Roddy Doyle is one of Ireland's best-loved writers, the success of his Barrytown Trilogy and the film adaptation of The Commitments brought Irishness to the global stage in an unprecedented manner. For more than three decades now, his fiction, non-fiction and works for stage and screen have continued to delight and inspire.

Below, Roddy talks about his life, career and inspirations...

The recent stage adaptation of The Snapper was a great success, what was it like revisiting the material in such a hands-on way, considering the novel was originally published in 1990?

Re-opening The Snapper was a strange experience after so long. I hadn’t watched the film since it came out in 1993 or read the book since it was published, so I was able to read it almost as if it had been written by someone else. It didn’t bring back memories; I wasn’t gazing out the window or into the fire. I was immediately reading, and enjoying it, as a piece of work to be done – what would work onstage; what, if anything, was missing; what characters to include or exclude, etc... And the play, from the first day of rehearsal to the last preview, was a terrific, very invigorating experience.

You wrote the screenplay for the 2019 film Rosie which deals with homelessness. How did you research this project, and was it a difficult subject to tackle?

I did no formal research when I started the script, and very little as I wrote. I heard a woman on Morning Ireland describing how she’d spent the day before, looking for somewhere for her family to stay that night. She’d been doing this, daily, for weeks, since they’d had to vacate the house they – her and her partner – had been renting for seven years. She had five children and described trying to get them to school on time, from a different direction, every morning. She was trying to find a new home but spent all day looking for somewhere just for the night. One thing, in particular, gave me pause: her partner couldn’t help because he had to go to work. As I listened, I felt I was listening to a complete story: a woman’s day, her search for a home, even somewhere for the night. Herself and her partner fulfil the social contract: they raise their family, they work for their living. But it’s no longer enough. I started the script that morning. I wrote it very quickly.

How does writing for screen or stage compare to novel writing?

A story is a story, whether on the page or stage, but the writing – the priorities, the craft – is very different. Much of stage writing is instructions to other people – director, actors, designers – and practical decisions– if these two are speaking over here what are the other three doing over there? A novel, on the other hand, is all words; there are no designers and actors to do the work. Every word is a literary decision. A good film script is the foundation for a world; other people will build on top of it. A novel is its entire world.

You regularly post on your Facebook page in the Two Pints format commenting on current events. Are there any topics which you would not discuss in this format? What criteria do you use for deciding what to post?

In theory, there’s nothing – no topic - I wouldn’t get the two men at the bar to talk about. Often, I hear something on the radio, say, and I say to myself, 'I’ll do a Two Pints on that’, but I don’t get around to it – because I’m cooking the dinner and forget or I’m writing something else and forget, or I can’t come up with something to get the two lads chatting. I haven’t written anything on the coronavirus, not because it would be tasteless, but because I haven’t thought of anything worth writing – yet – because it hasn’t been a priority. Death – not mine, though - seems to be quite inspiring.

Your last novel Smile was quite a stylistic departure, one reviewer called it ‘the least Roddyesque of Doyle’s work’. Can we expect your new one, Love (to be published in May) to be a similar departure?

I try to make each new book different, somehow. At this stage of my life, I’d hate to read back something I’ve just written and think, ‘I’ve done that before’, or ‘I’ve told a story very like that before.’ It would seem like a defeat – and a waste. So, yes, Love will be different or, in the language of air travel, a ‘departure’. But, essentially, it’s about two men drinking together and talking. So, I haven’t started writing science fiction.

The success of the Barrytown Trilogy of books and the film adaptation of The Commitments brought Ireland to the international stage in a way it hadn’t been before. Did you feel a weight of responsibility being the person who shaped the perception of Ireland for so many?

All I’ve ever been interested in, really, is writing in a way, or a style, that seems fresh and different and captures, somehow, the place that the characters occupy, Dublin. The Commitments was self-published, so I had no idea that, four years later, there’d be a film based on the book or that it would be a popular and lingering hit. When I wrote it, as I wrote, I wanted to present the story, the characters, the place, in the most direct way, the bluntest, clearest way I thought possible. It was just me and the page. I’ve never felt any other responsibility. I try to write as well I can; that’s all. I’ve been told more than once that The Snapper might encourage young women to consume alcohol while pregnant. Presumably, Two Pints encourages old men to consume alcohol whether they’re pregnant or not.

How did having such success at this early stage impact your career?

It allowed me to work at my own pace and to write exactly what I wanted to write. One foreign-language publisher told me that writing The Woman Who Walked into Doors was a terrible decision, so soon after the success of Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, because nobody would want to read that ‘depressing s**t’. Luckily, hers wasn’t a typical voice, but I could easily ignore it anyway. So, I think the early success made remaining independent that bit easier. And I don’t think I tried to replicate the success, or the formula. Just as well: I love the fact that The Snapper is so much loved in this country, almost public property; but, really, I don’t know why it is.

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

You have an ability to write characters which readers form firm attachments to, whether it’s Paula Spencer, Paddy Clarke, Charlie Savage or others. Which of your characters are you most fond of and why?

Paula Spencer is my favourite character, because she was the most difficult to achieve and she’s one of the few I remain curious about after I’d finished writing about her – twice. I’ve been asked what the rest of Paddy Clarke’s life was like, how he’s getting on in his late-middle years. I haven’t a clue and couldn’t care less; he’s a fictional character, like the others, with no existence off the page. With Paula, though, it’s different. I wonder – a bit.

How did winning the Booker affect your writing?

I’m not sure if, or that, it did. I was writing The Woman Who Walked Into Doors when I won the Booker, and I continued to do that, followed by A Star Called Henry. They are both very unlike Paddy Clarke and the earlier Barrytown novels. It was great winning the Booker but it was a bit of a distraction. It kept me away from work for a while. But I soon copped on – I hope – and got back to my desk.

Watch: Roddy on The Tommy Tiernan Show on RTÉ One

We need your consent to load this YouTube contentWe use YouTube to manage extra content that can set cookies on your device and collect data about your activity. Please review their details and accept them to load the content.Manage Preferences

What is your typical writing day?

I’d love to invent something, to tell you that I climb into the brown wheelie bin in my front garden with my laptop every evening and write in there till dawn, so I can feel close to the urban sounds – the fights, the foxes, the sirens, the rows, the love-making, the vomiting. But actually, I go to my office at about 9 each morning, Monday to Friday, and write till late afternoon. I’m not as tied to the clock since my children grew up but I’m still very disciplined. I tend to work on two projects, say, a novel and a play.

Who are the writers who inspire you and why?

Charles Dickens, because his books are so vivid and lively. I’ve been reading and re-reading his books since I was a child. They change as I get older. I didn’t like Hard Times when I was a young man; I read it again recently and it’s wonderful. Any good book or play gives me the itch to write. Flann O’Brien’s At Swim-Two-Birds was a big book for me; I saw the Dublin accent on the page for the first time when I was sixteen. Sean O’Casey was another big figure. E.L. Doctorow’s novel, Ragtime – the simplicity of the language – persuaded me to think that I could write if I wanted to.

What do you think your character Henry Smart would make of the election result?

If Henry had been watching the election count, he’d have put the telly on pause at about midnight, and he – like many other people throughout the country – would have said, ‘What the f**k is going on?’ He’d be 120 years of age if he was alive and real, but he’d be a bit gleeful.

What can people expect at your forthcoming National Concert Hall date?

I promise to be there on time and I’ll try to make sure I’ve a clean shirt for the evening. I won’t be singing but I’ll be doing a lot of talking.

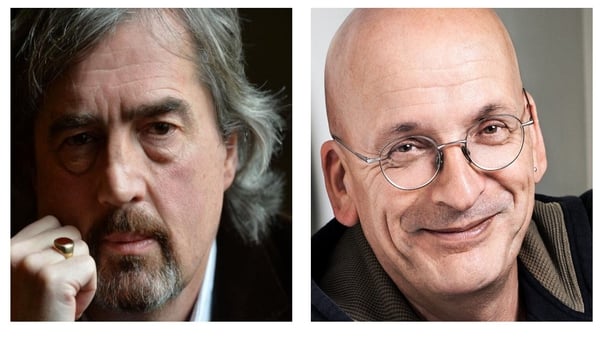

Roddy Doyle's In Conversation with Blindboy at the National Concert Hall, Dublin, on March 25th has been postponed until a later date - stay tuned to RTÉ Culture for updates.