In early 2019, just a few months before Abigail Disney, Walt’s grand-niece, took to Twitter to denounce the company’s pay practices, news surfaced about a 76-year-old man, a former Disney star, who was missing from the tiny town of Phoenix, Oregon. Dennis Day, one of Disney’s original Mouseketeers, had not been seen for six months. Together, the stories might have dominated headlines, illuminating the ways in which Disney profited from the labor of its most vulnerable workers. But the two news items were drowned out by the company’s forecast-busting revenues, its acquisition of Fox, the announcement of Bob Iger’s impending—and, as it turned out, temporary—departure from his long-standing role as CEO, and Disney’s release of 10 of 2019’s highest-grossing movies. That year, the American public seemed to have an appetite only for good news from “the House of Mouse,” logging more visits to its amusement parks than ever before and tucking into the hero-rich world of Marvel. Consumers weren’t particularly interested in tying the happiest place on Earth to issues of social welfare that, by 2020, would, in fact, attract their attention. In 2019, it didn’t take long for the furor over Abigail Disney’s criticism to fade. But tragic stories about fallen child stars always garner clicks, so national news outlets and international tabloids eventually picked up the Day story.

The media coverage of his disappearance generated more questions than it did leads. The public struggled to place Day’s southern Oregon home on the map and his aged face and unkempt appearance alongside images of more famous Mouseketeers like Annette Funicello and Cubby O’Brien. Many wondered how a onetime beloved young Hollywood star could be missing for so long. Early news reports offered little information. On July 13, 2018, Day had made several calls to 911 seeking assistance for his husband, Ernie Caswell, who suffered from dementia and had fallen several times. For the next two days, Day was a constant presence by Caswell’s side at the local hospital. But after July 14, Day abruptly stopped visiting or even checking in by phone. The hospital staff were alarmed enough by the sudden change to call the Phoenix police and ask for a welfare check.

Discuss Dennis Day's life and death on Alta Live on Wednesday, January 17 at 12:30 p.m. Pacific time.

REGISTER

Phoenix, Oregon, occupies less than two square miles of dry mountain land. The closest major cities are Portland, more than 250 miles to the north, and Sacramento, 300 miles to the south. It has a population of less than 5,000 and an operating budget that hovers around $5 million. Its police department receives a little more than 6 percent of that budget, but the funding doesn’t go far in a place witnessing a rapid rise in the use of fentanyl and other illicit drugs as well as a countywide rise in crime and an influx of cartel-run trafficking operations. A full day passed before an officer traveled the three blocks from the station to check on Day at his 1,800-square-foot, single-story house. The property was in disrepair, and junk and garbage littered the gravel driveway and the porch. The officer surmised that Day had fallen on hard times.

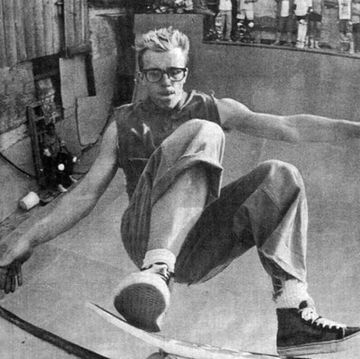

Six months later, looking at the images of Day and his home on the news, the public would be led to draw the same conclusion. The frail-looking Day in the media reports bore little resemblance to the wide-grinned, radiant boy wearing Mickey Mouse ears pictured in Disney promotional photos. On the missing person poster, both Days peered out under a banner reading “Have You Seen This Mouseketeer?”

For most people, the answer was no. That’s because it had been decades since Day’s stint as a charter member of Disney’s breakout, era-defining 1950s TV program The Mickey Mouse Club. That show, and its three subsequent revivals, spawned pop culture icons who span seven decades, ensuring that every living generation of Americans has grown up following the careers and personal lives of Mouseketeers. Their stories, from the highs of music and movie stardom to the lows of illness and addiction, have played out in the public eye, sometimes, as with Britney Spears, with disastrous results. Often, the lives of these young stars highlight the fleeting nature of fame, the quiet desperation some people endure despite the personas they project, the complicated nature of fandom, and our collective fascination with the downfalls of others, regardless of the consequences.

By Day’s own admission, it had been a slow descent from a false high.

As a young kid, Day moved with his family from Las Vegas to Los Angeles, where he studied dance and theater. He had something special, and by the time he was 11, Hollywood had noticed, casting him in small television roles, commercials, and educational films and then in the 1953 movie A Lion Is in the Streets, with James Cagney. A little more than a year later, Day and 3,000 other kids auditioned for a new Disney variety show. Only 24, including Day, received an offer. Did Dennis, Disney asked, want to be in the Mickey Mouse Club? Did he want to be a Mouseketeer?

Of course he did.

The show debuted on October 3, 1955, and was an instant ratings hit. Its hallmark was the roll call, in which the Mouseketeers shouted out their names during a lively song-and-dance routine. Only the most popular of the Mouseketeers, those on the production’s Red Team, were included. Day, who had slipped into the cast despite not being able to sing, was on the lower-ranking Blue Team, whom fellow cast member John Lee Johann later called the “extras.” When Day eventually made it to the Red Team, he discovered that not being able to sing mattered—he got skipped over for many roles and didn’t attract hordes of devoted fans. To stay on the show, the young actors had to be a lot of people’s favorite Mouseketeers. “We were the envy of every child in America and their parents too,” said fellow Mouseketeer Tommy Cole in a later interview, but “we knew we were replaceable.”

After two years, Day was released from his contract. By then, the show had garnered an estimated 25 million young viewers, and Disney had sold more than two million pairs of mouse ears. The Mouseketeers were a gold mine, and everyone knew it, especially Walt Disney, who told cast member Doreen Tracey, “Do you realize that this is the greatest thing you will ever do in your whole life?”

According to Day’s friend Rosanne Reynolds, Walt’s statement proved true for the aspiring performer during the first decade or so “after the Mouse.” The money from licensing didn’t trickle down to the cast, and the fame, while propelling some Mouseketeers to major Hollywood success, didn’t open any doors for Day. He struggled to break into the big time as an adult, working in regional theater and as a choreographer. But he did find work. According to Reynolds, he choreographed the first stage adaptation of Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree and at least one piece by the New York City experimental theater group La MaMa, which incubated greats like Bette Midler. To pay the bills, he taught acting and dance classes. He didn’t talk about Disney very much, if at all. In the late 1960s, he became part of the counterculture’s burgeoning Great Dickens Christmas Fair and Renaissance Pleasure Faire scene. The vision for those events, according to Kevin Patterson, the son of the fairs’ creators, was to build an alternative, arts and crafts–based economy through the production of immersive, multidisciplinary, participatory arts experiences. Day’s fleet-footed, fearless, and physical performances made an impression on the tens of thousands of attendees—and made him a luminary. “Dennis commanded attention and took the stage in a way that wasn’t egotistical but honest and completely real,” says Patterson.

Soon, Day became one of the Renaissance Faire’s directors and, as Patterson recalls, was a groundbreaking cultural influencer. Patterson credits Day’s ideas and work for much of today’s festival and communal culture at events like the Oregon Country Fair, Burning Man, and Coachella.

This article appears in Issue 26 of Alta Journal.

SUBSCRIBE

It was at the Dickens Fair in Marin County that Day met and fell in love with Caswell. And it was during Day’s early involvement in the group that he developed his own sense of training and production, which, like most things about the Renaissance Faire, stood in stark relief to the grinding hours and mainstream, image-conscious world of the Mickey Mouse Club. “Faire existed in direct contrast to the unreality of Disney,” says Patterson. “Media in those days even called the Faire ‘Dirty Disney.’ ” Day embraced the change; he was interested in authenticity. He called for bodies of all shapes and people of all kinds in his productions and demanded total commitment to one’s character; “Don’t justify it, do it” was a common teaching refrain. And he was known for daring reimaginings of theatrical classics. Day’s friend Sylvia McRae praises his half-hour, seven-cast-member version of Gilbert and Sullivan’s opera H.M.S. Pinafore: “You don’t get that from just being a tapping kid on TV.”

Beyond his performances, Day practiced a quiet and persistent form of equal rights activism. “Dennis also created a sense of safety in sexual orientation at a time that was really challenging,” says Patterson. “His response to oppression was to be radically expressive and free.”

The state of disarray and apparent poverty that greeted officers conducting a welfare check in July 2018 was a consequence of the very problem that Day and Caswell had tried to address—artists’ struggle to earn a sustainable, living wage that would provide stability into old age—five decades earlier when they moved to the Bay Area and ran a guesthouse for low-income artists and actors. But by this time, the couple had largely withdrawn into their Phoenix home, becoming what some described as reclusive. McRae recalls trying to visit Day around 2009: Day at first suggested they meet at a coffee shop and then canceled altogether. In hindsight, she says, it raised a red flag: “I don’t know if maybe there was something that he didn’t want me to see.”

To the Phoenix police department, with its seven officers and single lieutenant, Day and Caswell’s residence may have been just another dilapidated house—overflowing with the clutter of two longtime pack rats and collectors—in an economically depressed area. Over several days that July, the police spoke with concerned neighbors and an unconcerned man named Daniel Burda, who claimed to be Day and Caswell’s housemate and handyman. Burda assured the police that Day was fine, saying that he had mentioned going to visit friends. With no reason to doubt him, they suggested he vacate the premises until the owners returned and left it at that. Later, Lieutenant Jeff Price, who led the investigation, would say he’d thought Day might be voluntarily missing: “Sometimes people just up and leave, which is not illegal.”

Over the next two weeks, the police expanded their search, interviewing local friends who insisted that Day had no reason to travel and that even if he’d had one, he couldn’t have afforded to. Then, on July 27, the police received troubling information, this time from the local Meals on Wheels staff. Day hadn’t been picking up his meals. Officers searched the interior of the house, including the attic crawl space. They found nothing to indicate Day’s whereabouts and no signs of violence. But there was one thing: it now seemed that Day’s car was also missing. Something wasn’t right. Finally, Price and his team opened a formal missing person case. At that time, the police would tell reporters later, they still believed that Day would turn up. Maybe, they thought, he had felt overwhelmed by his husband’s health issues and needed to get away for a bit.

Unable to learn much from Day’s friends and neighbors, the police reached out to the Renaissance Faire community via Facebook. His former colleagues and old friends felt sure that something had happened to him. “I was concerned for his safety early on,” says Patterson, who refused to accept that Day might have just walked away, abandoning Caswell. “That was impossible to me, that he would do that.” So Day’s friends in the fair scene put together a missing person poster and distributed it across social and mainstream media. Day was a Mouseketeer, they reasoned. Surely that would garner some attention. They even sent their poster to Disney in the hope that the company would pick up or promote the search.

But Day had a complicated relationship with Disney and had been estranged from the company for some time.

In 1968, Disney called again. Would Day, the rep asked, like to do a reunion show for Mickey’s 40th birthday? Of course he would. Well, sort of. Over the years, the Mickey Mouse Club’s fandom had grown, and so had the public’s preoccupation with the members’ personal lives. Who knew what kind of attention reentering that world might bring? Not to mention the experience itself. In an interview with journalist Amie Hill for Rolling Stone three years later, Day recalled the reunion as a high-pressure, unpleasant experience similar to his time in the club. And he went on, describing his years at Disney as fraught with anxiety: he recounted his struggle to pass through puberty in the public’s eye and how he had felt coerced to conform to Disney’s fast-paced production standards and morality norms. He had coped during the reunion, he said, by being stoned for the show. In the pictures for Rolling Stone, Day has the horseshoe mustache and long shaggy hair of a ’60s bohemian; he appears confident, fit, comfortable in his skin, and shirtless.

It was a big deal. Leaving aside the shock of witnessing a half-naked Mouseketeer swearing, admitting to using drugs, and enthusiastically coming out as gay, it was the first time a Mouseketeer had publicly criticized Disney. In 2015, Hill said in a public Facebook post that the company had been so unhappy with the interview that it banned any use of material from it in Disney-sanctioned books about the Mickey Mouse Club.

Even so, Disney called Day yet again, in 1980, for a second reunion. At the time, Day and Caswell were still living in Northern California. They worked the Renaissance Faire together while Day continued to teach and Caswell, who had a graduate degree from UC Berkeley’s School of Applied Theology, served as a presiding bishop in the Archdiocese of San Francisco. Still, the lure of the Mouse was strong for Day, and he agreed to participate and attended the weeklong rehearsal at the company’s Burbank studios. In the broadcast, it’s clear his romance with the club was over. In the finale, Day, tidied and trimmed but still sporting a mustache, can be seen at the far end of the back row, standing slightly apart from his fellow performers as they sing their trademark goodbye—“M-I-C (See you real soon!) K-E-Y (Why? Because we like you!) M-O-U-S-Eeee!”

Shortly after the second reunion, Day and Caswell moved to tiny, conservative Phoenix, where they made their livings selling jams and jellies at regional fairs and working for the fruit basket company Harry & David. The pair settled in happily there as self-described “militant gays.” They lived in a cheerfully bright lavender house; Day did choreography for a gay men’s chorus in nearby Ashland in which Caswell sang. They took their Sunday dinners at the local diner dressed in flamboyant suits and feather boas that put them far outside Phoenix’s social norms. As Day’s friend Doug Olsen puts it, “that was Dennis: challenging, liberating, and compelling. And also more than a little nuts.” The locals’ opinions of the men, whatever they might have been, were cemented in 2009 when, in response to a statewide battle over same-sex marriage, Day and Caswell, along with several other couples, wed in a public ceremony. The controversy made national news.

In the summer of 2018, Day’s disappearance was still months from making national headlines. The police continued to question anyone in Phoenix connected to Day. One local friend, Kirk Pederson, told them that in the months before Day’s disappearance, he had recommended that Day and Caswell hire a man he knew to help around the property. He was down on his luck, Pederson told them, and had a criminal record related to his struggles with addiction. Caswell thought it was a good opportunity to help someone get back on their feet. Day disagreed. Eventually, Caswell won, and they agreed to hire the man and give him a place to stay. It was Daniel Burda.

In January 2019, Day’s family in California finally learned he was missing through the media; they were livid. The police tried to reassure them, insisting there was no reason to come to Oregon. The local officers said they were making progress in determining the events leading up to Day’s disappearance, which was true. By all accounts, the decision to allow Burda to move in hadn’t gone well, and in the days after Caswell was hospitalized, Day and Burda’s relationship became volatile. Neighbors reported hearing arguments and described Day as distraught; he wrote a letter to one neighbor claiming that Burda had become violent. Then he approached Pederson about asking Burda to move out. But before Pederson had a chance to help, Day vanished. When police went to question Burda again, he was still at the property, and later they determined that he had been using Day’s bank card. But stealing from a missing old man wasn’t evidence of harm. They decided it was time to put out a bulletin for Day’s car.

They got a hit. Just the day before, the Oregon State Police had pulled over two women more than 100 miles from Phoenix in a car that matched the description. The woman driving told the state trooper that they had borrowed the vehicle from their friend, Dennis Day, but that they didn’t know where he was.

Eventually, Day’s family launched an independent investigation and demanded that the case be turned over to the state police. The flurry of media coverage of the missing Mouseketeer had generated no leads and instead resulted in a lot of sensationalized stories about, as Day had once described similar coverage, how much a former Mouseketeer had “degenerated.” To the alarm of his family, the press focused on the grimmest of details, especially after the neighbors reported an odor coming from the house. It took until April for the department to hand the case over to the state police. Meanwhile, officers arrived with cadaver dogs and searched the home. The canines discovered Day’s body under a pile of laundry. The medical examiner would later determine that several bones had been broken by officers stepping on his corpse in the first searches of the home.

The state police and local investigators questioned everyone again, including Pederson, who had referred Burda to Day and Caswell. Pederson passed a lie detector test. Then the women who had been driving Day’s car were arrested. They pointed the finger at Burda, saying that they had taken the car after a drug-fueled fight in the days following Day’s disappearance. And new details emerged, including one Phoenix officer’s observation that Burda’s hands had appeared to have “battle wounds” when they questioned him in the early days of the investigation. Burda became the prime suspect, but the case moved slowly, impinged by the coroner’s inability to determine the cause of death owing to the advanced state of decomposition of Day’s body. Eventually, Burda was arrested on charges of second-degree manslaughter, criminally negligent homicide, first-degree criminal mistreatment, second-degree abuse of a corpse, aggravated identity theft, fraudulent use of a credit card, and second-degree theft. During questioning, he admitted to shoving Day to the floor and then continuing to use the house when he didn’t get back up. He even described measures he had taken to cover up the smell of death. But so much time had passed and so little physical evidence remained that it was hard to prove that the fall had caused Day’s death or that Burda, who in a court appearance called the charges “messed up,” had intended to harm him.

Everything came to a halt when Burda was deemed unfit for trial and a judge blocked several key pieces of evidence, including Burda’s statements to the Phoenix police and his alleged history of similar relationships with older men. Burda was committed to the Oregon State Hospital for treatment of a “mental disorder.” Meanwhile, the actions of the local law enforcement received further criticism. Day’s family filed a $1.7 million lawsuit in federal court against the Phoenix Police Department and Lieutenant Price alleging that they had mishandled the investigation, which spurred an onslaught of negative, prejudiced media attention and caused them trauma.

In the 1971 Rolling Stone interview, Day had described how after being cut from the club’s cast in 1957, he had felt trapped, unable to either embrace or escape the title of Mouseketeer, especially as the show first went into seemingly endless syndication and then was recast for subsequent generations. In hindsight, he said, he probably should have just grown up like a regular kid instead of being on television. While his time in the club was during a very different era, the pressures on Disney cast members of today seem largely unchanged. Other young stars—Britney Spears, Selena Gomez, Miley Cyrus, and Shia LaBeouf—have experienced their own struggles with success and infamy. Their stories have echoed Day’s sentiments about the high cost of standing in the limelight. Some things, though, have changed. Today’s young stars have the benefit of predecessors like Day, whose insistence on being accepted as an authentic individual rather than a commercial commodity paved the way for them to publicly claim their unique identities and take on issues of mental and physical health. Disney, now in its 100th year, is also evolving, heeding calls for change. Day would likely be proud of the company’s Florida employees for urging the company to speak out against the Don’t Say Gay bill.

It’s said that Walt Disney never really liked the idea of the Mickey Mouse Club, but of all the Disney products and offshoots, the Mickey Mouse Club is one of the most enduring and iconic. And when Walt opened Disneyland in 1955, he did it surrounded by the country’s newest superstars, the Mouseketeers. The park, he said, was “dedicated to the ideals, the dreams and the hard facts that have created America—with the hope that it will be a source of joy and inspiration to all the world.”

Day lived both the dreams of Hollywood and the hard facts of American life. He was a cultural influencer before we had a word for influencers, an early and vocal advocate for LGBTQ rights, and a challenging and beloved instructor and director, but he spent most of his life trying to grow beyond, and reconcile with, his time as a Mouseketeer. In many ways, his life speaks to the value of staying true to oneself, regardless of the wishes or machinations of powerful economic or cultural forces. And his death—especially given his living situation—might serve as a reminder of the urgent need to help artists earn sustainable wages and to provide them with social safety nets in retirement. In 2019, Abigail Disney insisted that “the people who contribute to [Disney’s] success also deserve a share of the profits they have helped make happen.” Perhaps if Disney had embraced that notion back when the Mouseketeers were helping build it into the media giant it is today, the sad saga of Dennis Day might not have happened.

CODA

In 2022, Burda was found to be fit for trial, and the Oregon Attorney General’s Office, in conjunction with the state solicitor general, succeeded in appealing the prior evidentiary ruling. The jury will now be allowed to hear evidence regarding his criminal history, previous relationships with older men, and admission of harming Day. In April 2023, Burda pleaded guilty to a first-degree criminal mischief charge for removing his GPS monitor and throwing it into a creek. He faces 13 charges, including manslaughter, criminally negligent homicide, abuse of a corpse, and identity theft, in connection with Day’s death. His trial is likely to begin in January 2024. The civil lawsuit was rejected at the federal level and refiled in the State of Oregon. That trial could begin as early as May 2024.•

Ruby McConnell is a writer and geologist who writes about the intersection of the natural world and human experience. She is the author of the critically-acclaimed outdoor series A Woman’s Guide to the Wild and A Girl’s Guide to the Wild and its companion activity book for young adventurers, and Ground Truth: A Geological Survey of a Life, which was a finalist for the 2020 Oregon Book Awards. She lives and writes in the heart of Oregon country. You can almost always find her in the woods. She's on Twitter at @RubyGoneWild.