Why did Europe Go Haywire in 1848?

Blog by

First published: Sunday May 12th, 2024

Report this blog

First published: Sunday May 12th, 2024

Report this blog

+7

Quick Links

This blog shall provide an academic overview of the causes of the 1848 Revolutions in Europe. It is chiefly intended for college students due to the intricate information provided and the high level of vocabulary.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

Due to the blog's sheer length, a summary encapsulating the main points is included at the end.

Several annotations can be found throughout the blog elaborating on a particular concept or providing more information. These link to the Notes section.

For ease of learning, I have provided some hyperlinks to Encyclopedia Britannica or other relevant websites for certain specific terms.

Due to the blog's sheer length, a summary encapsulating the main points is included at the end.

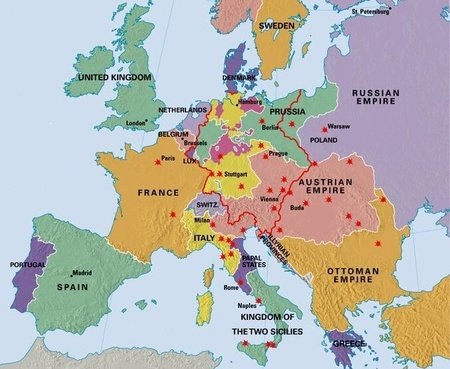

Map of Europe in 1848: the revolutions stretched from Ireland to Poland and the Romanian principalities, rendering them the most widespread in European history.

Overview

In January 1848, a gush of arrant censure to the stubborn status quo ensued from the sullen masses of Europe, unable to bear the burden of surviving solely by hope and a prayer against worsening socioeconomic woes any longer. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, monitoring the events of 1848 and 1849 with brisk alacrity, rejoiced at the perceived dawning of the long-awaited proletarian revolution; the exploited working classes would finally supplant the conservative monarchies’ suppression and emancipate themselves from authoritarian tyranny, securing the desired dictatorship of the proletariat [a]. [1] In The Communist Manifesto, they forewarn that ‘a spectre [was] haunting Europe—the spectre of communism’. [2]

Sure enough, the entire continent—from as far west as Ireland to the eastern limits of Poland and Moldavia and Wallachia [b], incorporating France, Denmark, most German and Italian states and the Austrian Empire—was balefully misted by revolts for one-and-a-half years. The conservative order crafted in the Congress of Vienna was in jeopardy; the stifled masses rose in such vigour and unanimity unrivalled by any demonstration since. Australian historian Christopher Clark asserts that ‘in the combination of intensity and geographical extent, the 1848 Revolutions were unique […] Neither the great French Revolution of 1789, nor the July Revolution of 1830, nor the Paris Commune of 1870 [1871], nor the Russian Revolutions of 1905 and 1917 sparked a comparable transcontinental cascade’.

The gush’s waves had dampened by the summer of 1849, but their ripples resounded throughout the rest of European history. The Fall of Communism in Eastern Europe certainly parallels with 1848 as one-hundred-fifty years later, member states of the Warsaw Pact collectively defied a common antagonist: the overbearing sovereignty of the Soviet Union.

The Industrial Revolution

The First Industrial Revolution, [c] commencing in 1760 and pinnacling in the early nineteenth century, altered European socioeconomic dynamics and culminated in widespread disgruntlement among the working masses. As capitalism flourished, the bourgeoisie consolidated their ascendancy over social milieus by promoting rapid urbanisation and industrialisation (i.e., the development of factories). [5] Industrial output surged—by two to three-and-a-half per cent annually from 1810 to 1830 [6]—and populations swelled disproportionately. The United Kingdom's tripled from six million to twenty-one million in the span of a century and cities consequently became oversaturated; the 1851 census indicated an unprecedented surpassing of urban residents over those rural. [7]

Malthusian catastrophes [d] (formulated by Thomas Robert Malthus) sprung up as agricultural production, growing at a linear rate, could not meet the populaces’ exponentially increasing demands; resource shortages became all too common. [8] Besides manufactured or harvested products being unavailable, they could scarcely be afforded at all due to the iron law of wages (coined by Ferdinand Lassalle). The bourgeoisie was reluctant to boost wages; in Great Britain, they only rose in annual increments of 0.3 per cent from 1760 to 1830 and the wealth gap between classes consequentially intensified. [9]

Overpopulation also led to excessive reliance on poor, primitive sewage systems, often were no more advanced than a few interconnected pipes directing waste to a river. Typhus and cholera epidemics infested most of the continent throughout the 1830s and 1840s. [10] The necessity of rudimentary sanitary reforms was blatant yet governments refrained from ameliorating living conditions; for instance, the first British legislation on this matter, the Public Health Act, only passed in 1848. By that time, hundreds of thousands of industrial workers had fallen victim to disease. [11] The Romantics [e] and Victorian writers bitingly captured the tenebrous mood of urban environments; in his poem “Did those feet in ancient time”, William Blake labelled factories ‘dark, satanic mills’. [12] French social reformer Victor Considérant did not reserve his criticism of nineteenth-century cities’ squalor either, labelling Paris ‘an immense workshop of putrefaction, where misery, pestilence and sickness work in concert’. [13]

The Bievre River in Paris before Baron Haussmann's renovation of the city [f] in the 1850s and 1860s: the city's industrialisation inflicted a massive burden on local sewage systems such that waste had to be dumped into the river, evincing the extreme squalor in mid-nineteenth-century Europe.

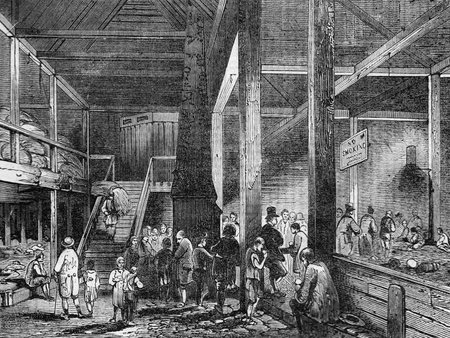

Famine

The Malthusian catastrophes were paired with an onslaught of famines in the latter half of the 1840s, more fittingly dubbed the “Hungry Forties”. They dawned in 1845, when a blight plagued just under half of the Irish potato harvest, relegating four million in the island to desperate starvation and poverty. [14] Lord Russell’s Whig administration, strictly bound to laissez-faire capitalism, [g] refused to actively intervene in providing benefits for the impoverished, instead directing this work to merchants and private charities. [15] As the rest of the continent quivered at the famine’s gravity, exacerbated by the meagre harvests of 1846 in France, [16] monarchs adopted a similar hands-off strategy, leaving their people at the mercy of the mercilessly rapacious bourgeoisie.

Humanitarian aid could not suffice; soup kitchens and workhouses were poorly managed and insufficiently equipped to deal with the unprecedented level of individuals taking up rations, [17] which was over fifty per cent in most of Ireland. [18] The bitter winter of 1846 to 1847 invariably aggravated matters, [19] and such nations as France and Prussia raised grain prices to unaffordable levels. [20] Many rural peasants either resorted to vagabondry or emigrated to a more provident environment; no country was afflicted by this social unrest as much as Ireland, which underwent a thirty per cent population decrease from 1841 to 1861. [21] Blogger Patrick Abbot notes that owing to the potato blight in the United Kingdom, ‘there is an endless list of contemporary reports of people starving or dying of disease’. [22] Adopting liberal free trade [h] policies could have alleviated these economic concerns by accepting food products from other nations. Yet, most governments remained fixated on protectionism, no less than Austria.

British urban refugees during the Great Famine of the late 1840s: many farming families became too impoverished to provide a living for themselves and therefore relied on private institutions for employment and accommodation.

Rise of Socialism

The first half of the nineteenth century oversaw the flourishing of socialist and syndicalist thinking in France, gradually permeating the continent. Whilst most of the proletariat was illiterate, most could certainly sympathise with socialist writers’ repudiation of the hardships characterising the First Industrial Revolution. Between 1780 and 1833, most labour took the form of heart-wrenching tasks such as coal mining and shipbuilding, [23] and materialistic competition between factories resulted in advanced machinery being implemented that the average worker could barely operate. [24]

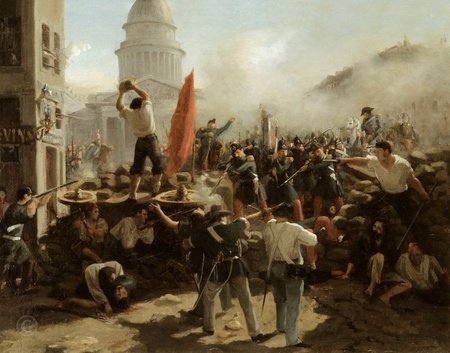

The gap between classes in terms of income disparity widened exaggeratingly as the proletariat was beneath the bourgeoisie’s heel. [25] “Class struggles” dominated industrial society, as famously declared in the first chapter of The Communist Manifesto: ‘The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles’ and that ‘the modern bourgeois society […] has but established new classes, new conditions of oppression, new forms of struggle in place of the old ones. [26] Pioneering social utopian thinker Charles Fourier encapsulated the proletariat’s poor conditions owing to the bourgeoisie’s repudiation of reform: ‘By reducing [the present condition of the domestic and salaried classes to…] slavery, civilisation, on the rebound, imposes chains upon those who seem to dominate. Thus, notables do not dare to amuse themselves openly at times when the people suffer from poverty’. [27]

Malaise and poverty adumbrated densely-packed cities and capitalism was perceived as the culprit. Laissez-faire economics—refusal to impose a minimum wage [28] or regulate corrupt industrial practices—and insistence on free trade rather than protectionism to incentivise the value of manufactured goods ensured the perpetual dominance of the bourgeoisie’s interests. French prime minister from 1847 to 1848 François Guizot defended the status quo and urged Parisian workers to persevere through their hardships, asserting the mantra “enrichissez-vous par le travail et par l’épargne” (“grow rich through work and savings”). [29] The proletariat was indeed working and saving… but not growing rich—if anything, devolving further into poverty.

The defence of government inaction throughout Europe did governments no favours as the price of wheat doubled from 1846 to 1847 in Paris and Berlin [30] and the cost of living far exceeded workers’ salaries. The flailing availability of resources lessened manufacturing production; by Okun’s Law, [i] this resulted in dipping employment rates. [31] In the years leading to 1848, such urban cities as Roubaix had sixty per cent unemployment and one-third of Paris was on social welfare. [32] As such, French socialist writer Louis Blanc professed the right to work—government intervention to guarantee full employment—certainly more appealing than the passive policy of “enrichissez-vous”. [33]

As with any other left-wing ideology, European governments suffocated socialist voices. In France, republican insurrectionist Armand Barbès and socialist activist Auguste Blanqui were condemned to life imprisonment in 1839 and 1840, respectively. [34] However, its effectiveness was merely transient; French King Louis-Philippe I’s obstinate neglect of bourgeois exploitation could only warrant protest, setting the political climate of the 1830s and 1840s. For instance, the three Canut Revolts (in 1831, 1834 and 1848) resulted from the refusal to impose a minimum wage to maintain a comfortable standard of living for Lyon silk merchants. [35]

In the 1840s syndicalism [j] also entered the public conscience; [36] workers of like professions longed to unite in large entities “trade unions” (or, labour unions) and acquire considerable political influence to safeguard their rights. [37] One of the first unions, the Luxembourg Commission, would be established only after the French Revolution of 1848. [38] Other European populaces were less exposed to socialist writings but still inadvertently cherished their message, being besieged by class struggles. American author Harold K. Schellenger Jr. notes that ‘socialism came late to Germany’ but, nonetheless, ‘from 1815 to 1848 German politics was characterised by suppression of the embryonic working class’. [39]

Barricade on the rue Soufflot by Horace Vernet (1848) depicting the June Days uprising in Paris: the red flag of socialism and protestors' common attire reflects the prevalent role of the proletariat in the 1848 Revolutions, reflecting the Marxist idea of "class struggle".

Liberalism and Democracy

Calls for a liberal democracy were amplified following the intransigent restoration of the conservative order in the Congress of Vienna; any mention of liberalism, republicanism or popular sovereignty reminiscent of the French Revolution of 1789 was to be expunged, even by military force if necessary. Emperor Napoleon I’s dissemination of the French Revolution’s groundbreaking Enlightenment ideals in his continental conquests from 1799 to 1815 had illuminated the educated masses on the necessity of a democratic government, checked by extensive voting rights and a constitution. [40] The Napoleonic Code imposed on most of Europe during this epoch borrowed several principles from the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. For instance, its first article posits that ‘personal serfdom shall be abolished without indemnification’. [41] Whilst these policies were reversed by the Concert of Europe after the Wars of the Sixth and Seventh Coalitions, citizens’ memory of a more liberal past could not be erased.

American historian Arnold Whitridge notes that French Prime Minister F. Guizot—according to K. Marx and F. Engels, one of the proletariat’s archnemeses along with Pope Pius IX, Tsar Nicholas I and Prince Klemens von Metternich [42]—believed in a government ‘in which the voters were limited to the aristocracy and the upper bourgeoisie represented the summit of enlightenment’, [43] ironically qualified him as one of the most liberal politicians in continental Europe which basked in the shade of absolute monarchism. In fact, most other European sovereigns, entrenched in their militant faith in divine right and not requiring consent from the public to rule, went further than curbing voting rights and outright prohibited the expression of political opinions. [44] The architect of the post-Napoleonic Wars conservative order Prince Metternich enforced the Carlsbad Decrees in 1819 which imposed stringent restrictions on university students and the press’ freedom of expression. [45] The educated middle class enshrining the French Revolution’s liberalism was consigned to private locations; such secret societies as the Carbonari had to operate underground in the 1820s and 1830s. [46]

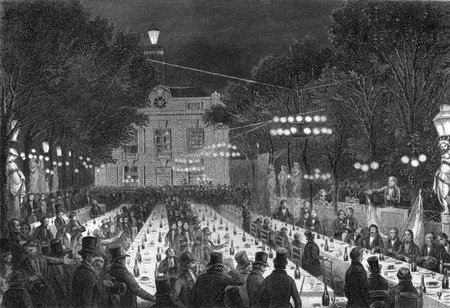

The suppression of popular anti-monarchical sentiment was sustained throughout these decades as few fruitful revolts occurred. Whilst some succeeded, such as the July Revolution in France and the Greek War of Independence, most that sprung up—from the Trienio Liberal in Spain in the early 1820s to the 1830–1831 November Uprising in Poland—were quelled by intervention from the great powers of the Concert of Europe: namely, the Holy Alliance of Prussia, Austria and Russia. [47] The Troppau Protocol enacted in 1820 [k] could put a lid on the broiling pressure of public discontentment at the conservative status quo for no more than twenty-eight years. [48] In France, the 1848 suspension of the campagne des banquets serving as mild political discussion hubs proved the straw that broke the camel’s back; the liberal educated masses could silence themselves no longer. [49]

Chartism—progressive reforms towards universal male suffrage in the United Kingdom—gradually gained steam among Whigs and played an instrumental role in ensuring public support for liberal reform in Europe. [50] The Reform Act of 1832 rendered one-fifth of adult males eligible to vote, which eclipsed King Louis-Philippe’s electoral reforms achieved during his reign; poll taxes were marginally reduced and the electorate merely expanded from 0.3% of the population (1830, pre-July Revolution) to 0.5% (1830, post-July Revolution) and eventually to 0.7% (1848), refusing to expand suffrage to the lower and middle classes. [52]

Most continental European nations also lacked a parliamentarian model of government whereby legislative powers would be devolved from an autocrat to an elected body of officials; for instance, Prince Metternich constantly overruled the will of the German Confederation’s Diet to advance his agenda. [53] The Hungarian Diet also existed as an independent entity from the Austrian government but was ‘dominated by the gentry’ instead of the working classes, comprising well over eighty per cent of the population. [54] The underlying national sentiment hankered for popular sovereignty, as stated in the third article of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen: ‘The principle of any sovereignty resides essentially in the Nation’. [55]

The "campagne des banquets" (banquets campaign): the suspension of mass gatherings as these was perceived as authoritarian and contradictory to the constitution's principles, expediting the French Revolution of 1848.

Nationalism

Whilst not as crucial as the other factors, nationalism—the collectivist movement uniting people of a particular culture (especially language) under one nation—played a role in fostering revolutionary sentiment, but this was ‘almost exclusively confined to those who were literate and familiar with the arts’. [56] This arose from the Napoleonic Wars, in which fragmented nations of a common language were consolidated for the first time, such as the hundreds of member states of the Holy Roman Empire being amalgamated into the Confederation of the Rhine in 1806, and certain ethnically unique nations were broken off, such as the Duchy of Warsaw (Poland) being granted independence from Russia.

In the Congress of Vienna, nationalism was the great powers’ pre-eminent sitting duck, reversing any smidgeon of recognition of the right to self-determination. [57] [l] Between 1815 and 1848, both ethnically “conjoined” populaces, such as the Austrian Empire comprising nationalities amount to double digits (including Germans, Hungarians, Ruthenians, Poles and Italians), and ethnically “disjoined” populaces, such as the German Confederation dividing the German-speaking world into thirty-nine independent states, collectively reflected on this state of cultural dismemberment. [58] The conclusion was unanimous: nations had to be based on a common linguistic identity. [59]

This was witnessed in the Italian states; the Carbonari lay the groundwork for the Risorgimento—the unification of nations in the Italian peninsula through the elimination of overbearing Austrian influence. [60] The strategy towards the Deutsche Einigung (German Unification) in the German Confederation was similar. [61] Nowhere did ethnic tension flare more than within the Austrian Empire; the Hungarian freedom fighter Lajos Kossuth and Czech patriot František Palacký were convinced that their ethnic minorities could not thrive within the empire’s folds and had to secede. [62] Calls for further devolution of powers to the individual parliaments started resounding.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire's ethnic composition in 1910—the same as the Austrian Empire's in 1848 except for the absence of Lombardy–Venetia and the presence of Bosnia and Herzegovina; the prevalence of multiple nationalities collected into one political perpetuated instability in the empire such that sporadic nationalistic protests erupted in 1848 and 1849.

Assessment

The 1848 Revolutions were destined ever since the conclusion of the previous onslaught of revolution emanating in 1789 by which workers and peasants alike would vindicate themselves for European sovereigns’ sordid neglect of their dignity in the Congress of Vienna. Marxists claim that 1848 was a microcosm of the proletariat’s final stand against the bourgeoisie’s tyranny and the first step to a pertinent path towards the dictatorship of the working masses; it was destined since the dawn of history, itself perpetually plagued by class struggles. That year’s revolutions are often labelled as the Springtime of the Peoples since they were the first popular revolts motivated by unhinged vitriolic liberalism. Another appropriate moniker could be the “Fall of the Tyrants” since Prince Metternich’s conservative order was fractured indelibly; it would finally collapse by the First World War’s end.

All the causes of the 1848 Revolutions—the First Industrial Revolution, famines, liberalism, socialism/syndicalism and nationalism—can be summarised in one word: emancipation—the people’s hankering for emancipation from the handcuffs of callous conservatism secured by the bourgeoisie’s dominance and their liberation into a newly found utopia of freedom. Indeed, freedom would not arrive in 1848, but our ancestors’ audacious yet tenacious defiance of the oppressive status quo paved the road for the liberal existence most modern European societies can languidly delight in without having to lift a finger to their governments.

Notes

[a] In Marxist ideology, the "proletariat" is the collective term for the working classes whilst the "bourgeoisie" refers to the managerial class—that controls the proletariat. The dictatorship of the proletariat is an inevitable consequence of the communist revolution espoused in Marxist literature by which the working classes rise up against their oppressors and take over state power.

[b] In the nineteenth century, Moldavia and Wallachia were the predominant Romanian principalities.

[c] Most historians agree that there have been four industrial revolutions (periods of rapid industrialisation). This blog focuses on the first one, occurring from c. 1760 to c. 1840, characterised by the mass employment of steam power as an energy source and the development of factories and railways. The Second Industrial Revolution (c. 1870–1914) oversaw the burgeoning of assembly lines and electricity, the Third (c. 1947 to present) concerns the advancement of computer and automation technology, and the Fourth (c. 2010s to present) strives for the enhancement of artificial intelligence and cybertechnology.

[d] In simple terms, a Malthusian catastrophe (also referred to as a "Malthusian trap" or "Malthusian crisis") posits that under exponential population growth, resource growth remains linear and hence can never meet the population's demands. Whilst most economists dismiss this theory nowadays, it was potentially true in Malthus' time (the early nineteenth century).

[e] The Romantics were a group of British, or, more broadly, European and American, writers prevalent towards the eighteenth century's end and the nineteenth century's first half who espoused an anti-urbanisation/industrialisation viewpoint, emphasising the necessity of humankind's integration with nature. Victorian-era authors tended to be in accordance, highlighting the destitute conditions of urban workers.

[f] The renovations in France during Emperor Napoleon III's reign, particularly centred on Paris, aimed at remedying the abounding squalor in urban regions owing to the effects of the First Industrial Revolution. They were conducted by the Seine prefect Baron Haussmann from 1853 to 1870. The public works projects involved destroying dilapidated, antiquated accommodation in place of modern residences, widening streets and passages into boulevards to ease traffic, overhauling and expanding sewage systems, establishing spacious gardens to aerate the environment and introducing gaslights.

[g] Laissez-faire economics, a cornerstone capitalist tenet, is the devolution of government economic management to the free market; so, non-intervention in the affairs of businesses such as wage/price controls.

[h] Free trade is the engagement in international trade with little to no tariff barriers—limited taxes on imported and exported goods. This contrasts with protectionism, the extensive imposition of tariffs on foreign goods.

[i] Okun's Law is an empirically, not necessarily proven, observed relationship between GDP and employment, stating that increased productivity and manufacturing rates correlate with rising employment, and vice versa.

[j] Syndicalism is fundamentally the left-wing ideology advocating the consolidation of political power by trade unions such that the proletariat can seize control over their means of production and supersede the bourgeoisie and state's authority.

[k] The Troppau Protocol, promulgated in the 1820 Congress of Troppau and ratified by the Holy Alliance, justified military intervention from the European great powers in nations undergoing mass protest—a means to stifle liberalism, republicanism and any other undesirable ideology in the continent. It declares: 'If states which have undergone change in government due to a revolution […] threatens other states, the powers bind themselves, by peaceful means, or if need be, by arms, to bring back the guilty state into the bosom of the Great Alliance [the Concert of Europe]'.

[l] In a nationalistic context, the right to self-determination guarantees the formation of governments and states representative of their citizens' identity, culture and exigencies. In mid-nineteenth-century Europe many ethnicities with the Austrian Empire espoused this nationalistic ideal and revolted to secede and form their own political entities.

Summary

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION

- Mass urbanisation and industrialisation coincided with the burgeoning of capitalism as Europe's leading economic system, securing the bourgeoisie's control over the proletariat.

- Agrarian families migrated en masse to urban areas to make a living, oversaturating cities.

- Economic conditions became adumbrated by Malthusian catastrophes and stagnant wages (iron law of wages).

- Social conditions were plagued by poor sanitation, squalor, overcrowding, pollution and grisly factory environments.

FAMINE

- The "Hungry Forties" abounded in crop failures and blights, leaving populaces impoverished and dependent on private charities; many perished or emigrated.

- The 1845 potato blight, the main culprit, devastated that year's harvest, bearing especially acute misfortune on Ireland.

- The harsh winter of 1846 to 1847 led to essential foodstuffs becoming unaffordable; the price of wheat double and that of grain rose exponentially.

- Governments, abiding by laissez-faire and protectionist policies, failed to take decisive action to reduce starvation levels.

RISE OF SOCIALISM

- The sheer hardships involved in factory work, a product of workers' deprivation of rights or protection, led to the popularisation of socialism and syndicalism in urban communities.

- The wealth and political gap between classes was manifested by the government's stubborn consent of unbridled capitalism; wages and tariffs were kept low.

- Cost of living and unemployment crises dominated cities; government intervention in the running of factories, such as securing the right to work, regulating degrading labour and ensuring equitable distribution of power between the bourgeoisie and proletariat, was not fulfilled.

- Any opposition to the status quo, such as socialist writings (e.g., Blanquism) and protests (e.g., the Canut Revolts) were merely suppressed.

- To topple the bourgeoisie's ascendancy, many started favouring the establishment of trade unions to protect workers' rights—syndicalism.

LIBERALISM AND DEMOCRACY

- The French Revolution's liberal and democratic principles, disseminated during the Napoleonic Wars, enlightened the educated middle class to fight for political representation, oppugning the European absolutist/autocratic monarchies with severely limited or no parliaments and suffrage.

- Any opposition was stifled, including enjoining the freedoms of expression, assembly, the press and petitioning the government.

- Chartism—the mandating of universal male suffrage—was partially recognised in the United Kingdom, coveted by the rest of the continent.

- Parliamentarian forms of governments were desired, granting representation of fairly elected officials to check the monarch's excessive executive and legislative power.

NATIONALISM

- Ever since the partial recognition of self-determination in the Napoleonic Wars and its subsequent annulment in the Congress of Vienna, ethnic communities longed for more autonomy in the form of independent parliaments or even nations.

- In the multinationalistic Austrian Empire, such figures as the Hungarian Lajos Kossuth demanded further devolution of federal powers or outright secession of their ethnic groups.

- Italian and German states (i.e., within the German Confederation) started struggling for their unification as a single political entity under a common language.

References

[1] International Marxist Tendency 2022.

[2] Marx & Engels 1969, p. 14.

[3] London Review of Books (LBR) 2019, 0:11–0:37.

[4] Ibid., 0:38–1:18.

[5] Davidson 2012, pp. 136–138.

[6] Greasley & Oxley 1997, p. 940.

[7] Cartwright 2023.

[8] Beecher 2021, p. 42.

[9] Nardinelli.

[10] Cartwright 2023.

[11] Teleky 2012, pp. 1104–1106.

[12] Blake 1820; Nardinelli.

[13] De Moncan 2012, p. 10.

[14] Baldrick 2022.

[15] Abbot 2001a.

[16] Beecher 2021, p. 44.

[17] Vernon 2007, pp. 12–20.

[18] Abbot 2001b.

[19] Beecher 2021, pp. 43–45.

[20] Berger & Spoerer 2001, pp. 299–300.

[21] Baldrick 2022.

[22] Abbot 2001a.

[23] Greasley & Oxley 1997, p. 942.

[24] Cartwright 2023.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Marx & Engels 1969, p. 14.

[27] Fourier 1966.

[28] Beecher 2021, p. 58.

[29] Bellos 1987, p. 76.

[30] Berger & Spoerer 2001, p. 304.

[31] Ibid, p. 306.

[32] Dunham 1943, p. 117.

[33] Bhuta 2024, p. 44.

[34] Beecher 2021, p. 66.

[35] Ibid, p. 31.

[36] International Marxist Tendency 2022.

[37] Bhuta 2024, p. 63.

[38] Beecher 2021, p. XVII.

[39] Schellenger 1968, pp. 9–10.

[40] Davidson 2012, pp. 133–136.

[41] Sieyès 2002.

[42] Marx & Engels 1969, p. 14.

[43] Whitridge 1948, p. 265.

[44] Beecher 2021, pp. 6–7.

[45] Barnes & Feldman 1980, pp. 25–27.

[46] Kohn 2003, p. 33.

[47] Barnes & Feldman 1980, p. 32.

[48] Cassels 1996, pp. 45–47.

[49] International Marxist Tendency 2022.

[50] Gammage 1894, pp. 1–9.

[51] Ibid., pp. 149–152.

[52] Beecher 2021, p. 25.

[53] Barnes & Feldman 1980, p. 34.

[54] Beecher 2021, p. 8.

[55] Sieyès 2002.

[56] Cassels 1996, p. 56.

[57] Cassels 1996, pp. 43–45.

[58] Whitridge 1948, p. 268.

[59] Jelks 2022.

[60] Barnes & Feldman 1980, p. 91.

[61] Ibid., p. 91; Cassels 1996, p. 61.

[62] Whitridge 1948, p. 267.

Bibliography

For more information, one may consider consulting these sources; I primarily used these as sources in creating this blog. They are listed in their respective categories. The links appearing throughout the blog should also be consulted.

SOURCES

- Abbot, Patrick (2001). “The Famine 4: The Winter of 1846 to 1847”. wesleyjohnston.com.

- ——— (2001). “The Famine 5: The Summer of Black ‘47”. wesleyjohnston.com.

- Baldrick, Thea. (2022-11-06). “Irish Potato Famine: An Era of Starvation & Disease”. The Collector.

- Barnes, Thomas G., & Feldman, Gerald, D. (1980). Nationalism, Industrialization and Democracy 1815-1914: A Documentary History of Modern Europe Volume III. Lanham, United States: University Press of America. Accessed via Google Books.

- Beecher, Jonathan (2021). Writers and Revolution: Intellectuals and the French Revolution of 1848. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. Accessed via Google Books.

- Bellos, David (1987). Honoré de Balzac: Old Goriot. New York, United States: Cambridge University Press. Accessed via Google Books.

- Berger, Helge, & Spoerer, Mark. (2001). “Economic Crises and the European Revolutions of 1848”. The Journal of Economic History, vol. 61, no. 2, pp. 293–326. Accessed via JSTOR.

- Bhuta, Nehal (2024). Human Rights in Transition. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. Accessed via Google Books.

- Blake, William. (1820). Jerusalem: The Emanation of The Giant Albion § “Did those feet in ancient time”. Reproduced by hymnary.org.

- Cartwright, Mark. (2023). “Social Changes in the British Industrial Revolution”. World History Encyclopedia.

- Cassels, Alan (1996). Ideology and International Relations in the Modern World. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. Accessed via Google Books.

- Davidson, Neil (2012). How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions?. Chicago, United States: Haymarket Books. pp. 133–139. Accessed via Google Books.

- De Moncan, Patrice (2012). Le Paris d’Haussmann [Haussmann’s Paris] (in French). Ravières, France: Les Éditions du Mécène. Accessed via Wikipedia.

- Dunheim, Arthur L. (1943). “Industrial Life and Labor in France 1815-1848”. The Journal of Economic History, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 117–151. Accessed via JSTOR.

- Fourier, Charles (1966). Œvres complètes de Charles Fourier [Complete works of Charles Fourier] (in French). France: Éditions Anthropos. Accessed via Wikiquote.

- Grammage, Robert George (1894). History of the Chartist Movement, 1837–1854. Newcastle-on-Tyne: Browne & Browne. Accessed via Google Books.

- Greasley, David, & Oxley, Lee. (1997). “Endogenous Growth or “Big Bang”: Two Views of the Industrial Revolution”. The Journal of Economic History, vol. 54, no. 4, pp. 935–949. Accessed via JSTOR.

- International Marxist Tendency (2022). “The Permanent Revolution in Europe: 1848”. International Marxist University.

- Jelks, Stephanie (2022-05-12). “The Revolutions of 1848: A Wave of Anti-Monarchism Sweeps Europe”. The Collector.

- Kohn, Margaret (2003). Radical Space: Building the House of the People. Ithaca, United States: Cornell University Press. Accessed via Google Books.

- London Review of Books (LRB) (2019-02-27). “Christopher Clark: The 1848 Revolutions”. YouTube.

- Marx, Karl, & Engels, Friedrich (1969) [1848]. The Communist Manifesto. Moscow, Russia: Progress Publishers. Reproduced by Marxists Internet Archive.

- Nardinelli, Clark. “Industrial Revolution and the Standard of Living”. Econlib.

- Schellenger, Harold Kent (1968). The SPD in the Bonn Republic: A Socialist Party Modernizes § “A Short Story of German Socialism”. Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. pp. 9–10. Accessed via Springer Link.

- Sieyès, Abbé (2002) [1789]. Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen. Reproduced in English by Conseil Constitutionnel.

- Telkey, Ludwig. (2012). “History of Factory and Mine Hygiene”. Am J Public Health, vol. 102, no. 6. pp. 1104–1106. Accessed via PubMed Central.

- Vernon, James (2007). Hunger: A Modern History. Cambridge, United States: Harvard University Press. pp. 12–20. Accessed via Google Books.

- Whitridge, Arnold. (1948). “1848: The Year of Revolution”. Foreign Affairs, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 264–275. Accessed via JSTOR.

FURTHER CONSULATION

- Jelks, Stephanie (2022-05-12). “The Revolutions of 1848: A Wave of Anti-Monarchism Sweeps Europe”. The Collector.

- London Review of Books (LRB) (2019-02-27). “Christopher Clark: The 1848 Revolutions”. YouTube.

RELEVANT SELF-PUBLISHED BLOGS

- Brainstorm (2024-02-26). “The French Revolution Dictated 19th-Century Europe”. Jetpunk.

- ——— (2024-04-01). “Did the Congress of Vienna Succeed?”. Jetpunk.

- ——— (2024-04-15). “Why did France's Last King Fail?”. Jetpunk.

_________________________________________________________________________________

This blog is part of a set concerning 1848. The rest can be accessed from my History series.

i hate malthus i hate malthus i hate malthus i ha