THIS CONTENT IS BROUGHT TO YOU BY NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology - read more

Climate emissions from air travel is 50 per cent higher than official reports

A comprehensive study analysing nearly 40 million flights in 2019 reveals that global aviation emissions were 50 per cent higher than previously reported figures to the United Nations.

For the first time ever, researchers have used big data to calculate greenhouse gas emissions from air travel for 197 countries covered by an international treaty on climate change.

At 911 million tonnes, the total emissions from aviation are 50 per cent higher the 604 million tonnes reported to the United Nations for 2019.

When the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change treaty (UNFCCC) was signed, high-income countries were required to report their aviation-related emissions. However, 155 middle and lower income countries, including China and India, were not required to report these emissions, though they could choose to do so.

This is significant because the UNFCCC relies on these reports during negotiations on country-specific emissions cuts.

“Our work fills the reporting gaps, so that this can inform policy and hopefully improve future negotiations,” says Jan Klenner.

He is a researcher at NTNU’s Faculty of Engineering and the first author of the article that was recently published in Environmental Research Letters.

The research revealed that countries like China, which did not report its 2019 aviation emissions, ranked just behind the United States in terms of total aviation-related emissions.

“Now we have a much clearer picture of aviation emissions per country, including previously unreported emissions, which tells you something about how we can go about reducing them,” says Helene Muri, a research professor at NTNU. She was one of Klenner’s supervisors and a co-author of the paper.

Big surprises – or not

As might be expected, the United States leads in total aviation emissions from both international and domestic flights.

“When we looked at how emissions are distributed per capita, we could see that economic well-being leads to more aviation activity,” Klenner says.

This analysis also placed wealthy Norway, with a population of just 5.5 million people, in third place behind the US and Australia in domestic emissions per capita.

Klenner tested the model he developed for this analysis by using data from Norway, results of which he published in a 2022 paper.

Norway’s geography – a long, narrow country with lots of mountains and a sparsely populated northern area – might seem to explain the high numbers.

However, Klenner’s 2022 analysis revealed that 50 per cent of Norway’s domestic flights connect major cities like Oslo, Trondheim, Stavanger, Bergen, and Tromsø.

“The per person emissions in Norway were incredibly high. With this data set we can confirm that from a Norwegian perspective we have a lot of work to do, because we are third in the world when it comes to emissions per person from domestic emissions,” Muri says.

A role for big data

Anders Hammer Strømman, a professor at NTNU’s Industrial Ecology Programme and co-supervisor to Klenner, highlighted the significance of using big data to regulate climate emissions in their latest study.

“I think it very nicely illustrates the potential in this type of work, where we have previously relied on statistical offices and reporting loops that can take a year or more to get this kind of information. This model allows us to do instant emissions modeling – we can calculate the emissions from global aviation as it happens,” he says.

The model, called AviTeam, is the first to provide information for the 45 lesser-developed countries that have never reported their greenhouse gas emissions from aviation. According to Strømman, this model provides these countries with information that might be otherwise difficult or impossible for them to collect.

The capability to assess aviation emissions nearly in real-time also offers a valuable tool for the industry as it moves towards decarbonisation.

“In the transition where we’re talking about the introduction of new fuels and new technologies, this type of big data allows us to identify those types of corridors or operations where it makes sense to test those strategies first,” Strømman says.

Reference:

Klenner et al. Domestic and international aviation emission inventories for the UNFCCC parties, Environmental Research Letters, 2024. DOI: 10.1088/1748-9326/ad3a7d

More content from NTNU:

-

4×4 interval training is popular and controversial

-

Artificial intelligence makes smarter use of seaweed and kelp

-

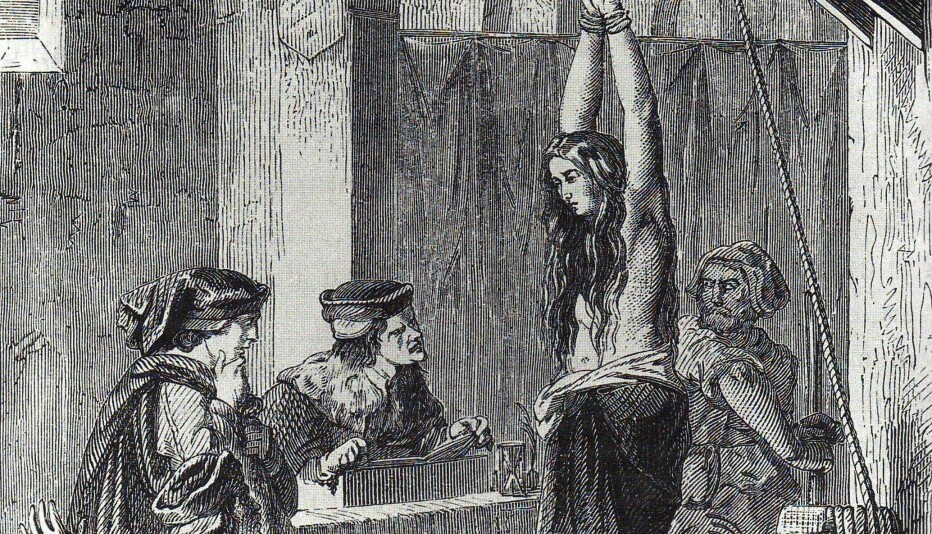

The end of witch trials did not stop religious persectuion of Norway's indigenous Sámi people

-

Researchers have found more than 16,000 chemicals in plastic

-

Can life at sea teach us to live in a more meaningful way?

-

Do you have an ear for languages? It may be related to how you perceive the rhythms