KEY POINTS

- Australians will vote on an Indigenous Voice to Parliament on 14 October.

- Proponents say the Voice will give Indigenous people a say on policies impacting them.

- But opponents argue the Voice either goes too far or not far enough.

Australians will decide whether to enshrine an Indigenous Voice to Parliament in the constitution when they head to the polls on .

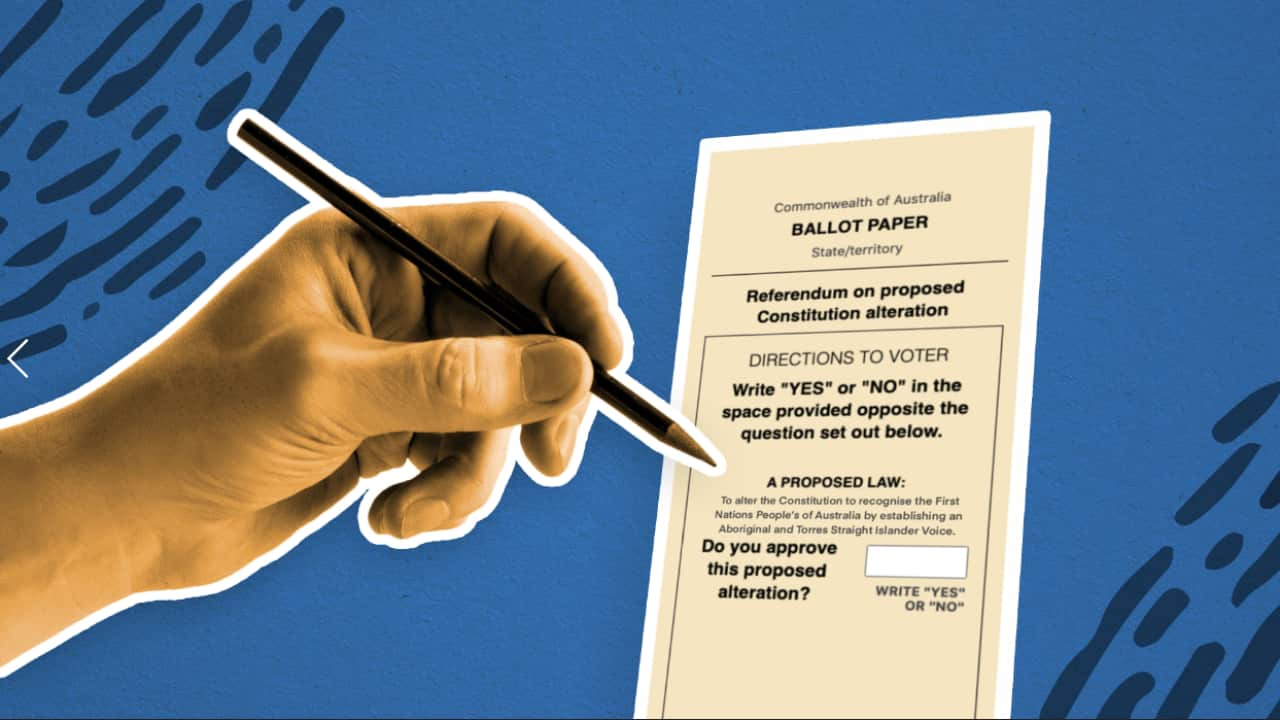

In the country's first referendum since 1999, they'll be asked to vote Yes or No on this question:

A proposed law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?

Unveiling in March, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese described the Uluru Statement from the Heart - which - as a "gracious request" that would give Indigenous people input in policies that were particularly impacting them.

"Every Australian wants us to close the gap. Today points the way to how we are going to do it. By consulting the people on the ground, by working with the people who live alongside these challenges. By enshrining a Voice in our Constitution, and by listening to that Voice," he said.

Arguments for and against enshrining the Voice

Campaigners for Yes say the case is simple: it's about listening to Indigenous Australians when policy about them is made, and recognising them in the constitution.

But No campaigners have cast doubt over how the Voice would function. Some opponents argue it would go too far, while others say it wouldn't go far enough.

Here are the key arguments, as put forward by each camp:

YES

- The Voice was recommended after a years-long engagement with Indigenous communities across Australia.

- Indigenous people should have a say in policies that affect them.

- If the government listens to Indigenous people as it creates policies about them, the policies will be better.

- When governments listen to people, they use funding more effectively. So the Voice would save money.

- The Voice would advise government on practical steps to improve Indigenous health, education, employment and housing.

- Future governments wouldn't be able to remove the Voice without another referendum, meaning it could offer unwelcome advice without fear of being shut down.

- The Voice would be gender-equal and include youth members, meaning more voices from Indigenous communities will be heard.

- Parliament, and by extension the Australian people, would still hold the ultimate say over what becomes law.

- It has been carefully devised and given the green light by legal experts.

- Fixed terms mean representatives will always be accountable.

- The Voice would be a good mechanism through which to negotiate Truth and Treaty processes with the Commonwealth.

NO

- It's symbolic, and fixing systemic issues facing Indigenous communities would require a body with actual power.

- More bureaucracy will not help Indigenous Australians in disadvantaged communities to close the gap and achieve reconciliation.

- Governments can ignore its advice if they don't like what it tells them.

- No issue is beyond its scope.

- The Voice adds race to the constitution, and enshrining a body for only one group means permanently dividing Australians.

- Australians are being asked to sign a blank cheque, given key details about how the Voice would operate will be decided after the referendum.

- Because the Voice will be designed by parliament, future governments could change or sideline it.

- It will be a first step to more radical changes like financial reparations for colonisation and dispossession.

- It would be costly and bureaucratic - an additional fiscal burden on top of existing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representative bodies.

- Indigenous people already have a voice via an unprecedented level of Indigenous representation in parliament.

- Truth and Treaty should come before the Voice.

Who is behind the Yes and No campaigns?

The most prominent campaign backing the Voice is Yes23, led by the group Australians for Indigenous Constitutional Recognition (AICR). Trade unions and the Business Council of Australia are also making a rare show of unity in supporting the Yes case.

In parliament, the push for a Voice is - including Albanese and Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney - the Greens, and most independent MPs. A small number of Liberal MPs, such as Bridget Archer and Julian Leeser,

Notable Indigenous figures in the Yes campaign include Professor Megan Davis, Noel Pearson, Thomas Mayo, Tom Calma, Marcia Langton and Pat Anderson. They’re all long-term, prominent advocates for Indigenous social and economic justice who’ve been involved in shaping the Voice proposal.

Davis, Anderson and Pearson were all co-chairs of the Referendum Council, a body set up in 2015 that consulted with hundreds of Indigenous people and eventually produced the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Calma and Langton were co-chairs of the

One of the most influential groups in the No camp is ADVANCE (formerly Advance Australia), which set up the subsidiary organisation Fair Australia for the Voice campaign. ADVANCE was founded in 2018 as a conservative equivalent to progressive advocacy group GetUp.

The organisation - which is backed by several wealthy corporate donors - describes itself as "fighting hard" to keep the hands of "woke politicians and the inner city elites" off people's "freedom to be Australian".

ADVANCE has many personal and political connections to the Liberal Party - unsurprising, given that the Liberal Party is also spearheading the No campaign, alongside its Coalition partners, the National Party.

Some of the most prominent figures in the No campaign include Opposition leader Peter Dutton, Nationals senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, and Indigenous businessman, political strategist and Indigenous advocate Warren Mundine. Nationals MPs such as David Littleproud and Barnaby Joyce have also been outspoken in their objection to the Voice.

Broadly speaking, the aforementioned figures say they oppose the Voice because it goes too far. The other side of the No camp, , argue that it doesn't go far enough. Independent senator Lidia Thorpe and activist and lawyer Michael Mansell are prominent figures on this side of the No campaign.

Stay informed on the 2023 Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum from across the SBS Network, including First Nations perspectives through NITV.

to access articles, videos and podcasts in over 60 languages, or stream the latest news and analysis, docos and entertainment for free, at the