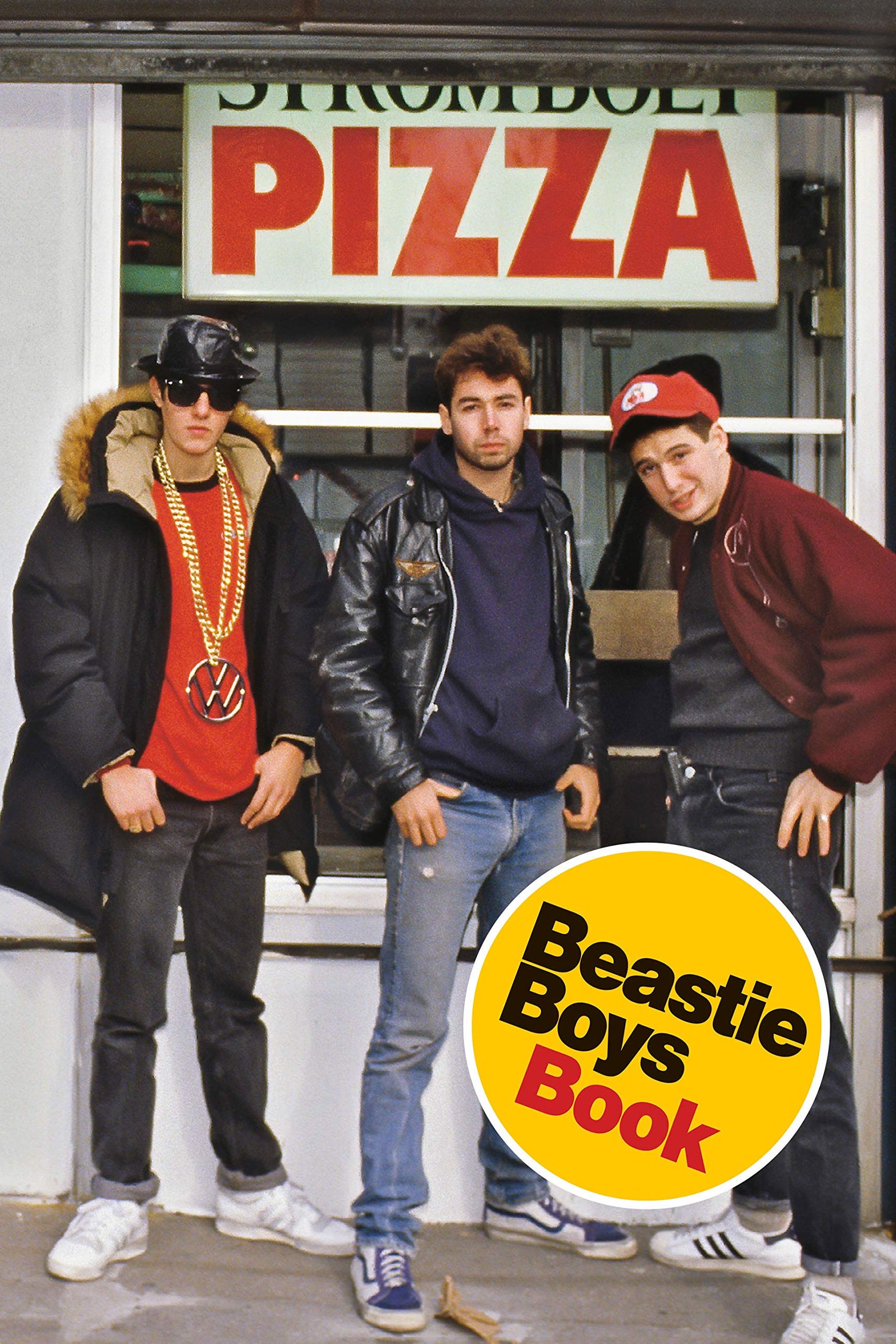

The Beastie Boys Book, the cinder-block-shaped testament to three decades of hip-hop shenanigans by Mike D and Ad-Rock, is a conversational and personable trip to a brighter, more fun world. It’s full of stories about MCA’s family dog stealing a pizza and Mike D getting freaked out by Bob Dylan at a party. But a bigger, more hopeful story undergirds the entire book: the Beasties’ journey from the toxic misogyny of their early days to the relative enlightenment of their late career.

The misogyny of the Beastie Boys’ early years was noxious and pervasive. The song “Girls” is both appallingly sexist and entirely typical of the group’s first album. Live shows of that era featured women in cages dancing onstage and a giant hydraulic penis. The misogyny extended past the band’s creative output: As the group transitioned from punk to hip-hop, drummer Kate Schellenbach was gracelessly dropped from the lineup for not fitting with the emerging bro-centric direction.

And then a miracle happened: The Beastie Boys heard criticisms about being misogynistic, homophobic jerks and actually listened to them. And changed their behavior. Sexist lyrics stopped appearing in their songs, and the 1994 song “Sure Shot” famously included a verse in which MCA explicitly apologized for the group’s past misogyny. Ad-Rock wrote a letter to Time Out New York apologizing for the band’s past. In 1998, the Beasties publicly beefed with the then-hot band Prodigy, asking them not to play the song “Smack My Bitch Up” at a festival where both acts were appearing.

Amid many apologies and statements of regret about their youthful behavior, Beastie Boys Book includes a chapter written by Kate Schellenbach, giving her side of the story on her ouster from the band. Schellenbach reconciled with the Beasties, who then championed her subsequent band Luscious Jackson on their Grand Royal label. As Jack Hamilton observed in his Slate review of Beastie Boys Book, “Somehow the guys who’d risen to fame playing shows in front of an enormous hydraulic penis turned themselves into a model of how to grow up gracefully.” Disarming the tired argument about sensitivity negating comedy, post-reformation Beastie Boys material is still tremendously fun.

Reading this, I was struck by a contrast. Life in 2019 as a conscious person seems to mean reserving a few minutes every day for an inevitable shot of white-hot disgust at the misguided comeback attempt being mounted by Louis C.K. Of particular offense is his apparent pivot towards reactionary outrage comedy, revealed in the bootleg of a show at a Long Island comedy club that emerged in December.

Despite a pledge to “step back and take a long time to listen,” C.K.’s new material paints himself as the victim. “What’re you gonna do, take away my birthday? My life is over, I don’t give a shit,” he says in a set that also laments how much money he has lost. In a January set from California, he makes ain’t-I-a-stinker? jokes about masturbating in front of women.

As a culture, we keep seeing famous, talented men behave abhorrently towards women. It’s all too rare for them to get called out or suffer consequences for it, but the responses are instructive. The Beastie Boys responded to criticism by examining themselves and changing their behavior; C.K. appears to be responding to criticism by raising both middle fingers, embracing his worst instincts, and taking other members of the Gen-X comedy firmament with him.

Louis C.K. has much more to atone for than the Beastie Boys, and it’s an open question whether such atonement would even be possible. One essential step would be to use his still-high profile in the comedy world to further the careers of the women he victimized, as the Beasties did. But the question of how exactly C.K. could atone appears to be academic, given his apparent utter disinterest in even trying. His retreat into victimhood and reactionary comedy makes for a sharp, sad contrast with the Beastie Boys, and makes the latter’s reformation seem all the more miraculous.

It’s easy to imagine a world where the Beastie Boys took the C.K. route. The career and existence of Kid Rock proves that the market for sleazy, sexist white rap existed during the period during which the Beasties reformed. They could have made a fortune (per Wikipedia, Kid Rock sold more albums than they did in the ’90s) and could have been embraced by the right as bold truth-tellers who refused to bow down to the PC thugs. The darkest alternate timeline sees the still-raunchy Beastie Boys trundle out the hydraulic penis for a set of Licensed to Ill material at the Trump inauguration. Of course, they would have had to live with themselves. On top of all the other pleasures it offers, Beastie Boys Book reminds us that there are some artists who can’t live with the bad behavior they once exhibited—and who therefore do the hard work of making amends.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.