Excerpted portions in this article are reprinted by permission of Newmarket Press,

www.newmarketpress.com

, publisher of 1000 Dollars & an Idea: Entrepreneur to Billionaire by Sam Wyly, Copyright © 2008 Sam Wyly.

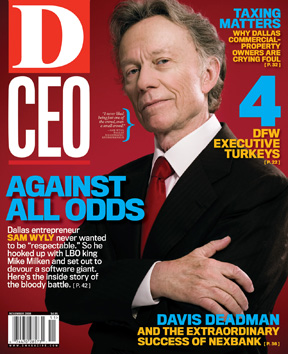

portrait by Sean McCormick

|

| DALLAS BUSINESSMAN SAM WYLY: “I never liked being just one of the crowd, even a small crowd.” |

Dallas entrepreneur Sam Wyly has founded or grown a number of dynamic companies over the years, including Michaels Stores, Maverick Capital, and Green Mountain Energy. But few have been as dynamic as Sterling Software, which Wyly co-founded with Sterling Williams in 1983 with a personal investment of $2 million. After gobbling up 35 small and large companies over 17 years, Sterling was sold to Computer Associates for $4 billion in 2000, at the height of the tech and telecom boom. In this article, excerpted from Wyly’s memoir 1,000 Dollars & an Idea: Entrepreneur to Billionaire, the Louisiana-born businessman recalls how Sterling battled to make its most ambitious acquisition—one that served as a template for all the others that followed.

By the mid-1980s, the computer boom was taking the country by storm. Sterling Software was doing so well—providing businesses with strong storage management and data communications products—that we were among the top 50 software makers in the country. Three years after start-up, we had $12 million cash in the bank and $20 million in revenue, and the stock market valued us at around $30 million. The brokers and the analysts were saying that we were respectable.

Who wants to be respectable?

I never liked being just one of the crowd, even a small crowd. In the competitive marketplace, if you’re going to pour your heart and soul into a company, then you want that company to rise to the top, because being an entrepreneur isn’t about making money. There are easier ways to make money. Being an entrepreneur is about creating an enterprise, it’s about building, it’s about winning, and it’s about the quality of the journey—my definition of success.

We wanted to be one of America’s fastest-growing companies, to be one of the best investments, and to be a good place to work. I wanted to create more millionaires. I wanted people to whistle when they thought of Sterling Software, the way you whistle when you see flawless design. I wanted the feeling of quality that Mama exuded when she held up a cherished piece of her silverware and said, “It’s sterling silver.”

To make that happen, you first have to see the opportunities. And they don’t always have “opportunity” written across the front of them, like a college sweatshirt—sometimes you need to be “bodacious.” That is what Texas oil wildcatters call it—“bold” and “audacious” put together—and, of course, it has to be said with a Southern drawl. Bodacious ain’t easy, and it needs to be accompanied by a lack of fear because sometimes creating companies can get real scary.

|

In 1982, Sterling Williams was wandering through the crowded halls of the annual computer convention in San Diego when he ran into Werner Frank. Werner was then about 60 years old and thought of himself as semi-retired, but he knew software well, having earned his stripes working with the legendary computer scientist John von Neumann, a refugee from Nazi Germany. A mathematical genius, Werner worked on secret U.S. Army “command and control” computer projects and was one of the founders of Informatics, in California’s San Fernando Valley. They had about $200 million in annual revenues—enough to make them one of the three biggest software companies in the country. Running into each other at the convention, Sterling and Werner talked for a long time about the good old days, and what was going on in the industry, and about their mutual discomfort with Werner’s partner, Walter Bauer, the CEO of Informatics.

Bauer was a man with white hair brushed back impeccably and large-framed glasses, a few years older than Werner, who looked more like an actor sent from Central Casting to play the part of elder statesman. He was difficult, having earned the reputation both inside and out, for autocratic and stingy management. To most, he broadcasted an air of intellectual superiority, but his insecurity quickly surfaced when in the company of someone as amazingly brilliant as Werner Frank. Disenchanted with Bauer, Werner told Sterling that he was leaving Informatics to become a consultant. Instantly, Sterling said, “I want to be your first customer.”

Informatics was founded as a computer outsourcing firm but expanded into software products. They had done an IPO, then sold the company to the insurance giant Equitable Life in what proved to be a dysfunctional marriage, and then IPO’ed again. As a result, the company had lots of cash in the bank and no debt. But Informatics’ stock price was not only depressed, it was also erratic—something shareholders hate. The closer I looked at it, I could see good businesses buried inside. For example, they had an excellent report writer for the IBM/360 called Mark IV, but they had never followed it with the next software product. There was no encore. I wanted to own Informatics, but they were 10 times bigger than us. No one in the industry could imagine a takeover of a company 10 times their own size. Bauer knew that Werner was working with us, so he called him to see if we would be interested in buying a software product that he wanted to divest. Sterling agreed to meet Bauer over dinner in Los Angeles.

|

The two sat and talked like old friends for a while, until Bauer shifted the conversation. He asked Sterling, “What would you boys think if Informatics was interested in taking over your company?”

Sterling’s first thought was, “Not a hell of a lot,” because here was a guy we were looking at, who was looking back at us, and now is getting ready to buy this $20 million company out from under us before we even had a chance to get going. His second thought was more to the point: “Bullshit!” That is when Bauer upped the ante. He told Sterling, “The best thing about us taking over your company would be that you’d run it, plus the rest of Informatics, reporting only to me.” Sterling was ambitious and loved being captain of his own ship, but he kept thinking that this wasn’t very ethical.

As soon as he got back to his hotel room, he faxed me this handwritten note: “Sam, I met with Walter and here is what he said: It turned out he didn’t want us to buy his products. He wanted to buy our products. Then he really wanted to buy our company. But he also said that he would have me run all of it, and I’m not even sure he wanted to buy the company. I think he was really recruiting at the end of the day. So what do you think we ought to do? Sterling.”

|

| HERE, THERE, EVERYWHERE: Sam Wyly, left, with then-President Richard Nixon and Joe Kirven, right, of the President’s Advisory Council on Minority Enterprise. photography courtesy of Sam Wylie |

I resented Bauer’s bad behavior, while cherishing Sterling’s loyalty. Where I grew up, they used to hang horse thieves. I wrote three words on the same memo and faxed it back to Sterling: “Let’s buy them!”

The phone rang. Sterling said, “Are you serious?”

I said, “Absolutely.”

Bauer had declared war, so instead of retreating, or mounting a hasty defense—everyone who ever played football knows that sometimes the best defense is a good offense—we were going to take the war right back to him.

Bauer’s words served as the kick in the butt to push me down a path I had been hankering to take anyway. I had been impatient to move Sterling Software up the food chain. I believed Informatics was ripe for picking, and that we could make it into an extraordinarily good fit. What’s more, I was beginning to realize that the two factors that made such an acquisition appear impossible—their whopping size advantage over us and the conventional wisdom on Wall Street that hostile takeovers did not apply to the computer software industry—were not insurmountable.

Bodacious? Yes.

Impossible? No.

|

| Wyly with Swiss investor Walter Haefner, center, and electronics-engineer Glenn Peniston, right, at a Cedar Hill transmission tower for Wyly’s Datran, or Data Transmission Co. photography courtesy of Fortune Magazine/Hans Namuth |

MILKEN’S WAY

I knew this was going to get nasty. Hostile takeovers were simply not done in the software industry because the conventional wisdom was that such a takeover would drive away all the talented and knowledgeable people, leaving nothing but an empty corporate shell of a company. Software developers were a rare breed, and if you had a good group, you were dependent on them. It had never been done, so the law according to Wall Street went, “You can’t go hostile to a company where the assets go down the elevator and out the front door every day.”

I agreed on who the assets were, but saw that Wall Street missed something big. From the first time I heard the term “hostile takeover,” my reaction was, “Hostile to whom?” The way I saw it, most often it’s hostile only to the entrenched powers, the top executives and board members. I kept asking myself, “What if you treat the employees well? What if you create a better work environment? What if you build a better business? Can you be a conqueror and a liberator at the same time?” Both roles appealed to me, so we started putting together an army to do battle.

The first thing to do was buy some Informatics stock. This meant, even if we lost the bid, we would still make money off the run-up of the share price—which would likely happen as soon as news got out and another buyer proposed to pay a higher price. We began by buying stock quietly on the open market. Going after a company 10 times your size means you need a lot of leverage. We did not have enough equity, so no bank lender was going to back us. I knew the one and only place that would appreciate what we were trying to do, and could assemble the leverage we needed, was Drexel Burnham. I phoned Peter Ackerman and set up an appointment with him and his boss, Mike Milken.

By the time Mike hit 40, in 1986, he was being called every name under the sun, from “economic genius” to “the most powerful man since J. P. Morgan himself” to “the man who epitomizes the decade of greed,” but most of all he was being called “The Junk Bond King.”

A brilliant guy who had graduated summa cum laude from Berkeley, Mike, while getting an MBA from the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, took the bus to Manhattan to work for a Wall Street brokerage that eventually became Drexel Burnham. By 1973, he had created their non-investment-grade bond department. His ability to bring in 100 percent returns on investment made him a multimillionaire by his 30th birthday.

Over the next 10 years, he and a small team literally invented a new class of high-yield debt, and with it Mike and his team almost single-handedly fueled the leveraged-buyout boom during the 1980s. That wasn’t what Mike had set out to do in the 1970s, however. His bonds paid very high returns because of the perception of a very high risk of default.

|

| Wyly, left, with his brother Charles Wyly at the Dallas headquarters of University Computing Co., or UCC. photography courtesy of Sam Wylie |

Although these bonds eventually became known as a favored tool for leveraged-buyout specialists in the 1980s, Mike’s original goal was different. He wanted to provide access to capital for growing companies that needed financing to expand and create jobs. Most of these companies lacked the “investment-grade” bond ratings required before the big financial institutions would back them. Mike knew that non-investment-grade (aka “junk”) companies create virtually all new jobs, and he believed that helping these companies grow strengthened the American economy and created good jobs for American workers.

It was by studying credit history at Berkeley in the 1960s that Mike developed his first great insight. He found that while there could be significant risk in any one high-yield bond, a carefully constructed portfolio of these assets produced a consistently better return over the long run than supposedly “safe” investment-grade debt.

Mike’s competitors—Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and Credit Suisse First Boston, the old oligopolies of the syndication business—labeled them “junk bonds” to disparage Mike’s brainchild. He was not a member of their white-shoe club and they were not going to take his act lying down. Of course, today Goldman, Morgan, and Credit Suisse make much of their money off the same kind of bonds, and Mike’s former protégés run most of that business for them.

The first time I walked in his door, Mike was just getting started and had only 12 people working for him. Once he got rolling, the fees he brought into Drexel grew from $1.2 million to over $4 billion. Mike moved his high-yield bond business from New York to California so his kids could know their ailing grandfather, who was battling cancer. But his team was a shop within a shop; they were still at Drexel, sort of, just taking a bigger chunk for themselves. Then Rudy Giuliani, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York in 1989, charged Mike with racketeering and fraud and indicted him.

Most of the activities they charged Mike with had not previously been considered crimes, and prosecutions of that kind are no longer done. Giuliani loved the high-profile case because he saw it as his ticket to becoming mayor of New York and eventually a presidential candidate. Mike agreed in a plea bargain to six securities and reporting violations and was sentenced to 10 years in prison. He served 22 months.

I’d watched over the years as Mike and others put deals together, first for $20 million, then for $100 million, then for $1 billion. They were brilliant entrepreneurs who completely changed the playing field for us smaller guys. Mike was the one who enabled the Davids to beat the Goliaths; he developed financial leveraging tools for them, just like David’s slingshot. He said, “Money’s not scarce; good managers are scarce.” He got us the capital to take on the big boys.

AN ARMY OF MY OWN

I personally found the anything-is-possible business mood created in the ’80s exhilarating, similar to what my pioneer corn-farmer, cotton-planter grandfathers must have felt when their covered wagons reached the deep, rich soil of the Mississippi River Delta land.

And I was hankering to own Informatics.

Being outgunned 10 to 1 meant I needed an army of my own. The minute that Mike and Peter got on board (Drexel signed up for $140 million), the fight was on. In five days, we bought enough shares to put us at just under 10 percent.

The day we published to the world what we were doing, I explained it face-to-face to Bauer. I’d heard the expression “pale behind his suntan,” but I’d never really known what it meant until that moment. I saw the blood drain from Bauer’s face. “We own 9.9 percent as of yesterday,” I told him, “and we’re gonna buy the whole company, so why don’t you and I work out doing it in a ‘friendly’ way?”

That was at the end of breakfast. Bauer was not going to let these poco loco upstarts from Texas have his very own company, and so things turned nasty quick.

In fact, the software industry (the old hands, not the young bucks) was in an uproar. The industry was very insular in those days—everyone at the top knew everyone else at the top—and many people thought what we were doing was just terrible. Not the gentlemanly thing to do. Some were afraid of change and did not understand that a takeover could mean liberation. Hand-in-hand with being audacious means you can’t get paralyzed about what other people say about you, so we moved our executives from Dallas to a hotel in Los Angeles and set up a war room. We brought in computers and multiple phone and fax lines.

Mounting a takeover, I wasn’t always sure what to expect, and it surprised me when people came out of the woodwork with some service to provide in exchange for a fee. It became a feeding frenzy of the professional classes. We had to hire lawyers, accountants, and press relations folks, and they would all cost a lot whether we won or lost. I figured that if some competitor outbid us, at least we’d make enough profit on our 9.9 percent to pay the expenses.

To fight back, Bauer ran full-page ads in The New York Times saying what a bad guy I was.

In the middle of this, Bauer and a few Informatics executives tried to put together a management buyout. They tried to find another company to come in as a white knight, to save the company from us Genghis Khans.

We made our first bid when Informatics’ shares were hovering around $17, and invited the Informatics incumbents to discuss their own attempted buyout. Bauer led them into the room, thinking he could walk away with the company. But when Peter Ackerman spelled out to them how ironclad our financing was, and it sank in for them that no one had committed that kind of capital to them, or would commit it, they gave up.

No sooner had that happened when an investment company, Maxxam, announced that they had been buying Informatics shares. Whether they were really interested in owning the company or just trying to make a quick buck as arbitragers, I couldn’t tell. But it definitely added to the drama.

Maxxam filed the day after Informatics rejected our bid, and now the share price was up to $24 and they announced their bid for Informatics.

What I didn’t know was that Maxxam’s bid was an illusion. They were just trading the stock.

That only served to up the ante for Bauer, since we could sell our 9.9 percent toehold for profit. If we went away and nobody else came in to buy the company, the price would drop from $24 to $17 or $15 or $12, or maybe even lower. No one knew where the bottom would be.

Bauer had a couple of independent directors on his board, and one of them, Fred Carr, kept saying to Bauer, “I don’t hear any other bids. Are you going to buy it yourself? If so, do it.”

He couldn’t do it, because capital seeks good managers and avoids the opposite.

Bauer called in his top managers and told them, “I want everybody to put in some of your savings.” One of his best managers thought to himself, “Under this leadership? You’ve got to be kidding.”

From start to finish, this whole drama took about six months. We wrote the checks and only then realized that we had done what no one else had ever done in the software industry. Little Sterling Software had gobbled up a giant and was now a major player.