A medieval nun in black Benedictine habit is seated in a small chapel, writing with a stylus on a wax tablet as fiery red flames

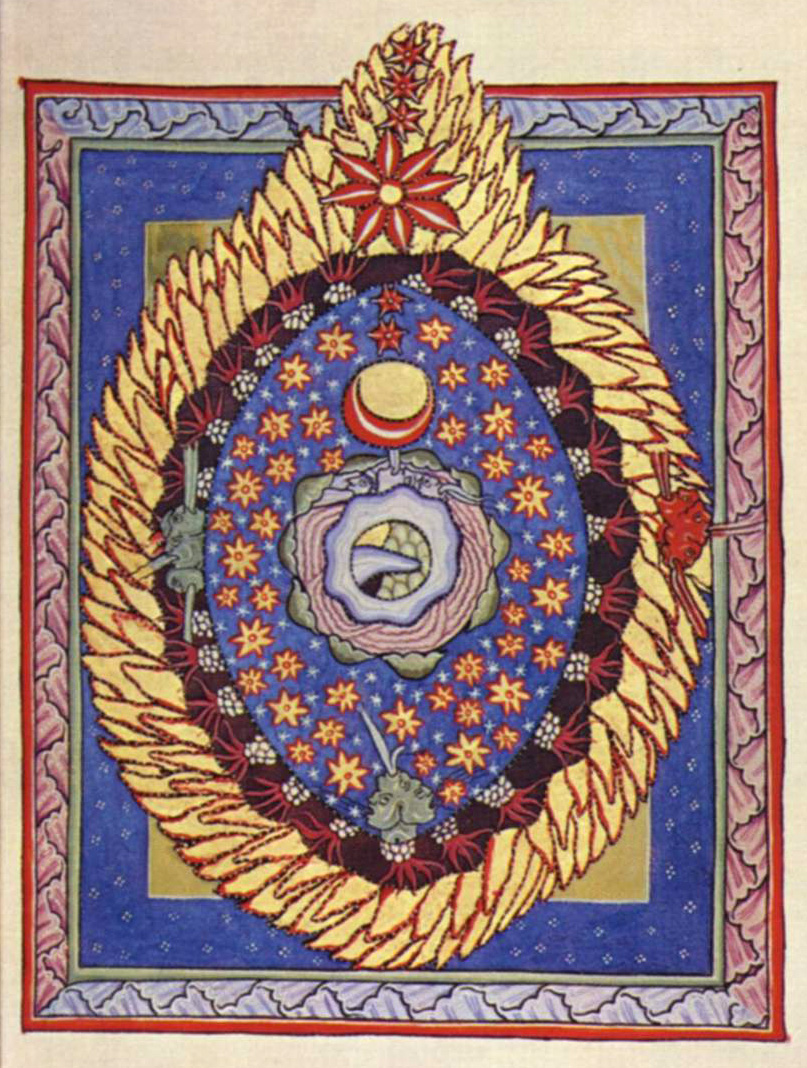

descend upon her, conveying a message from Heaven above. In an adjacent room, the monk Volmar stands witness as the nun, Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179), receives the divine revelation. The Pentecostal scene, colored in vibrant pigments and illuminated with gold, is the first of thirty-five miniatures that illustrate Hildegard’s book entitled Scivias—“Know the Ways.” Accompanied by detailed descriptions of her visionary experiences, the allegorical images offer passageway from the unknowable to the known. The German abbess would have us awaken to a transcendent reality that lies within us and everywhere around us—an unseen dimension as bright as the sun, resplendent as the stars and moon.

Born to a wealthy family of lower nobility in the Rhineland, Hildegard was the youngest of ten children. From the age of three, she began to perceive what she later described as a “reflection of the living Light.” When it became apparent that others did not see the same, she said nothing more of the experience that was “far, far brighter than a cloud which carries the sun.”1 Whether or not her parents were aware of her sensitivities, they tithed young Hildegard to the Church. At the age of eight, she was enclosed in a stone cell adjoining the Benedictine monastery of Disibodenberg and metaphorically buried alive, presumed dead to the secular world.

At Disibodenberg, Hildegard was placed in the care of Jutta, the pale and ethereal young anchoress who was the daughter of a count. The two women were allowed a servant due to their status as noblewomen, but they lived according to the Benedictine rule, which specifies hours of the day for prayer, sleep, meals, spiritual reading, and manual labor. Jutta taught Hildegard to read the Book of Psalms in Latin, sing the Liturgy of the Hours, and play the ten-stringed psaltery. The nuns’ only way of communicating with the outside world was through a small window in the cell, through which food was passed. The complete immersion of a young child into religious life, while unthinkable today, led Hildegard to put her hope and faith in God alone2 and to open her whole heart to the profundity of scripture and the divine mysteries.

The community of women at Disibodenberg grew as more daughters of local nobility were sent to live with Jutta at the hermitage, which remained under the auspices of the monastery and Abbot Kuno. After Jutta’s death in 1136, thirty-eight-year-old Hildegard was appointed superior and soon established herself as a formidable administrator as well as a respected spiritual teacher, skilled herbalist, poet, writer, dramatist, and composer of music. (Her liturgical-style music and breathtaking melodies are widely available today.) A charismatic woman, Hildegard became a champion of Church reform during the Holy Roman Empire’s challenge to Church authority and Europe’s troubled chapter of the Crusades. She sent a flurry of critiquing letters to her superiors and to priests and archbishops. She upbraided the Pope for giving in to politicians, and she warned King Frederich Barbarossa to avoid the idle morals of princes and to cast off all greed.3

Closer to home, the outspoken mystic took issue with the St. Disibode monastery’s use of privileged practices and the monks’ reluctance to allow the nuns more independence and physical space. When Abbot Kuno initially refused her request to establish a new convent, she went over his head to receive approval from the Archbishop of Mainz.4 In 1147 Hildegard would depart Disibodenberg for a temporary settlement before moving again in 1151 to her newly built cloister in Rupertsberg, near the town of Bingen on the Rhine. Much to the Disibode monks’ disappointment, she would take along her wealthy nuns, their dowries, and her growing fame, which followed the resounding success of Scivias, read even by the Pope.

Hildegard was still abbess at Disibodenberg monastery in 1141 when she received irrefutable instructions from God to transcribe what she saw and heard in her visions, which she had long been hesitant to share with anyone other than Jutta. At first she ignored the heavenly command, but when she became severely ill after doing so, she consulted Abbot Kuno. With approval from the Abbot and Pope Eugenius, Hildegard began to record her experiences. Her illness disappeared, and she began what would become, in ten years time, Scivias. Other books followed, including two more visionary texts: Liber vitae meritorum, “The Book of Life’s Merits,” written from 1158-1163, and De operatione Dei, “The Book of Divine Works,” written from 1163-1173.

“I spoke and wrote these things,” Hildegard explained, “not by the invention of my heart or that of any other person, but as by the secret mysteries of God I heard and received them in heavenly places.” While fantastic, her otherworldly visions were more than random apparitions, hallucinations, delusions, or dreams. Perceived while fully awake, these were the experiences of a devout woman who desired, more than anything, communion with the Divine. It was love that led the abbess beyond the boundaries mapped by the human senses. Like a sea turtle guided by the Earth’s magnetic field, she followed another mode of perception—her heart’s wisdom—to the uncharted realm of supersensible reality. Unique not only to Hildegard, the mystical experience lies at the very core of all religions. Brought forth from eternity and translated into words, the divine encounter gives rise to doctrine, ritualism, interpretation, and institutions,6 where the once gleaming vision risks becoming a desiccated and forgotten memory.

Hildegard’s prophetic works span four decades and a dazzling array of theological, scientific, and political motifs. Throughout all is an awakened cosmology; a universe where inner and outer worlds are as one, where the breath of Holy Spirit flows within and without, where humans recognize their divine likeness, live in harmony with all creatures, and abide by the cycles of nature. In the New Heaven and New Earth that Hildegard foresaw, injustices are vanquished and peace and harmony ultimately reign. At the same time, she gave clear warning of the coming calamities—the vices and temptations that lead to folly and the End Times of humankind. Amid visions of the anti-Christ in horrific animal form and an ulcerous devil bound in chains come radiant beings and archetypal symbols—water, fire, wind, Mother Earth, the elements, death and rebirth, the spheres and stars—that offer precious keys to a healed world filled with love, light, and meaning.

In Hildegard’s Book of Divine Works, an illumination known as “Universal Man”7 depicts a human form with arms outstretched in the center of a circle, or “mandala” in Sanskrit. Seen in Christian, Buddhist, Native American, and Aboriginal Australian art, the mandala represents a universe in perfect harmony and wholeness, a cosmos with no beginning and no end. Three hundred twenty-five years after Hildegard conceived her image, Leonardo da Vinci drew a strikingly similar mandala, his iconic Vitruvian Man, which beautifully conveys the sheer perfection of God’s creation. In both illustrations, the human figure appears as a microcosm within the macrocosm of the universe, a noble image of God, and endowed with creative power.

Hildegard’s profoundly optimistic cosmology urges us to revive our innate powers of intuition and rouse from the collective spell of forgetfulness that keeps us dependent solely on the mind’s logic. It is not that Hildegard would have us revert to superstitious or pre-rational thinking; she valued the intellect, was a botanist and a scientist in her own time. She viewed the rational mind as a gift from God but understood that rationality alone could not deliver humanity from all its strife and suffering. Her visions point to another route: a concealed pathway that can be found when we suspend disbelief and contemplate the unseen, almost as an astrophysicist explores the invisible but implied substance known as dark matter.

With both heart and mind, Hildegard beheld the world’s final restoration and the human capacity for transformation. She exclaimed our inherent divinity in saturated colors, bold movements, and figures with non-human elements. Surging red and yellow flames surround a star-filled, egg-shaped universe spinning on a field of blue. There at the center of the cosmic egg’s interconnected layers lies the sacred drama of the human soul with all its strife and suffering. The nine hierarchical choirs of angels that serve God and minister to His beloved creations compose a mandala of dizzying concentric circles. Medieval crenelated towers tilt sideways and upside down in “The Building of Salvation,” while “The Mystical Body” of the Church is a female form with legs hewn of silver mountains and golden wings arising from her shoulders. The current state of affairs may be doomed, but human souls are not in the least.

The abbess who was a brilliant polymath, artist, and composer received no formal education. She professed modesty and insisted her visions and interpretations of scripture came to her by the grace of God. At the same time, Hildegard explained that her illuminations served to expand the understanding of texts she had previously read.8 Beyond the Bible, her writing references the Western Fathers of the Roman Catholic Church—Saints Augustine, Jerome, Gregory, and Bede. She was familiar with the geocentric model of the cosmos that was accepted at the time and knew the Aristotelian theory of the elements and Galen’s four humours.9 Her anatomical descriptions provide hints that she read Constantine the African, the medieval scholar who translated Arabic medical texts into Latin.10 Such books might have been available in the library at the Disibodenberg.

And yet the surreal imagery of Hildegard’s visions and apocalyptic prophecies stands apart from anything she might have found among the shelves of a medieval library. Neither is it likely that the source of her astonishing images can be traced to the auras of migraine headaches, as Charles Singer (1876-1960) once claimed. A scientist and historian, Singer determined that the stars, shining lights, and crenellations seen in Scivias resembled the visual disturbances described by those who suffered migraine attacks. Without benefit of physical findings, “scintillating scotoma” was diagnosed and later confirmed by twentieth century neurologist Oliver Sacks.11 The retroactive assessment seems to discount the context and highly symbolic nature of Hildegard’s illuminations, as well as the millions who experience migraines without comparable imagery.

To insist on a physiological explanation of Hildegard’s visions is to miss seeing them altogether. If you would travel with a mystic beyond the known dimensions, suspend all judgment. Then quiet your mind and allow the intuitive wisdom of the heart to lead. The mystical path is a love story after all—the Song of Solomon’s bridegroom and bride, the outpouring of God’s love for human souls and the souls’ great yearning for God. In Hildegard’s universe, Divine Love exists everywhere at once and within everything. It is the central figure that imbues the Book of Divine Works and a mystery that Hildegard personified: “It had a human form, and its countenance was of such beauty and radiance that I could have more easily gazed at the sun than at that face.”12

Hand in hand with Divine Love (Caritas) is Divine Wisdom, or Sofia in Greek. Another aspect of the Holy Spirit, Sofia transmits the splendor of God through divine intelligence. She is incomprehensible and glorious, like Divine Love, and speaks through the words of the prophets, Hildegard writes, “so that they might pour out streams of living waters over the whole world.”13 If we sit with Hildegard in a state of openness, we can begin to glimpse this reality through her eyes. Look long enough and the visible world governed solely by the mechanistic rules of science falls apart, just as the familiar laws of Newtonian physics collapse in the quantum world.

To transcend the fiction of finite reality is to become a Vitruvian Man—a perfect microcosm within the grand cosmic drama—and to take part in the ultimate salvation Hildegard foretold. “Cooperate in the task of creation,”14 she implores us. With tremendous zeal and steadfast hope, channel love and expectation into your art and countless forms of creative expression. It is the way Hildegard’s “living light” seeps into the hearts of those around us and makes its way out through streams and rivers to the wider world, eventually influencing leaders and enlightening institutions. Illusions disappear, and reality transforms before our wondering eyes when we drink from the well of Divine Wisdom. ◆

1 Newman, Barbara, “Hildegard of Bingen: Visions and Validation.” Church History 54, no. 2, (1985), p. 165. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3167233.

2 Coakley, John Wayland. Women, Men, and Spiritual Power: Female Saints and Their Male Collaborators. Columbia University Press, 2006, p. 52. Google books. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Women_Men_and_Spiritual_Power/402rAgAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=far%20brighter.

3 Book of Divine Works, Matthew Fox, editor, Bear & Company Inc., 1987, pp. 289-90.

4 “Rupertsberg | Monastic Matrix.” Arts.st-Andrews.ac.uk, arts.st-andrews.ac.uk/monasticmatrix/monasticon/rupertsberg.

5 Hildegard et al. Scivias, Paulist Press, 1990, p. 60.

6 Steindl-Rast, OSB, David. “The Mystical Core of Organized Religion.” Grateful.org, Grateful Living, grateful.org/resource/dsr-mystical-core-religion/.

7 “Universal Man” appears in the Book of Divine Works. Although Hildegard wrote the detailed descriptions of the visions referenced in this book, illuminators painted the images at a later time. While there is debate as to whether Hildegard created the illustrations in Scivias herself, these images indicate that the illuminator possessed an intimate understanding of Hildegard’s visions.

8 Allen, Sister Prudence, RSM, “Saint Hildegard of Bingen and the relationship between man and woman.” Excerpt from The Concept of Woman – vol.1: The Aristotelian Revolution 750 BC – AD 1250, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, (1985/1997). http://www.laici.va/content/dam/laici/documenti/donna/teologia/english/Saint%20Hildegard%20of%20Bingen%20and%20the%20relationship%20between%20man%20and%20woman%20.pdf.

9 Singer, Charles, “The Visions of Hildegard of Bingen.” London, England, republished in The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 78 (2005), pp. 57-82, p. 80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2259136/pdf/16197730.pdf.

10 Ibid, 74.

11 Foxhall K. “Making modern migraine medieval: men of science, Hildegard of Bingen and the life of a retrospective diagnosis.” Med Hist. 2014 Jul;58(3):354-74. doi: 10.1017/mdh.2014.28. PMID: 25045179; PMCID: PMC4103393. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4103393/.

12 Book of Divine Works, Matthew Fox, editor, Bear & Company Inc., 1987, p. 8.

13 Ibid, 207.

14 Ibid, xiii.

15 Ibid, xii.

This piece is excerpted from the Summer 2024 issue of Parabola, REALITY. You can find the full issue on our online store.