The road to Star Trek: The Motion Picture was a long one. Initially conceived by series creator Gene Roddenberry in 1969 following the cancellation of the original television series, it wasn’t until six years later that Paramount Pictures agreed to begin development on the project. But despite a revolving door of some top writers in science fiction pitching ideas, disagreements regarding the budget and Paramount’s desire for an epic blockbuster led to Roddenberry abandoning the project in favor of a new television show, tentatively named Star Trek: Phase II. Except when that fell apart too, Paramount had a big issue on their hands. Production had been set to begin in a matter of weeks, with a full cast and crew already hired and an entire season of sets and scripts under construction. There was no way Roddenberry could afford to let all that work go to waste, and as luck would have it, he had no intention to either.

The result was Star Trek: The Motion Picture, built from the ashes of Phase II that reused as many resources from its parent project as it could, most notably the script “In Thy Image” that had been intended as the show’s pilot episode (albeit one that got heavily rewritten when the jump to a feature film was made). With The Sound of Music and West Side Story director Robert Wise in the directing chair progress was finally being made, and despite several behind-the-scenes troubles that resulted in hourly script rewrites and special effects being worked on right to the final deadline, Star Trek finally hit the big screen in December 1979.

And the result was not what Paramount had been hoping for. While the film was a modest success at the box office, the film received a mixed response from critics with criticism directed at its slow pacing and lack of action. Roddenberry was forced out of creative control for the sequel, The Wrath of Khan, which placed a greater emphasis on action and received a much warmer response in turn, becoming the template future Star Trek films would follow. This also resulted in The Motion Picture feeling like a bizarre anomaly in its own franchise, with a tone in vast contrast to later entries. The slow pacing has led to fans dubbing it The Slow Motion Picture, and it is generally accepted that newbies should skip this one in favor of its more accessible sequels. But to do so would be doing a disservice to a film with more merit than its reputation suggests. The Motion Picture will not appeal to those who prefer films of a more reasonable length with an explosion or two thrown in for good measure, but for those looking for a more thoughtful and cerebral take on the science fiction genre, there is plenty to appreciate.

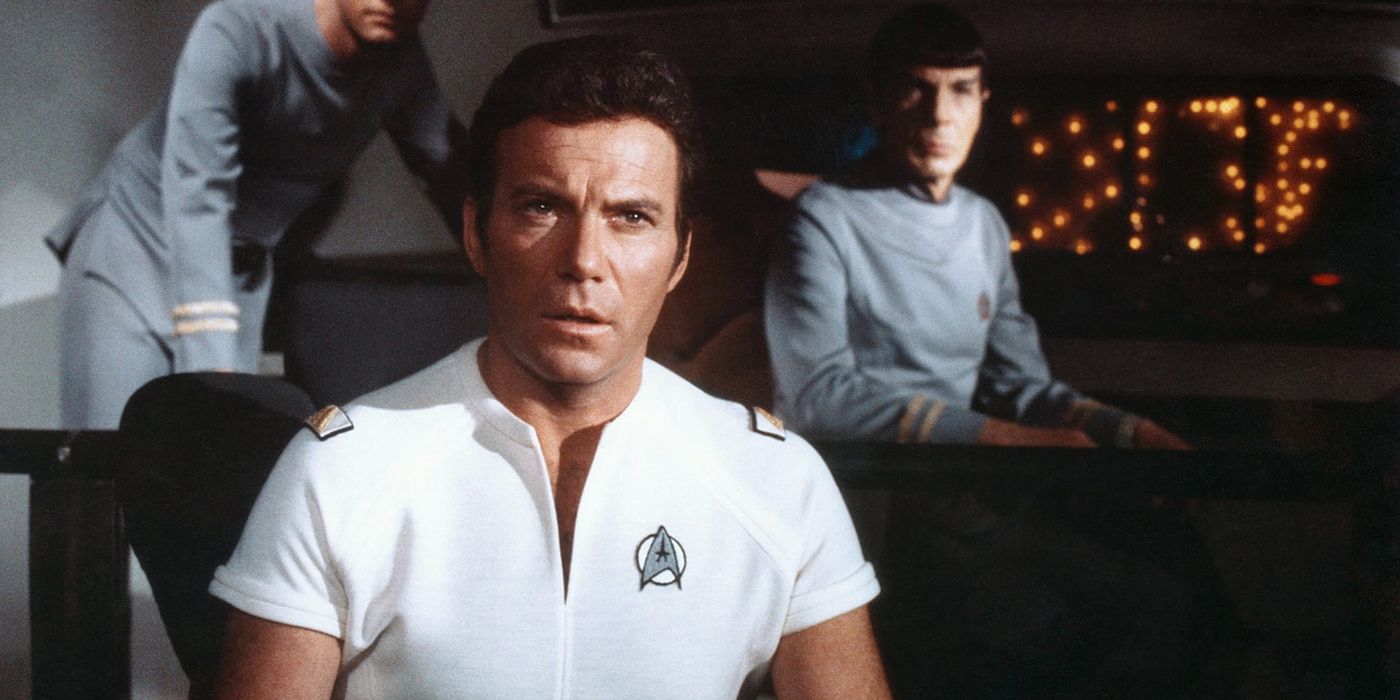

The film’s story, written by seemingly every writer in Hollywood but credited to just Harold Livingston, sees recently promoted Admiral James T. Kirk (William Shatner) taking command of the newly refurbished USS Enterprise as he investigates a mysterious cloud of energy known as V’Ger that destroys everything in its path, and which is currently on a collision course with Earth. And that’s basically it. The script feels like exactly what it is; an episode of a TV show that has been stretched to fit a feature film, and that does create some problems. The plot remains rather stationary throughout its runtime, lacking much in the way of exciting set pieces or even a clear villain that’s more than just a cloud, but Wise takes advantage of the minimalist plot to craft an experience like no other.

For one, nothing in the franchise’s sixty-year history captures the grandeur of space like this. While future films may have had larger stories when compared to the simplicity of this, none of them come close to the levels of splendor The Motion Picture imbues into every moment. The sequence of Kirk and the ship’s engineer Scotty (James Doohan) boarding the retrofitted Enterprise lasts six minutes, most of which consists of reaction shots of the two actors as they bask in the ship’s glory. To some it’s an overlong sequence that could be completed in a fraction of the time, but the excellent special effects and grandness of Jerry Goldsmith’s musical score combine to make it an utterly memorizing scene. Beauty for beauty’s sake, a concept that too few films embrace. This same sense of grandeur persists throughout the film, where even the most mundane of moments are presented with enough pomp and ceremony to fill a musical (the echoes of Wise’s previous work can clearly be felt). Space is the ultimate of grand concepts, and with many contemporary films (including some in the same franchise) barreling through entire galaxies in the blink of an eye like the characters are just casually driving down a country lane, it’s refreshing to see a film bask in the wonders of science fiction, where even the most distant of stars glow with the power of endless possibilities.

But the film’s methodical pace also allows for richer characterization than its successors. The friendly comradery between the crew of the Enterprise is gone here, replaced by a coldness that alienated fans of The Original Series, but it’s a decision that allows Wise to explore these characters in new but refreshing ways. Ten years have passed since audiences last saw these characters, and rather than picking things up like no time has passed, it genuinely feels like ten years of hardship have befallen them. Kirk is a far more vulnerable character than his television counterpart, with his unfamiliarity with the retrofitted Enterprise the source of much conflict with its new captain William Decker (Stephen Collins). He demotes Decker and takes command of the ship, partly due to his greater experience dealing with such events, but also for his own selfish desires to pilot a starship again after spending the last few years trapped in the offices of Starfleet Operations. It’s a decision that nearly destroys the ship when he activates warp speed, causing Kirk to gradually accept the importance of his crew rather than assuming his decisions will always be correct. It’s nothing revolutionary, but it develops his character beyond being just a standard hero archetype he often falls into, whilst also providing a standalone arc that ensures The Motion Picture feels like a complete feature rather than just another episode of a TV show. Shatner, while never the best of actors, does an admirable job playing a more reserved version of his signature character, and the result is his best performance in the role.

This richer characterization also extends to the film’s supporting cast. Chief medical officer Leonard McCoy (DeForest Kelley) is unhappy about being drafted back into action, only softening to the idea after Kirk tells him there’s a thing out there that he needs help dealing with (with McCoy’s response “why is any object we don’t understand always called a thing” being the film’s defining line). Even Spock (Leonard Nimoy), never the most excitable of characters, seems more emotionally distant than ever. When he first appears on the Enterprise there’s no grand entrance or reprise of classic Star Trek music as he reminisces with his old friends, he merely appears and resumes his work without even glancing at most of the crew. It’s as though, amongst the vast emptiness of space, everyone has lost their humanity, a feeling echoed by the clinical nature of the costumes and set design. But this is also a film where people strive to be better, where its idea of a dramatic sequence is not explosions and fighting but Kirk and McCoy desperately trying to get Spock to open up about his problems, so they can help him. Sparks of humanity are hard to come by, but when they do, they are cherished like they’re the most valuable thing in the universe. The budding romance between Decker and the ship’s navigator Ilia, while in any other film just a forced addition to widen mass-market appeal, becomes the cornerstone which the entire climax depends on. By the time the end credits roll Kirk and his crew have resumed their close friendship The Original Series thrived on. It took over two hours to get there, but the optimistic future Gene Roddenberry had envisioned is back, and it’s stronger than it has ever been.

The film’s special effects were one of the few elements to receive praise when it first released, and rightfully so, even if it wasn’t an easy process getting there. After the original special effects supervisors were fired following a full year of work that had yielded almost no usable footage, legendary visual effects maestro Douglas Trumbull was brought onboard. His work on 2001: A Space Odyssey and Close Encounters of the Third Kind had earned him an excellent reputation in Hollywood, giving him effectively an unlimited budget to complete years’ worth of effects in just nine months. Work continued right up to the eleventh hour, but Trumbull and his team managed it, and their work remains impressive to this day. The magic of the docking scene or the film’s famous light probe sequence wouldn’t be half as good without his work, and it took several years before the series again featured effects that replicated the brilliance of Trumbull’s work.

Perhaps the most impressive element of The Motion Picture is its villain, or lack thereof. V’Ger, the evil cloud that has been causing everyone such problems, is actually Voyager 6, a space probe programmed to gather knowledge from every corner of the universe, and also something that had been thought lost centuries ago. In reality, it gathered so much information that it achieved sentience, but in doing so became a being of pure logic that began to question its own existence. The reason for its journey to Earth isn’t to cause mindless destruction, it merely wants to question its creator about its place in the universe, with the havoc it is causing being an unintended consequence of its newfound sentience. It’s a remarkable change of pace when compared to the villains in virtually all other science fiction properties whose motivations can often be boiled down to just power, money, or revenge. Instead, The Motion Picture opts for a lonely machine than just wants a purpose in life, and our characters go about solving this methodically and thoughtfully without a trigger ever having to be pulled.

It’s a mindset that encompasses the entirety of The Motion Picture, a film that favors contemplation about the human soul in lengthy scenes full of subtle performances and cleverly written dialogue, rather than hurrying through the dull bits to get to the next action scene. Not that such films are inherently bad, of course. The Wrath of Khan placed a greater focus on action and proved to be a perfectly enjoyable summer blockbuster, but the unique approach of The Motion Picture makes it a film that is long overdue a revaluation.