroeder Hotel in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. A handful of Black players had competed in the NFL during the league’s first 13 years of existence, but the league’s owners enacted a “gentleman’s agreement” in 1933, unofficially banning Black players. Therefore, it was no surprise that, as college football fans celebrated Kenny Washington, the NFL’s 10 teams ignored him, through 22 rounds. NBC Radio commentator Sam Balter excoriated the league on his nationwide show, Inside of Sports: “[Washington] would be the greatest sensation in pro league history. […] He was No. 1 on all your lists. None of you chose him.”

Bypassed by the NFL, Washington took his talents to Hollywood. It was a logical next step: His father, Edgar “Blue” Washington (a former boxer and Negro League baseball player), had at that point appeared in more than 50 movies, and his aunt Hazel was actress Rosalind Russell’s personal assistant. Washington received $2,500 to star in While Thousands Cheer, a 1940 crime drama that follows college football hero Kenny Harrington’s efforts to bust up a game-fixing ring. Though there are no known copies of the film in existence, it seems to possess roughly the same plot as 1931’s The Galloping Ghost starring Red Grange, the greatest player of his age. Historian Michael Oriard notes that While Thousands Cheer was the only one out of 120 full-length football films produced between 1920 and 1960 to feature a Black star.

Around that time, the integrated, semipro Pacific Coast Professional Football League was getting off the ground. Washington signed with the Hollywood Bears and soon became the league’s headliner. He would take in as much as $500 per game in the PCPFL, plus a percentage of ticket sales. At the time, Don Hutson, the NFL’s biggest star, earned only $175 per game.

Back at UCLA, Robinson struggled to fill Washington’s shoes, just as the Los Angeles Times had predicted. After taking over Washington’s single-wing halfback position in 1940, Robinson led UCLA in passing and rushing, but the Bruins finished just 1–9. On the baseball diamond, the falloff would be even more glaring. Robinson, who succeeded Washington as the Bruins’ shortstop, hit just .097 in his only college season.

When the 1940 football season ended, Robinson again followed Washington’s lead, leaving UCLA prior to graduating and, after a brief stint playing football in Hawaii, joining the PCPFL’s Los Angeles Bulldogs. The two faced off against each other on Dec. 21, 1941, with Washington tossing a 55-yard pass to Strode to defeat Robinson’s Bulldogs.

When World War II started, Robinson enlisted in the Army, but knee surgery kept Washington out of the service and sidelined him from football. By this point, Washington had a wife (the former June Bradley) and infant son (Kenny Jr., born in 1941) to support. At a crossroads, he followed the lead of his uncle Rocky, the first Black lieutenant watch commander in the LAPD. After placing 39th out of 1,837 candidates who took the department’s entrance exam, Kenny joined the force in April 1942 and was appointed to the motorcycle detail a month later. He served under Rocky at the Newton Street Division, located amid nightclubs, barbecue joints, and bustling foot traffic. But Washington wasn’t satisfied with his largely symbolic role, where his duties included talking to kids about the importance of staying in school and playing for the LAPD baseball team.

“He wasn’t cut out for law enforcement,” said his daughter Karin Washington Cohen. Karin explained that her mother June had told her that Kenny’s time on the force was likely the angriest period of his life. He gambled on horse racing and wasn’t home a lot, and June eventually filed for divorce.

Frustrated with police work, Washington returned to football in 1944, playing for the San Francisco Clippers of the American Football League, a West Coast league in direct competition with the PCPFL. He soon reestablished himself as the most dominant player outside the NFL, leading the Hollywood Bears (whom he rejoined in October 1945) to a league championship. And so it made sense that in 1946, when the Cleveland Rams wanted to relocate to Los Angeles to play in the 103,000-seat, publicly owned L.A. Memorial Coliseum, a group of Black journalists prodded the team to give Washington a tryout. Rams general manager Charles “Chile” Walsh hemmed and hawed, publicly vowing that the Rams would not bar any player on the basis of race, but privately fearing a racist backlash from owners around the league.

The Black sports writers who stumped for Washington weren’t naïve. They knew that Washington, who was 27 years old and preparing for his fifth knee operation, was nearing the end of his career. “Of course, Kenny hasn’t got a whole lot of years on the gridiron ahead of him, but we’ll string along with him for our money’s worth, never having been robbed yet,” wrote Washington’s most vocal advocate, Halley Harding, a Los Angeles Tribune sports writer.

The campaign worked: Washington signed with the Rams on March 21, 1946. The integration of pro football garnered national attention, and Washington was celebrated by both the mainstream and Black press, though the leaguewide ban that precipitated his signing was rarely mentioned—if not outright denied—by white writers. Dick Hyland, an L.A. Times columnist who’d asked his readers in 1941 whether Kenny Washington might be the greatest football player who ever lived, asserted in 1946 that the NFL “has never had a rule against the use of Negro players.”

Washington’s signing was celebrated in Los Angeles’ Black community, where the football star was honored by churches and civic groups, and Kenny and June (who had since reconciled) were fêted by high society. But the optimism that followed his signing was offset by Washington’s ongoing knee woes. After surgery in April 1946, he rode a bicycle as much as he could to get his legs back into playing shape. However, not long after reporting to Rams training camp in late July 1946, he again tweaked his knee. By mid-August, he had to have fluid drained from it and was forced to wear a clunky steel brace. There were whispers that the Rams might end up cutting Washington before the season began.

He missed an intrasquad scrimmage, but made his NFL debut in a Chicago exhibition game between the Rams and a college all-star team. Fans called for the Rams to sub in Washington throughout the game, and head coach Adam Walsh finally gave in with five minutes to play. As the Los Angeles Tribune’s Harding wrote of one Washington highlight, “Even with his gimpy leg he went through the line for 12 yards, dragging half the opposition along.”

His first Rams appearance in Los Angeles came in their next exhibition game against the Washington football team. By all accounts, he received an unusually large ovation when he walked onto the field. Some white writers harped on the racial makeup of the cheering crowd. Gordon Macker of the Los Angeles Daily News, for instance, mused that the signings of Washington and Woody Strode seemed like a publicity stunt to fill the cavernous Coliseum with Black patrons, given Washington’s underwhelming performance in the game (and the fact that Strode never saw the field). “Just to sign ’em to win the affection of (not to mention the business) of Halley Harding’s customers,” Macker wrote, “and then only use ’em on the billboards and splinters is strictly four ball …[a] skam of advertising.”

Continuing to be plagued by his knee, Washington would play in only six of 11 regular-season games in 1946. Following that season, many in the white press suggested that Washington ought to retire or that the Rams should cut him. (Strode was cut before the 1947 season.) In the Black press, the spotlight shifted to Robinson, who debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers in April 1947. As Robinson became a star in America’s most beloved sport, Washington quietly had his most productive NFL season, averaging 7.4 yards per carry in limited duty. At times, he even showed sparks of his former self. His 92-yard touchdown run against the Chicago Cardinals is still the longest run from scrimmage in Rams franchise history.

Washington’s return to form was short-lived. He reinjured his knee against the Chicago Cardinals in November 1947 and was never the same. He played more sparingly in 1948, and the weight of public scrutiny began to take a toll on him. That preseason, the Rams were scheduled to play the reigning NFL champion Philadelphia Eagles in an exhibition game in Dallas, the first integrated professional football game in the Deep South. Washington initially refused to participate, fearing threats to his personal safety. But he eventually gave in, and rushed for 60 yards in a contest that went off without any major incidents—though the 500 Black fans in attendance were forced to sit in segregated seating in the end zone. In October 1948, around the time of the release of Rogues’ Regiment, a film in which he co-starred, Washington told the Pittsburgh Courier that he now preferred acting over football.

Like Robinson’s well-chronicled experience in Major League Baseball, Washington suffered his share of slurs and cheap shots in the NFL—perhaps more than he had while playing for UCLA or in the PCPFL, when he was less likely to compete against players from the South. But unlike Robinson, Washington publicly shared very little about the indignities he experienced on the field. Most of what we know comes via his teammates. According to Rams halfback Tom Harmon, a Green Bay Packers player elbowed Washington in the jaw in a 1947 game, then called Washington a “Black bastard.” Washington replied: “I want to tell you something, you white trash. If you want to wait till the game is over, meet me under the stadium and I’ll knock your goddamn block off.” In the following game, an opponent tried to kick Washington in the head as he was lying on the ground, though he was able to dodge the blow. When his white teammate Jim Hardy (whom I interviewed before his death in 2019) later asked him about the incident, Washington replied in a rare moment of candor, “It’s hell being a Negro, Jim.”

Washington also dealt with injustice off the field. In Goal Dust, Woody Strode writes of the Rams’ two Black players being turned away at the team hotel room prior to an exhibition game in Chicago. Strode and Washington managed to find a hotel on the Black side of town where Count Basie happened to be performing. When teammate Bob Waterfield tracked them down and urged them to come back to the original hotel and be with their team, Washington and Strode held up their Tom Collinses, gestured to Basie, and told Waterfield that they’d rather “stay segregated.” (In contrast, Jackie Robinson forced the issue when he was told he could not stay with the rest of the Dodgers at the Chase Park Hotel in St. Louis. Robinson wrote in his memoir, “I was tired of having special Jim Crow living arrangements,” and that he “made the hotel back down.”)

Toward the end of the 1948 season, it became clear that Washington’s NFL career was coming to a close. That December, Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron issued an official proclamation: “In recognition of your 16 years as a great football player, your fine conduct and inspirational sportsmanship and your record as Policeman in curbing juvenile delinquency, the city of Los Angeles will recognize officially Dec. 12 as Kenny Washington Day.” At halftime of the last game of the 1948 season, a throng of civic leaders and Washington’s former coaches gathered with him at the 50-yard line. There, the Helms Athletic Foundation presented him with a trophy, a television set, a Ford sedan, and a $500 contribution to his son’s college fund. “Football has been good to me. The cheers you have given me went to my heart and not my head,” Washington told the crowd.

Dorothea Fearonce, a columnist for the Black newspaper the California Eagle, wrote, “It would have made me much happier if the television announcer had said of Kenny that he is a tribute to ‘America,’ instead of a tribute to his RACE!” An AP story about Washington’s NFL farewell included a bittersweet quote from his 1947 head coach Bob Snyder: “Kenny would have been the greatest player of all time, and that includes Thorpe, Nagurski, Nevers and the rest, if he had played in the National league as soon as he got out of college in 1939.”

That’s how Kenny Washington was talked about by those who saw him play. In the decades that followed, Washington’s struggles, and his pioneering role in NFL history, would barely be discussed at all. As Strode said in an unpublished interview before he died in 1994, “History doesn’t know who we are. Kenny was one of the greatest backs in the history of the game, and kids today have no idea who he is.”

Growing up in Los Angeles County in the 1970s and 1980s, Kirk Washington knew that his grandfather had been a beloved athlete. But Kirk can’t remember ever hearing about Kenny Washington breaking the NFL color barrier. It was not until Alexander Wolff’s 2009 Sports Illustrated story “The NFL’s Jackie Robinson” that Kirk realized his grandfather had done something of historical significance.

It makes sense that the end of segregation in the NFL would’ve caused less of a splash at the time, given that pro football was comparatively a fringe sport. But as the NFL has overtaken Major League Baseball in popularity, Washington’s stature hasn’t grown along with the league’s.

Wolff theorizes that we’ve forgotten Kenny Washington because his story is one of rupture rather than redemption. Baseball feels vindicated by Robinson. Its hallowed diamond would be a place—at least, a simplified version of his story suggests—where, in the long run, merit is rewarded and fairness reigns. Pro football has a harder time using Kenny Washington’s story to make such a case. Though they were both 27 years old when they made history, Robinson was still in his prime while Washington, given the state of his knees, was a shadow of his former self. Robinson won Rookie of the Year, an MVP award, and a World Series as a Brooklyn Dodger. Washington didn’t take home any hardware in the NFL.

But there’s another reason the Kenny Washington story may be less palatable to many as American mythology: It doesn’t feature a white savior. Chile Walsh, the Rams general manager, did not crusade on Washington’s behalf the way Branch Rickey did for Jackie Robinson. The Black journalists who led a grassroots movement to pressure the Coliseum Commission and the Rams into signing “our Kenny Washington” are the heroic champions in this tale. The white writers and coaches and executives whom Washington encountered were at best passive observers and at worst outright villains.

Washington also never really embraced being a “trailblazer.” He lived through the same indignities that Robinson faced—violence, taunts, the humiliations of segregation—without ever getting any sense that the league appreciated his struggle, even after his football career had long ended.

Perhaps the greatest symbol of Washington’s historical erasure was his appearance in 1950’s The Jackie Robinson Story. He has an uneventful bit part in the film as Robinson’s Negro League manager. But watch closely, and you may notice him in another scene, this one establishing Robinson’s football cred. The film cuts to actual UCLA game footage of Kenny Washington carrying the ball and getting tackled. It then switches, not so seamlessly, to a shot of what’s supposed to be the same player getting up from the ground. But he’s been replaced by a different man: Jackie Robinson.

The same year he played a bit role in Robinson’s biopic, Kenny Washington made an ill-fated attempt to play Major League Baseball, finagling an invitation to the New York Giants’ spring training. But in less than a week, he was given his walking papers. Given his popularity, it is no surprise that politicians soon sought him out. When Fletcher Bowron, the L.A. mayor who had issued the “Kenny Washington Day” proclamation in 1948, was running for reelection in 1949, he appointed Washington to monitor claims of police brutality in the minority community. The following year, Washington campaigned on behalf of Richard Nixon in his Senate bid. Nixon even spent election night drinking beer with Washington at his home, likely a stunt aimed at getting out the Black vote. Soon, Washington dipped his own toe into politics, failing in a bid to become supervisor of L.A.’s 2nd District. He became a sales rep for Young’s Market, a local liquor distributor, and then joined the public relations department for Cutty Sark Scotch whisky.

Not long after the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles in 1958, Washington became a part-time scout for the team. For a decade, his implicit task was finding the next Jackie Robinson. Working under head of scouting Al Campanis in 1964, Washington helped convince outfielder Willie Crawford to bypass a promising college football career and sign with the Dodgers. That same year, he and June divorced, and Kenny moved out of their Baldwin Hills home and into an apartment not far away. Washington also gravitated back toward the neighborhood where he was raised. In the 1950s and ’60s, he would sit at the end of the bench of his beloved Lincoln High School Tigers, cheering on the football team he willed to a city championship in 1935.

Robinson went on to become one of the country’s leading civil rights figures; journalist Sridhar Pappu has written that he provided a blueprint for the militancy of Malcolm X. Meanwhile Washington continued to believe in gradualism. He’d give to his community, helping to raise money for the local YMCA or a local hospital. And he distanced himself from Nixon in the early 1960s, before Robinson did—but he didn’t, as Robinson did, march on Washington in 1963 or travel to Birmingham in support of desegregation. In 1967, Washington told the Sacramento Bee that young minorities needed to be more patient about the rate of change in America. “They must educate and improve themselves so they can make a decent living. This is the real answer to ending discrimination,” he said. Thus, Washington kept his distance from the Black liberation movements of the 1960s. I think this is what his daughter Karin means when she tells me that her father “wasn’t political.” According to sociologist and activist Harry Edwards, who has studied the history of Black athletes, “Kenny Washington’s mistake was an honest mistake. He held out all of his life clinging to that notion that if we can demonstrate our decency, our discipline, our competitiveness, our intellectual capability and commitment, and our subscription to law and order, we too will be accepted as equals—we too will be considered legitimate as human beings and citizens in this country. […] Of course, it was a pipe dream.”

Longtime NFL referee Jim Tunney, whose father coached Washington at Lincoln High School, remembers bumping into the football legend toward the end of his life. “He was down on his luck,” Tunney remembers. Washington’s health deteriorated, and he reportedly struggled to pay his medical bills. June invited him back into their home in Baldwin Hills, rationalizing to herself, according to daughter Karin, “that there was no one else to take care of him.” In October 1970, a benefit was held at the Hollywood Palladium to raise money for his care. When Washington died on June 24, 1971, at age 52 from polyarteritis (an inflammation of the arteries), A.S. “Doc” Young wrote in the Chicago Defender: “He wasn’t one to complain. But he knew life, too, had curved him. He was born too soon. He died early. Life beat him up. Death kicked him when he was down.” Robinson, who himself would die the following year at the age of 53, remembered Washington in the magazine Gridiron: “He had a deep hurt over the fact that he never had become a national figure in professional sports.”

It’s unfair to the memory of Kenny Washington to frame his desegregation of the NFL as a “Jackie Robinson moment” when, if anything, it’s the other way around. But perhaps it’s a mistake to equate them at all. Despite their similar backgrounds, their shared educations, and their mirrored experiences dealing with the abuses of a racist system—not to mention their athletic prowess—their lives and experiences are so different. It’s possible that Jackie’s story gripped the white American imagination in part because it can so easily be twisted to make us feel like this country has overcome its “original sin”: the Black trailblazer who crusaded to change a racist country and was widely embraced as a cultural hero. Kenny’s story—complicated, messy, and sad—resists easy narrativizing.

It is difficult to imagine more than a handful of men having a greater impact on the league, and yet there’s no “Kenny Washington Day” in the NFL when everyone wears his No. 13. No schools, interstates, or asteroids are named after him. No museums are being built as permanent tributes to his legacy. Forget about a two-part, four-hour PBS documentary—there is not a single feature film that tells Washington’s story. Nor are there any books that treat him as anything more than one piece of a larger narrative about the “forgotten four.”

The NFL’s informal ban of Black players in 1933 seemed to emulate Major League Baseball’s color barrier. But the NFL usurped Major League Baseball as the nation’s sports obsession in part because Kenny Washington broke that same barrier. Washington’s signing was not just a civil rights breakthrough. In helping to establish the Rams franchise on the West Coast, it made the National Football League truly national. Seventy-five years ago, when Major League Baseball was entirely east of the Mississippi River and Jackie Robinson was still playing north of the border for the Montreal Royals, Kenny Washington was in a Los Angeles Rams uniform, trotting onto the grass of the Coliseum.

MLB trotted out “Jackie Robinson Day” in 2004, at least partially to divert attention from the controversy around the use of performance enhancing drugs that blew up that year. Similarly, the NFL may now have an incentive to tell Washington’s story more prominently, to mollify the blowback that the league has earned for its craven treatment of Colin Kaepernick, Black Lives Matter–aligned protesters, and former Black players suffering from brain injuries. According to Stephen Sariñana-Lampson, the president of the Kenny Washington Stadium Foundation, Washington’s story will be celebrated on Jan. 9, 2022—the final Sunday of the NFL season—when the Los Angeles Rams take the field wearing a decal on their helmets to commemorate the 75th anniversary of Washington’s signing with the team. It’s a public acknowledgment that should help bring more attention to Washington’s legacy at last. But there’s a bittersweetness to it, too. There will likely be a brief announcement on the public address system at SoFi Stadium, a graphic for the television audience, maybe even a testimonial from a current player about what Washington means to him, along with advertisements of the NFL’s #inspirechange social justice hashtag. Decades after Washington’s death, the NFL seems to have decided that football fans are now primed to consume his story, and so they’re feeding it to them. But what exactly will NFL fans be digesting? The story of one man’s historic talent, thwarted potential, and confounding contradictions—or another Jackie Robinson?