T Bone Burnett Interview: Art Can Save Us

On his experimental new release, The Invisible Light: Spells, the legendary producer and musician uses creative truths to break through our current dystopia. In other news, he’s hoping to revolutionize the course of music commerce.

by Jeff Tamarkin

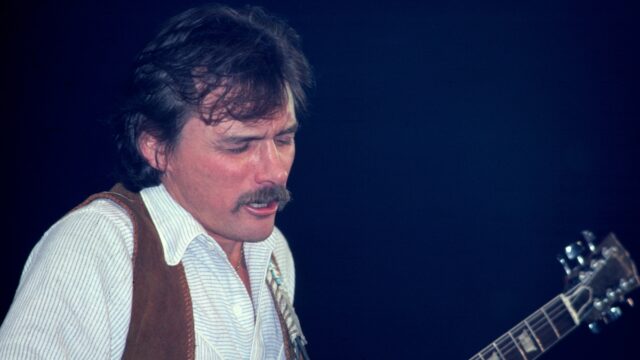

The veteran musician, songwriter and producer T Bone Burnett is best known for his work on projects that fall under the banners of rock, Americana and roots music, including two Burnett productions that won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year — the 2000 soundtrack O Brother, Where Art Thou? and the first meetup between Robert Plant and Alison Krauss, 2007’s Raising Sand.

But over the past half-century he’s answered different, more explorative musical callings as well. A case in point is his most recent release, The Invisible Light: Spells, the second volume in a trilogy that began three years ago with The Invisible Light: Acoustic Space. Both find Burnett, his longtime keyboard collaborator Keefus Ciancia and drummer Jay Bellerose incorporating electronics, samples and global rhythms.

The lyrical concept of The Invisible Light: Spells justifies the avant-garde approach, and the resultant pastiche resembles nothing else with which Burnett has been associated. In short, he’s on a mission.

“It’s my philosophy that if we, as a species, are going to be saved, it’s the artists who are going to do it,” he says. “I think every other part of life has been so compromised that the only ones that can speak truthfully are artists. The religious people are compromised. The politicians are compromised. The scientists are held in disregard. All of our institutions are being discredited. I think it’s up to us, the artists, to say the things that you can’t say in polite society.

“We’re working in a small, esoteric area,” Burnett continues, owning up to his new music’s experimental nature. “It’s about artists working in complete autonomy.”

We recently spoke with the Texas-rooted musician, born Joseph Henry Burnett in 1948, about the meaning and makings of The Invisible Light: Spells. We also delved into another recent audio project that he and his old friend Bob Dylan hope will spark nothing less than a reconsideration of the very relationship between music, technology and commerce.

What does the title The Invisible Light signify to you?

“The invisible light” is a phrase from T. S. Eliot’s “Choruses from ‘The Rock.’” He uses the term as a way of describing transcendence, or God. None of us has any idea who or what is behind all of this. It’s an incredible mystery, and there are a lot of people right now giving easy answers to this incredible mystery, and they’re doing all of us a disservice. It’s clear that we need to break out of this frame that we’re in of mass culture; artists need to break into the freedom of just telling the unvarnished truth.

The phrase could also refer to darkness, though. When you think about a black hole in space, it sucks in all of the nearby light.

The thing I’m looking at is all darkness, for certain. But hopefully we’re illuminating it. What you’re saying is very true. “Invisible light” is the same as darkness.

It doesn’t sound like dark music. I actually find it very bright and happy-sounding.

[laughs] Good! As these songs progress, they get more and more hopeful, or positive, or something. I believe, going back to the idea of artists, it’s up to the artist to imagine a better future, because we’re being programmed with dystopias all day and all night long. All the media and all the news channels, everything is describing life in dystopian terms at this point. As the trilogy progresses, we move more and more towards imagining a better future.

What roles do Keefus and Jay play in the creation of this music?

We’re equal partners. We’re collaborators. I bring in some lyrics. Jay brings in some drums; he’s got an extraordinary collection of drums from the ’30s and ’40s, calfskin heads. They’re super analog. And then Keefus comes in with an extraordinary library of samples that he’s collected over the last 20 years, and a lot of broken old analog synthesizers. We just set up in a circle and start playing. There’s a certain cadence in a piece of writing that you start from; the words provoke a rhythm. It all grows out of the words and then we just play. It’s the most fun I’ve ever had.

Why is this volume subtitled “Spells”?

The idea of spells — and it’s why a lot of things said in the record are repeated — is that people are incredibly suggestible, and we have to guard ourselves against the power of suggestion.

You do use a lot of repetition in the lyrics. You might sing the same word or phrase five times in a row.

Yeah. I’m doing that because I’m talking about the way these ideas get implemented. But I would much rather implement the idea that [love requires more courage than hate] than implement the idea that all of our elections are stolen.

You did an interview with the New York Times to discuss Acoustic Space, and you said that the second volume was going to be more rocking, which it is, and the third edition will be “very, very jazz.” Is that still the plan for the final part?

[laughs] Yeah. The third group of songs so far is completely impressionistic. Jazz is one way of saying it. I don’t mean it like bebop or anything. I just mean it comes unglued.

The Invisible Light records don’t use much instrumentation, yet the tracks sound huge. Sometimes it’s enveloping. Was that part of your conception?

I had been making records with Jay and Keefus for many years, and when we would mix down the records, the other things would always come to the fore: the stringed instruments, the pianos, the basses and guitars. There was such an incredible depth of sound in what Keefus and Jay were doing, I thought, one of these days I’m just gonna make a record with the two of them and leave out all the other stuff. We started getting together to just play that way and we came up with about 30 songs really quickly.

How does Acoustic Space relate to Spells, thematically and musically?

Acoustic Space starts with the idea of “I’ve always been a man without a country,” and the rest of these songs are that man looking for the country. In Spells, the country he finds is programmed and conditioned. I’ve been studying conditioned responses and electronic programming since the 1960s, and all of the thinkers that I was interested in in those days — Jacques Ellul, Marshall McLuhan, Neil Postman — all the dystopias that they were talking about as possibilities have come true. Way worse. I mean, the dystopia that we’re living in today is so much worse than the worst dystopias of my youth, of Nineteen Eighty-Four by George Orwell or Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World. We’re in a much more observed, surveilled society than they even dreamed of.

A lot of the reviews of the first album said that it was a major departure for you. Do you feel the Invisible Light records are outliers, or are they consistent with your previous work?

They’re certainly consistent thematically. My primary theme has been self-deception, which I’m expert at, by the way [laughs]. In some ways, it is not a departure at all, but I guess leaving out the guitars and the basses and the pianos is a departure. But the intent of it is, I think very much, in keeping with what I’ve been doing. I wanted to do something that I hadn’t done before.

There’s a line in the song “I’m Starting a New Life Today” that goes, “The ticking of the clock incessant, but it’s all happening at once.” What’s happening all at once?

All of it; everything’s happening at once. We call time time, because in our little solar system, the pattern of our revolving around our sun is a year, Earth time, so to speak. But that’s a marker that only exists in that one place. There is no time, not really. It’s a way we’ve chosen to define our existence here.

In the album notes, Jay is credited with Action Mechanisms and Thrums, rather than just drums and percussion, and then for Keefus it says Pulse Timing Circuits. Your credit says Resonators. What’s up with that?

That’s Keefus. He’s a very interesting cat. That’s all that is. How should we be credited, Keefus? That’s what he wrote back.

You essentially broke through with Bob Dylan, playing guitar in his legendary Rolling Thunder Revue, and recently got together to produce him in a re-recording of “Blowin’ in the Wind.” The story is that the recording uses a special technology and the original disc will be auctioned off. There will be no copies made, so theoretically it will never be heard by anyone else unless the buyer chooses to share it. You’ve also said that your aim with this concept, called Ionic Original, is to “develop a music space in the fine arts market.” Can you elaborate on all of this?

Recording artists have had the value of what we do determined for us under shorter-term technologies of mass production and distribution by organizations, government, broadcasters, distributors and others, but we’ve not had a way to find the value of an individual work of art, ever. Recorded music has always existed in the age of mechanical reproduction. Ionic Original discs provide artists with the ability to work at full autonomy on the best-sounding medium in an archival form, and through doing that, create a one-of-one piece. These Ionic Originals literally can’t be mass-produced. We can make one, we can make 10, we can make a hundred, but we can’t make a million or a billion or a hundred billion, or whatever the scale is now of consumerism.

The best-sounding [recording] medium, without a doubt, is an acetate; it’s the pinnacle of sound. [Recorded] sound started with smoke on paper; that was the first recording of the human voice. Then in the 1890s or so, there was the first recording on a wax cylinder; Johannes Brahms recorded some pieces on a wax cylinder in 1889. Starting there, it led up to a peak, in the early 1950s, of audio tape and vinyl, which were still the two best-sounding mass-produced media we have. But the source of all the vinyl was an acetate, and every musician I’ve ever worked with will tell you, when you put a master tape onto an acetate, it sounds better than the master tape. When you listen to the acetate and you listen to the vinyl copy, the acetate sounds better than the vinyl copy, by many steps, because the acetate is the source of all the vinyl copies. You make one acetate, and then you copy it, you silver-plate it and you make an impression of it. And then it goes through about five stages before it turns into a vinyl record.

We [Burnett and his collaborators in a venture called NeoFidelity, Inc.] went back and looked at what scientific advances could apply to analog sound. We looked at what is the best-sounding medium, and we said immediately the acetate. And we said, what can we do to protect the acetate? Realizing that heat melted it, we looked into what NASA was using to protect parts of the space station from the direct heat of the sun. It’s also the same technology that Apple uses on their iPhones, what they call Gorilla Glass, to keep the glass strong. We found a formula that could actually make the acetate not melt, that could future-proof the acetate. We’ve played them thousands of times, and they actually clean up as they go along. There are times when pops, or a click or a tick or something, will develop, but as you play it, it cleans it out. It keeps cleaning it. We have ones that we’ve played a thousand times that are dead quiet; there’s no surface noise. People who have heard it have said it really is like Bob’s sitting five feet from you.

Bob was into the concept?

Well, he dreamed it up years ago, so yeah. We’ve been talking about it for many years. What we aim to do is create one-of-one copies that are not for mass distribution, they’re for history. They’re gonna last longer and sound better, and because we’re selling them for a lot of money, they’re gonna be taken care of.

Why “Blowin’ in the Wind”?

It’s a beautiful, epic song. It’s a version he did 60 years after having written it, after having gone through all of the life that we’ve all been through for the last 60 years. The reading of it is deep; it’s profound.