‘One of the best fighters and leaders in the modern proletarian movement’: British communism and the memory of James Connolly, 1920-39

By David Convery

The 1916 Easter Rising was an event of importance not just in Ireland, but internationally. A revolt in the British Empire was a noteworthy event in any case, but coming in the capital of Britain’s neighbour, in the midst of a titanic war with Germany, it became world historic. It resonated particularly with those organising and agitating against oppression.

It was to serve as inspiration for separatist movements in India; for Marcus Garvey in his Universal Negro Improvement Association in Jamaica and the United States; and for people such as Lenin, who led the Bolsheviks to victory in Russia just over a year later.

Immediately grasping its significance, Lenin wrote of the rising that ‘A blow delivered against the power of the English imperialist bourgeoisie by a rebellion in Ireland is a hundred times more significant politically than a blow of equal force delivered in Asia or in Africa.’ However, he added, ‘It is the misfortune of the Irish that they rose prematurely, before the European revolt of the proletariat had time to mature.’[2]

James Connolly, one of the leaders of the 1916 Rising was widely praised by the communist movement after his death, including by the Communist Party of Great Britain.

In the years immediately after the Russian Revolution, Lenin and the Bolsheviks hastened to develop this maturity by assisting in the creation of communist parties worldwide, to be organised in the Communist International (Comintern), a world party of revolution. The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) founded in August 1920, was one of these.

From the beginning the CPGB took a keen interest in Ireland. Many of its members had a personal interest as Irish immigrants or descendants of Irish immigrants. For instance, its first chairman, Arthur MacManus, was born in Belfast but moved to Scotland at a young age. For all though, there was an immediate political interest, with the founding of the party taking place during a revolutionary upheaval in Ireland, which had begun with the Easter Rising.

The Rising had an added significance in that one of its leaders was a Marxist revolutionary, James Connolly, who had aimed not just for an Irish Republic but for a Workers’ Republic. Connolly was important to the CPGB not just because of ideas, but also because of who he was. For Connolly was not just an Irish revolutionary; he was part of the socialist movement in Britain too.

Born in Edinburgh in 1868, Connolly became involved in socialist politics from an early age. He had been secretary of the Scottish Socialist Federation, linked to the wider British-based Social Democratic Federation (SDF), before his arrival in Ireland in 1896 where he founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP). Connolly was also a founding member and guiding spirit of the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), formed in 1903 as a split from the SDF, particularly in Scotland. Connolly maintained links with the socialist movement in Britain while he lived in Ireland and the United States.

For instance, he frequently wrote for Forward, the paper of the Independent Labour Party in Scotland, and during the 1913 Dublin Lockout, he spoke at solidarity meetings in Britain, and at a special congress of the Trades Union Congress in London on the issue.

When the newspaper he edited, the Irish Worker, was suppressed for its anti-war stance in December 1914, Connolly went to Glasgow, where MacManus, then of the SLP, printed its brief replacement, The Worker, and smuggled it to Dublin.

The Communist Party of Great Britain itself was formed as an amalgamation of activists from previously existing socialist organisations in Britain, the majority from the British Socialist Party, which had evolved from the Social Democratic Federation, while much of the leadership came from the Socialist Labour Party. Many of its members had personally known Connolly and the new organisation could, with some legitimacy, also claim a direct political link to him.

Although there was to be very little discussion of Connolly the man or his ideas over the next twenty years, Connolly’s name was consistently invoked by the CPGB as an unquestionable hero, ‘one of the undying figures of the world working-class’,[3] continuously used as a benchmark, both to inspire the pursuit of his goal of a Workers’ Republic, or, conversely, to highlight hypocrisy and opportunism. This was particularly true in relation to Ireland, but occasionally with regard to events and individuals in Britain too.

Revolution and War

From 1920-23, during the Irish War of Independence and Civil War, the memory of Connolly was used as part of an immediate and ongoing process, serving a practical purpose as a means to measure the political and military manoeuvrings of various factions in the Irish revolutionary forces.

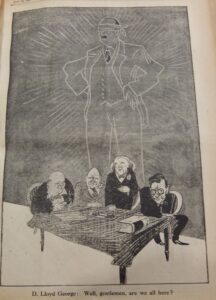

A superb illustration of this is a cartoon which appeared in the CPGB’s weekly paper, The Communist, at the time of the Truce between the IRA and the Crown Forces in July 1921. The image shows representatives of the British cabinet meeting with Éamon de Valera.

The tag line has Lloyd George saying, ‘Well, gentlemen, are we all here?’ and shows the blindfolded ghost of Connolly hovering over them, a reminder not only of the manner of his execution at the hands of the British, but a warning that de Valera might be about to sell short the struggle that Connolly had pursued.[4]

The new Communist Party of Ireland, founded in the autumn of 1921, opposed the Treaty with Britain which created the Irish Free State,[5] as did the CPGB, and were supported in this by the Comintern. Indeed, Willie Gallacher, later Communist MP for West Fife, claimed to have travelled to Dublin to inform leading republicans about the capitulation of their representatives in London to British demands in December 1921, and urging their arrest upon their return.[6] In the immediate aftermath of the Treaty, the CPGB referred to the new southern Irish government as the ‘Royal Irish Republic’, and later as the ‘Imperial Free State’, and often used the memory of Connolly and 1916 to support their position.

The CPGB referred to the pro-Treaty government as the ‘Royal Irish Republic’, and later as the ‘Imperial Free State’, and often used the memory of Connolly and 1916 to support their position

In the tense period in early 1922 before open hostilities broke out between pro- and anti-Treaty supporters, the CPGB asserted that ‘we, on every possible ground, are on the side of those who carry on the tradition of 1916.’[7]

In another piece, they called ‘upon the toiling masses to prepare themselves for unflinching support of those Republicans who, refusing to be associated with this Treaty, persevere with the struggle for the ideals of Pearse and Connolly.’ In order to muster these ‘toiling masses’ in the pursuit of a Workers’ Republic, it claimed that a basis of agreement between urban and rural workers existed not only because of their ‘common antagonism’ against the capitalist class, but because ‘there exists … particularly since Pearse and Connolly, a common tradition of “national right” to the control of the material resources of Ireland which, accepted and cherished by these classes, runs directly counter to the Capitalist ideology.’[8]

At their October 1922 conference they appealed to the rank and file of the Irish labour movement:

to be true to the cause for which their leader, James Connolly, sacrificed his life, dismiss the leadership of to-day, and rally to a new leadership which will dare to line up the forces of Labour with the Communist Party of Ireland and the I.R.A. in the fight against imperialism. This is the only way the workers and peasants of Ireland can defeat the forces of reaction and secure the Workers’ Republic to which they are pledged.[9]

With the end of the Civil War in 1923 and the consolidation of the Free State, Connolly’s name was used less frequently, mostly in articles that can be broadly placed in three categories: commemorative pieces on the Easter Rising; attacks upon Arthur Henderson and the British Labour Party; and in discussion of major events in Ireland and the tasks facing Irish communists.

TA Jackson and the romance of the Rising

The anniversary of the Easter Rising was commemorated most years in the British communist press, usually as an editorial piece, but sometimes in longer, dedicated articles. All glorified the rebels of Easter Week, but otherwise the pieces can generally be divided into two types. The first typically remembered the Rising for its own sake, recollecting the events and the main protagonists, while the second used the memory of the Rising to draw political lessons, usually related to the current needs and antagonisms of the communist movement.

The former were often the work of Thomas Alfred Jackson, born in London in 1879. Jackson had no Irish ancestry but became active in the socialist movement in Clerkenwell in the 1890s, a traditional hotbed of radicalism where the Fenians had once been strong.

Communist activist T.A. Jackson developed a romantic narrative of the Irish struggle for independence, not dissimilar to Connolly’s Labour in Irish History

His friend and comrade, Con Lehane, had been a member of Connolly’s ISRP in Cork, and helped him develop a keen interest in the history of Ireland’s national struggle. Jackson would later become known for his book Ireland Her Own first published in 1946, which developed a romantic narrative of the Irish struggle for independence, not dissimilar to Connolly’s Labour in Irish History, and which he dedicated to Lehane.

The forerunners of this can be seen in his articles in the British communist press in the 1920s and 1930s on the Easter Rising. These tend to be long, but gripping, heroic narratives, with a level of detail absent from other accounts produced by the CPGB. Although the analysis tended to be simplistic, Jackson nevertheless had some interesting insights. ‘To Connolly’s influence over Patrick Pearse’, said Jackson,

is no doubt due to the fact that in the proclamation of the Irish Republic, a clause expressly affirmed the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of the wealth of Ireland, to Pearse’s influence upon Connolly is perhaps due his willingness to believe in the saving power of a ‘blood-sacrifice’ – the revitalising power of a defiant deed, however disastrous to its enactor.[10]

In 1929 the communist weekly, then known as Workers’ Life, dedicated a full page to remembering the Easter Rising, with an article written by Jackson. Here Jackson singled out not only Connolly, but also Thomas Clarke and Patrick Pearse, with particular praise upon the latter, elevating his thinking almost to the level of Connolly – a conclusion which other Marxists shied away from.

This he based upon Pearse’s 1916 pamphlet The Sovereign People, highlighting in particular his answer to the question of ‘who is to rule Ireland when Ireland is free?’ as being the people, ‘the great, splendid, faithful, common people.’ Jackson argued that:

Passage after passage in the same pamphlet anticipates the famous sentences in the Proclamation of the Republic which declare ‘the right of the people of Ireland to the ownership of Ireland, and the unfettered control of Irish destinies to be sovereign and indefeasible,’ and guarantee ‘equal rights and opportunities.’ Together they show beyond question that Pearse interpreted them (for all his ‘mysticism’) in the same way as did Connolly, the Revolutionary Marxist.[11]

This comparison was peculiar in itself but was especially so given the timing. In 1929 the communists were pursuing the Comintern’s sectarian ‘third period’ policy of ‘class against class’, with them going it alone in the class struggle and denouncing all others as obstacles to the advance of the working class.

Yet here Jackson was deeming heroic the alliance between a revolutionary Marxist and those who in other contexts would be disparagingly labelled as ‘petit bourgeois nationalists.’ This was likely no coincidence, for that same year Jackson was dropped from the Central Committee of the CPGB for his opposition to the policy of ‘class against class’.[12]

Accordingly, his article was criticised in the next issue of Workers’ Life. Helen Crawfurd – who had personally known Connolly – took him to task for its ‘romantic’ take, being ‘bitterly disappointed that the article took the form of mere narrative and that no comment was made either on the events that led up to Easter week or on the treacherous role of the British Labour Party during this period.’[13] Here was a pointer to the second category to which Connolly’s memory was used by the CPGB.

Who killed Connolly?

The most recurring example of this was the evocation, year after year, of the Easter Rising as a stick with which to beat Arthur Henderson and the British Labour Party. Henderson was a major figure in the Labour Party being at various times party secretary, party leader, Home Secretary and Foreign Secretary.

In 1916 he had been a member of the British Cabinet which introduced martial law in Ireland, resulting in the execution of the leaders of the Rising. Henderson then, became a useful figure for the CPGB to showcase the perfidious nature of the Labour Party, and to draw corresponding political conclusions.

British Communist publications in the later 1920s blamed Labour Party figure Arthur Henderson, a minister in the wartime government in 1916, for the execution of James Connolly.

For instance, in a 1928 editorial piece in Workers’ Life on the Rising, it was noted that:

At the end of the rising, Connolly, the leader of the Irish Labour movement, was taken out and shot in cold blood. Mr. Arthur Henderson, the present secretary of the Labour Party, was the Labour Party’s representative in the Cabinet at the time, as Home Secretary. On him, and on the whole Labour Party leadership, falls particular responsibility for the execution of Connolly, since British Imperialism, at death grips with its German rival, would never have dared to shoot were it not certain of Labour Party support.

Referring to Labour’s present stance on ‘the use of soldiers in industrial disputes’, the article added that ‘It is worth while remembering these things, because the Labour Party leadership … is still prepared to shoot workers in defence of capitalist interests.’[14]

Denunciations of Henderson’s alleged role in the execution of Connolly featured in pieces commemorating the Easter Rising, but also in articles critiquing him for such varied reasons as his request for information regarding ‘religious persecution’ in Ukraine; on his selection as leader of the Labour Party in 1931; and on his supposed commitment to disarmament.[15]

So common were these denunciations that at a meeting in Manchester in 1931 where Henderson was accosted with the question ‘Who killed Connolly’, the Daily Worker reported that ‘I have heard that before’ was Henderson’s ‘indifferent reply.’[16]

In 1936 the CPGB also used Connolly to attack the Independent Labour Party and one of its leading figures, James Maxton, claiming that, as in 1916 it condemned Connolly and his comrades for taking up arms ‘in the defence of their country, so Maxton blames the Abyssinians for having (under encouragement from elsewhere), taken up arms in defence of their country.’[17]

Lessons

Other pieces, spread over many years, recalled Connolly’s name for immediate political purposes in Ireland, with Connolly put on a pedestal to highlight the shortcomings of De Valera, the IRA, the Labour Party, and many others, and portraying the communists as the inheritors of Connolly’s ideas and the only ones dedicated to the achievement of his goal of a Workers’ Republic.

Connolly’s heroism was taken as a given in all the articles in which he was mentioned, but analysis of his ideas was sorely lacking. When they were discussed, it was usually a case of presenting some quotes of his in opposition to the First World War, or in support of Ireland’s right to nationhood.[18]

Connolly’s ‘heroism’ was taken as a given but analysis of his ideas was sorely lacking. Rather he was deemed to have taken ‘the same line as Lenin’.

His ideas were not critiqued and instead, Connolly was co-opted for the modern communist movement, placed alongside Russian contemporaries he never knew. A sub-heading in a 1931 article in the Daily Worker claimed that Connolly had the ‘Same Line as Lenin’, and although the Easter Rising had failed, ‘it was the herald of the triumphant Russian Revolution of a year later.’[19]

A 1939 article also claimed that Connolly approached ‘the position of Lenin and Stalin on the question of wars of national liberation.’[20]

By the 20th anniversary of the Rising in 1936, the line emanating from Moscow had changed from the previous policy of ‘class against class’. Stalin was now pursuing an alliance with Britain and France to stave off the threat of war with Nazi Germany, and communists were allying themselves in ‘people’s’ or ‘popular fronts’ with the very ‘labour-reformists’ and ‘petit-bourgeois nationalists’ they had denounced a few years ago, to stymie the threat of fascism at home.

In the spirit of the times, a Daily Worker article rebranded the leaders of the Easter Rising as ‘Fighters for Peace’ during the war. The alliance of Casement, Connolly, Pearse, and Clarke was portrayed as having contemporary resonance, being ‘the beginning of a People’s Front’. Indeed, echoing the piece for which Jackson was criticised in 1929, the author Montagu Slater emphasised, ‘You could hardly find four more striking representatives of a People’s Front wherever you looked.’[21]

The man behind the myth?

What is also lacking in all these pieces is a focus on Connolly as a person. This is especially unusual given his stature in the movement and the fact that many who had known him were still alive and active in the Communist Party.

Even his SLP comrade Arthur MacManus neglected any personal insight into him, being content to offer platitudes declaring him ‘one of the outstanding international figures of our movement’, with characteristics of self-sacrifice, valour, fortitude and courage, and, like other articles, comparing him to a Western Marxist version of Lenin.[22]

Only a minority of those who had known Connolly chose to write about the man rather than the myth.

Tom Bell, another former member of the SLP, offers the only substantial personal reminiscences of Connolly. Bell portrays Connolly during his time in Scotland in 1902-03 as a well-read man who could argue about Shakespeare as much as Marx, and highlights his intelligence, wit and repartee in the speeches he gave whilst agitating for the SDF and planning for the launch of the SLP.

It is also particularly interesting as, of all the pieces discussed so far, Bell’s is the only one which criticises Connolly, albeit in a minor way. Bell asked Connolly at one point how he could reconcile his Catholicism with the materialist concept of history. As Bell recalled:

His reply was that in Dublin the children who go to the Catholic Church invariably turn out rebels, but if they are brought up in the Presbyterian Church they turn out howling Jingoes. To me this was not a convincing argument, but it was left at that. I was too young and inexperienced to controvert him.[23]

A new generation

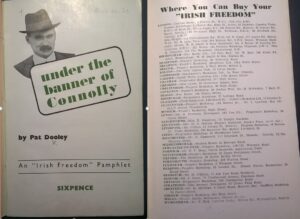

From the mid-1930s there appears a more reflective approach to Connolly, rather than just an invocation of his name in defence of present political positions.

Perhaps this was because in the 1920s and early 1930s, Connolly was still in living memory, the events of the First World War still fresh, and Connolly’s contemporaries were leading the labour and socialist movements of the day.

Connolly’s actual writings and ideas became more prominent in the 1930s.

Nevertheless, it was still surprising given his importance to the development of Marxism in these islands. By the mid-1930s however, there was a new generation, for whom the life and ideas of Connolly were not common knowledge. It was this generation, particularly of Irish socialists resident in Britain, who would work in a concerted way to bring his name and ideas into the British labour movement through the Connolly Club founded in 1938, and renamed the Connolly Association in 1943.

The CPGB for its part, although giving lots of publicity to its events, did not take an active role in responding to their call for greater remembrance and discussion of Connolly, appearing rather to have been happy that someone else was doing it.

Ultimately, then, despite his importance to the development of British Marxism, indeed, arguably the most original and intelligent Marxist that Britain has ever produced, he remained at most a useful martyr to call on, his ideas never receiving anywhere near the sort of engagement in the British communist press as Lenin’s, and consistently being stretched to defend the present party line.

It was left to the next generation of Irish in the Connolly Association to remember him not only as a martyr, but as a thinker, and as a real guide to action, rather than just a heroic name.

References

[1] Title is a quote from Communist Review, July 1925, p. 119.

[2] https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/jul/x01.htm

[3] Daily Worker, 7 April 1936, p. 4.

[4] The Communist, 23 July 1921, p. 3. The cartoonist went by the pen name ‘Espoir’. His real name was Will Hope, a young Australian. See Francis Meynell, My Lives (London: The Bodley Head, 1971), pp. 127-8.

[5] Workers’ Republic, 17 December 1921, pp. 1-2.

[6] Workers’ Voice, 21 May 1932, p. 2; William Gallacher MP, The Rolling of the Thunder (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1947), pp. 53-6.

[7] The Communist, 14 January 1922, p. 5.

[8] The Communist, 15 April 1922, p. 10.

[9] The Communist, 14 October 1922, p. 5.

[10] The Workers’ Weekly, 2 April 1926, p. 4.

[11] Workers’ Life, 5 April 1929, p. 5.

[12] Stuart Macintyre, A Proletarian Science: Marxism in Britain, 1917-1933 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1986), p. 104.

[13] Workers’ Life, 12 April 1929, p. 4.

[14] Workers’ Life, 27 April 1928, p. 2. This is slightly inaccurate. Henderson was not yet Home Secretary, being appointed to the position later in the year, but he was a cabinet member.

[15] See Daily Worker 26 February 1930, p 6; 26 August 1931, p. 3; 25 July 1931, p. 4.

[16] Daily Worker, 30 March 1931, p. 3.

[17] Daily Worker, 11 April 1936, p. 3.

[18] An exception is arguably Pat Devine’s article ‘Easter Week, 1916’ in Labour Monthly, April 1936, pp. 227-36, but even this largely focuses on the war and the Rising.

[19] Daily Worker, 4 April 1931, p. 4.

[20] Daily Worker, 12 May 1939, p. 2.

[21] Daily Worker, 13 April 1936, p. 4.

[22] Communist Review, May 1924, pp. 36-8; July 1925, p. 119.

[23] Labour Monthly, April 1937, pp 241-7 (quote on p. 245).