For many years, Israel believed that Eli Cohen was captured due to the fact that Syrian intelligence managed to intercept his correspondence with Mossad headquarters in Israel. However, testimony which appears in my book, “Eli Cohen – Open Case” shows that there is actually very little chance that the Syrians succeeded in locating the signal of Cohen’s communication device.

Documents and testimony from the head of Syrian intelligence and the testimony of an intelligence officer who broke into Cohen’s apartment indicate that the Syrians carried out constant physical surveillance of Cohen. How, then, was Israel’s man in Damascus really captured?

Recruitment

The decision to recruit and train an agent to be stationed in a target country (Egypt, Jordan or Syria) was made in 1958, not long after military intelligence failed to identify the Egyptian army’s infiltration into the Sinai Peninsula. Indeed, the head of Military Intelligence was dismissed as a result. This failure stemmed from a decision made by one of the officers in the IDF listening unit to not pass along information regarding Egyptian armored units crossing the Suez Canal. Military Intelligence decided there was a need to significantly improve its ability to identify states of high alert and the movement of forces in unfriendly Arab countries. To this end, it was decided to plant a number of agents in Arab countries who would report on military movements and preparations. As part of this directive, an operative was recruited to be stationed in Damascus.

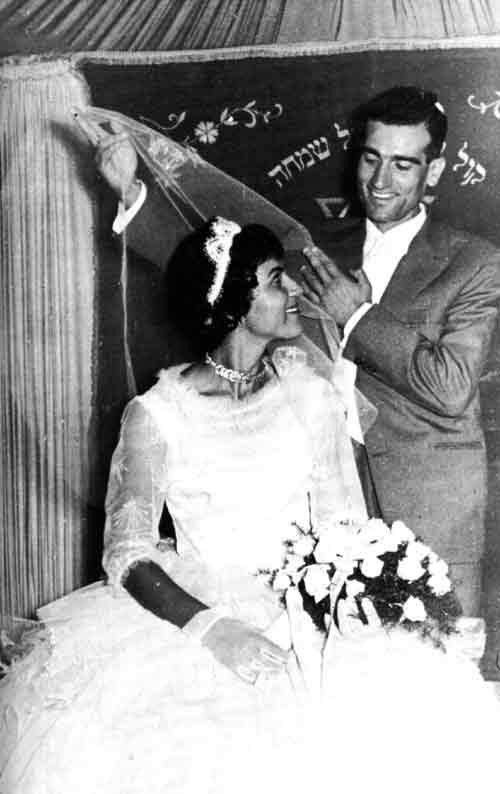

The recruitment of Eli Cohen to Unit 188, a military intelligence unit dedicated top operations beyond Israel’s borders, happened by coincidence. In September 1959, Cohen sent a Rosh Hashana greeting to Shlomo Millett, the interviewer who had previously disqualified him from serving as a spy. As a result of this greeting card, the question of Cohen’s candidacy was raised again. This time, as there was an immediate demand, Cohen was allowed to begin the recruitment process with two other candidates.

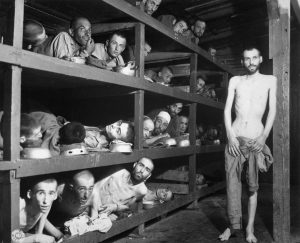

Finally, Cohen was chosen and he began learning his craft at Israel’s “School of Espionage”, which at the time consisted of only two instructors, Motti Kfir and Nathan Salomon. Salomon began to teach Eli Cohen the most basic skills needed by any spy – how to follow and how to avoid being followed, how to write in secret ink, and other methods of avoiding detection. Among other things, Salomon noticed that his student had an exceptional memory.

Cohen underwent nine months of basic training, which also included photography and film development and instruction in the use of encryption and a Morse code transmitter. Finally, Cohen’s instructors decided that the time had come to craft him a cover story. Cohen became Kamel Amin Thaabet, a businessman whose parents were of Syrian origin, but had immigrated to Lebanon. According to the story, his parents had died one after the other and he was summoned to work with his uncle, a businessman in Argentina.

Cohen landed in the Argentine capital in February 1961 and immediately began learning Spanish with a private teacher. The goal was to be able to speak at such a level as to convince Syrians that he had been living in Argentina for the last 16 years.

Behind Enemy Lines

Upon his return from Argentina, Eli Cohen underwent further training in an operational unit. On January 10, 1962, “Kamel Amin Thaabet” boarded a tourist ship that set out from the city of Genoa, Italy, anchored in Alexandria and, eventually, reached the port of Beirut.

On the ship, Eli Cohen met Majeed Sheikh al-Ard – a figure who would accompany him during his three years in Damascus. Al-Ard was a man of the world; he spoke many languages and was fluent in German. The two met on the deck of the ship and struck up a conversation, during which Cohen told him his cover story. As a rich businessman, looking to invest inherited capital, Cohen expressed his desire to examine the possibility of doing business in his native Syria. Majeed Sheikh al-Ard suggested that after landing in Beirut, Cohen should join him on a journey from Beirut to Damascus. Al-Arad invited Cohen to make the journey with him in his new car and, after a day of rest in Beirut, the pair made their way to the border crossing between Lebanon and Syria.

According to documents from US intelligence, Majeed Sheikh al-Ard was no innocent bystander. Al-Ard was a paid informant for the Americans from 1951 to 1959. Majeed Sheikh al-Ard explained to Cohen that he had a number of friends who could arrange a smooth crossing of the border for a few hundred Syrian pounds. Majeed Sheikh al-Ard called his friend, a Syrian security man waiting for them at the border crossing, while loaning a sum of 400 Syrian pounds from Cohen, a loan that would never be returned. Another friend of al-Ard’s was in charge of customs at the border crossing. Kamel Amin Thaabet (Eli Cohen) sat, drinking coffee at the border crossing as Majeed Sheikh al-Ard’s friends took care of the paperwork and transferred the bags containing the spy equipment that Cohen had brought with him from Israel. When the junior customs officers tried to open the suitcases, their boss scolded them loudly, “They’ve already been checked!” lied the supervisor. This was how Eli Cohen arrived in Damascus without so much as a search of his personal effects.

Five days after arriving in Damascus, and having already managed to rent an apartment, Eli Cohen transmitted his first message back to headquarters in Israel – I have arrived safely.

The Arrest

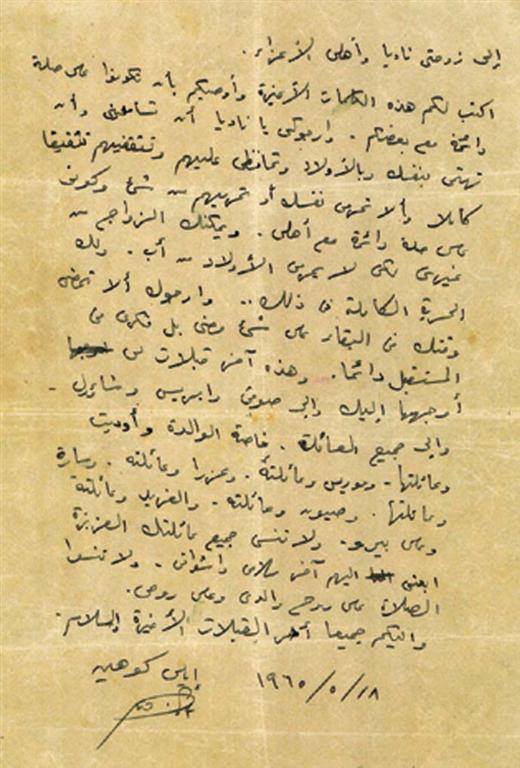

Eli Cohen served in Syria from January, 1962 until his arrest on January 18, 1965.

According to the head of Syrian intelligence, the Syrians began suspecting Cohen when they learned of his interactions with “a man of suspicious ties.” The officer went on to explain that following Cohen’s arrest, a Syrian citizen who had helped him cross the Lebanese border and enter Damascus was also arrested. The source was referring to Majeed Sheikh al-Ard – the very same person who accompanied Cohen throughout his three years in Syria.

Eli Cohen left and re-entered Syria multiple times. The fifth instance was on November 26, 1964. Not long before this, the Syrians had captured two American spies operating out the CIA branch in Damascus. One of the spies, Farhan Atassi, knew Eli Cohen. The Syrians, now acutely aware that they were the target of active clandestine operations, monitored the comings and goings of anyone connected to the U.S. Embassy in Damascus.

On December 1st, Cohen met with his friend Majeed Sheikh al-Ard for lunch. During the meal al-Ard told him that a few days earlier he had met with a man named “Rosolio.” He let slip to Cohen that Rosolio was actually the Nazi war criminal, Franz Rademacher, hiding in Damascus.

Eli Cohen’s ears perked up. He feigned disbelief and told his friend that it was not possible that he knew where Rademacher was hiding. In response, Majeed Sheikh al-Ard telephoned Rademacher. Just forty minutes later, Eli Cohen and Majeed Sheikh al-Ard sat in the Nazi war criminal’s safe house. The apartment was only a ten minute walk from where Eli Cohen lived.

The day after the chance meeting, Eli Cohen happily reported to Mossad headquarters in Tel Aviv that he had located a Nazi war criminal. Cohen provided descriptions of Rademacher’s appearance, his exact address and details of surroundings of the safe house. He awaited further orders, but did not receive positive reinforcement from Mossad headquarters. Instead, he was directed to “stop pursuing the Rademacher lead and focus on the mission.”

Mossad headquarters were obviously not aware of the clear and present danger caused by the tripartite meeting. Otherwise, they would have directed Eli Cohen to drop everything and take the first train to Beirut.

US intelligence documents indicate that Majeed Sheikh al-Ard, who once served as an informant for the Americans, tried to continue to be of use to them. He continued to transmit reports to them, enthusiastically reporting the intelligence he gathered from his meetings with the Nazi, Franz Rademacher.

The theory that I have formulated, and which is supported by the documents and testimonials which appear in my book, is that Syrian intelligence was aware of the tripartite meeting that involved Eli Cohen and Rademacher – either in real time or via information they received shortly after the meeting took place.

At this point, it is worth examining how the Syrians would have perceived this meeting.

They noticed Majeed Sheikh al-Ard, who was an informer for the Americans, coming and going through the gates of the U.S. Embassy. The Syrians also knew full and well that “Rosolio” was a Nazi war criminal, up to his neck in espionage.

At this point you must put yourself in the position of the Syrians and ask yourself – what you would do if you witnessed this meeting between a Syrian businessman and two spies? Would you suspect the businessman as well, and put a tail on him? Well, this is exactly what the Syrians did.

The testimonies of Ahmed Sweidani, Head of Syrian Intelligence, and of the officer who broke into Cohen’s apartment indicate that the Syrians had begun to monitor Eli Cohen. Not long after, they decided to break into his apartment and discovered his spy equipment, including his transmitters and receivers.

The story of the break-in and the analysis of the testimonies indicate that Syrian intelligence had no idea that Eli Cohen was a Zionist spy.

The analysis and the various testimonies and documents can be further examined in the book “Eli Cohen – Open File“.