17 min read

This article is more than 6 years old

Feature

Residents in ‘someone else’s land’: How interaction with Indigenous Australians gave new meaning to these migrants’ lives

Four migrants, one story: Finding their identity and sense of place in Australia, whilst being wedged between two worlds.

Published 24 March 2018 8:42am

By Claudianna Blanco

Four migrants, one story: Wedged between two worlds

When Clinton Pryor kneeled to kiss the ground in front of the sacred fire at the Tent Embassy in Canberra, the world was finally paying attention.

Clinton’s Walk for Justice had started in Perth, Western Australia, 12 months, some 6000 kilometres and eight pairs of shoes earlier. He had embarked on a journey collecting messages from disadvantaged Indigenous communities around the country, with the aim to take their plight to the Australian capital and call for change. But, until that moment, the world, and most Australians were largely unaware of Clinton Pryor. There had been little mainstream media coverage, leaving his fans to follow his journey through social media. Alfred Pek, a recent media graduate originally from Indonesia, came across the story by chance.

But, until that moment, the world, and most Australians were largely unaware of Clinton Pryor. There had been little mainstream media coverage, leaving his fans to follow his journey through social media. Alfred Pek, a recent media graduate originally from Indonesia, came across the story by chance.

Clinton Pryor sitting in front of the sacred fire at the Tent Embasssy, Canberra. Credit: Alfred Pek. Source: Supplied/Alfred Pek

“When I first heard about it, I didn’t really grasp truly the extent of what he (Clinton) was actually doing, because all I knew is that there was this Aboriginal man walking from Perth to Canberra,” Alfred tells me.

“It’s actually really amazing how anyone, in general, would do that … but when I looked at the stories and what he (Clinton) was trying to do, it actually got really interesting in terms of what he was trying to achieve."

Alfred, who settled in Australia in 2007 at age 13, first heard about Clinton when he was at the Tent Embassy in Canberra in late 2016, covering a story about father and son duo, Adam Richards and Ned Thorn, who walked from Adelaide to Canberra to petitioning for the closure of detention centres.

“I thought, well this actually would be a very good introduction for a lot of people as well, especially for those of us who may not be exposed to it (Indigenous issues) in the first place.

Recording Clinton’s walk for a potential documentary was Alfred’s entry point to Indigenous Australians and their cultures. He offered Clinton and his crew media training. He produced a few videos and used his connections to help spread the story internationally.

“What motivated me, I think, it’s really the fact that he was doing something simple, yet something that’s really powerful,” Alfred says. With time, he forged strong friendships with Clinton’s support team, and in doing so, unlocked a deeper understanding of his new country’s Indigenous history and heritage – and a new appreciation of how he, as a migrant, fits into the fabric of Australian society.

With time, he forged strong friendships with Clinton’s support team, and in doing so, unlocked a deeper understanding of his new country’s Indigenous history and heritage – and a new appreciation of how he, as a migrant, fits into the fabric of Australian society.

Alfred Pek with Clinton Pryor and his support crew. Credit: Andy Dries. Source: Supplied/Andy Dries.

“I came to Australia as an immigrant, and Australia accepted me and I eventually became a citizen in 2012,” he says.

“We have a changing demographic and there’ll be a lot more migrants in Australia, and that’s just a fact, that’s how the future will be. But what’s important for us to realise as migrants first, is the fact that the history of Australia is much more than the colonial British or European history that it has been founded upon, at least as a concept. There is history before it became Australia.

“[There were] all of these rainbow nations, cultures and languages out there that we are not exposed to, and I wasn’t exposed to until I really went out of my way to look into that,” Alfred says.

Alfred admits if he had not ventured “out of his comfort zone” to establish a significant connection with Indigenous Australians, he would’ve missed out on learning about what makes this country unique. Likewise, he says he wouldn't have realized that as a new Australian, whilst he’s detached from the country’s colonial past, he still benefits from it.

“Just because we don’t have the historical colonial context as an immigrant to Australia, we’re still a group of people that benefit from the systems that oppress a lot of these Indigenous cultures.

“We have to truly acknowledge that,” he adds. For me, as a Venezuelan-born migrant, Alfred’s observations resonate with my own experiences.

For me, as a Venezuelan-born migrant, Alfred’s observations resonate with my own experiences.

Alfred Pek and Clinton Pryor in Melbourne. Credit: Christina Coombe Source: Supplied/Christina Coombe

When I first moved to Sydney after having lived in Japan for seven years, I felt there was a gaping hole in my life. You see, in Tokyo, one of the world’s most technologically advanced megalopolises, ancient traditions still stand between the skyscrapers. As a foreign resident, learning about the culture, speaking the language and participating in ritual was not only interesting, it was expected of me. This was initially missing from my new life in Australia.

One sunny Sydney morning, the sudden realisation that I was in the land of the world’s oldest continuing culture, came to me like a lightning bolt. Why was Aboriginal culture so invisible? So absent from our everyday life? I was determined to find out more about Indigenous Australians, but it wasn’t easy.

Internet searches yielded tertiary Indigenous studies and a few Indigenous bush tucker tours. But I wasn’t interested in a degree or a discounted package deal. I approached my Indigenous colleagues in the newsroom, who suggested I visit the Redfern Community Centre; but as a new migrant, I didn’t understand what that meant, so I didn’t follow their advice… At the time, I didn’t even think to ask them about their Aboriginality, maybe because as a Latin-American from an ethnically diverse country, where many of us are a blend of Indigenous, European and African, I didn’t see my Aboriginal colleagues as ‘different’.

So five years later, when the opportunity to live and work in a remote community in Central Australia came up, I jumped at the chance. Surely, by going there, I would meet ‘real Aboriginal people’, I naively thought back then.

My time spent with Anangu Traditional Owners was so absolutely foreign, yet so immediately comfortable. I felt truly welcomed. No one asked me, ‘where are you from?’ when they first met me. My place of origin wasn’t a determining factor in our relationship; there was no need to point out that I wasn’t an ‘Aussie’. Instead, I was encouraged to sit around the campfire, observe, learn how to make a good cuppa and listen, listen, listen to the senior ladies. Every time I did something for Anangu, I would get something in return, and every time they did something for me, I was expected to give something back — ngapartji-ngapartji (give-give or share-share in Pitjantjatjara), “that’s how you work the right way”, I was told.

Every time I did something for Anangu, I would get something in return, and every time they did something for me, I was expected to give something back — ngapartji-ngapartji (give-give or share-share in Pitjantjatjara), “that’s how you work the right way”, I was told.

Source: Supplied/Claudianna Blanco

It wasn’t all hunky dory, of course. There were many misunderstandings, frustrations and a few scary moments, but that that was part of the deal. There was disadvantage, cheekiness and humbug. I saw poverty, domestic violence, incarceration, suicide and depression, but there were also incredible bush trips, humour, resilience and generosity.

I met many other desert-dwelling white fellas from the city. Some had gone bush to escape their pasts, others came as ‘do-gooders’, wanting to lend a helping hand. While the nobility of their intentions seemed appreciated, they were not always welcomed. I was told that wasn’t “the right way”. I too fell in the ‘saviour’ trap more than once, where you try to ‘help’ without engaging instead, and got rightly scolded when I did by those who cared.

I don’t think I’ll ever fully learn how to really listen, but what I did learn was the importance of language, culture and land for Anangu, and how their priorities were different to mine. For them, keeping Tjukurpa (traditional law and lore) strong, despite constant external pressure to ‘assimilate’, abject destitution and the aftermath of colonisation, frequently outweighed the western ideals of social status and financial gain.

Israeli-born linguist and language revivalist Ghil’ad Zuckermann is another migrant working on the frontline of alleviating the impacts of Australia’s colonial past. Based at Adelaide University, Professor Zuckermann moved here driven by the myth of the ‘lucky country’. But his perception quickly changed, as he learnt more about Australia’s relationship with its Indigenous peoples.

“When I arrived, I thought to myself … what can I give to Australia? … If somebody is hosting me nicely, I need to pay my dues back to the local society,” he recalls.

“I should help with the Aboriginal fight,” he said to himself.

“Had I been a dentist, I would have given them teeth… Had I been a psychologist, I would have got my Aboriginal friends out of smoking… But I’m a linguist.”

“I decided that because my expertise is ‘revitalistics’, what I need to do is to assist Aboriginal people with reconnecting with their heritage through language,” he says.

Professor Zuckermann’s desire to contribute meaningfully as a migrant took him down the path of reviving Barngarla, an Aboriginal language widely spoken in the Eyre Peninsula in South Australia until the 1960s. It almost disappeared with the Stolen Generations.

“The English colonisers consciously wiped out these languages, in a process that I call ‘linguicide’ – language killing.” “Linguicide is, in my opinion, a loss of the soul,” he says.

When Professor Zuckermann offered Traditional Owners to jointly revive their language, they grabbed the opportunity with two hands.

“They told me, ‘we’ve been waiting for you for 50 years’,” he says. For him, it was paramount that the owners of the language themselves had the desire to take part in the project.

“Aboriginal people can own a language without even speaking it, so there is a distinction between ownership and user-ship,” Professor Zuckermann explains.

“It doesn’t matter how much I give and how much effort I put in, it will never be my own language and I will never be allowed to have this language as owned by me.”

In December 2016, Professor Zuckermann and the Barngarla Language Advisory Committee (BLAC) launched the Barngarla Dictionary app, as a means to ensure their work is accessible to generations to come. All recordings done for the app were voiced by Barngarla people.

READ MORE ABOUT THIS STORY

Could language revival cure diabetes?

But the journey has been bitter-sweet. By spending copious amounts of time in disadvantaged communities, Professor Zuckermann has also been heavily exposed to the same troubling issues that affect many remote Indigenous communities. However, the observation that language reclamation was providing a sense of pride gave him the idea to extend the scope of his research to establish the potential links between language reclamation and mental health.

“For me, if you put a gun to my head, the number one single most important component of identity, culture, sovereignty, intellectual sovereignty, spirituality, metaphorically speaking, your soul is language.”

“When you deal with heritage reclamation and reconnection, you cannot escape the feeling of loss, the feeling of vacuum, the feeling that there was something there and it’s not there, and then you try to regain it.” Professor Zukermann firmly believes that it is his moral and ethical duty as a migrant to engage in Indigenous language reclamation.

Professor Zukermann firmly believes that it is his moral and ethical duty as a migrant to engage in Indigenous language reclamation.

Prof Ghil'ad Zuckermann and Kaiden Richards while working on the app. Source: Supplied

“Aboriginal languages are worthy of reviving, out of a desire for historic social justice. They deserve to be reclaimed in order to right the wrongs of the past.

“The second reason for Aboriginal language revival is aesthetic: Diversity is beautiful, aesthetically pleasing. It’s fun to listen to a plethora of languages and to learn odd and unique words.”

A tale of two migrants

The irony of Professor Zuckermann’s story is that he, a descendant of a German holocaust survivor, used a dictionary written in 1844 by another migrant - the German Lutheran missionary Reverend Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann - to revive the Barngarla language.

“The fact that we use it today, 175 years [later] to reconnect [Aboriginal people] with what was lost by Anglo-Australians, and the fact that this meant there was a symmetry here of two migrants from Europe or from say Europe and the Middle East, is fascinating. I really think this is a UNESCO story.” For Professor Zuckermann, working closely with and for Aboriginal people has not just recalibrated his experience of Australia – it has also made him feel ‘more Australian’.

For Professor Zuckermann, working closely with and for Aboriginal people has not just recalibrated his experience of Australia – it has also made him feel ‘more Australian’.

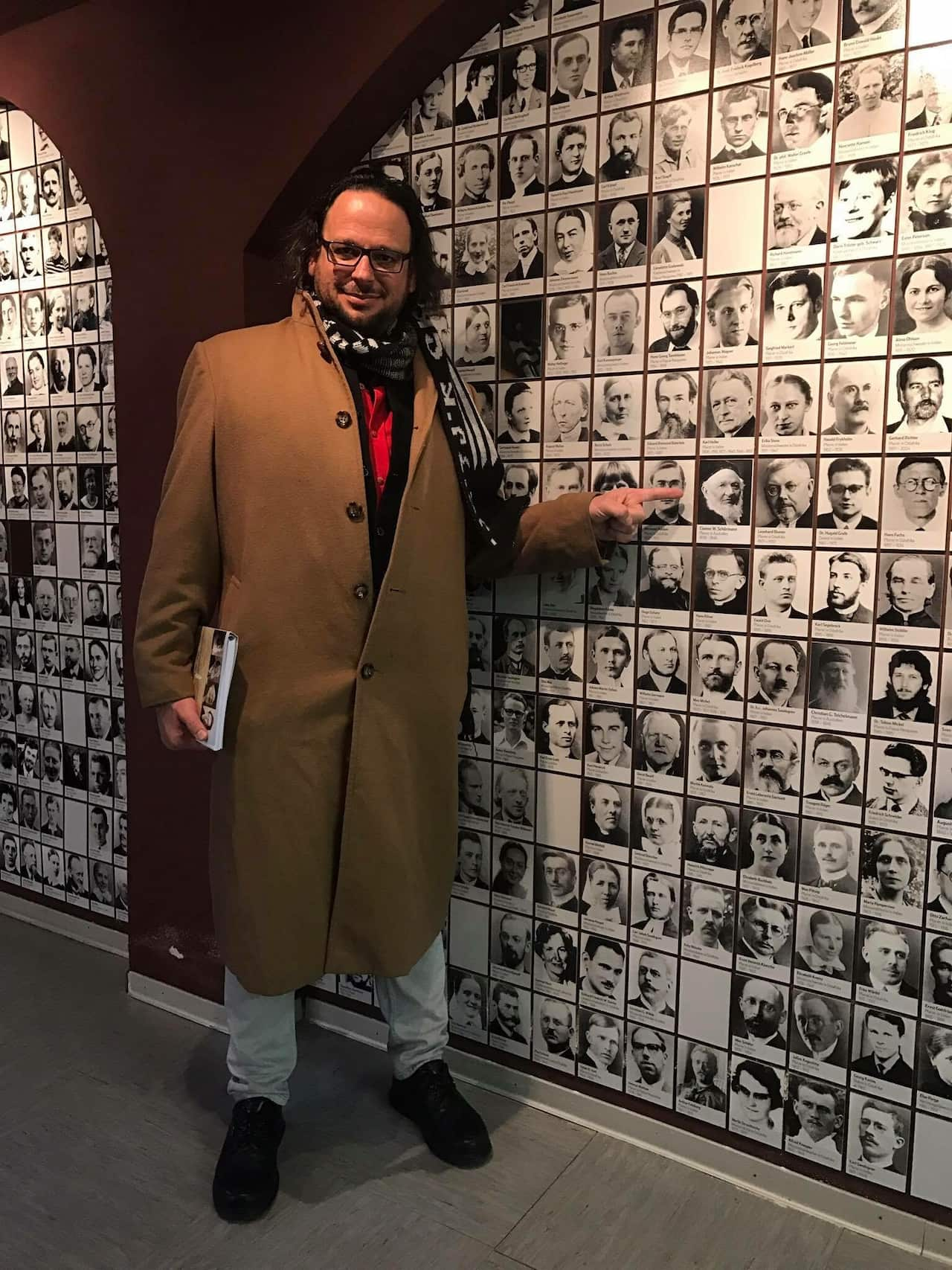

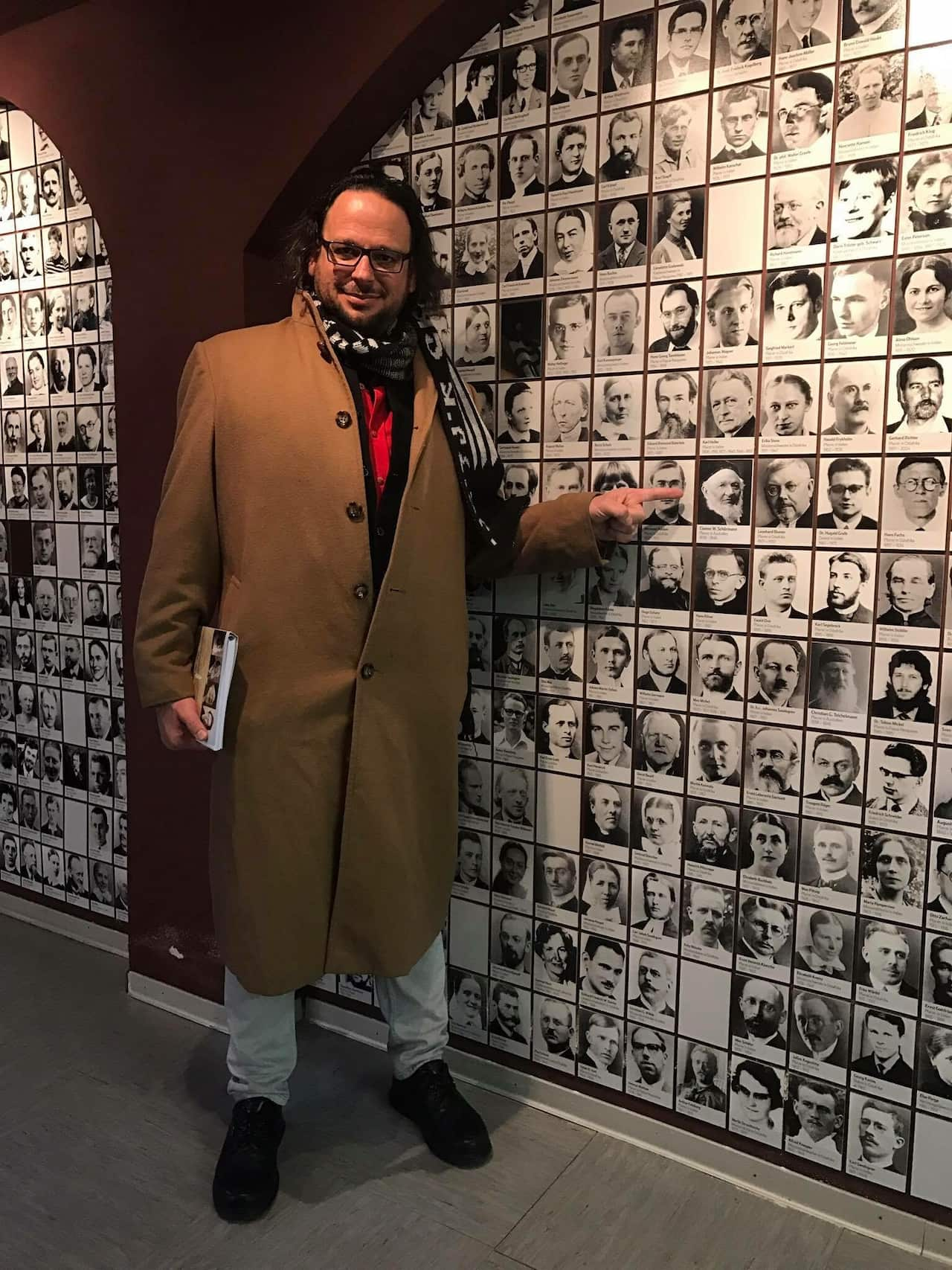

Professor Ghil'ad Zuckermann pointing at a photo of Revd Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann (1815 Germany – 1893 Australia), Leipzig Lutheran Mission, Germany. Source: Supplied

“It took me 12 years to become Australian, but I feel that I do something which rights the wrong of the past that Australia itself conducted. Therefore, it makes me feel even more Australian. It’s almost like I’m correcting the Anglo-Australian mistake,” he explains.

“Sometimes I feel that migrants from non-English speaking countries … and Aboriginal people in Australia, they have some kind of affinity because both of them historically have been discriminated against by Anglos. For example, Italians, Greeks, Vietnamese, etcetera, they have been discriminated against when they came 50 years ago. This is why we have a lot of language loss … even by migrants. Not too many migrants speak the language of their grandparents.”

Professor Zuckermann, Alfred Pek and I are saddened by the notion that so many migrants live largely unaware of Indigenous issues and culture. But after our experience with Aboriginal Australia, the three of us cannot help but feel wedged in the middle of a deeply-seated social dichotomy between mainstream Australia and the Indigenous peoples.

“It’s like having two parallel worlds in Australia,” Professor Zuckermann explains.

“You’re falling in-between the chairs, and this is exactly what I feel an Aboriginal person does too when he or she loses their language.

“[There’s] this feeling of [being] liminal, liminal as in the border of two societies. Obviously, I’m not an integral part of the Aboriginal society, but on the other hand, I’m not an integral part of the mainstream,” he adds.

Photographer Sunny Brar with Bonita Mabo. Source: Supplied/Sunny Brar

‘A visitor or a resident of someone else’s land’

For Indian-born photographer, Sunny Brar, years of self-initiated contact with Indigenous Australians has reshaped his life, career, and deepened his sense of belonging.

Sunny arrived in Australia when he was only seven years old. Growing up as a cultural hybrid, he grappled with his own concept of identity and heritage growing up.

“[I had] a need for myself to understand my own culture … to understand where I came from.”

While working for the South Sydney Rabbitohs during the Indigenous round, he had an epiphany: “I saw how everyone else was struggling also to identify with their own culture or figure out [their own] heritage,” he recalls.

Sunny decided to embark on a self-funded project to capture ‘the face of Australia’, community by community. His starting point was First Australians, to give respect where it is due. And the reward was beyond expectation.

Sunny spent eight months travelling from Sydney to Townsville, from Dubbo to Canberra and the Gold Coast, and many other places, to get to know some of the most recognisable and emblematic faces of Indigenous Australia.

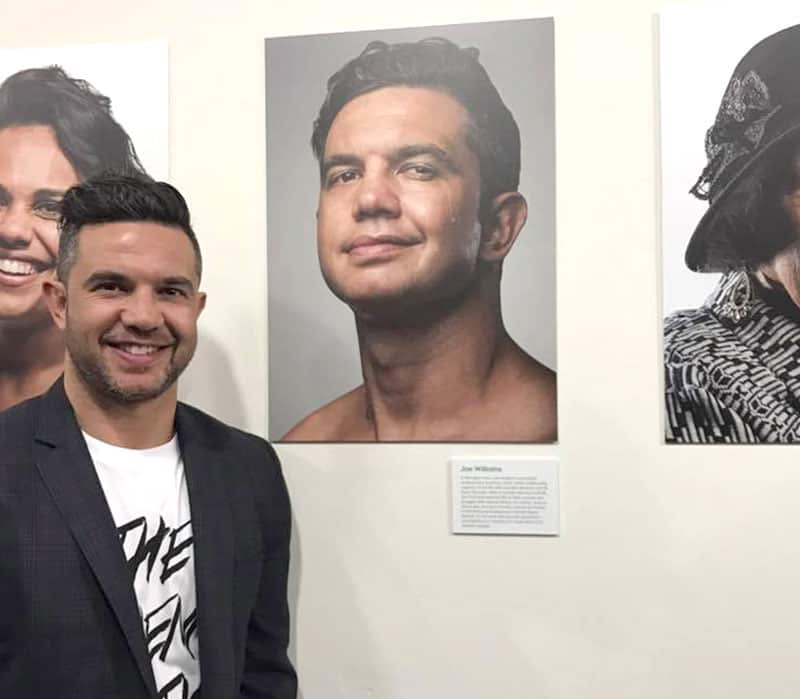

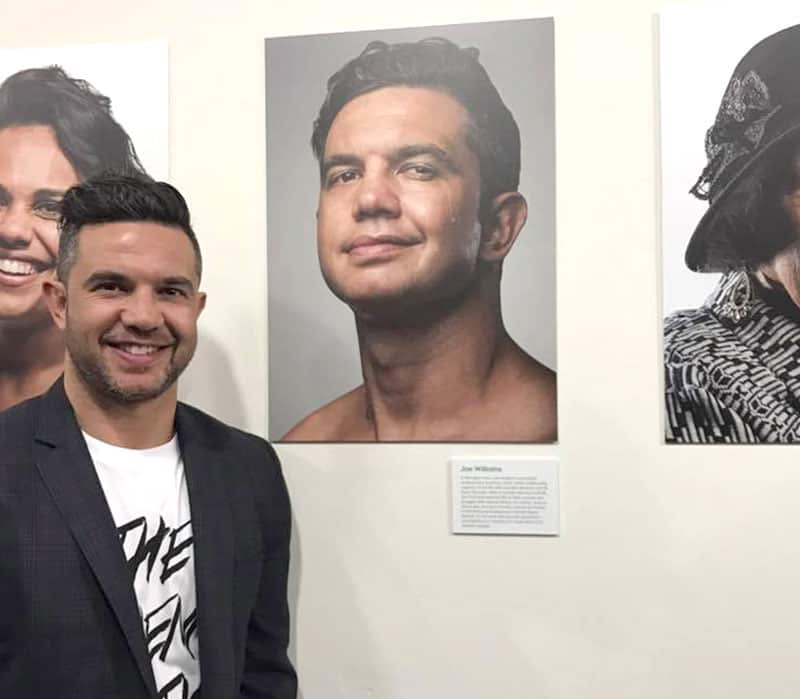

From sporting legends like Nova Peris, Joe Williams and Jade North, to activists like Bonita Mabo and Clinton Pryor; from actors like Jack Charles, Luke Carroll and Miranda Tapsell, to politician Linda Burney and Redfern Senior Constable, Jarin Baigent, Sunny captured used his craft to capture the charisma of a group of formidable Indigenous Australians. He displayed the work in an exhibition called ‘The Face’.

MORE ABOUT THE FACE EXHIBITION

Faces of Indigenous heroes celebrated in new photo exhibition

The experience provided a window into new worlds – both externally and internally.

“Through this time I actually got to know what it meant to be Indigenous Australian and what it meant for myself as an immigrant, but also what was expected for Australians to be when we come here to look after land,” Sunny says.

“The time that I spent with these people really showed me the values that they hold quite dear to them, which is the value of culture, the value of family, and also the value of land, which they respect so much in everything that they do. I did not know that before and made me really realise and kind of, it made me appreciate the land that I walked on and the proud history behind it.”

Sunny says this experience also changed the way he now approaches and talks to people, the way that he introduces himself and where he’s from, especially when meeting someone Indigenous.

“Whenever I do visit a new area, I try to always understand who were the people, the mob, and it kind of has educated me to look into further learn about different areas and different cultures and rituals of that area,” he says.

“It has [also] really changed the way that I engage with non-Indigenous people and whenever a question is raised about whether what I know about Australia or who I am, I always refer to myself as a visitor or a resident of someone else’s land.” Sunny now feels more at home and even more connected to this land – which is quite the statement, given how elusive and contentious the concept of ‘home’ could be for many of us migrants.

Sunny now feels more at home and even more connected to this land – which is quite the statement, given how elusive and contentious the concept of ‘home’ could be for many of us migrants.

Source: Supplied/Sunny Brar

“It has made me feel more at home, I wouldn’t quite really say ‘more Australian’ because it’s made me realize more about myself and more about the people around me.

“[It has] definitely made me feel more comfortable walking around and interacting with different people, but I guess that’s part of being Australian, it’s that inclusive, working together kind of mentality, and working together for the greater good of other people, so in that sense, it has made me more self-aware.”

This is a sentiment shared by both Alfred Pek and Ghil’ad Zukermann.

“If there had been no Clinton’s Walk for Justice, I wouldn’t have [had] the interactions that I’ve had with a lot of the different Indigenous communities; I would not have the new profound respect that I’ve got towards a lot of these people; I would not have the incentive to meet a lot of these First Nations communities, because there was no platform, there was no vehicle for that,” Alfred says.

“[It’s] something that I would’ve never thought in my life until that happened.”

Just like me, Alfred questions why Australia still doesn't offer widespread cultural programs to support greater understanding between Indigenous people and migrants. Although immersive Indigenous-led tourism experiences are becoming increasingly more popular, there are few guided or supported opportunities for newbie migrants to interact with Indigenous Australians long-term, unless they seek out the experience independently. The push seems to be for migrants to integrate to the mainstream, and not to engage with First Australians.

“A lot of migrants or a lot of visitors, they want to learn, they want to get out of their way to actually understand ‘what is this land?’, ‘why is Australia so fascinating?’, ‘what makes this story?’,” Alfred says.

“If it wasn’t for the fact that we (as migrants) have to venture out of our comfort zone, and come to this land to find better opportunities, we would have less incentive to be exposed to a lot of this new information,” he adds.

Professor Ghi’lad Zuckermann feels Aboriginal people are “an integral part of Australia”, and cannot conceive his experience of this land without them.

“My whole existence in Australia is based on my collaboration with Aboriginal people from various groups, especially the Barngarla people of the Eyre Peninsula.”

“I do know migrants and Aussies for whom ‘Australia’ is not ‘Aboriginal’, so ‘Australia’ [as a concept] can exist without Aboriginal people. For me, Australia without Aboriginal people is a non-sequitur,” a Latin term that describes ‘an invalid proposition’ in formal logic.

As for me, I now too cannot fathom Australia without its First Peoples. After two years in the desert and almost two years working for Australia’s National Indigenous Television, I now feel embarrassed at my own naivety to have not initially understood how my colleagues have always been just as Indigenous as the Traditional Owners that welcomed me to the desert.

Just like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, I had to go to a foreign land to understand that what I was looking for was always home.