Analyst or Moralist?

The increasingly political nature of cultural criticism does a disservice to the arts, to artists, and to criticism itself.

“There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book,” Oscar Wilde wrote in the preface to his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, “books are well written or badly written, that is all.” Wilde was correct. Moral considerations should be suspended when evaluating a work of art. A novel may contain unpleasant characters, but it does not follow that the novelist himself is immoral for creating those characters in the first place. The function of a flawed or immoral protagonist may be to remind us of our own corruptible natures, to introduce complexity to a story’s people and dilemmas, or simply to illuminate humanity in all its variety and peculiarity. A novel filled with moral goodness and clarity will not be not true to life.

“All art,” Wilde also remarked, “is quite useless.” This pithy aphorism reminds us that art is intended for aesthetic pleasure not practical utility—it is an end in itself and not an instrument of moral instruction or politics. The very worst art, Wilde believed, is that which kowtows to rigid orthodoxies and sacrifices the autonomy of the artist in order to deliver a helpful message of some kind.

In Wilde’s time, moralistic objections to art usually emerged from the conservative and religious Right. In our own age, artists must contend with demands from the progressive Left that art bend the arc of history towards social justice. Activist critics insist upon purity of language and proportional representation of minority demographics in ways that undermine freedom of thought and expression. But the micromanagement of language and the misconception of life as a competition for recognition are not conducive to the creative process. How can the imagination flourish freely in such a climate?

Unfortunately, the people who seek to remake art in this way hold positions of power in precisely those institutions where creative freedom and the elevation of the individual voice ought to be abundant. The works of those who espouse an unambiguously progressive worldview are celebrated while an appreciation of our cultural inheritance is increasingly scarce or even scorned. This destructive ideology is radical, simplistic, and incoherent—a perversion of French Rationalism and German Idealism that attempts to impose a false teleology upon our shared culture. It overlooks the particular and the concrete in search of the abstract, which moves culture away from organic expression towards something closer to agitprop, unrooted in experience and the spontaneity of imagination. This development, well-meaning though it may be, misunderstands the true nature of artistic creation.

“Goethe’s garden,” George Steiner once noted, “is a few thousand yards from Buchenwald” and “Sartre regarded occupied Paris as perfect for literary and philosophic production.” To which he added, “When we invoke the ideals and practices of the humanities, there is no assurance that they humanise.” Kant, Euripides, and Chaucer do not necessarily make their readers better people, nor does involvement in artistic production make a person more virtuous. Caravaggio murdered a man in a brawl and G.K. Chesterton was an antisemite. Their behaviour does not diminish the beauty and profundity of the work they produced. To appreciate their creative talents does not require an endorsement of their personal politics or conduct. Caravaggio’s startling use of light and Chesterton’s sharp and lucid prose draw us into their work regardless of the creators’ moral shortcomings.

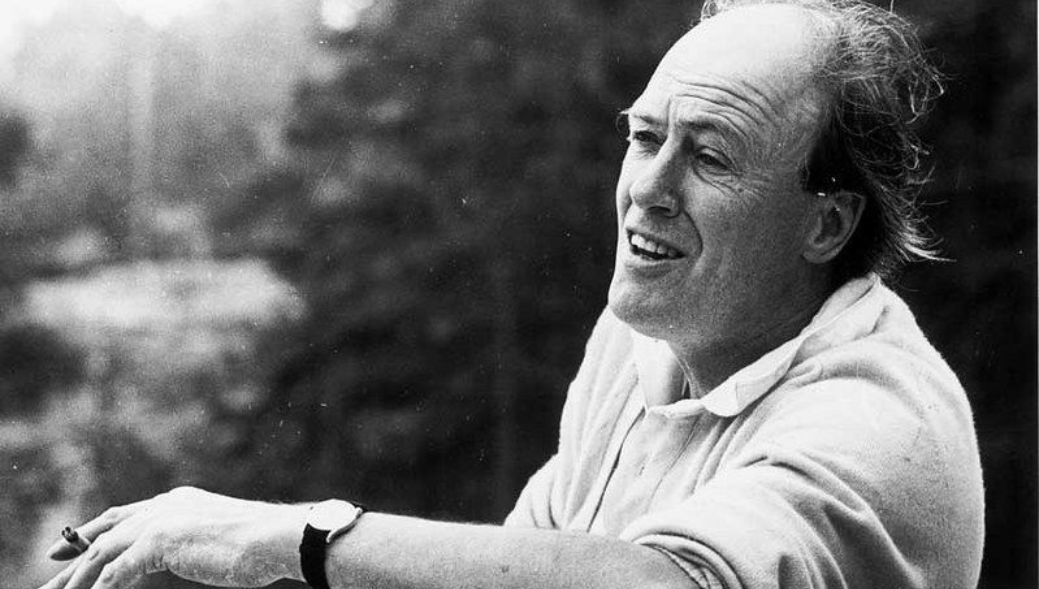

Harold Bloom (who was Jewish) spoke of the ambivalence he felt reading Chesterton:

Chesterton goes on puzzling me, because I find his critical sensibility far more congenial to me than that of T.S. Eliot and yet his anti-Semitism is at least as ugly as Eliot’s.

While Bloom had personal reservations about the man, he understood his obligations as a critic. Works of culture may move us in complex ways but they should not be asked to transform moral character. It would be quixotic for an artist to believe that he can convert the reader to a particular point of view on a whim. A novel by Dickens or Tolstoy may persuade us of the plight of their characters but they do so without resorting to didacticism. That is not to say that didactic culture is without value or somehow inherently inferior, but those works without any merit beyond the social or political message they wish to convey don’t really qualify as culture at all.

Asked about the homoeroticism in his novel The Picture of Dorian Gray at his trial for gross indecency in 1895, Wilde defended it as a purely artistic work. Art assumes a separate life from that of its creator, just as Basil Hallward’s painting of Dorian Gray does. Wilde’s preface did not appear in the first edition of the novel—it was written as a response to critics who misused their authority to indulge in self-righteous displays of moralism. One of them described the book as a form of “moral and spiritual putrefaction.” As a result, short passages were removed from subsequent editions.

In the opening pages of Dorian Gray, Wilde vividly describes Basil Hallward’s studio as “filled with the rich odour of roses” and the “heavy scent of lilac” carried through the open door by a light breeze. Wilde’s use of language here is not just setting the scene, it is creative for its own sake. The portrait on which Hallward is working, Wilde tells us, captures a “gracious and comely form” with “finely curved scarlet lips” and “crisp gold hair.” The character is placed on a pedestal so that we may admire this “young man of extraordinary personal beauty.” The prose may be homoerotic, but his moralising opponents failed to appreciate that it is also much more than that. The proper task of a critic is to identify the elegance of the novel’s heady aestheticism rather than simply scold its effrontery to prevailing sensibilities.

The critic underwrites the imaginative power that an artist brings to bear on what it means to be human. Rather than resorting to grandiose theories and pseudoscientific methods, the critic’s job is to elucidate the work of the artist with care and sympathy. The task of the humanities, after all, is to transmit the achievements of humanity across generations. The critic should be a disinterested analyst, willing and able to suspend his own feelings, convictions, and beliefs when assessing art and culture.

But today, critics are preoccupied with “problematising” the back-catalogues of artists and scrutinising a work’s social or political message. These priorities have in turn affected the kind of work that gets produced. Charlie Higson’s series of Young Bond novels seem to have been designed to repudiate the moral complexities of Ian Fleming’s brutal womanising protagonist. One of the books contains this passage, clumsily inserted to reassure the reader of the author’s left-liberal bona fides:

Birkett was an ex-Tory MP, famous for promoting covid/vaccines/mask-wearing/5G conspiracy theories, which had spilled over into the usual anti-immigrant, anti-EU, anti-BBC, anti-MSM, anti-cultural Marxist, Climate Change Denial pronouncements.

The politics is heavy-handed, the syntax is convoluted, and the combination is only likely to be appreciated by someone who wants to have their own left-liberal sympathies flattered. The condescending and paternalistic language resembles an editorial written for the purposes of political education rather than a thoughtful exploration of the human condition.

In Amazon Prime’s film Red, White, and Royal Blue, the message often suffocates the drama. The story deals with a homosexual romance between a spare to the British throne named Henry and Alex, the Hispanic son of the president of the United States. The two men love one another but their relationship is undermined by the stuffy conservatism of backward institutions. In addition to being gay, Henry and Alex both feel victimised in other ways. Henry feels like an outsider who can never play a full role in the institution into which he was born. Alex’s Hispanic surname and ethnicity, meanwhile, lead him to believe that he is unfairly treated by American society, the advantages of his social position notwithstanding. Alex complains that Henry will never understand his grievances because Henry is rich, white, and male. The scene is unedifying, subordinating the emotional drama to a contest of intersectional oneupmanship between two indisputably privileged people. This kind of sermonising occurs throughout the film, including one character’s lofty description of the senior staff at Buckingham Palace as “wrinkled white men.”

Emerald Fennel’s film Saltburn, on the other hand, offers a more irreverent and complex indictment of class privilege that seems to have been inspired by a combination of Evelyn Waugh’s 1945 novel Brideshead Revisited and Pasolini’s 1968 film Theorem. It is not exactly apolitical, but nor does it lecture us with the instructive sanctimony that Red, White, and Royal Blue employs. The film’s message—that the rich are spoiled, vapid, arrogant, and vain—is subordinate to the amorality of the psychodrama and the demands of its twisty narrative. Fennel does not have to spell out the fact that the characters are morally inept—she just lets us watch how they behave.

Attempts to engineer culture for the greater good have invariably been paternalistic and censorious. Theodor W. Adorno and Max Horkheimer argued that mass culture ought to be treated with the same suspicion as organised religion—like a new opiate for the masses. The Frankfurt School believed that popular culture corrupts and perpetuates false consciousness. If revolution could not be achieved by overthrowing capitalism, then culture would have to be dismantled instead. This idea of mass culture as an agent of corruption and indoctrination is reinforced by advocates of “media effects” theory, who erroneously identify a causal correlation between media consumption and consumer behaviour. The people therefore need to be rescued from culture’s corrupting influences.

F.R. Leavis was also suspicious of mass culture, but not on Marxist grounds. He lamented a decline in moral standards and believed that society was succumbing to phoney emotionalism and a burgeoning materialism. The spiritual had been exorcised and industrialisation had tainted the masses’ ability to appreciate nature, a concern the Romantics had expressed from the late-18th century onwards. A sonnet by Wordsworth, he said, brought warmth and soul to the industrial city, where instrumental rationality and the pursuit of profit were paramount:

This City now doth, like a garment, wear

The beauty of the morning; silent, bare,

Ships, towers, domes, theatres and temples lie

Open unto the fields, and to the sky;

All bright and glittering in the smokeless air.

Leavis praised Wordsworth’s ability to channel ideas about the human experience that were non-mechanistic and sensitive to the individual. But Leavis was disdainful of contemporary mass culture, which he believed did nothing to elevate the masses to a realm beyond themselves.

Leavis’s dismissal of popular culture was indicative of a broader concern about value and the distinction between high and low culture. But to look at culture in this way encourages a reductivism that assumes all high culture is good and all popular culture is bad. The history of film and popular music shows that this is demonstrably false. High and low are not respectively synonymous with good and bad, although there are good and bad examples of each. Matters of value and judgement are for the most part subjective but that should not be a reason for the critic to abandon them entirely. Rather than embrace relativism, the critic should make the effort to argue why the work under discussion is worthy of our attention in the first place.

Cultural Studies had the potential to enrich our understanding and assimilate the great artistic achievements of the 20th century—particularly the cinematic achievements—into the canon. Unfortunately, the discipline was tainted early on by political correctness and a repudiation of Western culture’s entire inheritance. Value judgements were set aside in favour of a fealty to ideas that saw dominant culture as part of a superstructure that maintains the capitalist system. The notion that culture is separate from politics was rejected entirely.

A commitment to the practice of value judgement is for the critic a far more worthwhile enterprise than submitting to a relativism, the logical end of which, the Marxist critic Terry Eagleton speculated, is a world where graffiti is deemed just as valuable as Shakespeare. To insist upon distinctions in quality often results in accusations of snobbery, as Martin Scorsese discovered when he spoke dismissively of superhero blockbusters. The films Scorsese has championed are those that took risks with their form and content and did not set out to reap huge financial rewards. This distinction elicits accusations of elitism because canonical films were made for niche middle-class audiences and cinéphiles. But does this really require us to pretend that there is no qualitative difference between a film like Ingmar Bergman’s Persona and a Marvel spectacular?

Pierre Bourdieu argued that matters of taste are not objectively definable, they are merely social constructs. There is a kernel of truth there, but the idea that artistic value is simply a matter of arbitrary consensus is unpersuasive. Is there no such thing as transcendent beauty? Bourdieu is French, and French culture is somewhat constrained by the académies, but France has produced wonderful music, literature, painting, film, and food nonetheless, all of which can be appreciated by outsiders.

If taste is merely a social construct, why are Michelangelo’s David, Shakespeare’s King Lear, and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 still widely revered? Voguish ideologues argue that Western society elevates the achievements of dead, white men above others, but this is not particularly convincing either. Courbet, Van Gogh, and Pollock were all white males but they were either ridiculed or ignored during their own lifetimes. Great works often go against the grain, and all progress depends on dissent. Courageous and thoughtful works that strive to understand and interpret the complexities of the human experience in all its joy and anguish will be the ones that best stand the test of time. Only a very small number of works will do so successfully, and they are worth treasuring for that very reason.

“Persons of genius,” John Stuart Mill argued, “are always likely to be a small minority; but in order to have them, it is necessary to preserve the soil in which they grow. Genius can only breathe freely in an atmosphere of freedom.” Even for authors who produce work under tyranny and oppression, the best and most enduring art will be true to our shared condition and not consumed by the noise and folly of the moment. The sympathetic critic should recognise that while an artist lives and works within a particular social and political structure, this is not the same as destiny. It is his solemn task to understand and describe the relationship between the artist, the art, and the experience of being human.