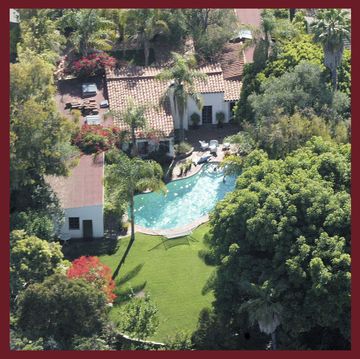

When Paul Szápáry invited a girlfriend to his summer home in Newport as a young man, he told her he lived in a big house to prepare her for the fact that the "big house" was the Breakers, the 70-room Gilded Age mansion his great-grandfather Cornelius Vanderbilt II built in 1893.

But Szápáry, 67, won't be living there much longer. "The residential occupancy of the Vanderbilt family apartment on the third floor by Paul and Gladys Szápáry, the children of Countess Anthony Szápáry, has ... been voluntarily discontinued," read an announcement issued last week by the Preservation Society of Newport County, which owns and operates 11 historic properties, the most popular of which is the Breakers.

The Szápárys have spent summers in the Newport "cottage" since birth, like generations before them. Their grandmother, Countess Gladys Széchenyi, invited tourists into her summer home to raise money for the fledgling Preservation Society and leased it to the organization for $1 a year in 1947. The Society bought the Breakers from her heirs for $366,475 in 1972. Széchenyi's daughter, Countess Anthony Szápáry, continued to live on the upper floor, as did her children following her death in 1998. The space includes eight bedrooms and a living room overlooking the ocean, and like the other bedroom suites on the second floor, it was decorated by famed architect and designer Ogden Codman, Jr.

While they did not have a formal lease, an arrangement with the Society that allowed them to keep living on the upper floor was once deemed mutually beneficial by a Preservation Society official. "It will be helpful to us to be able to tell our visitors that the original owners' great-grandchildren continue to live in the house," the non-profit’s then-board president reportedly wrote in a letter to Paul and his younger sister, Gladys, in 1998.

But now the tune has changed.

"A year-long study by a preservation architect and an engineer concluded that the ventilation, electrical, and plumbing systems, while completely safe for museum use, were dangerously outdated for residential use, putting the structure and collections at risk," this week's announcement said. "In view thereof, elements of the historic building’s 120-year-old plumbing and electrical systems are being decommissioned on the upper floors."

While the statement is identified as a "joint announcement" from the society and the family, suggesting an amicable parting, Paul and Gladys's cousin Jamie Wade Comstock, whose great-grandfather Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt died on the Lusitania, says there's more to the story.

She believes the Preservation Society's reason for her cousins' departure is what she calls a "pretense."

"The Szápáry family worked hard for many years to keep the third floor as safe and up to code as possible," she wrote on Facebook. "They often made repairs at their own considerable expense—and were always open to outside repair professionals coming in for the PSNC."

She said that the Szápárys "did not agree to move out" and "were given a deadline and a legal ultimatum" (neither of her cousins has children, so it seems likely that the arrangement would have ended upon their deaths). To get in to remove their personal effects, they apparently now have to make an appointment and be escorted by Preservation Society employees.

"You have [a matter of] months to remove 120 years worth of your family's material out of 20+ rooms," she wrote on Facebook. "Now GET OUT while we tell everyone how we are rescuing you from an unsafe space (which we are charging thousands of people money to visit while you pack). Completely absurd."

Harlem-based historic preservationist Michael Henry Adams believes that the change is retaliation for the Szápárys' opposition of the Breakers Welcome Center, the plan for which other members of their family, including Gloria Vanderbilt, also opposed. (Vanderbilt and her son, CNN anchor Anderson Cooper, declined to comment for this story.)

The planned welcome center will be located inside the main gate of the Breakers, on the site of a current ticketing tent (then-board chairman Donald O. Ross discusses it in the 2013 video below). "Occupying a modest 3,650 square feet, the welcome center will offer visitors information about The Breakers, other properties of the Preservation Society and the city of Newport itself, along with refreshments and comfortable restrooms," reads a description of the facility on thebreakerswelcomecenter.org. Work has been taken "to ensure no irreversible alteration to the landscape occurs, no historic fabric is lost and the historic viewsheds – both inside and outside the grounds – are preserved."

But Adams and others say it doesn't belong on the grounds of the National Historic Landmark. Last July, a group including Adams and former Preservation Society trustee Ron Fleming stood outside the Breakers to protest the center. (They suggested building it across the street on land already owned by the Preservation Society, an option that the non-profit says it considered and ultimately rejected.) A year ago, the Rhode Island Supreme Court Supreme Court let stand a lower court ruling denying a challenge to the center that would prevent its construction, and last May the Preservation Society broke ground on the building, which will include indoor ticketing and food services.

"It's utterly transparent when they use this specious excuse about the ventilation and plumbing and electrical wiring being unsafe for human habitation," Adams says.

When asked for comment, a representative for the Preservation Society, wrote, "The statement that I sent to you is a Joint Statement by the Szaparys and the Preservation Society. We have no further comment."

The first sentence of the statement seems to acknowledge the Society wants access to the previously private space occupied by the brother and sister. It says, in part, that the change will "make way for possible future public access to upper portions of the building that have not previously been accessible by the public, including the former servants' quarters."

Fleming believes there is another incentive for the Society to build the center: "What they really wanted to do is monetize the property as much as they could through corporate rentals, with the backdrop of the house providing a whole other income stream."

Trudy Coxe, executive director and CEO of the Preservation Society, has previously said, "We have always believed in the unique merits of the Breakers Welcome Center." At the groundbreaking, she told local news station WPRI, "I don’t know of a museum in America that doesn’t have a place to eat. It’s standard policy now. It’s just the way things are done."

Adams believes that Countess Széchenyi's decision to lease her home to the Preservation Society was made in the hope that the property could remain a family home while also being open to the public. "She was inspired by the idea of noblesse oblige—she wanted to benefit all of Newport and get people to see the architectural glories of the century—and by making the choice I feel she really did, without realizing it, lead to this situation where her family members are being tossed out. It's appalling."

Adams and fellow preservationist Fleming (seen at the July protest in the YouTube video below) pointed out that similar historic houses in the United Kingdom managed by the National Trust often highlight the residents who still live in them. There's perhaps no better example of a historic house open to visitors than Highclere Castle, the setting of Downton Abbey, and still the home of the eighth Earl and Lady Carnarvon.

"This is our Downton Abbey," Adams says.

Other community members are similarly up in arms, and have been for years; a 2013 New York Times article on the visitor center proposal notes that "letters to editors are pouring in on both sides of the debate."

In a letter to the editor of the Newport Daily News, local bookstore owner Robert B. Angell wrote, "The society can spend $3 million on a welcoming center [Editor's note: the Preservation Society estimates the cost will be $4.2 million], but cannot spend money on repairs to bring the apartment up to code. If closing the apartment is not blatant payback for opposing the welcome center, I do not know what is. When is someone going to stand up to these bullies?"

The family seems to feel keenly the loss of their home—and the changes in store for the property. Comstock says she simply can't express "how sad and dispiriting it has been for our family. We had looked forward to continued good relations with the Preservation Society, but we just felt so ignored and marginalized during every part of the visitor center planning process."

"Visitors will soon find that the gilded cage was much more interesting when it still had the birds inside it," she said.

Sam Dangremond is a Contributing Digital Editor at Town & Country, where he covers men's style, cocktails, travel, and the social scene.