This post contains spoilers for the movie 1917.

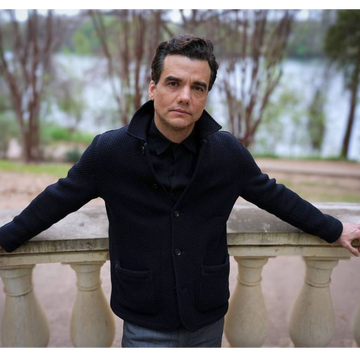

“When you stand up in No Man’s Land, you feel like you’re actually going to get shot in the head,” says Dean-Charles Chapman. He’s talking about filming Sam Mendes’s gripping—and now Academy Award Best Picture-nominated—1917, where he stars as Lance Corporal Blake, a young soldier tasked with the impossible during a pivotal moment in World War I. “Stepping on set for the first time, it felt so realistic. The trenches, the mud; it was so difficult to just even walk along. It’s such an uncomfortable feeling.”

It was emotional, he agrees, but not in that he suddenly identified with the brutal soldier experience, of now or of those who served in the Great War. Rather, it was the opposite. In wearing the wet, dank wool costumes, tripping through mud, and struggling to see through fog, he says he was humbled by just how easy he actually has it. “You’d get all of these little reality checks,” he explains, “seeing that this is nothing compared to what the men went through. We get to take the costumes off at the end of the day. They didn’t.”

Audiences and critics have also, though for different reasons, been consumed with the WWI epic, which is based on a combination of true stories. The mission Blake, alongside Lance Corporal Schofield (George McKay), are tasked with is shocking: an Allied battalion is about to walk into a German trap several miles ahead and they must be warned before dawn otherwise they all, including Blake’s brother, will be killed. With communications down, the two soldiers must travel by foot to deliver the orders in person and save 1,600 lives. And it gets a proper, and unique, treatment from director Sam Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins (Skyfall, No Country for Old Men). The entire 117 minutes feels like one continuous shot; the audience’s perspective never strays from the heroes who lead them across enemy territory.

Put simply: there's a lot more than just keeping the camera running to nail such a style. The crew spent six months rehearsing, says Chapman, in order to get such long takes. But much of the work had been done even prior to that: "Every location had to be exactly the correct length for the scene," Mendes explained to Vanity Fair last year. "We had to walk every step the characters would take long before we designed the sets and built them. I’ve never rehearsed a movie for as long, or in such detail."

The painstaking plotting showed, immediately, says Chapman. "They made sketches of No Man's Land and little mini models of the grounds," he recalls. "But with the first World War, there's really just a lot of black and white photographs. It's hard to wrap your head around [what it looked like]. It seems a little bit alien. But stepping on the set for the first time—I mean, any of the sets, the trenches, No Man's Land, even the countryside bits—it was so much detail. It was so realistic. You probably couldn't get closer to recreating the first World War, ever."

The ambitious approach is deserving of acclaim, but it was about more than landing a technical achievement, says Chapman. “It was to immerse people,” he explains. “And rather than just watch the film, actually experience the film; live in the film as you're watching it.” To say it works is an understatement, as the piece feels more like a ticking time bomb thriller than a classic war opus.

That the film’s leads, are—were—relative unknowns for the silver screen, worked on several levels. (Chapman’s largest credit, to date, is his turn as Tommen Baratheon on HBO’s Game of Thrones; MacKay, who plays Lance Corporal Schofield, appeared in the 2016 Viggo Mortensen vehicle Captain Fantastic.) “I think [the audience] would definitely be taken out of the story a little bit, or could have been, if you have Leonardo or Brad Pitt in there,” the actor, 22, agrees.

The casting also feels central to the film’s thesis: In the madness of brutal combat, young, otherwise anonymous individuals are asked every single day to complete tasks beyond our own imaginations in their scale of danger. Watching 1917, it’s almost impossible not to wonder, how many forgotten names does it take to save the world?

It’s undeniable that this will change Chapman’s young career, which is what makes his initial reaction to auditioning all the more amusing. “I just genuinely didn’t have the time,” he says with a slight laugh, recalling how he initially dismissed the opportunity. “[My agents] kept asking me to self-tape for it and I kept saying, ‘No, fuck it! It can’t I’m up to my eyeballs with, like, words and scripts and characters!” He was on set in Ireland for Here Are All the Young Men, an independent film due out later this year, but, as luck would have it, two months later when he’d wrapped production, Mendes and co. were still searching for the right fit for Lance Corporal Blake.

“Literally all I knew was the character name,” he says of how he went into his first read. “I knew that Sam Mendes was directing. I knew that it was called 1917—that was literally all I knew.” He didn’t know much more even when he accepted the part. “Even the second audition, they didn’t send me the full script," he recalls. "[What they sent me] was like four or five pages long.”

Chapman was, then, as surprised as audiences have been to learn Blake’s fate: After he and Schofield cross a haunting No Man’s Land, survive a harrowing walk through German bunkers, and begin their journey through enemy territory, a plane is shot out of the sky, crashing near their current location. It’s not one of their own, and as the flames tear through the pilot’s fatigues, Schofield suggests they put him out of his misery. They can’t, Blake begs; go get water, he yells. Before Schofield can fetch a bucket, the airman’s knife has already inflicted its mortal wound on Chapman’s storyline.

It’s a testament to Mendes’s remarkable writing what I wished in that moment, as my heart thudded against my chest in the theater: You shouldn’t have tried to save him. It wasn’t fair, and somehow that made it feel so much true. “It was honestly the best thing I had ever read,” says Chapman of the scene. “That was just so beautifully written. I actually shed a tear ... You know, if it’s a TV show, you don’t want to get killed off because you want to come back for the next season—you want the work—but here, it’s two hours long. And the best way to tell the story is with that happening.”

That's a feeling Chapman knows intimately, as his role as Tommen found its end in the finale of Game of Thrones' sixth season. As for that experience, Chapman is fairly succinct. "I'm so pleased and honored, really, to have been a part of something that's done really well. As an actor, it can be really hard to get a job or do things you actually really wanted to do in your career. And you never know what you're going to do next. Even now, I've got nothing lined up. [But] so far I've been pretty proud of the choices that I've made."

Perhaps the hardest part of watching that moment is seeing McKay-as-Schofield’s face fall when he realizes that he is, literally, now all on his own out here. When the operation began, Blake was the engine. He had to save his brother and, certainly compared to his partner-in-arms, he still felt like he could do something out here in this barren wasteland. That purpose transfers to Schofield when Blake dies. He has to get to Blake’s brother; he needs to write to Blake’s mother.

"His spirit really lives on throughout the rest of the film,” Chapman agrees. “It’s Blake that really keeps Schofield going until the end. I really just didn’t want to cock it up.”