Movies produced in Pakistan don't typically feature female protagonists, religious minorities, or sensitive men, and they do not reach international audiences. The 2018 film Cake — not to be confused with the 2014 Jennifer Aniston vehicle — has been rewarded for breaking all those rules, and in doing so, has also broken through to viewers beyond the Indian subcontinent. Set between the bustle of Karachi and the hush of a family farm, this colorful dramedy follows the tense reunion of the Jamali sisters as they tend to their aging parents, exorcise family secrets, and explore forbidden romances, old and new.

In its four-star review, The Guardian called the film "expansive in its attitudes" and at times "quietly revolutionary," while BBC News said it was "likely to set a trend for more diverse storytelling in the country." As Pakistan's submission to the "Best Foreign Language Film" category for this year's Academy Awards, the film did not become a final round contender (no Pakistani entry has yet won the category). Nonetheless, watching it remains an intimate encounter with first-rate acting, observant cinematography, and a faraway world. If it was up to me, Cake would be required viewing here in America, where we so rarely hear about Pakistan unless the words nukes or Taliban are nearby. But I'm biased.

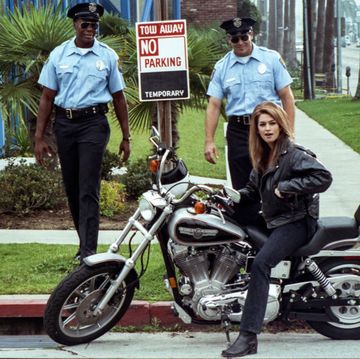

Often (too often), it takes some kind of personal connection to unlock our interest in another country's nuances. For me, one of the film's stars, Adnan Malik, 39, was that connection. He came to the U.S. to attend Vassar College back in 1998 and, afterwards, lived in Brooklyn for a couple years. Even though I went to another school then landed on the West Coast, we wound up in the same tight-knit, cross-coastal family of friends. While visiting Los Angeles just before his return to Pakistan, I remember Adnan rejecting our pleas for him to stay, saying his country needed people like him — and his firm sense of greater purpose struck me. Since then, Adnan's intermittent trips to L.A. and Facebook feed have kept his friends in the U.S. aware of the exciting trajectory of his career — from directing Pakistani music videos and a documentary, to becoming the face of a fashion campaign, hosting an awards show, and acting in this new breakthrough film.

Adnan says he took the role of Romeo — the Jamali family's soft-spoken, live-in nurse and the eldest daughter's love interest — largely because of the character's dissimilarity to the brash leading men that usually populate Pakistani and Indian films. He believes that the subjects we watch on our screens affect our cultures profoundly, and he thought a character like Romeo, who stands shoulder to shoulder with women, could have a positive impact on his country, where beliefs about women's rights vary radically. Pakistan is a place where a woman was elected prime minister in 1988, and where, in the rural Swat Valley, Malala Yousafzai was shot in 2012 because she advocated for the education of girls. I talked with Adnan about toxic masculinity and #MeToo in Pakistan, and about breaking the rules with Cake.

Sarah Fuss Kessler: What did you think of the role the first time you read the screenplay?

Adnan Malik: I actually passed on the role at first, because I thought it wasn't strong enough. Then I realized how important it is for men to be allies to women right now. Movies that have a woman protagonist are almost unheard of in Pakistan in recent years. And I loved Romeo's value system. He is a 21st century rewrite for how men are represented in cinema and television in the Subcontinent. Male characters here are often loud and brash. They're aggressive. They will chase the girl and get her at all costs. Romeo is sensitive, intuitive, gentle — a man who can take no for an answer. He also works for the Jamali household as a nurse, so he's part of a lower class than their oldest daughter Zareen, who is his love interest. You don't see these characters in major roles in Pakistani film.

SFK: Can you talk about some specific ways that toxic masculinity is a serious issue in Pakistan?

AM: Pakistan is a country of 200 million people, so it's hard to speak generally. There is a huge class divide and urban-rural divide. In cities women work. But overall, Pakistan has a patriarchal culture. Traditionally, women stay at home, and men go to work. Big companies have come into Pakistan in recent years, and getting a job at a bank or a multinational is a dream for many people. And what that does is create intense pressure to work in a country that is overpopulated and under resourced. When a society is hyper-masculine, men have to succeed and make all the money, and all the pressures of that builds. At the same time, the men never develop an emotional language where they can really express themselves, and it leads to toxic masculinity. I think it contributes to the objectification of women, and not knowing where your boundaries are — and frustration, and testosterone.

SFK: Where were your ideas around gender equality shaped?

AM: My values were shaped growing up in Pakistan with a strong, working mother and an older sister, who was a moral compass for me. My mother worked as much as my dad, and we had working staff. The maid who raised me was another mother figure with a really strong personality, and she was very no-nonsense with aggressive males.

SFK: The character Zareen is a part of the 98 percent Muslim majority and belongs to a higher class than Romeo, who is also Christian. Their love affair confronts class and religious divides in Pakistan. Are you seeing couples in your life breaking down these barriers?

AM: One of my friends — who's half Catholic and half Zoroastrian — just married another friend, who's Muslim. So it is happening, but there's that class divide. There is a small percentage of people who are wealthy, who are urbane, who are well traveled, who have maybe lived or studied abroad, have perhaps a different value system than other people here. Otherwise, there's still a lot of conservatism about how religion is approached here, so you're not seeing a lot of interfaith marriages across the board.

SFK: Has #MeToo had an impact in Pakistan?

AM: There is a lot of conversation around #MeToo, people who write about it, and there is heightened awareness in media circles. India had a lot of big #MeToo moments, which brought it closer to home. I think it has made men a little more cautious about where their boundaries are, but we haven't had a big watershed moment that's affected anyone's career. There was a big #MeToo case here, where a top female musician (Meesha Shafi) accused a male rock star (Ali Zafar) of harassment, but there wasn't any big resolution.

SFK: What made it possible to make a film as different as Cake now? Was it #MeToo? Was it India's massive 2012 protests against the gang rape of Jyoti Singh? Was it Malala?

AM: Progress for women and minorities seems to be a global phenomenon right now. It's all around us. It's the internet and people knowing what's going on everywhere around the world. It's partly #MeToo. Malala is actually a very divisive figure in Pakistan, unfortunately. Again, it's hard to speak generally, but many urban people support her, while most others think she is a traitor who sold out to Western interests by giving them dirt on her country. Right now we're experiencing a huge backlash against liberalism, in ways you could relate to what has happened in the United States. However, I think as a species we're still moving towards this progress. Pakistan has had women in powerful positions in society, including the first female prime minister in the Subcontinent, so a film like Cake is not coming out of nowhere. Back in the day, we used to have movies with female protagonists, like Miss Singapore and Miss Bangkok. These were action films with women leads who used to kick men's asses. My documentary about the '80s conservative religious shut down of Pakistan's film industry, The Forgotten Song, was used to change government policy to open the industry back up about 10 years ago.

SFK: The BBC speculated that Cake could set a trend for more diverse storytelling in Pakistan. Has it?

AM: Yes! The first movies coming out of Pakistan's new film industry were Bollywood copies. People are just now starting to come out and tell diverse stories. Since Cake did it and did well, there are already another couple films coming out, like Baaji [Sister], about a fading film actress and her ingenue, which also has female leads.

SFK: When will the U.S. get to see Cake and will there be subtitles?

AM: It will be coming to a streaming platform soon. Urdu is Pakistan's national language, but English is also recognized as an official language here. The characters speak a combination that we call "Minglish," but there are subtitles. We hope the trailer will hold you over until the release.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Get Shondaland directly in your inbox: SUBSCRIBE TODAY