Photo: Jorge Quiñoa

Gary Louris

news

Gary Louris Of The Jayhawks On Barely Listening To Roots Rock & His First Solo Album In 13 Years, 'Jump For Joy'

Gary Louris' songs for the Jayhawks are an intriguing mishmash of styles, including Americana, sunshine-pop and experimental rock. But on his new solo album, 'Jump For Joy,' those influences shine bolder and brighter—and reveal more jagged edges

Next time you watch an artist's press cycle roll out, know this: In many instances, they're sick of the record before it's time to promote it. "I certainly have gone through periods of 'I hate this. I don't even want to put it out,'" Gary Louris tells GRAMMY.com over the phone from Hamilton, Ontario. "Or, 'I absolutely love this.'" Back in 2020, with his band the Jayhawks' album XOXO taking priority, Louris waited—and waited—to put out his solo record, Jump for Joy, as well.

While this may seem like a recipe for hating your own creation, the 66-year-old kept Jump for Joy at something of a distance, not overthinking or smothering it. As a result, Louris is elated to put out a record that feels refreshingly weird and untouched yet with his fingerprints all over it. "In this case, it's worked because of COVID and I'm excited to have something I like coming out," he adds. "And I've also made the decision that I'm not going to wait for the record company anymore."

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//R54IpVpxHT4' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Jump for Joy, which arrived June 4 on Sham/Thirty Tigers, is Louris' first solo album in 13 years. (He last released Vagabonds in 2008.) But while enjoying the intimate, homespun pop songs within, like "New Normal," "Mr. Updike" and "Follow," know that you're not going to have to wait two-and-a-half presidential terms for the next one. A newlywed hitting a new seam of creativity, Louris plans to keep self-producing songs and putting out the results on his website and Bandcamp.

The new album isn't the only thing on Louris' docket: He's been covering the Beatles' White Album in full on his Patreon page; goofing off with his son, Henry, on his music-filled YouTube show, "The S**t Show"; and jamming wild prog records like Yes' Tales from Topographic Oceans. The interior feeling of Jump for Joy sums him up right now: Touring and hitting the studio may not be big priorities, but he's got a wellspring of ideas percolating inside.

GRAMMY.com gave Gary Louris a ring to discuss the long gestation of Jump for Joy, why the next one won't take so long, and which song on the album stemmed from a rejected AT&T jingle.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Gary Louris | Photo: Tim Geaney

While listening to this album, I didn't have a single thought of, "That song sounds like Hollywood Town Hall" or "That part sounds like Tomorrow the Green Grass." I just thought, "That sounds like the Kinks. That sounds like Yes." Is there a faction of your fan base that just wants you to make those two records over and over?

There's definitely a schism we created when we did Smile, even Sound of Lies a little bit. Some people abandoned ship. They didn't like it. Bob Ezrin produced Smile, and I remember that he kept telling me, "Gary, you don't have to be reverential to your audience. Lead, don't follow them."

I grew up listening to pop music and prog rock. Everything English was what I listened to. I didn't grow up in South Carolina listening to Appalachian music. I didn't have brothers or parents who played Crosby, Stills and Nash records. I fell in love with British music. I wanted to be British. I wanted to be in the Who or the Kinks or the Beatles. And then prog rock, hard rock, English punk rock, everything.

I didn't really discover Americana until the '80s. I was like, "This is new, this is cool. I'm not British, and I can take certain things—the soulfulness of that." But underlying everything is always a big, heady dose of British music. English, Anglophile prog and pop, for me. That's what I listen to more than [anything]. I don't listen to roots rock much.

While watching your cover songs on "The S**t Show" and checking out your White Album project, I was thinking that you have a versatile voice, one that can handle all those different songbooks and canons. Where do you want to go with the canon in the future?

Well, it's funny. As you called, I was uploading my latest White Album song I did today to my Patreon page. I did "I'm So Tired."

Originally, I thought, "I want to do something where [it's not] my own music." So I picked the White Album because it's one of my favorites. I recently thought, "Why didn't I do something like Yes' Tales from Topographic Oceans or something really bizarre?" I'll tell you why: Because people would think it's a pompous and difficult prog-rock album to play. But I love that kind of stuff.

My focus is always on writing my own music. However, during the pandemic, I just kind of embraced learning cover songs, which I never really did that much. It teaches you something. It inspires you. And if you're asking what I want to explore as far as covering?

I meant more along the lines of what might infect your own work. Like if you'll make your own super-prog album or British folk album someday.

This is kind of where I ended up, which is kind of prog with a sort of classic pop structure. It still has a sense of American folkiness, which I can't help because I'm American, I guess.

There's always some kind of weird mixture that makes me happy, that seems to balance what I do. And I can do things that I don't do with the Jayhawks, because not everybody likes exactly what I like in the band. I can't force people to play some synthesizers they don't feel like playing. So, I get to explore a little bit more on my own.

I know "New Normal" is an older recording, and the Jump for Joy press release says the songs span decades. I'm curious, though; do the recordings span decades as well?

That's the only one, although I have other recordings I'm finding. Honestly, I'm ashamed of how long it took me between solo records. Life happened and s**t happened and I still have a band going. I want to put out more, much more often if I'm able. But I'm finding other things I like from the old days. "New Normal" is the only one from 2009 or something like that.

All the rest were recorded in the last two and a half years, but they have been around and finished since 2003. The business being what it was, with the Jayhawks putting out a record, it felt it was better to just wait. And now, I'm kind of glad I did. I grumbled, going like, "I want my record out. It's been sitting here."

But now it's kind of new to me ... Because the Jayhawks aren't really getting together to write in the near future, it's like, "Wow, I have something coming out." I'm learning how to play them again. So, it turned out to be good timing. Almost all the songs were just recorded in a little room.

It's kind of stripped down with a lot of buzzy, fuzzy things going on. Were you inspired by the arrangement palette of any particular record from the past?

No, I just love electronica. If I listen to music, I prefer to listen to something electronic. I listen to a lot of things that are not as song-based as you would think because I'm not thinking about how somebody wrote a song. It's just repetitive, electronic stuff.

I knew I wanted to include that because it's very satisfying for me to program things and get them to be in sync with each other, because most of the music I've made with the band has a soulful sloppiness to it that's fun. But, sometimes, I want to go in the other direction.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//fxqMjljRSpA' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

Something about "Almost Home" makes me feel like it was plucked from your memories. What's going on in that song?

It started as a commercial and then evolved into another commercial. I'm not very good at this commercial work because I write too much of a song, where they really want [something smaller]. And I don't do it very often; it's not something I wholly seek out so much as it comes up once in a while. I think, "Well, nobody's buying records anymore anyway." If I have to write something for a commercial, I'm not going to apologize for it.

I did a song, I think, for AT&T. It was "Almost Home." It's about calling and being far away from home and hearing somebody's voice. I just had that little chorus, and they didn't use it. Years later, it sat around, and a friend of mine who worked for an agency said, "This other company's looking for something." I played him different things and he said, "I love that." I worked on it, and of course, too many people got involved and it got diluted and they didn't use it.

But it always stuck in my head: "This is a really catchy song. I should make it into a real song." Because it didn't have a verse; it was just a little riff-y thing. I decided to write something unusual for me, which is more of a story song—less imagery and muddled. It's an ode to my wife.

How about "Living in Between"?

I like songs that are really simple. I like both—I like songs with 20 parts, too—but writing a song with two or three chords with a verse and chorus that share the same progression, I always find that something to aspire to. There [are] a lot of songs I write that I notice are questioning—the meaning of life or what we're doing here or being in the moment.

That song is certainly a question of why I am the age I am and when somebody asks me what I believe, I'm not sure what I would say. I've been seeking and looking and I still don't know.

What can you tell me about "White Squirrel"?

"White Squirrel" is another song that's three chords, I think. Thematically, it's about people who don't fit in. I think it started when I read about a young trans person feeling trapped inside a body that wasn't their own—getting to know more about trans people and expanding to people who always feel out of place, out of sorts, out of sync, not really comfortable in this world.

I guess it's just saying, "You're not alone," and hoping that might help somebody.

In your public school days, did you feel like the odd man out?

Well, it was a private school. It was an all-male, Jesuit, coat-and-tie thing. I think I certainly had some of that in me, yeah. I think that's why people pick on musicians.

We already touched on "New Normal," and I feel like you've talked about that one a lot, so let's skip over to "Mr. Updike."

I'm just a fan [of John Updike]. He wrote about rich, quotidian events. Everyday, kind of small things. I just fell in love with his writing. I'm currently in touch with the family as I might make a video, which is my favorite thing to do now. I discovered iMovie, and my wife and I are making videos for all these songs.

It's just an ode to the writer's life. The thought that creating an idea from nothing and making it artistically happen makes a lot of things in life pale. It's like a high you chase because it gives you purpose and power and it's something unique you can keep going to.

<style>.embed-container { position: relative; padding-bottom: 56.25%; height: 0; overflow: hidden; max-width: 100%; } .embed-container iframe, .embed-container object, .embed-container embed { position: absolute; top: 0; left: 0; width: 100%; height: 100%; }</style><div class='embed-container'><iframe src='https://www.youtube.com/embed//sJBtTBa_doQ' frameborder='0' allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

What about the song "Follow"?

It's just a straight-up love song. It's become a song for my wife, but I originally wrote it for my niece and her husband as a kind of wedding gift. I played it at their wedding. Then, I rewrote it and it's kind of for my wife and I.

And how about "Too Late the Key"?

That one's a little older. Now, that one's a slightly older recording also. It's another questioning, longing song. "Have I made too many mistakes? Have I made too many wrong turns? Am I broken? Will I be able to walk through that door if it opens again? Or am I just too jaded and broken to be open anymore if there's something going on?"

You play a lot of guitar on "One Way Conversation"!

Yeah, I got a little Steely Dan thing in the little break in the middle. I don't remember the thematic [content]. That became more about production than, "I know what that song's about." I write things a lot where I don't know exactly what they mean.

What can you share about the title track, "Jump for Joy"?

Um … dark. It's got a weird, suicidal kind of [feel]. I like the play on words. Not that I was feeling suicidal, but it's got this juxtaposition of words and delivery, or multiple meanings. It's sung in a dark way, but I'm thinking of something ecstatic.

When you think of jumping for joy, you're all excited, but it's also a phrase, to me, that could allude to suicide. Jumping off a ledge to alleviate the pain and the resulting freedom. I certainly don't encourage that, but it's the hypnotic, underwater, dark beauty.

Then, finally, we have "Dead Man's Burden."

[Proudly, brightly] "Dead Man's Burden" is one of my favorite things I've ever written, and I don't know if anybody else will ever like it. My wife loves it. Not too many people have heard it yet. It's stream of consciousness. I could never write anything like it again. It's the bookend. It's the opposite of what I was talking about earlier—two or three chords. The song has about eight parts and maybe one repeats.

And yet, when I tried to edit it and make it more concise, it didn't work at all. It was like a house of cards. You take one card out and the whole thing falls apart. So, I embraced it, and [it's] just an epic—for me—production with strings. It's got multiple movements. I love it. I have no idea if anyone else will, but it's like, "How did I write that?"

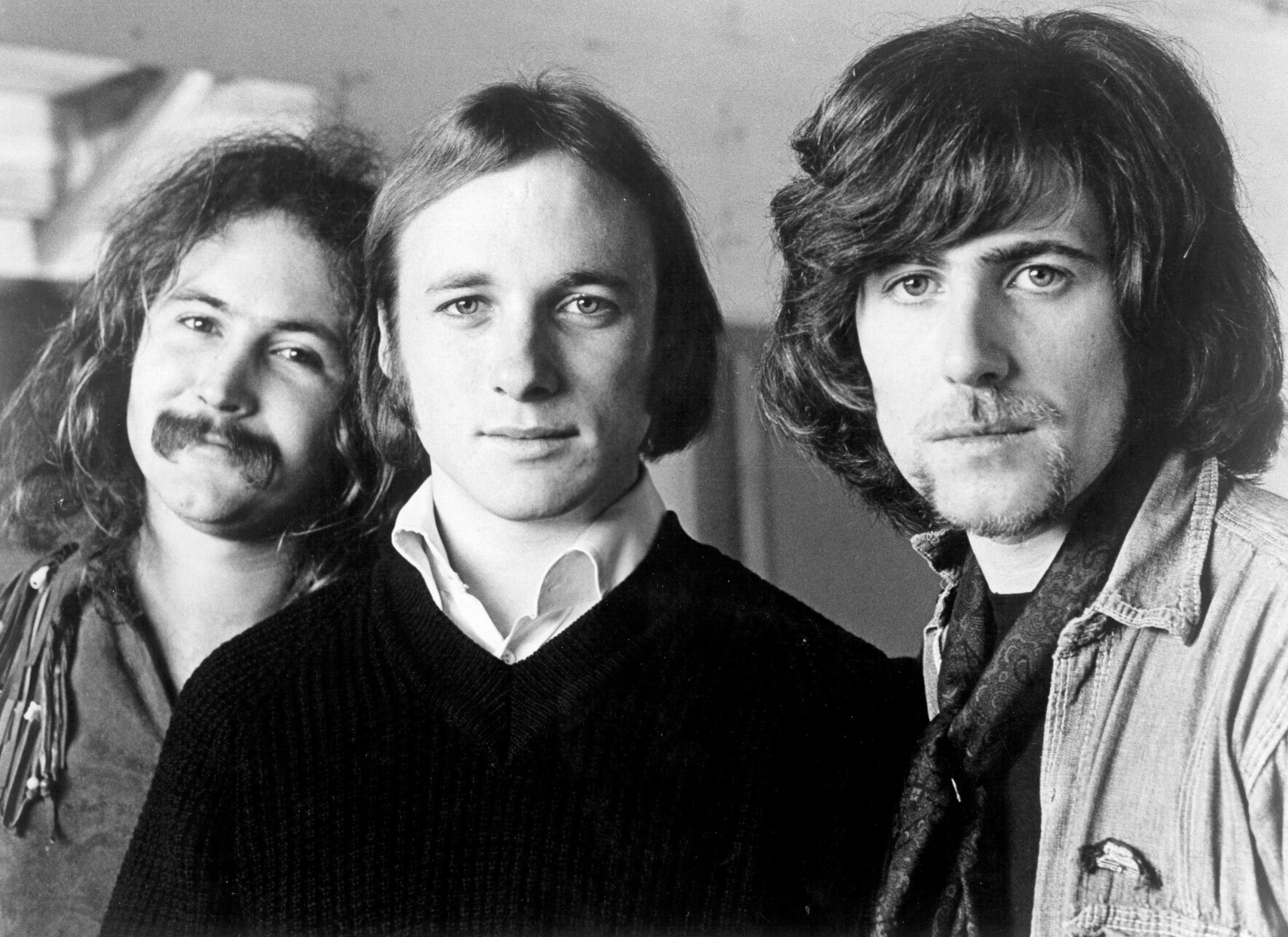

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

5 Things You Didn't Know About 'Crosby, Stills & Nash'

Featuring classics including "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes," "Wooden Ships" and "Helplessly Hoping," Crosby, Stills and Nash's self-titled 1969 debut album is the ultimate entryway to the folk-rock supergroup. Here are five lesser-known facts about its making.

They'd been on ice since 2015, yet the death of David Crosby in 2023 forever broke up one of the greatest supergroups we'll ever know.

Which means Crosby, Stills & Nash's five-decade career is now capped; there's no reunion without that essential, democratic triangle. (Or quadrangle, when Neil Young was involved.) "This group is like juggling four bottles of nitroglycerine," Crosby once quipped. Replied Stephen Stills, "Yeah — if you drop one, everything goes up in smoke."

Looking back on that strange, turbulent, transcendent career, one fact leaps out: there's no better entryway to the group than their 1969 debut, Crosby, Stills & Nash, which turns 55 this year. Not even its gorgeous 1970 follow-up, Déjà Vu — which featured a few songs with one singer and not the others — their sublimation was about to blow apart, leaving shards to fitfully reassemble through the years. (The Stills-Young Band, anyone? How about the Crosby-Nash gigs?)

Pull out your dusty old LP of Crosby Stills & Nash, and look in the eyes of the three artists sitting on a beat-up couch in their s—kickers. The drugs weren't yet unmanageable; any real drama was years, or decades away. Do they see their infamous 1974 "doom tour"? The album cover with hot dogs on the moon? That discordant, Crosby-sabotaged "Silent Night" in front of the Obamas (which happened to be the trio's last public performance)?

At the time of their debut, the three radiated unity, harmony and boundless promise — and classic Crosby, Stills & Nash cuts like "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes" bottled it for our enjoyment forever. Here are five things you may not know about this bona fide folk-rock classic.

There Was Panic Over The Cover Photo

As silly as it seems today — nobody's going to visually mistake Crosby for Stills, or Stills for Nash — that the three were photographed out of order prompted a brief fire alarm.

"We were panicked about it: 'How could you have Crosby's name over Graham Nash?'" Ron Stone of the Geffen-Roberts company recalled in David Browne's indispensable book Crosby, Stills, Nash And Young: The Wild, Definitive Saga Of Rock's Definitive Supergroup. (The explanation: it was still in flux whether they were going to be "Stills, Crosby & Nash" instead.)

The trio actually returned to the site of the photograph to reshoot the cover, but by that time, that decrepit old house on Palm Avenue in West Hollywood had been torn down. (It's a parking lot today, in case you'd like to drag a sofa out there.)

It Could Have Been A Double Album

At one point during Crosby, Stills & Nash's gestation, the idea was floated to render it a double album — one acoustic, one electric.

"Stephen was pushing them to do a rock-and-roll record instead of a folk album because he was the electric guy," session drummer Dallas Taylor said, according to Browne's book. "He wanted to play." (Back in the Buffalo Springfield, Stills and Young would engage in string-popping guitar duels on songs like "Bluebird," foreshadowing Young's impending electric workouts with Crazy Horse.)

Happily, the finished product blended both the band's electric and acoustic impulses; rockers like "Long Time Gone" happily snuggled up to acoustic meditations like "Guinnevere" sans friction.

Famous Friends Were Soaking Up The Sessions

As Browne notes, there was a "no outsiders decree" as this exciting triangulation of Buffalo Springfield, Hollies and Byrds members was secretly forged.

But rock royalty was in and out: at one point, Atlantic Records co-founder Ahmet Ertegun rolled up in a limo with an "eerily quiet" Phil Spector. Joni Mitchell, Cass Elliott, and Judy Collins also turned up — and, yes, Judy Collins, Stills' recent ex, was the namesake for the epochal "Suite: Judy Blue Eyes."

"It started out as a long narrative poem about my relationship with Judy Collins," Stills said in 1991. "It poured out of me over many months and filled several notebooks." (The "Thursdays and Saturdays" line refers to her therapy visits. "Stephen didn't like therapy and New York," Collins said in the book, "and I was in both.")

"Long Time Gone" Almost Didn't Make It On The Album

Crosby's probing rocker "Long Time Gone" meant a lot to him. He'd less written than channeled it from the ether, immediately after the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy.

"It wasn't just about Bobby," he told Browne in the book. "He was the penultimate trigger. We lost John Kennedy and Martin Luther King, and then we lost Bobby. It was discouraging, to say the least. The song was very organic. I didn't plan it. It just came out that way."

It was always considered for Crosby, Stills & Nash, but it was proving hard to capture it in the studio. It might have died on the vine had Stills not sent Crosby and Nash home so he could work on the arrangement — which took an all-nighter to get right.

When he played the others his new arrangement, an exhilarated Crosby tossed back wine, and dove into the song "with a new, deeper tone," as Browne puts it — "almost as if he were underwater tone, almost as if he were underwater and struggling for air."

Ertegun Boosted The Voices — And Thank Goodness He Did

For all the prodigious, multilayered talent in Crosby, Stills & Nash, it's their voices that were at the forefront of their art — and should have always been.

However, the original mix had their voices relatively lower in the mix; Ertegun, correctly perceiving that their voices were the main attraction, ordered a remix, and thank goodness he did. The band initially pushed back, but as Stills admitted, "Ahmet signs our paychecks." As they say, the rest is history.

David Crosby On His New Album For Free & Why His Twitter Account Is Actually Joyful

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

list

6 Things We Learned From Disney+'s 'The Beach Boys' Documentary

From Brian Wilson's obsession with "Be My Baby" and the Wall Of Sound, to the group's complicated relationship with Murry Wilson and Dennis Wilson's life in the counterculture, 'The Beach Boys' is rife with insights from the group's first 15 years.

It may seem like there's little sand left to sift through, but a new Disney+ documentary proves that there is an endless summer's worth of Beach Boys stories to uncover.

While the legendary group is so woven into the fabric of American culture that it’s easy to forget just how innovative they were, a recently-released documentary aims to remind. The Beach Boys uses a deft combination of archival footage and contemporary interviews to introduce a new generation of fans to the band.

The documentary focuses narrowly on the first 15 years of the Beach Boys’ career, and emphasizes what a family affair it was. Opening the film is a flurry of comments about "a certain family blend" of voices, comparing the band to "a fellowship," and crediting the band’s success directly to having been a family. The frame is apt, considering that the first lineup consisted of Wilson brothers Brian, Dennis, and Carl, their cousin Mike Love, and high school friend Al Jardine, and their first manager was the Wilsons’ father, Murry.

All surviving band members are interviewed, though a very frail Brian Wilson — who was placed under a conservatorship following the January death of his wife Melinda — appears primarily in archival footage. Additional perspective comes via musicians and producers including Ryan Tedder, Janelle Monáe, Lindsey Buckingham, and Don Was, and USC Vice Provost for the Arts Josh Kun.

Thanks to the film’s tight focus and breadth of interviewees, it includes memorable takeaways for both longtime fans and ones this documentary will create. Read on for five takeaways from Disney+'s The Beach Boys.

Family Is A Double-Edged Sword

For all the warm, tight-knit imagery of the Beach Boys as a family band, there was an awful lot of darkness at the heart of their sunny sound, and most of the responsibility for that lies with Wilson family patriarch Murry Wilson. Having written a few modest hits in the late 1930s, Murry had talent and a good ear, and he considered himself a largely thwarted genius.

When Brian, Dennis, and Carl formed the Beach Boys with their cousin Mike Love and friend Al Jardine, Murry came aboard as the band’s manager. In many respects, he was capable; his dogged work ethic and fierce protectiveness helped shepherd the group to increasingly high profile successes. He masterminded the extended Wilson family call-in campaign to a local radio station, pushing the Beach Boys’ first single "Surfin’" to become the most popular song in Los Angeles. He relentlessly shopped their demos to music labels, eventually landing them a contract at Capitol Records. He supported the band’s strong preference to record at Western Recordings rather than Capitol Records’ own in-house studio, and was an excellent promoter.

Murry Wilson was also extremely controlling, fining the band when they made mistakes or swore, and "was miserable most of the time," according to his wife Audree.

Footage from earlier interviews with Carl and Dennis, and contemporary comments from Mike Love make it clear that Murry was emotionally and physically abusive to his sons throughout their childhoods. He even sold off the Beach Boys’ songwriting catalog without consulting co-owner Brian, a moment that Brian’s ex-wife Marilyn says he felt so keenly that he took to his bed and didn’t get up for three days.

Murry Wilson was at best a very complicated figure, both professionally jealous of his own children to a toxic degree and devoted to ensuring their success.

"Be My Baby" and The Wrecking Crew Changed Brian Wilson’s Life

"Be My Baby," which Phil Spector had produced for the Ronettes in 1963, launched the girl group to immediate iconic status. The song also proved life-changing for Brian. On first hearing the song, "it spoke to my soul," and Brian threw himself into learning how Spector created his massive, lush Wall of Sound. Spector’s approach taught Brian that production was a meaningful art that creates an "overall sound, what [the listeners] are going to hear and experience in two and a half minutes."

By working with The Wrecking Crew — a truly motley bunch of experienced, freewheeling musicians who played on Spector’s records and were over a decade older than the Beach Boys — Brian’s artistic sensibility quickly emerged. According to drummer Hal Blaine and bassist Carol Kaye, Brian not knowing what he didn’t know gave him the freedom and imagination to create sounds that were completely new and innovative.

Friendly Rivalries With Phil Spector & The Beatles Yielded Amazing Pop Music

According to popular myth, the Beach Boys and the Beatles saw each other exclusively as almost bitter rivals for the ears, hearts, and disposable income of their fans. The truth is more nuanced: after the initial shock of the British Invasion wore off, the two groups developed and maintained a very productive, admiration-based competition, each band pushing the other to sonic greatness.

Cultural historian and academic Josh Kun reframes the relationship between the two bands as a "transatlantic collaboration," and asks, "If they hadn’t had each other, would they have become what they became?" Could they have made the historic musical leaps that we now take for granted?

Read more: 10 Memorable Oddities By The Beach Boys: Songs About Root Beer, Raising Babies & Ecological Collapse

The release of Rubber Soul left Brian Wilson thunderstruck. The unexpected sitar on "Norwegian Wood," the increasingly mature, personal songwriting, all of it was so fresh that "I flipped!" and immediately wanted to record "a thematic album, a collection of folk songs."

Brian found life on the road soul-crushing and terrifying, and was much more content to stay home composing, writing, and producing. With the touring band out on the road, and with a creative fire lit under him by both the Beatles and Phil Spector’s Wall of Sound, he had time to develop into a wildly creative, exacting, and celebrated producer, an experience that yielded the 1966 masterpiece, Pet Sounds.

Pet Sounds Took 44 Years To Go Platinum

You read that right: Pet Sounds was a flop in the U.S. upon its release. Even after hearing radio-ready tracks like "Wouldn’t It Be Nice?" and "Sloop John B" and the ravishing "God Only Knows," Capitol Records thought the album had minimal commercial potential and didn’t give it the promotional push the band were expecting. Fans in the United Kingdom embraced it, however, and the votes of confidence from British fans — including Keith Moon, John Lennon, and Paul McCartney — buoyed both sales and the Beach Boys’ spirits.

In fact, Lennon and McCartney credited Pet Sounds with giving them a target to hit when they went into the studio to record the Beatles’ own next sonically groundbreaking album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. As veteran producer and documentary talking head Don Was puts it, Brian Wilson was a true pioneer, incorporating "textures nobody had ever put into pop music before." The friendly rivalry continued as the Beatles realized that they needed to step up their game once more.

Read more: Masterful Remixer Giles Martin On The Beach Boys' 'Pet Sounds,' The Beatles, Paul McCartney

Meanwhile, Capitol Records released and vigorously promoted a best-of album full of the Beach Boys’ early hits, Best Of The Beach Boys. The collection of sun-drenched, peppy tunes was a hit, but was also very out of step with the cultural and political shifts bubbling up through the anti-war and civil rights movements of the era. Thanks in part to later critical re-appraisals and being publicly embraced by musicians as varied as Questlove and Stereolab, Pet Sounds eventually reached platinum status in April 2000, 44 years after its initial release.

Dennis Wilson Was The Only Truly Beachy Beach Boy

Although the Beach Boys first made a name for themselves as purveyors of "the California sound" by singing almost exclusively about beaches, girls, and surfing, the only member of the band who really liked the beach was drummer Dennis Wilson.

Al Jardine ruefully recalls that "the first thing I did was lose my board — I nearly drowned" on a gorgeous day at Manhattan beach. Dennis was an actual surfer whose tanned, blonde good looks and slightly rebellious edge made him the instant sex symbol of the group. In 1967, when Brian’s depression was the deepest and he relinquished in-studio control of the band, Dennis flourished musically and lyrically. Carl Wilson, who had emerged as a very capable producer in Brian’s absence, described Dennis as evolving artistically "really quite amazingly…it just blew us away."

Dennis was also the only Beach Boy who participated meaningfully in the counterculture of the late 1960s, a movement the band largely sat out of, largely to the detriment of their image. He introduced the band to Transcendental Meditation — a practice Mike Love maintains to this day — and was a figure in the Sunset Strip and Laurel Canyon music scenes. Unfortunately, he also became acquainted with and introduced his bandmates to Charles Manson. Manson’s true goal was rock stardom; masterminding the gruesome mass murders that his followers perpetrated in 1969 was a vengeful outgrowth of his thwarted ambition.

The Beach Boys did record and release a reworked version of one of Manson’s songs, "Never Learn Not To Love" as a B-side in 1968. Love says that having introduced Manson to producer Terry Melcher, who firmly rebuffed the would-be musician, "weighed on Dennis pretty heavily," and while Jardine emphatically and truthfully says "it wasn’t his fault," it’s easy to imagine those events driving some of the self-destructive alcohol and drug abuse that marked Dennis’ later years.

The Journey From Obscurity To Perennially Popular Heritage Act

The final minutes of The Beach Boys can be summed up as "if all else fails commercially, release a double album of beloved greatest hits." The 1970s were a very fruitful time for the band creatively, as they invited funk specialists Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar to join the band and relocated to the Netherlands to pursue a harder, more far-out sound. Although the band were proud of the lush, singer/songwriter material they were recording, the albums of this era were sales disappointments and represented a continuing slide into uncoolness and obscurity.

Read more: Brian Wilson Is A Once-In-A-Lifetime Creative Genius. But The Beach Boys Are More Than Just Him.

Once again, Capitol Records turned to the band’s early material to boost sales. The 1974 double-album compilation Endless Summer, comprised of hits from 1962-1965, went triple platinum, relaunching The Beach Boys as a successful heritage touring act. A new generation of fans — "8 to 80," as the band put it — flocked to their bright harmonies and upbeat tempos, as seen in the final moments of the documentary when the Beach Boys played to a crowd of over 500,000 fans on July 4, 1980.

While taking their place as America’s Band didn’t do much to make them cool, it did ensure one more wave of chart success with 1988’s No. 1 hit "Kokomo" and ultimately led to broader appreciation for Pet Sounds and its sibling experimental albums like Smiley Smile. That wave of popularity has proven remarkably durable; after all, they’ve ridden it to a documentary for Disney+ nearly 45 years later.

Listen: 50 Essential Songs By The Beach Boys Ahead Of "A GRAMMY Salute" To America's Band

Photo: Ethan A. Russell / © Apple Corps Ltd

list

5 Lesser Known Facts About The Beatles' 'Let It Be' Era: Watch The Restored 1970 Film

More than five decades after its 1970 release, Michael Lindsay-Hogg's 'Let it Be' film is restored and re-released on Disney+. With a little help from the director himself, here are some less-trodden tidbits from this much-debated film and its album era.

What is about the Beatles' Let it Be sessions that continues to bedevil diehards?

Even after their aperture was tremendously widened with Get Back — Peter Jackson's three-part, almost eight hour, 2021 doc — something's always been missing. Because it was meant as a corrective to a film that, well, most of us haven't seen in a long time — if at all.

That's Let it Be, the original 1970 documentary on those contested, pivotal, hot-and-cold sessions, directed by Michael Lindsay-Hogg. Much of the calcified lore around the Beatles' last stand comes not from the film itself, but what we think is in the film.

Let it Be does contain a couple of emotionally charged moments between maturing Beatles. The most famous one: George Harrison getting snippy with Paul McCartney over a guitar part, which might just be the most blown-out-of-proportion squabble in rock history.

But superfans smelled blood in the water: the film had to be a locus for the Beatles' untimely demise. To which the film's director, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, might say: did we see the same movie?

"Looking back from history's vantage point, it seems like everybody drank the bad batch of Kool-Aid," he tells GRAMMY.com. Lindsay-Hogg had just appeared at an NYC screening, and seemed as surprised by it as the fans: "Because the opinion that was first formed about the movie, you could not form on the actual movie we saw the other night."

He's correct. If you saw Get Back, Lindsay-Hogg is the babyfaced, cigar-puffing auteur seen throughout; today, at 84, his original vision has been reclaimed. On May 8, Disney+ unveiled a restored and refreshed version of the Let it Be film — a historical counterweight to Get Back. Temperamentally, though, it's right on the same wavelength, which is bound to surprise some Fabs disciples.

With the benefit of Peter Jackson's sound-polishing magic and Giles Martin's inspired remixes of performances, Let it Be offers a quieter, more muted, more atmospheric take on these sessions. (Think fewer goofy antics, and more tight, lingering shots of four of rock's most evocative faces.)

As you absorb the long-on-ice Let it Be, here are some lesser-known facts about this film, and the era of the Beatles it captures — with a little help from Lindsay-Hogg himself.

The Beatles Were Happy With The Let It Be Film

After Lindsay-Hogg showed the Beatles the final rough cut, he says they all went out to a jovial meal and drinks: "Nice food, collegial, pleasant, witty conversation, nice wine."

Afterward, they went downstairs to a discotheque for nightcaps. "Paul said he thought Let it Be was good. We'd all done a good job," Lindsay-Hogg remembers. "And Ringo and [wife] Maureen were jiving to the music until two in the morning."

"They had a really, really good time," he adds. "And you can see like [in the film], on their faces, their interactions — it was like it always was."

About "That" Fight: Neither Paul Nor George Made A Big Deal

At this point, Beatles fanatics can recite this Harrison-in-a-snit quote to McCartney: "I'll play, you know, whatever you want me to play, or I won't play at all if you don't want me to play. Whatever it is that will please you… I'll do it." (Yes, that's widely viewed among fans as a tremendous deal.)

If this was such a fissure, why did McCartney and Harrison allow it in the film? After all, they had say in the final cut, like the other Beatles.

"Nothing was going to be in the picture that they didn't want," Lindsay-Hogg asserts. "They never commented on that. They took that exchange as like many other exchanges they'd had over the years… but, of course, since they'd broken up a month before [the film's release], everyone was looking for little bits of sharp metal on the sand to think why they'd broken up."

About Ringo's "Not A Lot Of Joy" Comment…

Recently, Ringo Starr opined that there was "not a lot of joy" in the Let it Be film; Lindsay-Hogg says Starr framed it to him as "no joy."

Of course, that's Starr's prerogative. But it's not quite borne out by what we see — especially that merry scene where he and Harrison work out an early draft of Abbey Road's "Octopus's Garden."

"And Ringo's a combination of so pleased to be working on the song, pleased to be working with his friend, glad for the input," Lindsay-Hogg says. "He's a wonderful guy. I mean, he can think what he wants and I will always have greater affection for him.

"Let's see if he changes his mind by the time he's 100," he added mirthfully.

Lindsay-Hogg Thought It'd Never Be Released Again

"I went through many years of thinking, It's not going to come out," Lindsay-Hogg says. In this regard, he characterizes 25 or 30 years of his life as "solitary confinement," although he was "pushing for it, and educating for it."

"Then, suddenly, the sun comes out" — which may be thanks to Peter Jackson, and renewed interest via Get Back. "And someone opens the cell door, and Let it Be walks out."

Nobody Asked Him What The Sessions Were Like

All four Beatles, and many of their associates, have spoken their piece on Let it Be sessions — and journalists, authors, documentarians, and fans all have their own slant on them.

But what was this time like from Lindsay-Hogg's perspective? Incredibly, nobody ever thought to check. "You asked the one question which no one has asked," he says. "No one."

So, give us the vibe check. Were the Let it Be sessions ever remotely as tense as they've been described, since man landed on the moon? And to that, Lindsay-Hogg's response is a chuckle, and a resounding, "No, no, no."

Photo: Lionel Hahn/Getty Images

interview

Catching Up With Sean Ono Lennon: His New Album 'Asterisms,' 'War Is Over!' Short & Shouting Out Yoko At The Oscars

Sean Ono Lennon is having a busy year, complete with a new instrumental album, 'Asterisms,' and an Oscar-winning short film, 'War is Over!' The multidisciplinary artist discusses his multitude of creative processes.

Marketing himself as a solo musician is a little excruciating for Sean Ono Lennon. It might be for you, too, if you had globally renowned parents. Despite his musical triumphs over the years, Lennon is reticent to join the solo artist racket.

Which made a certain moment at the 2024 Oscars absolutely floor him: Someone walked up to Lennon and told him "Dead Meat," from his last solo album, 2006's Friendly Fire, was his favorite song ever. Not just on the album, or by Lennon. Ever.

"I was so shocked. I wanted to say something nice to him, because it was so amazing for someone to say that," Lennon tells GRAMMY.com. "But it was too late anyway." (Thankfully, after he tweeted about that out-of-nowhere moment, the complimenter connected with him.)

It's a nice glimmer of past Lennon, one who straightforwardly walked in his father's shoes. But what's transpired since 2006 is far more interesting than any Beatle mini-me.

Creatively, Lennon has a million irons in the fire — with the bands the Ghost of a Saber Tooth Tiger, the Claypool Lennon Delirium, his mom's Plastic Ono Band, and beyond.

And in 2024, two projects have taken center stage. In February, he delivered his album Asterisms, a genreless instrumental project with a murderer's row of musicians in John Zorn's orbit, released on Zorn's storied experimental label Tzadik Records. Then just a few weeks later, his 2023 short film War is Over! — for which he co-wrote the original story, and is inspired by John Lennon and Yoko Ono's timeless peace anthem "Happy Xmas (War Is Over)" — won an Oscar for Best Animated Short Film.

On the heels of the latter, Lennon sat down with GRAMMY.com to offer insights on both projects, and how they each contributed to "really exciting" creative liberation.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

You shouted out your mom at the Oscars a couple of months back. How'd that feel?

Well, honestly, it felt really cosmic that it was Mother's Day [in the UK]. So I just kind of presented as a gift to her. It felt really good. It felt like the stars were aligning in many ways, because she was watching. It was a very sweet moment for me.

What was the extent of your involvement with the War Is Over! short?

Universal Music had talked to me about maybe coming up with a music video idea. I had been trying to develop a music video for a while, and I didn't like any of the concepts; it just felt boring to me.

The idea of watching a song that everyone listens to already, every year, with some new visual accompaniment — it didn't feel that interesting. So, I thought it'd be better to do a short film that kind of exemplifies the meaning of the song, because then, it would be something new and interesting to watch.

That's when I called my friend Adam Gates, who works at Pixar. I was asking him if he had any ideas for animators, or whatever. I knew Adam because he had a band called Beanpole. [All My Kin] was a record he made years ago with his friends, and never came out. It's this incredible record, so I actually put it out on my label, Chimera Music.

But Adam couldn't really help me with the film, because he's still contractually with Pixar, and they have a lot of work to do. But he introduced me to his friend Dave Mullins, who's the director. He had just left Pixar to start a new production company. He could do it, because he was independent, freelance.

Dave and I had a meeting. In that first meeting, we were bouncing around ideas, and we came up with the concept for the chess game and the pigeon. I wanted it to be a pigeon, because I really love pigeons, and birds. We wrote it together, and then we started working on it.

So, I was there from before that existed, and I saw the thing through as well. I also brought in Peter Jackson to do the graphics.

This message unfortunately resonates more than ever. Republicans used to be the war hawks; now, it's Democrats. What a reversal.

It just feels like we live in an upside-down world. Something happened where we went through a wormhole, and we're in this alternate reality. I don't know how it happened. But it's not the only [example]; a lot of things just seem absolutely absurd with the world these days.

But hopefully, it points toward something better. I try to be optimistic. In the Hegelian dialectic, you have to have a thesis and antithesis, and the synthesis is when they fuse to become a better idea. So, I'm hoping that all the tension in society right now is what the final stage of synthesis looks like.

How'd the filmmaking process roll on from there?

Dave had made a really great short film called LOU when he was at Pixar; that was also nominated for an Oscar. He and [producer] Brad [Booker] know a ton of talented people; they have an amazing character designer.

We started sending files back and forth with WingNut in New Zealand; they would be adding the skins to the characters.

One of the first stages was the performance capture, where you basically attach a bunch of ping pong balls to a catsuit and a bicycle helmet. You record the position of these ping pong balls in a three-dimensional space. That gives you the performance that you map the skins onto on the computer later on.

For a couple of years, there was a lot of production. David and his team did a really good job of inventing and designing uniforms for the imaginary armies that never existed, because we really didn't want to identify any army as French or British or German or anything.

We wanted to get a kind of parallel universe — an abstraction of the First World War. We designed it so that one army was based on round geometry, and the other was based on angular geometry.

It was a long process, and it was really fun. I learned a lot about modern computer animation.

Between Em Cooper's GRAMMY-winning "I'm Only Sleeping" video and now this, the Beatles' presence in visual media is expanding outward in a cool way.

I think we've been really fortunate to have a lot of really great projects to give to the world. I've only been working on the Beatles and John Lennon stuff directly in the last couple of years, and it's been really exciting for me.

And a big challenge, obviously, because I don't [hesitates] want to f— up. [Laughs.] But it's been a real honor. And I'm very grateful to my mom for giving me the freedom to try all these wacky ideas. Because a lot of people are like, "Oh, when are you going to stop trying to rehash the past with the Beatles, or John Lennon?"

Because the modern world is as it is, I feel like we have a responsibility to try to make sure that the Beatles and John Lennon's music remains out there in the public consciousness, because I think it's really important. I think the world needs to remember the Beatles' music, and remember John and Yoko. It's really about making sure we don't get lost in the white noise of modernity.

I love Asterisms. Where are you at in your journey as a guitarist? I'm sure you unlocked something here.

Like it's a video game. It's weird — I don't even consider myself a guitar player. I'm just, like, a software. But I think it's more about confidence — because it's really hard for me to get over my insecurity with playing and stuff.

For so many different reasons, it's probably just the way I'm designed — being John and Yoko's kid, growing up with a lot of preconceived notions or expectations about me, musically.

So, it's always been hard to accept myself as a musician, and this was kind of a lesson in getting over myself. Accepting what I wanted to play, and just doing it.

This is my Tzadik record, so it had to be all these fancy, amazing musicians. It doesn't matter what your chops are: it's more about how you feel, and the feeling you bring to your performance.

Once we recorded, it sounded amazing, because we recorded live to tape. So, everything on that album is live, except for my guitar solos. I didn't play my solos live, because I had to play the rhythm guitar. I was just paying attention to the band and cueing people. Once we finished the basic tracks, it just took us a couple of days, and it was done.

It was the simplest record I've ever done, because there were no vocals, so there wasn't a lot of mixing process. We recorded live to 16-track tape, and it was done.

I caught wind a couple of years back that you were working on another solo record simultaneously. Is that true?

I was working on a solo record of songs with lyrics. I finished it, and — I don't know, I think this speaks to the mental problems I have — but I didn't like it suddenly, and i never put it out. I just felt weird about it. I think I overthought it or something.

Then Zorn asked me to do an instrumental thing, and it was a no-brainer, because I've been a fan my whole life. The idea of getting to do something on his label was really an honor.

I got turned on to so many amazing musicians from Zorn, like Joey Baron, Dave Douglas, Kenny Wolleson, and Marc Ribot. Growing up in New York, that's always been my idea of where the greatest musicians are — Zorn and his gang.

Why'd you feel weird about the other album? Did it just not have the juice?

It's not that I didn't think it had the juice. I just got uncomfortable with the idea of putting out a solo record, and the whole process. I got nervous. I still think it's good. But I don't know if it's good enough to warrant me releasing it.

That's fine playing in bands, like the [Claypool Lennon] Delirium and GOASTT [Ghost of a Saber Toothed Tiger]. It takes a degree of unnecessary pressure off of making music. But as soon as your actual birth name is on the record, it starts to feel uncomfortable for me.

People are ruthless today, period. But they're especially critical of me with music. So, it's like, Do I really need to do that s—? It's a little more awkward: "I, myself, Sean Lennon, am putting out my art, and here it is." I'd rather be part of the band.