Abstract

According to recent studies, social media are settings where adolescents construct their identities while engaging in social interactions. In digital spaces, adolescents can interact with, display, and receive feedback about themselves, contributing to the development of a clear and integrated sense of self. This paper reviews the available empirical evidence and discusses four overarching themes related to identity construction in social media: self-presentation (attempting to control images of self to others), social comparison (compare themselves with others, especially evaluating the self), role model (media figures that are social references for behavior), and online audience (friends, peers, unknow/know referents with whom users may interact online). Moreover, it proposes a new contextual perspective on identity development on social media. Informed by research on these themes that social media features allow adolescents to perform self-presentations, offering the opportunity to express interests, ideas, and beliefs about themselves (identification and role exploration). The image presented on social media exposes them to feedback, online audiences, and social comparison with peers or social models. Audiences have an impact on how adolescents think about themselves (self-concept validation). Role models can facilitate the learning of behaviors through imitation and identification (exploration and commitment). Thus, the digital world provides a context for the development of adolescents’ personal identity. This proposal aims to contribute to the construction of future theories on identity in social media and advance this area of research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence is an important stage for identity development (Branje et al., 2021), a lifelong process that is influenced by settings, people, and social context. Erikson (1968) defines personal identity such as extent to which a person has adopted clear and consistent goals, beliefs, and values. Marcia (1980) describes the formation of identity as a process that can involve different statuses of development based on the amount of exploration (experimentation with different values, beliefs, or goals, questioning and weighting different identity options) and commitment (personal interest in those values, beliefs, or goals, engaging in significant activities) that the adolescent experiences or has experienced. The statuses of development are: (1) diffusion: in this status adolescents have not taken an active role in exploring different alternatives or committing to a specific identity domain; (2) moratorium: adolescents are actively exploring multiple alternatives, but they have not yet made any commitment; (3) foreclosure: adolescents have made a commitment without exploring it; and (4) achievement: after a period of active exploration, adolescents have committed to a specific identity domain (Marcia, 1980).

Researchers have recently broadened the two core processes of exploration and commitment into several developmental trajectories and models. The three-factor model (Crocetti, 2017; Crocetti et al., 2008; Crocetti & Meeus, 2015) proposes an identity explanation comprising three structural processes: commitment (choices made by individuals), in-depth exploration (reflection, seeking information about their commitments), and reconsideration of commitment (individuals compare their commitments with other options). Similar to Erikson’s proposal (identity vs. identity confusion), this model assumes that there are two opposing forces in the dynamics of identity construction: (1) commitment and in-depth exploration, and (2) reconsideration of commitment. Considering that the identity process is dynamic (unlike the sequential model proposed by Marcia, 1980), this model includes a dual-cycle process in which adolescents form, evaluate, and revise their identities. Adolescents in the identity formation period consider various alternatives (exploration process), maintain, and reinforce their chosen commitments (maintenance stage), or revise their decisions in a dynamic cycle (Crocetti, 2017; Crocetti et al., 2008; Crocetti & Meeus, 2015). In summary, personal identity refers to a subjective sense of self in diverse situations and times (distinctiveness and uniqueness) where adolescents explore and experiment with who wants to be, roles in adulthood, and their place in society (Branje et al., 2021).

According to Erikson`s (1968) theoretical models, in this article identity is understood as being constructed at the intersection of individual personality, self-conceptFootnote 1, interpersonal relations, and context (e.g., historical, social). At present, a relevant context for exploring and building identity in adolescents is social media and online activities (Raiziene et al., 2022). Adolescents are the most active group of social media users, especially through internet connections on their mobile phones. Adolescents use social media to express themselves, generate links and bonds with peers, and with social online referents, such as influencers, YouTubers, or Instagrammer (online audience). Recent studies have suggested that social media is a scenario of identity construction in which adolescents socialize (Lajnef, 2023; Meier & Johnson, 2022; Shankleman et al., 2021;Valkenburg, 2022). In digital spaces, adolescents can interact, display, and receive feedback about themselves, immediately contributing to the formation of their self-concept and exploration of their identity (Cingel et al., 2022; Shankleman et al., 2021).

Given the importance of the psychosocial task of identity, there has been a great amount of theoretical and empirical attention within psychology (for a review, see Branje et al., 2021). Nevertheless, they have placed little emphasis on digital context and its influence on identity development. In the last decade, the number of publications on social media and adolescents has increased considerably (for a review, see Davis et al., 2020), although the focus has been on the influence on well-being and negative consequences (e.g., problematic social media use, depression symptoms, risky behaviors) rather than on identity (Shankleman et al., 2021). This study addressed the influence of social media and online activities on identity formation during adolescence. Four central themes were analyzed in accordance with recent literature (Davis et al., 2020; Hollenbaugh, 2021; Meier & Johnson, 2022; Shankleman et al., 2021): self-presentation, social media audience, social comparison, and the role of models in an online context. This paper presents the findings thematically and includes a contextual perspective relating to social media use and identity formation. This perspective can be used to understand identity formation on social media as well as to guide future research.

Self-presentation on social media

Self-presentation is a behavior that attempts to transmit information about oneself or an image of oneself to other people, is activated by the evaluative presence of other people (Baumeister & Hutton, 1987), and plays a relevant role in identity development (Yang et al., 2018).

Self-presentation concerns how individuals control the image they portray to others, and social media has provided new contexts for selective self-presentation (representation of the personal image that individuals want others to perceive, common in selfies, and online profiles). Moreover, social media offers adolescents the opportunity to have multiple social interactions that broaden their perceptions and assessments they make about themselves, contributing to the construction of their self-concept (one’s overall view of oneself), given that the perceptions of the individual about themselves are based on their experiences with others and their own attributions of their own behavior (Meier & Johnson, 2022; Schreurs & Vandenbosch, 2021).

Research suggests that the relationship between self-presentation on social media and identity development is dynamic. Adolescents engage in identity exploration, and social media facilitates this process (e.g., through images, videos, and text), given that their self-presentation shows an image specifically for these media, often positively biased (de Lenne et al., 2020). The audience and characteristics of social media are central to self-presentation (and self-concept) because adolescents can craft and edit their images with more possibilities than offline interactions, and they can vary some aspects of themselves depending on the audience to which their messages are addressed (Hollenbaugh, 2021). By presenting themselves online, adolescents also regulate their impressions of themselves intentionally, usually to obtain the approval of others (management or handling of impressions) and test their self-concept for different audiences (Hollenbaugh, 2021; Meier & Johnson, 2022).

Adolescents act intentionally to regulate their impressions of themselves on social media to shape an attractive image and obtain approval from other users and followers (e.g., peers, friends). Social media self-presentation allows selective because them can edit their profile to a self-selected audience (Hollenbaugh, 2021). Nevertheless, social media also allows for expressing in a way more true or authentic self because adolescents can edit before posting to show a mood state or a thought about themselves (Shankleman et al., 2021). Hollenbaugh (2021) suggest «the effectiveness of self-presentation may be used as feedback to influence future impression management» (p. 84). Common types of self-presentation related to impression management include ingratiation and self-promotion. Ingratiation is the most frequent and aims to present a pleasant image of the self and a likable image on social media. For example, being friendly, funny, or saying positive things to others. Self-promotion includes highlighting skills, talents, competencies, and knowledge. For example, individuals are knowledgeable and skilled in sports, music, etc. Adolescents use these types of self-presentation and strive to create a positive image of themselves on social media (positivity bias) because they have a strong tendency to compare themselves with their peers and need peer acceptance (Schreurs & Vandenbosch, 2021), which is essential in the construction of identity.

Self-presentation is a transactional process that includes reflections on an individual’s identity and possible selves, as well as the audience and social context (Schlenker, 2003). Additionally, audience feedback about self-presentation on social media contributes to shaping self-concept and identity through multiple social interactions (Hollenbaugh, 2021; Meier & Johnson, 2022).

Online social media audience

The formation of identity and shaping of beliefs (self-concept), values, and behaviors can be influenced by social interactions with others as an audience (Schlenker, 2003). On social media, the audience (e.g., friends and followers) allows adolescents to connect with other people who are experiencing the same process (Shankleman et al., 2021).

Adolescents prioritize an ideal or desired identity image in the digital context (related to social desirability and the need for acceptance). Moreover, social media offer many opportunities to curate and present one’s identity to a wider audience. Therefore, users craft their profile thinking about who will see them, and they are conscious of the audience on social media (Marwick & Boyd, 2011). This audience can be real (friends, peers, family), proximal (an unknown referent or referents with whom social users may have offline interactions), or distal (an unknown referent or referents with whom they interact in their imagination). (Marwick & boyd, 2011).

Peer feedback (real audience) on social media is very important for adolescents’ identity. In early adolescence, there is an increase focus on the self (Elkind, 1967), and adolescents are highly sensitive to peer feedback. Social media permits the adjustment and optimization of online profiles (self-presentation) to elicit positive feedback, usually through comments and likes (Koutamanis et al., 2015). This feedback is more public, persistent, and visible to others (online audiences); therefore, negative feedback can influence self-esteem and the subjective evaluation of one’s worth as a person (Koutamanis et al., 2015). Instead, positive peer feedback can strengthen self-esteem, validate self-concept, and provide a sense of acceptance (Cingel & Krcmar, 2014; Peters et al., 2021).

Adolescents try to imagine the audiences’ perspective on their online profiles and posts and «act toward, react to, and thereby reinforce, a perceived Imaginary Audience»(Cingel & Krcmar, 2014, p.156). An imaginary audience is the belief that others are thinking and judging you all time, that you are at the center of others’ attention (admiring or critical), and this process is heightened during adolescence (Elkind, 1967). In the construction of identity, the imaginary audience allows, on the one hand, to express one’s identity and, on the other, it relates to the need to belong, mainly to those who are not linked to the closest social ties, such as the family (Lapsley et al., 1989).

To understand how adolescents present their identity online and interact with each other through social media, an imaginary audience is a useful lens. Adolescents use impression-management strategies to determine their post and comment audiences, using content-based (what to post/comment on and how to post/comment) or network-based (tailoring or limiting access to their posts) strategies (Ranzini & Hoek, 2017). Intensified self-consciousness due to an imaginary audience becomes a broad online audience on social media, and users can feel surveillance and constantly observed (Ranzini & Hoek, 2017). This imaginary online audience makes adolescents overemphasize their positive traits (positive bias on self-presentation) and more frequently post selfies on social media (de Lenne et al., 2020; Ranzini & Hoek, 2017). However, social media audiences also play a role in adolescents’ self-expression, and these spectators can produce an empowering feeling regarding their self-concept (Shankleman et al., 2021).

Imaginary audiences have also been related to risky online behaviors (e.g., sexting, and friending strangers online), mainly adding users based on a profile picture to increase followers and, consequently, the audience (Popovac & Hadlington, 2020). In addition, the number of followers and likes on social media could intensify the imaginary audience: «a larger online audience may serve to increase social status among peers but also likely contributes further to the Imaginary Audience ideation itself» (Popovac & Hadlington, 2020, p. 286). In this manner, the feeling of having an online audience can generate expectations in adolescents and influence their behavior. Online audiences can impact behavior by stimulating different outcomes: warning (when new behaviors are favored by online audiences) and chilling effects, when behaviors are restricted by the online audiences (Marder et al., 2016; Lavertu et al., 2020). The impact of online audiences on offline behavior can be either warming or chilling, depending on the individual’s goal. Therefore, the extended chilling effect of social media is «the constraining of behavior in reality (i.e., offline) as a consequence of the perceived expectation these online audiences hold» (Lavertu et al., 2020, p.1); for example, people would avoid smoking in the fear that a photo would be posted on social media (Marder et al., 2016). In accordance with Marder et al. (2016), «people could respond in a ‘chilling’ manner for a number of reasons, including fear of external sanctions and social disapproval, regardless of whether or not that threat of sanction is real or not» (p.582). Moreover, Lavertu et al. (2020) proposed that public self-awareness (based on imaginary and real audiences online) can also be a positive self-referent (warning effect), for an individual’s behavior (e.g. participating in prosocial behavior offline).

Social comparison on social media

Social comparison is relevant in building adolescent identity because it has been suggested as a significant process of self-knowledge and a means of self-improvement or self-evaluation (Lajnef, 2023). In other words, «social comparison are often motivated by individuals’ desire to evaluate, improve, or enhance the self» (Noon et al., 2023, p. 292). Social comparison is a natural process of self-evaluation, in which individuals tend to choose those who are perceived as similar to themselves as targets for comparison (Festinger, 1954). This tendency uses other people as sources of information to determine how we behave, feel, or think relative to others (Festinger, 1954). The social comparison process relies on the choice of comparison target (upward: superior other versus downward: inferior other) and the outcomes of the comparison (assimilation versus contrast). Social comparison can be upward when others are considered better or in better condition, or downward when the people we compare ourselves to are seen as worse (Festinger, 1954). In assimilation, the self-evaluation of the comparer shifts in favor of the comparison target, becoming more positive after upward comparison and more negative after downward comparison. Contrast is the process of a comparer’s self-evaluation shifting away from the target, which can become more negative when compared upward, and more positive when compared downward (Verduyn et al., 2020). Therefore, comparisons between the self and others can have judgmental, affective, and behavioral consequences.

Adolescents compare themselves with their peers and are concerned about building a personal identity, so they frequently use social media to present themselves in a favorable or positive way. In the digital world, social comparison is a frequent process (especially upward social comparisons) because these networks allow for an idealized image of others, share more self-enhancing information about themselves, and explain more successes than failures (Verduyn et al., 2020).

Social media posts increase the discrepancy between the actual self and the ideal self, eliciting a greater number of comparisons to others in an upward manner and highlighting dissimilarity (Midgley et al., 2021). Comparisons on social media often include identity domains such as peer relationships and physical appearance. For example, social media users choose the most attractive photos and usually edit them using filters (positivity bias) to represent their idealized self (Schreurs & Vandenbosch, 2021). In addition, users of social media also expect «likes» of the images published, which is often related to an adolescent’s search for social approval (Feltman & Szymansky, 2018). Social media places a great deal of importance on the exchange of popular pictures (with the most «likes») and receiving comments, and pictures that are retouched with filters to make them more attractive to their observers, normally representing ideals of beauty that are shared socially, such as being thin and in shape (Baker et al., 2019; Fardouly et al., 2018; Feltman & Szymanski, 2018).

Cultural standards of beauty refer to acknowledgement of the predominant social standards of physical attractiveness, appearance, and weight, which are supported by significant individual beliefs and objectives (de Lenne et al., 2020; Feltman & Szymanski, 2018). In internalization, individuals incorporate the ideals of beauty or other media ideals (e.g., academic or professional success) established by society into their own beliefs (de Lenne et al., 2020; Feltman & Szymanski, 2018), although not to the same degree. In this process, individuals cognitively adopt as personal, a socially defined ideal (de Lenne et al., 2020; Feltman & Szymanski, 2018). In Western society, these standards of beauty are associated with the desire to be thin, fashionable, and fit (healthy and muscular). (Feltman & Szymanski, 2018).

Social networks usually offer unrealistic skinny or muscular models or celebrities with an ideal body image that is virtually unattainable and may result in a negative self–image (de Lenne et al., 2020; Vandenbosch et al., 2022). This is particularly relevant in adolescence, when body changes are most evident and require greater effort to be incorporated into the construction of identity. The presence of unrealistic models on social networks, which respond to cultural ideals of beauty (being fit, thin, fashionable), usually represents an ideal self-model for most adolescents (Fardouly et al., 2018). This content offers more opportunities for internalization by applying an observer´s perspective to their own appearance or other media ideals (de Lenne et al., 2020; Vandenbosch et al., 2022). Thus, posts on social media also provide an idealized view of reality in other domains, such as professional, social, or romantic lives. These media permits obtaining information about others in their profiles, frequently more popular, or with more follows. This process increases the social needs acceptance of adolescents and the social comparison and internalization of media ideals (de Lenne et al., 2020). This emphasis on a positive version of oneself online can lead to a comparison effect (especially upward comparisons) which can impair well-being. For example, it can reduce self-esteem (Cingel et al., 2022; Midgley et al., 2021).

The most active users of social networks often have more upward social comparison (Feltman & Szymanski, 2018). Nevertheless, the current review indicates that the use of social media (passive or active) has positive effects (Meier & Johnson, 2022; Shankleman et al., 2021; Valkenburg, 2022). For example, an investigation suggests positive consequences (e.g., inspiration and pride) in other self-presentation types, such as leisure, work, health, or travel, especially when comparisons focus on assimilation or contrast with the target. Upward assimilation (more similarities with the target) and downward contrast (fewer differences from the target) improve well-being. Conversely, downward assimilation and upward contrast are expected to decrease well-being (Meier & Johnson, 2022).

Social comparison promotes self-knowledge, self-improvement, and self-evaluation in adolescence (Lajnef, 2023). However, social comparison (upward social comparison) with peers on issues related to ideal body image and physical appearance, produces more negative effects on well-being (Cingel et al., 2022; Midgley et al., 2021). In other domains, such as leisure or health, the consequences of this social comparison (upward assimilation and downward contrast) can be positive (Meier & Johnson, 2022).

Roles models on social media: imitation and identification

Meaningful relationships and social connections in adolescents’ face-to-face interactions are extended to social media and provide a referent or role model of behavior (e.g. influencers) to develop their sense of identity (Berger et al., 2022). Social media presents a different type of role model: celebrities, influencers and micro-influencers, who are famous because of their large followers (influencers) and personal branding strategies (micro-influencers). These influencers are frequently identified by a specific audience, create content that centers around lifestyle topics such as food, travel, or beauty, share significant parts of their lives on their social media platforms, and engage with their followers to maintain their status (Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023).

Media figures are social references for different identity domains that offer inspiration for self-development, self-esteem, and the exploration of different roles: vocational, gender, and sexual orientation (Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023). According to social cognitive theory (Bandura, 2001), social norms are learned (imitate) and accepted by observing the behavior of role models (e.g., peers or influencers) on social networks, principally when they are rewarded (de Lenne et al., 2020). Because adolescence is a stage characterized by the need to belong to a social group or be accepted by peers, these relationships with media figures can facilitate the learning of certain behaviors through modeling or imitation, which can have a positive or negative influence (Bandura, 2001). For example, «adoption of healthy attitudes and behaviors modeled or promoted by the media figures (+)»; «engagement in risky behaviors such as teen alcohol use modeled by media figures (−)» (Hoffner & Bond, 2022, p.2).

Social media referents are considered identification models because they share similar features with adolescents and young people who follow them; also offers certain attributes that adolescents would like or aspire to have as their ideal self, which represents an identity challenge between the “teens ‘simultaneous need for «mimic» and «differentiation»” (Lajnef, 2023, p. 5). Consequently, the internalization process of these norms and ideal media (e.g., popular, with large numbers of followers and likes) contributes to the identification of these referents (e.g., influencers) in social networks (Lajnef, 2023).

In scientific literature, this identification process is usually explained by parasocial relationships. This process refers to the perception of closeness or intimacy that a viewer or listener has with characters - fictional or presenters - of mass media (Hoffner & Bond, 2022). Repeated social media interactions between audiences and influencers create parasocial relationships. These relationships «are socio-emotional connections that people develop with media figures such as celebrities or fictional characters» (Hoffner & Bond, 2022, p.1). Among the characteristics that favor this type of relationship are the affinity, authenticity, trust, familiarity, or attractiveness of those media referents (Hoffner & Bond, 2022) and the processes of identification and ideal or wishful identification (Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023). In the identification, influencers are viewed as someone who shares traits similar to those of adolescents are following them, which are related to the actual self. In ideal identification, influencers have some attributes that the person would like to have or aspire to have, related to the ideal self (Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023). The development of parasocial relationships between adolescents and media figures is a process derived from the search for new roles (exploration stage in identity building) of behavior beyond the family environment and allows them to meet the social needs of attachment and friendship (Gleason et al., 2017; Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023).

Adolescents establish this type of relationship with those who consider their peers, role models, or media referents such as influencers or celebrities (Eyal et al., 2020; Gleason et al., 2017). Social media for their immediacy and the possibility of interaction helps to create and develop parasocial relationships between adolescents and media figures (Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023). Moreover, in this context, users can observe life - and, in many cases, the intimacy - of people who, in normal circumstances, could never (Hoffner & Bond, 2022). In adolescents, parasocial interaction can occur more frequently because they experience changes in their relationships with peers and family (Gleason et al., 2017), which covers the social needs of attachment, similarity with those who consider their peers, in addition to being associated with the perception of their social world (Eyal et al., 2020). Social media provide a scenario for the development of such relationships in adolescents. It offers anonymous people and celebrities a platform where they can develop these relationships with their followers by exposing (self-disclosure) their «private» life, that increases the socio-emotional connections (Hoffner & Bond, 2022).

By adopting or imitating behaviors that they attribute to the «traditional» influencer (professionals in using social media’s different channels, careful personal brand with a wider audience), users can develop a parasocial relationship. In imitation, users aspire to act in a manner that is similar to a fictional character; for example, they copy their style (clothes, music) because they are characterized by attractive qualities. Moreover, imagination about media reference evokes and promotes the interaction (Gleason et al., 2017; Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023). Thus, the users comments with other fans or discussion groups exclusively dedicated to the figure of the influencer (fanclubs), or through other meetings, such as the interaction imagined with the influencer through images and fanfiction (fictional works written by fans from literary works, television series, film, or other media) or through an attempt to contact the same through comments on their profile, labels, or other calls for attention (Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023). Indeed, in the identity development of adolescents, these types of parasocial relationships allow the exploration of interests that may be common to those of influencers or micro-influencers (due to the process of identification with the media figure and imitation of their behavior). It can also facilitate self-expression, especially in identity domains such as gender and race, which often have limitations in their expression or social recognition in certain cultures (Gleason et al., 2017; Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023).

On social media such as YouTube, TikTok, or Instagram, it is very difficult to establish a two-way relationship between the media referent (e.g. influencers) and his/her followers because of the large number of interactions (publications, comments, «like») that exist. Therefore, parasocial relationships with these influencers are based on virtual relationships, considered «real» by viewers though one-sided (Hoffner & Bond, 2022). Consequently, the «followers» in social media (especially with celebrities or influencers) are a unilateral concept because these social referents have many followers that make the interaction extremely difficult (Hoffner & Bond, 2022). Influencers also may adopt communication practices with followers (posting personal videos or photos) to promotes closeness and reciprocity, although sometimes it can be a strategy to increase the audience (Riles & Adams, 2021). However, in the case of micro-influencers, followers are more likely to perceive greater reciprocity (back-and-forth interaction), which can blur the perception of unilaterality in the relationship. Reciprocity contributes to establishing a relationship between users and micro-influencers, given that the followers find commonalities and response to their messages. Thus, when a follower interacts with a media figure, the relationship can change from parasocial to interpersonal (Riles & Adams, 2021). Both macro and micro influencers on social media represent a social model of behavior, especially in the adolescent stage (Berger et al., 2022). The processes of interaction with these media figures favor the identification and imitation of behaviors related to the identity process (Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023). Adolescents explore different ways of being through models that can be considered as their peers, in which they are reflected (like a mirror), and in which they can share similar experiences and interact in relation to their doubts or identity experiences (Gleason et al., 2017; Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023).

Towards a contextual perspective about identity development on social media

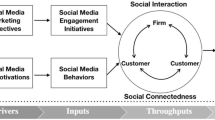

The main challenge in adolescence is the formation of an identity. According to Erickson’s (1968) classic theory proposal, there are two important processes at this stage: identification with tasks and skills and exploration of social roles and experiences. Identity is constantly evolving and constructed based on changes in intrapersonal (individual’s inner perceptions or characteristics), interpersonal (relationships and bonds with others), and social domains (culture, political context, school, social media); and the current context, adolescents have a digital world in which to develop these processes (see Fig. 1). A contextual-ecological perspective considers adolescence development as a unitary system with attention to the complex interactions between these domains: intrapersonal, interpersonal, and social. «From this ecological perspective, youth are seen as subject to contextual forces ranging from the proximal influences that operate in their everyday activity settings, to increasingly distal (and abstract) contextual forces» (McHale et al., 2009, p. 1190).

On the one hand, self-expression (public and private images of themselves) on social media allows them to practice their self-presentation skills, show who they are, and receive feedback from their audiences (de Lenne et al., 2020; Hollenbaugh, 2021). Social media provides many opportunities to curate (e.g., craft profile) one’s identity to a wider audience (real, proximal, or distal), and the feedback (positive or negative) can strengthen or diminish self-esteem, validate or no self-concept, and provide a sense of acceptance or rejection by peers (Koutamanis et al., 2015; Peters et al., 2021). Imaginary online audiences can overemphasize positive traits in adolescents and strongly believe that others (audiences on social media) are judging all the time (Elking, 1967; Ranzini & Hoek, 2017). On the other hand, social media allows them to experiment with different ways of being, expose their interests, know what others do, identify with certain behaviors, reject others, explore ways of communicating, and show themselves to others (Shankleman et al., 2021).

As Marcia (1980) pointed out, a certain level of exploration and commitment is required to develop a stable identity. Different statuses of identity development (diffusion, moratorium, foreclosure, and achievement), based on the degree of exploration and commitment, are expressed in digital spaces (Cingel et al., 2022; Raiziene et al., 2022; Shankleman et al., 2021). On social media, adolescents can try various identity alternatives before deciding which values, beliefs, or goals to pursue (self-representation and self-concept construction). It also allows adolescents to establish identity options, such as groups to which they belong, cooperate, or participate in social activism, among others. In this way, the process of identity construction in adolescents is influenced by the processes of individual-society integration, in which they can share or modify the values or identity options important to them (Erikson, 1968). Therefore, it is important to recognize the interplay between the social, interpersonal, and psychological aspects of identity development in the digital context. In this sense, role models on social media (peers or influencers) are a social reference for these behaviors (Hoffner & Bond, 2022). Peers or influencers on social media are referents of behavior to develop their sense of identity in domains such as vocational, gender, or sexual orientation (Berger et al., 2022).

Social comparison on social media influences self-knowledge, self-improvement, and self-evaluation in identity building (Noon et al., 2023; Lajnef, 2023). An indicator that identity develops properly is the presence of self-concept clarity, a coherent and consistent description of oneself (Campbell, 1990), which in social networks involves exploring and experimenting with different ways of being until achieving this integrated self-concept. Negative self-evaluation on social media (mainly upward social comparison) can influence identity development, diminish self-esteem, reduce commitment, confuse exploration, and increase uncertainty (Noon et al., 2023).

Social media also demonstrate the dynamic process of identity construction as proposed by Crocetti et al. (2008). In this relational context, adolescents explore alternatives identities and form commitments based on their interests and values. In addition, it allows these commitments to be strengthened, explored in depth, or dynamically reconsidered (Crocetti & Meeus, 2015).

These theories explain identity building in adolescence based mainly on the process or dynamics of exploration and commitment of adolescents. However, it is also important to know where adolescents explore their identity and the context (person-in-context) in which they are developing (McHale et al., 2009). Adolescents can connect to social media many hours a day, which is an accessible way to explore and build their identity in this context. The referents of identity construction in the past have been family, friends, and educational centers and currently, social media provides an important context that have effects on development of adolescents’ identity (see Table 1).

Discussions

Theoretical models of the construction of the adolescent’s identity have focused their attention on individual processes in which identity alternatives are explored and commitments are made, without major emphasis on how decisions can be influenced by the context and vice versa. In this study, a contextual perspective focused on the role of social media allows the identification of the processes of mutual influence (media and individuals) and their effects on the construction of identity during adolescence. Self-presentation, online audience, social comparison, and the role model (social media domains) have positive and negative consequences on the psychosocial development of adolescents.

Classic questions about identity construction, such as who am I? What do I want to do? relevant during adolescence’s biological, social, and psychological changes are now expressed in a digital scenario. For example, recent research explains that connections on social media support or hinder the relationships that adolescents create with their peers or friends (Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Shankleman et al., 2021). In addition, feedback about themselves, which they usually receive from people close to them, comes from an online audience without limit (Popovac & Hadlington, 2020; Ranzini & Hoek, 2017). Online audience produce an empowering feeling of self-presentation (Shankleman et al., 2021), negative consequences (e.g. surveillance) and risky behaviors (Popovac & Hadlington, 2020). Consequently, the role of social media audiences in adolescent identity process requires further evidence.

Psychosocial changes during adolescence, such as autonomy, need to belong, peer acceptance, self-esteem, and self-concept, interact with a particular digital context that has important implications for identity development. Social networks offer the opportunity to express interests, ideas, and beliefs about themselves (self-concept), with possibility of constant reinvention and the availability of digital tools to manage or handle the impression they make on others (Meier & Johnson, 2022; Schreurs & Vandenbosch, 2021). Also, social media allows the expression of an adolescent’s distinctiveness (e.g. expressing who you are) to differentiate from others (Shankleman et al., 2021), as well as the identification or imitation of social referents (Hoffner & Bond, 2022; Lajnef, 2023).

Social comparison with peers or social referents (e.g., YouTubers, TikTokers) can be a risk factor for adolescents who are more vulnerable, although they can foster a self-positive image. Thus, they can also be a way to acquire healthier habits and enhance self-esteem and well-being (Cingel et al., 2022; Lajnef, 2023; Vandenbosch et al., 2022). Moreover, parasocial relationships on social media have a positive impact on well-being domains such as social connection and coping (Hoffner & Bond, 2022). Therefore, it is necessary to expand research on the effects of social media references (e.g. influencers) on the identity of adolescents.

Social comparison in social networks is a relevant and frequent process because of the characteristics of these media, in which more importance is given to idealized publications about themselves (Verduyn et al., 2020). Moreover, it increases dissimilarity with others and the internalization of media ideals (de Lenne et al., 2020; Midgley et al., 2021). However, they also offer the opportunity to obtain information from other profiles that facilitate self-verification (Swann, 1983) and to test the expression of identity for a variety of audiences (Hollenbaugh, 2021; Meier & Johnson, 2022).

Social media enhances a sense of connection with others and increases peer relationships that are more extensive than they are realized in the «real» world. The exchange that occurs in online communities can facilitate the dynamics of identity construction, offering opportunities to explore, maintain, or reconsider their commitments (Branje et al., 2021; Crocetti, 2017; Crocetti et al., 2008; Noon et al., 2023). Digital space transforms and amplifies this process, often too quickly for adolescents to comprehend. Nevertheless, this online communication process represents for many teenagers a space for shared listening (including comments and responding to online publications) and the expression of the different challenges of identity construction (Lajnef, 2023; Shankleman et al., 2021). Further research is needed on how social media influences the dynamics of identity construction, especially how it relates to the processes of commitment, in-depth exploration, and the maintenance or reconsideration of those commitments (Branje et al., 2021; Crocetti, 2017; Crocetti et al., 2008; Noon et al., 2023). It would also be interesting to explore how they perceive the continuity of their identity over time (e.g., comparing old posts/images on social networks vs. the current one) and how this can support a sense of identity affirmation (Shankleman et al., 2021).

The significance and prominence of social media in adolescents results from the process of identity building that occurs during these development period (self-expression, friendships, or peer acceptance).The digital world can serve as a platform for adolescents to choose who they are and what activities they prefer without the social pressure of their closest or family environment, as previously mentioned. In turn, it can become a space with difficulties and risks associated with this stage of development, which requires a commitment to reflection, accompaniment, and action on the part of those in the social context of adolescents (e.g. parents).

Data availability

There are no new data associated with this article.

Notes

References

Baker, N., Ferszt, G., & Breines, J. (2019). A qualitative study exploring female college students’ Instagram use and body image. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 22(4), 277–281. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0420

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory of mass communication. Media Psychology, 3, 265–299. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0303_03

Baumeister, R. F., & Hutton, D. G. (1987). Self-presentation theory: Self-construction and audience pleasing. In B. Mullen, & G. R. Goethals (Eds.), Theories of Group Behavior. Springer. Springer Series in Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4634-3_4

Berger, M. N., Taba, M., Marino, J. L., Lim, M. S. C., & Skinner, S. R. (2022). Social media use and health and well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(9), e38449. https://doi.org/10.2196/38449

Branje, S., de Moor, E., Spitzer, J., & Becht, A. (2021). Dynamics of identity development in adolescence: A decade in review. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 31(4), 908–927. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12678

Campbell, J. D. (1990). Self-esteem and clarity of the self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(3), 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.3.538

Cingel, D. & Krcmar, M. (2014). Understanding the experience of an imaginary audience in a social media environment implications for adolescent development. Journal of Media Psychology, 26(4), 155–160. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105/a000124

Cingel, D., Carter, M., & Krause, H. (2022). Social media and self-esteem. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101304

Crocetti, E. (2017). Identity formation in adolescence: The dynamic of forming and consolidating identity commitments. Child Development Perspectives, 11, 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12226

Crocetti, E., & Meeus, W. (2015). The identity statuses: Strengths of a person-centered approach. In K. C. McLean, M. Syed, K. C. McLean, & M. Syed (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of identity development (pp. 97–114). Oxford University Press.

Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., & Meeus, W. (2008). Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of a three-dimensional model. Journal of Adolescence, 31(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.09.002

Davis, K., Charmaraman, L., & Weinstein, E. (2020). Introduction to special issue: Adolescent and emerging adult development in an age of social media. Journal of Adolescent Research, 35(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558419886392

de Lenne, O., Vandenbosch, L., Eggermont, E., Karsay, K., & Trekels, J. (2020). Picture-perfect lives on social media: A cross-national study on the role of media ideals in adolescent well-being. Media Psychology, 23(1), 52–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2018.1554494

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38, 1025–1034. https://doi.org/10.2307/1127100

Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. W.W. Norton & Company.

Eyal, K., Te’eni-Harari, T., & Katz, K. (2020). A content analysis of teen-favored celebrities’ posts on social networking sites: Implications for parasocial relationships and fame-valuation. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2020-2-7

Fardouly, J., Willburger, B., & Vartanian, L. (2018). Instagram use and young women’s body image concerns and self-objectification: Testing mediational pathways. New Media and Society, 20(4), 1380–1395. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817694499

Feltman, C., & Szymanski, D. (2018). Instagram use and self-objectification: The roles of internalization, comparison, appearance commentary, and feminism. Sex Roles, 78, 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0796-1

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

Gleason, T., Theran, S., & Newberg, E. (2017). Parasocial interactions and relationships in early adolescence. Frontier Psychology, 8, 255. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00255

Harter, S. (1999). The construction of the self. Guilford Press.

Hoffner, C., & Bond, B. (2022). Parasocial relationships, social media, & well-being. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101306. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101306

Hollenbaugh, E. (2021). Self-presentation in social media: Review and research opportunities. Review of Communication Research, 9, 80–98. https://doi.org/10.12840/ISSN.2255-4165.027

Koutamanis, M., Vossen, H., & Valkenburg, P. (2015). Adolescents’ comments in social media: Why do adolescents receive negative feedback and who is most at risk? Computers in Human Behavior, 53, 486–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.07.016

Lajnef, K. (2023). The effect of social media influencers’ on teenagers behavior: an empirical study using cognitive map technique. Current Psychology, January 31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04273-1

Lapsley, D., FitzGerald, D., Rice, K., & Jackson, S. (1989). Separation individuation and the ‘‘new look’’ at the imaginary audience and personal fable: A test of an integrative model. Journal of Adolescent Research, 4(4), 483–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/074355488944006

Lavertu, L., Marder, B., Erz, A., & Angell, R. (2020). The extended warming effect of social media: Examining whether the cognition of online audiences offline drives prosocial behavior in ‘real life’. Computers in Human Behavior, 110, 106389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106389

Marcia, J. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Adelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 159–187). Wiley.

Marder, B., Joinson, A., Shankar, A., & Houghton, D. (2016). The extended ‘chilling’ effect of Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 582–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.097

Marwick, A., & boyd (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444810365313

McHale, S., Dotterer, A., & Kim, J. (2009). An ecological perspective on the media and youth development. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(8), 1186–1203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764209331541

Meier, A., & Johnson, B. (2022). Social comparison and envy on social media: A critical review. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101302

Midgley, C., Thai, S., Lockwood, P., Kovacheff, C., & Page-Gould, E. (2021). When every day is a high school reunion: Social media comparisons and self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 121(2), 285–307. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000336

Noon, E. J., Vranken, I., & Schreurs, L. (2023). Age matters? The moderating effect of age on the longitudinal relationship between upward and downward comparisons on Instagram and identity processes during emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 11(2), 288–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968221098293

Peters, S., Van der Cruijsen, R., van der Aar, L., Spaans, J., Becht, A., & Crone, E. (2021). Social media use and the not-so-imaginary audience: Behavioral and neural mechanisms underlying the influence on self-concept. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 48, 100921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2021.100921

Popovac, M., & Hadlington, L. (2020). Exploring the role of egocentrism and fear of missing out on online risk behaviours among adolescents in South Africa. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 276–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1617171

Raiziene, S., Erentaite, R., Pakalniskiene, V., Grigutyte, N., & Crocetti, E. (2022). Identity formation patterns and online activities in adolescence. Identity, 22(2), 150–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2021.1960839

Ranzini, G., & Hoek, E. (2017). To you who (I think) are listening: Imaginary audience and impression management on Facebook. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.047

Riles, J., & Adams, K. (2021). Me, myself, and my mediated ties: Parasocial experiences as an ego-driven process. Media Psychology, 24(6), 792–813. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2020.1811124

Schlenker, B. (2003). Self-presentation. In M. R. Leary, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.), Handbook of self and identity (pp. 492–518). Guilford.

Schreurs, L., & Vandenbosch, L. (2021). Introducing the Social Media Literacy (SMILE) model with the case of the positivity bias on social media. Journal of Children and Media, 15(3), 320–3370. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2020.1809481

Shankleman, M., Hammond, L., & Jones, F. (2021). Adolescent social media use and well-being: A systematic review and thematic meta-synthesis. Adolescent Research Review, 6, 471–492. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-021-00154-5

Swann, W. B. Jr. (1983). Self-verification: Bringing social reality into harmony with the self. Social psychological perspectives on the self. In J. Suls, & A. G. Greenwald (Eds.), Psychological perspectives on the self (Vol. 2, pp. 33–66). Erlbaum.

Valkenburg, P. (2022). Social media use and well-being: What we know and what we need to know. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.006

Vandenbosch, L., Fardouly, J., & Tiggemann, M. (2022). Social media and body image: Recent trends and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.12.002

Verduyn, P., Gugushvili, N., Massar, K., Täht, K., & Kross, E. (2020). Social comparison on social networking sites. Current Opinion in Psychology, 36, 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.04.002

Yang, C., Holden, S. M., Carter, M. D. K., & Webb, J. (2018). Social media social comparison and identity distress at the college transition: A dual-path model. Journal of Adolescence, 69, 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.09.007

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author contributed to the conceptualization, writing-review & editing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

No data has been collected that requires approval from an ethics committee. This study does not involve human participants. It was not necessary to request informed consent.

Conflict of interest

The author report there are no competing interests to declare. The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez-Torres, V. Social media: a digital social mirror for identity development during adolescence. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05980-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05980-z