Comparing 1998's "Psycho" Remake With Hitchcock's 1960 Original

Why Should I Care?

Hitchcock's 1960s broke the genre and changed the way that audiences looked at the psychological horror genre. It was also the film that sealed Hitchcock's reputation as a master filmmaker and director.

The 1998 big Hollywood attempt at a shot-for-shot remake is a rare enough thing to happen to any film. Because the 1998 remake is an attempt to copy the original source material, it serves as an excellent sounding board to compare themes, methods, and styles not just of the directors but of the gigantic gulf of 38 years of filmmaking. A slight alteration makes us not just ask why something has been altered but why the original was the way it was.

I will dissect the two films according to five different sections listed below:

- Differences in Camera Perspective Changing the placement of the camera changes the film, even in a "shot for shot" remake.

- Detail Manipulation Sometimes, the smallest details and alterations of those details in scenes give an insight into a director's intent.

- Character Alteration Norman Bates is presented in two very distinct ways in the two versions of the story.

- Plot Hole Closure Van Sant tries to close some of the minor errors in Hitchcock's film.

- Shifts of Overall Tone The inclusion of a montage changes the tone of the films.

- What Has Changed in 38 Years? How much of what's changed is due to the directors, and how much is due to the time between the two versions?

The relevant still shots from each film are included in each section, with any relevant footnotes being placed at the bottom of each section, separated by a dividing line.

By the Money ...

| Hitchcock's Original | Gus Van Sant's Remake | |

|---|---|---|

Year | 1960 | 1998 |

Budget | $806,947 | $60,000,000 |

Gross Income | $50,000,000 (estimated) | $37,141,130 |

Can the Remake Tell Us Anything?

Gus Van Sant's 1998 remake of Alfred Hitchcock's 1960 Psycho is a curious artifact for any Hitchcock aficionado. Critical reviews have largely denigrated[1] Van Sant's shot-by-shot retelling of Hitchcock's most iconic and famous film, but are they missing the point? It may seem natural to view the new version as an attempt to outdo the brooding genius of Hitchcock, but more thought is needed before dismissing an imitation as inevitably derivative. Van Sant’s reshooting of Psycho comparatively reveals the distinctions that made Hitchcock an effective filmmaker through both shooting style and detailed manipulation in the development of characters, plot, and overall tone.

_______

[1] The inference that critics are less supportive of Van Sant's version are drawn from the relatively low ratings given on IMDB (4.6 of 10) and Rotten Tomatoes (3.7 of 10) when compared to the original: IMDB (8.6 of 10) and Rotten Tomatoes (9.7 of 10).

Differences In Camera Perspective

Van Sant’s Psycho takes a different stance in shooting style. Van Sant’s Psycho is not an entirely “pure” shot-by-shot remake of the original. In addition to the creation and editing of a handful of scenes[1], several original scenes are altered by having original camera positions. The effect is subtle but useful in understanding the way that Hitchcock’s original functions through its use of camera perspective.

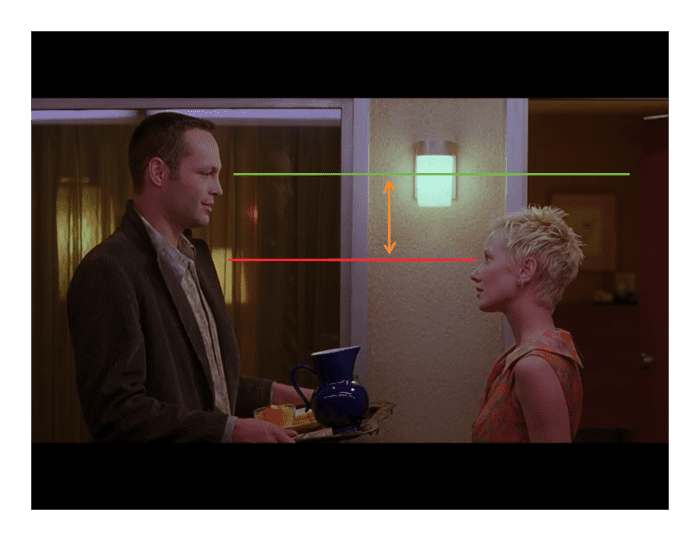

Van Sant’s alterations become the most significant immediately before and during the scene where Marion eats dinner with Norman in the hotel office parlor.[2] In the handful of shots where the characters of Marion and Norman converse outside of her open room door, there is one divergent but crucial change of shot.

When Leigh suggests that they eat in her room, she takes a step back and gestures as an invitation. Perkins consequently steps forward before hesitantly stepping back and asking her to join him in the hotel office instead. Within this original shot, Perkins’ half-step forward and then back are from a medium side-shot continuous from the previous dialogue (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Leigh and Perkins in the medium shot where almost all of their verbal exchange in this scene occurs

Psycho (1960)

Figure 2: Notice the comparable height difference between Vaughn and Heche. Notice also how everything seems to feel closer in Van Sant’s shot when compared to the one above.

Psycho (1998)

Recommended

Van Sant chooses to jump to a closer shot of Vaughn from the front, where his face is more visible (Figure 3), before having him step back (Figure 4) and cutting to the next shot. The change is significant for several reasons, and the effects it has are rooted in the ways that an audience might perceive the characters.

One of the draws of Norman’s character for audiences is his sympathetic appeal which relies on the audience being sutured into his perspective for an instant within one shot in the scene. The next shot is of Marion’s character from Norman’s perspective. Altering the scene to include a shot of Vaughn from Heche’s perspective right before switching to his perspective naturally diminishes the amount of an audience’s suturing into his character. When Vaughn steps forward, the audience doesn’t see him stepping toward Heche as in the original, but toward the screen and themselves.[3] Van Sant inadvertently places us within two sutures very rapidly and so cancels out their effect for one character or the other. This element alone reminds one of the effectiveness with which Hitchcock used the technique of suturing to manipulate the audience's emotions.[4]

Another effect of this shot change is the shift of focus from Perkins’ overall body movement in the original to primarily Vaughn’s facial expressions as they step forward into light and then back into symbolic shadow. This arises again in the next scene.

The dinner in the parlor scene is designed to tell Norman’s background story. The scene focuses heavily on exploring his personal dilemmas and establishing him as a sympathetic individual. One can only realize how passively Hitchcock accomplishes this when observing Van Sants’ remake.

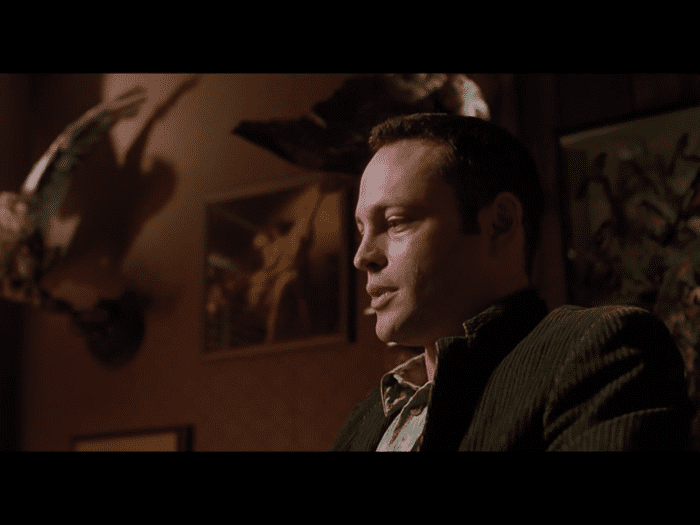

Hitchcock consistently shot Perkins from exactly the same angle so as to frame the swooping owl in the background with a deep depth of field (Figure 5). Perkins’ clasped hands are also placed so that they are just fully visible where they rest on top of his lap. Van Sant’s shot composition by contrast cuts off Vaughn’s hands when they are on his lap, uses a shallow depth of field, and drifts so that the owl goes from being distinguishable (Figure 6) to almost cropped out (Figure 7). Hitchcock makes it possible for the audience to focus their attention on details in the background of the scene and so passively enables the development of Norman’s character. Van Sant, by contrast, seeks to focus the audience’s attention exclusively on Vaughn’s face and upper body movements, drawing focus more actively on the actor himself.

Figure 5: Notice the deep focus into the background, which allows the viewer to absorb detail.

Psycho (1960)

Figure 6: Notice the sharpened focus on Vaughn at the expense of clarity in the background. This technique forces the audience’s attention of the subject.

Psycho (1998)

Figure 7: Notice how the freehand camerawork has caused the owl to become almost entirely cropped out of the shot later in this scene.

Psycho (1998)

Aside from changing the visual focus of the scene, Van Sant also changes the climax of the scene through his shot technique. Van Sant pans around Vaughn to come for a closer shot on his line, “Understand, I don’t hate her, I hate what she’s become. I hate the illness,” (Figure 8). In Hitchcocks original direction he jump cuts to a slightly closer perspective and has Perkins suddenly lean forward to make the shot a closeup just before he responds to Leigh’s line of, “Can’t you put her someplace.” The alteration makes Vaughn seem more assertive in making excuses for his mother whereas the more passive Perkin’s only reactes to the allegation that his mother should be institutionalized. When the traditionally climactic line does occur Vaughn can only slightly shift himself forward since he is already close to the camera. Van Sant’s alterations within the scene structure draw attention to the beats of the scene that Hitchcock focused on: particularly the passive nature of Norman.

Figure 8: Notice how tightly this shot focuses in on Vaughn’s face as he leans in at the cost of the background. The shot is much more invasive.

Psycho (1998)

_______

[1] Two of the most noticeable examples of heavily altered scenes are principally: (1) The scene of therapist who diagnoses Norman at the end of the film is shortened. (2) The final shot of the car being pulled from the swamp is extended with an extended shot on a crane that pulls up to show the landscape.

[2] Due to the possible confusion that could occur when referring to two different sets of actors playing the same set of characters, this paper will refer to the characters by their character names when talking about both sets of actors and the respective actors when referring to a specific version.

[3] It is very possible that Van Sant chose to shoot it this way because of Vaughn’s considerable height advantage over Heche (Perkins and Leigh were even) which contributes to the audiences perception of him as larger and potentially more dominant (Figure 2). One of Hitchcocks strategies throughout the original seems to have been to portray Perkins as diminutive, heightening the surprise when we discover he is the killer. Vaughn’s size puts him at a disadvantage so Van Sant is forced to compensate.

[4] In this case the overall objective of Hitchcock’s suture into Norman is to make the revelation that he is the killer even more jarring for the audience.

Detail Manipulation

After considering the ways that Van Sant can manipulate Hitchcock’s original picture through changes of camera perspective, the only other touches of influence are in small details that can affect overarching themes that recur throughout the original film.[1] Besides choosing actors, Van Sant was faced with decisions such as: which decorations to place in the parlor or which lines of dialogue to add[2] or exclude. These minute elements become crucial as the only means of divergent expression and commentary on the original.

The list of changes that Van Sant makes can be broken down into three categories based on the kind of thematic commentary they make: character alteration[3], plot closure, and shifts of overall tone. With each change the audience has the opportunity to ask why Hitchcock chose to present things as they are in the original.

_______

[1] Because Van Sant’s script was in many ways already written for him in the form of most shot directions and dialogue, there is only a small margin where the director can take creative initiative. Because the creative margin is so small, the smallest changes of details become important statements.