HyperNormalisation may be Adam Curtis’s most ambitious project. In typically studious fashion, the film charts 40 years and about three continents through two hours and 45 minutes of archive footage. The central premise, in lay terms, is that loads of people keep making stuff up to either deceive us or to avoid dealing with the complexities of the real world.

“…politicians, financiers and technological utopians, rather than face up to the real complexities of the world, retreated. Instead, they constructed a simpler version of the world, in order to hang on to power.”

Given these lessons about truth and cynicism, it may be advisable to apply a pinch of salt even to Curtis. Nevertheless, here are six things we took away…

1. We’re all narcissists…

BBC

BBC

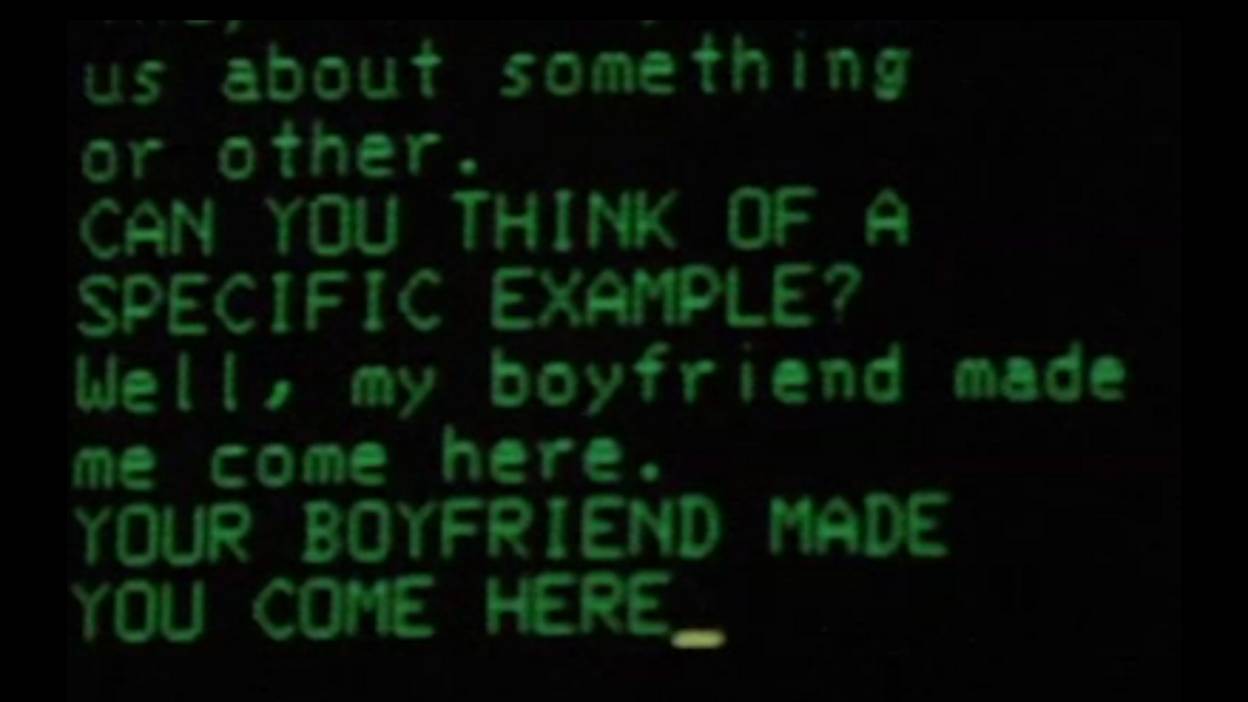

One of the key narratives of this film is that collective ideals have been replaced in the West since the 1970s with a growing individualism. One tale in particular captures this idea. It’s about a 'computer therapist' system that was created by a programmer at MIT, Joseph Weizenbaum, during the 60s. The system was called ELIZA. You enter your problems and it responds. Essentially, it was a language-processing tool. It picked up what you’d written and repeated it back to you, often in the form of a question.

BBC

BBC

“My husband says that I’m always depressed.”

“I’m sorry to hear that you’re depressed.”

Obviously, the computer doesn’t actually empathise. What Jospeh Weizenbaum discovered though, was that this didn’t matter. The therapy worked. For Weizenbaum, this was evidence that what people really respond to is when they see themselves reflected back. This paved the way for the 'if you liked that, you’ll love this' principle of marketing and filtering information on the web.

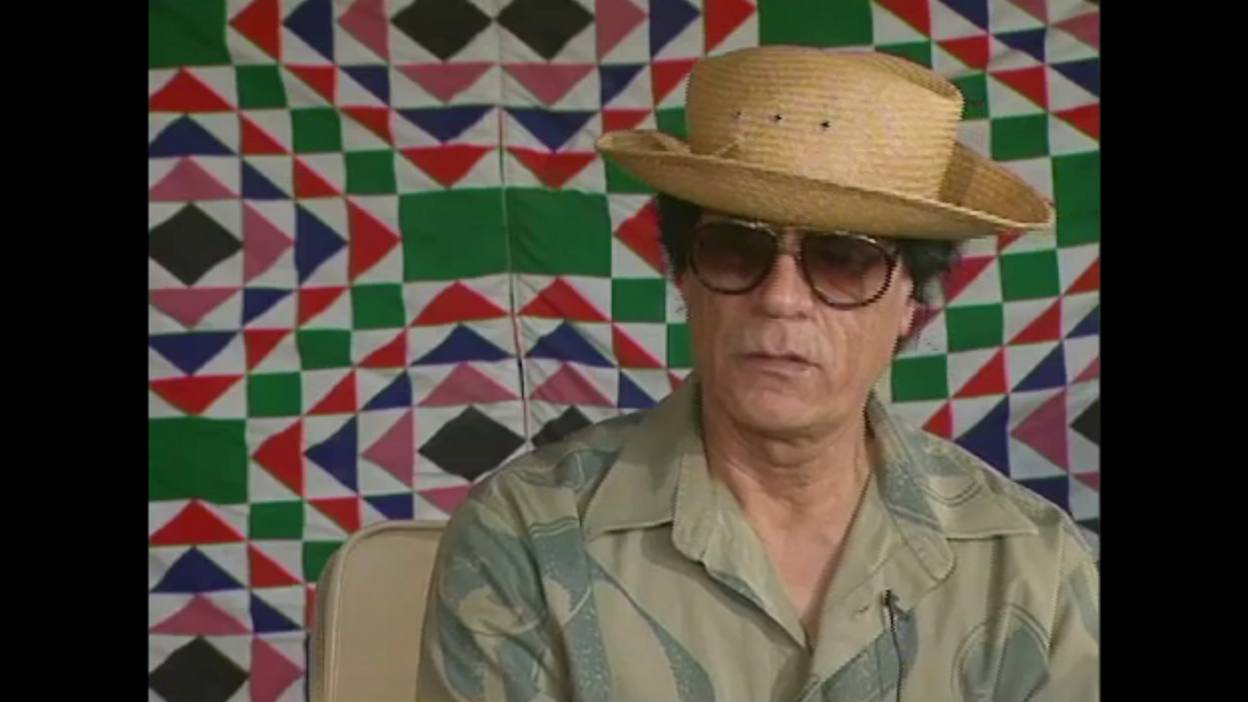

2. Colonel Gaddafi was perhaps less dangerous than you think…

BBC

BBC

If you’ve seen any of Curtis’s other films, then you won’t be surprised to learn that HyperNormalisation works on the general paradoxical premise that, at least for the last half-century, the aims of Western neoliberal powers and Middle East Islamic powers have often overlapped. Colonel Gaddafi seems the ultimate example of this. Throughout the film, he’s shown as a bogeyman, whose power exists as much in the mind as in the physical world. This is perception management – a term Curtis returns to a lot during the film.

For successive US Presidents and UK Prime Ministers, he is used as a scapegoat for various problems, deflecting attention from the real threats posed by President Hafez al-Assad in Syria. Perhaps more strange, Gaddafi himself seems complicit. Why? The film suggests that these accusations helped him cultivate his reputation as a Middle-East Revolutionary.

Perhaps the most shocking example Curtis uses is that Gaddafi claimed responsibility for the Lockerbie bombing, which some claim he had nothing to do with, before later claiming to have ended a chemical weapons programme that he had never began.

3. The Truth is out there…

BBC

BBC

…but, surprise, surprise, not all may be as it seems. In the 80s, theories about UFOs were everywhere. There were stories about leaked secret US government documents, which proved the existence of alien lifeforms visiting Earth. It was a big cover-up.

Curtis suggests that what was really happening here was a double bluff.

“…the reality was even stranger. The American government was making it all up. They had created a fake conspiracy to mislead.”

Curtis shows that what these misdirected hicks were really looking at were not UFOs at all, but a new breed of smart American weapons that were being developed as a deterrent to Russia.

“The government wanted to keep the weapons secret, but their appearance couldn’t always be disguised.”

He shows that certain individuals were even identified to help spread these rumours. If true, it’s a truly bizarre case of a government creating a red herring to distract the public from some agenda.

4. People are more interested in porn than terrorism…

BBC

BBC

In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, programmes were set up to monitor webcam interactions, with the aim of foiling potential terrorist plots. One of these operations was called Optic Nerve. Apparently, it didn’t pick up a single terrorist threat. Instead, what was discovered was a “surprising” number of people using webcams to show others “intimate parts” of their bodies…

5. The house (almost) always wins. Just ask Donald…

BBC

BBC

During the 1990s, Donald Trump employed the services of a man called Jess Marcum at his casinos. In Las Vegas, Marcum was known as 'the automat', on account of his great ability to count cards. Trump needed him desperately. A Japanese billionaire on a winning streak was bleeding his club dry and debts were being called in. Trump needed Kashiwagi to lose.

Marcum suggested a high-stakes game that he was certain the Japanese gambler would fail at. He was right. Trump was elated. But then something happened that couldn’t be predicted – Kashiwagi was murdered in his palatial home - probably by gangsters. Donald never got his money.

This serves as an allegory for Curtis of the fallibility of predictive systems and the inevitability of anomaly. It’s a warning against the neoliberal tendency to see the financial market as some incontrovertible system that can be controlled and managed.

6. President Bashar al-Assad’s favourite band is the Electric Light Orchestra…

BBC

BBC

…apparently. Make of that what you will.

Adam Curtis’s HyperNormalisation is available to watch on iPlayer now.