Several generations of conservatives were awed by William F. Buckley; they revered him.

For starters, he was the origin point of conservatism in many conservatives’ accounts. Writer George F. Will said he was the movement’s personal book of “Genesis.” A former National Review editor called him the “Michael Jordan of language.” An observer framed the growth of conservatism on college campuses in the 1960s this way: “A flock of little Buckleys now torment social scientists in colleges large and small.” As I argue in “Creating Conservatism,” Buckley was conservatives’ sun, moon and stars, their pioneer, priest, poet, provocateur, philosopher, publisher and public relations professional.

But as powerful as Buckley was among American conservatives, he can feel removed from today’s conservatism.

Though he died in 2008, Buckley’s twilight began well before that. He left National Review in 2004, and “Firing Line” aired his last debate in 1999. Politicians like Donald Trump or pundits like Ben Shapiro or Tucker Carlson, all famously contentious, are more salient for present-day conservatives. Buckley’s politics are also distant from contemporary conservatism. His death preceded Trump’s political rise, but Buckley called him a self-enchanted “demagogue” in 2000. It is also difficult to imagine that Buckley, the fervent Cold Warrior whose first two books, “God and Man at Yale” and “McCarthy and His Enemies,” warned about communism coming home would have many nice things to say about Putin’s Russia.

So, which account is correct for Trump-era conservatives, Buckley the god-like figure or the forgotten founder? Additionally, would Buckley recognize the movement that he, in no small way, started and sustained? In answering these questions, I emphasize one of the many roles Buckley played for conservatives over the others: the gleeful gladiator.

Buckley’s influence among conservatives may have waned in some ways but, when it comes to ideological combat, his impact is widespread. Buckley obsessed over what he called “the conservative demonstration” in “Up From Liberalism.” Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, Buckley’s new conservative movement was taking on big targets: both political parties, the Soviet Union, elite universities, Hollywood and more. He may have had a patrician persona, but Buckley and early conservatives wrote as outsiders, as party-crashers. As Buckley argued, “Conservatives, as a minority, must learn to agonize more meticulously.” As such, Buckley wanted conservatives to stand out by making creative rhetorical choices, and he modeled a grandstanding style for them.

Buckley taught conservatives to fight like gladiators.

His gladiatorial style was guided by one mantra: don’t bore. Consistent with the bravado of the Russell Crowe-stereotype of ancient gladiators or the dramatic struts and flexes of the typical modern professional wrestler, Buckley’s style aimed to dazzle, to enchant. He crafted a “conservative demonstration” that called attention to itself the way a firework does.

Although he was an adept insulter, Buckley was not modelling simple meanness. He hoped to interrupt dry political arguments and give upstart post-World War II conservatives some argumentative credibility. Several rhetorical strategies were useful in that quest. First and most famously, Buckley used big words and lots of them. His writing was, to use a word he liked, sesquipedalian. He was, one conservative said, the “prince of polysyllabism, a “hapax legomenon.” In the first issue of National Review in 1955, he wrote that conservative meant attacking the status quo, standing “athwart history.” He got so much attention for such pretension that he even wrote several essays on language, and his editor even compiled a 100-page “Buckley Lexicon” consisting of odd words like “dreadnought,” “dithyrambic,” “oleaginous,” “tergiversation,” and “voluptuarian.” (Not to be outdone, Buckley published his own lexicon as well.) Buckley, playing the preening warrior who winks at the crowd while holding a strange weapon, once told Morley Safer, “There is nothing more amusing than theatrical pomposity.”

Although he was an adept insulter, Buckley was not modelling simple meanness. He hoped to interrupt dry political arguments and give upstart post-World War II conservatives some argumentative credibility. Several rhetorical strategies were useful in that quest. First and most famously, Buckley used big words and lots of them. His writing was, to use a word he liked, sesquipedalian. He was, one conservative said, the “prince of polysyllabism, a “hapax legomenon.” In the first issue of National Review in 1955, he wrote that conservative meant attacking the status quo, standing “athwart history.” He got so much attention for such pretension that he even wrote several essays on language, and his editor even compiled a 100-page “Buckley Lexicon” consisting of odd words like “dreadnought,” “dithyrambic,” “oleaginous,” “tergiversation,” and “voluptuarian.” (Not to be outdone, Buckley published his own lexicon as well.) Buckley, playing the preening warrior who winks at the crowd while holding a strange weapon, once told Morley Safer, “There is nothing more amusing than theatrical pomposity.”

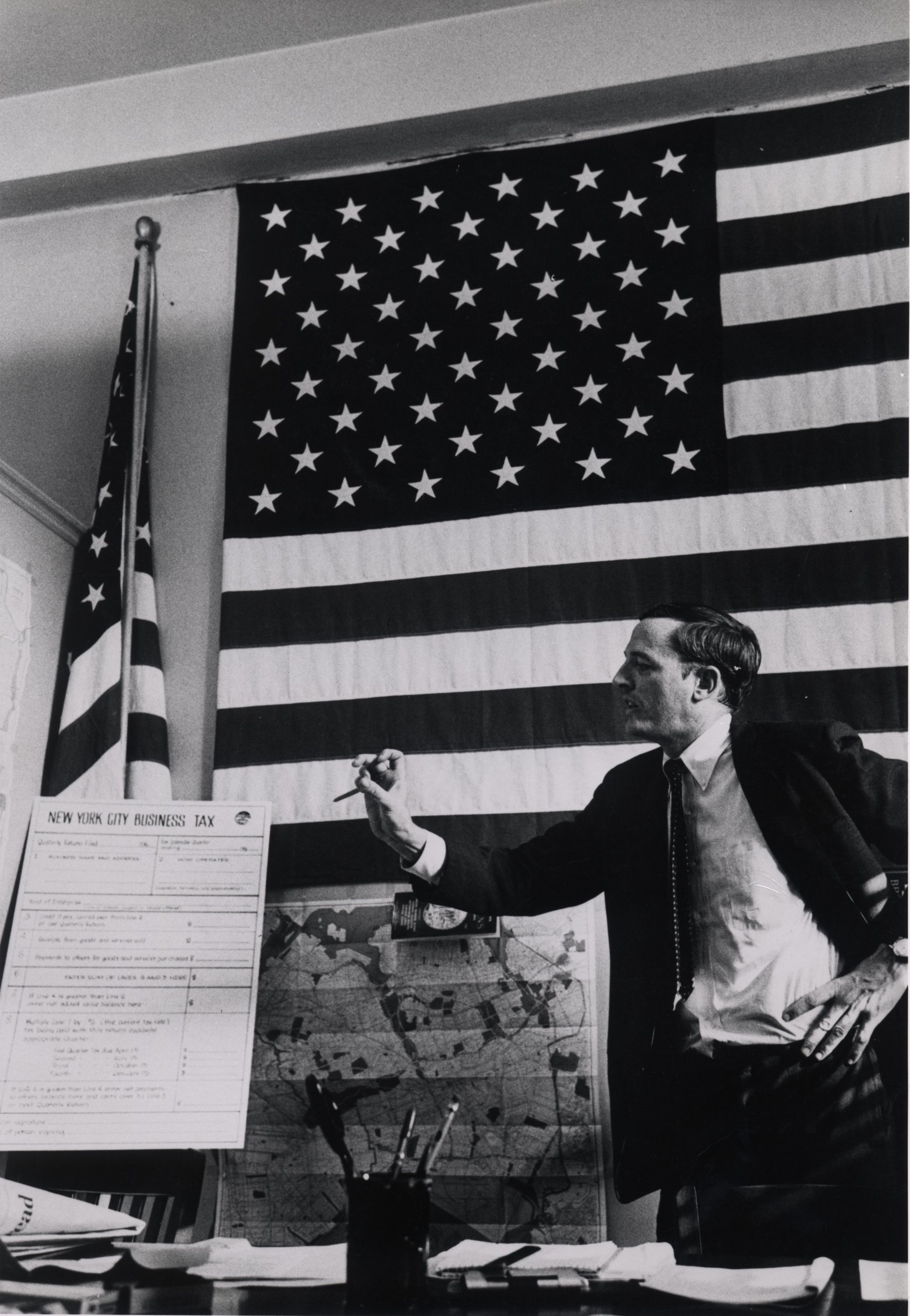

William F. Buckley and Blank Panther Leader Eldridge Cleaver on “Firing Line,” courtesy of the Hoover Institution.

Buckley’s rhetorical arsenal included far more than stylistic swagger like big words and long sentences. In his many books and columns, on “Firing Line” and during public speeches, Buckley wrote and spoke many short, snappy sentences as well – one of which became the title of a collection of his writings: “Cancel Your Own Goddam Subscription.” Buckley’s language, whether simple or ornate, mobilized conservatives and irritated opponents. So did the variety of his attacks. He could be very sarcastic, as he was in an early National Review piece called “Reflections on the Failure of ‘National Review’ to Live Up to Liberal Expectations.” His posture was consistently ironic and mocking, allowing him to turn power dynamics upside down as he did when he, still in his early 20s, turned his prestigious alma mater into his student in “God and Man at Yale.” His take-downs could also be detailed and policy-oriented. His arguments could be high-minded and philosophical. His approach could be insinuating and accusatory. He could be also be cruel and, as his long-time rival Gore Vidal found out, he could be threatening. All told, Buckley usually debated with both composure and an impish grin. Neither of these qualities was present in the Vidal affair, a fact Buckley regretted for decades.

Conservatives took note of their fighting founder’s argumentative acumen. Buckley “personified the militant conservative ‘movement,’” Pat Buchanan wrote when he ran for president in 1988, “and we were the mujahadeen.” One conservative thought of Buckley as “Braveheart lopping off the heads of one faculty lord and knight after another.” Another characterized him as “Henry at Agincourt, instructing and inspiring through noble speech and leading by courageous example.” Rush Limbaugh even tried to “talk,” “dress,” “write” and “think like him.” He remembered: “I was reading Buckley when I was 15, 16 years old, and I said, ‘Boy, I wish I could be that . . . How does he know all these words?’ I’d sit there with the dictionary looking up words that he used, and points that he made.”

Of the many celebrations of Buckley’s prowess, however, one tale stands out. In 1985, Ronald Reagan told an epic story of Buckley on the battlefield of ideas. Reagan recalled a Cold War period “when nightmare and danger reigned.” Conservatives lacked a “champion in the critical battle of style and content,” and Buckley filled the void. Buckley, Reagan said, was our “Galahad,” ready to cross swords with any challenger “in the critical battle of point and counterpoint.”

As the media scholar Heather Hendershot has shown in her book “Open to Debate,” what set Buckley’s “Firing Line” apart was the sheer variety of guests Buckley sparred with. Buckley had an “any topic, any guest” attitude. This take-all-comers approach didn’t always serve him well, on or off the show. For example, Buckley was bested by James Baldwin in a 1965 debate at Cambridge. On the whole, however, Buckley taught conservatives how to fight, and, interestingly, he also trained conservatives to fight one another over the meaning of conservatism. Put differently, he encouraged conservatives to welcome debates, even with each other. Buckley wanted attention-grabbing gladiators, but he didn’t demand loyal ones.

Promoting conflict among conservatives was, in fact, a key part of Buckley’s philosophy.

When he founded National Review in 1955, he wrote that he envisioned a political magazine with “intelligence” and “no crackpottery.” Buckley would not publish just anything for the sake of being provocative. He cordoned off writers who voiced the conspiratorial views of antisemites or the John Birch Society. National Review did not support civil rights reforms, but it did consistently decry racism and instruct conservatives to find non-racist reasons to support their positions.

Beyond these few soft boundaries, Buckley wished for a magazine that was alive and energetic, one electric with rival conservative points of view: “But I want some positively unsettling vigor, a sense of abandon, and joy, and cocksureness that may, indeed, be interpreted by some as indiscretion.” National Review would not be a house organ; there would be no house style, no party line.

Buckley scorned “house theologians” and supported “a little creative heresy as good for the system.” He then guaranteed internal squabbles by running articles in National Review by a bevy Right-leaning groups who were gathering under this new “conservative” tent after World War II. The magazine featured libertarians, traditionalists, theocrats, neo-medievalists, former Communists, segregationists, integrationists, semi-anarchists, and semi-monarchists. By his design, Buckley’s more-the-merrier conservatism was at war with itself; it had what the historian Kim Phillips-Fein called a “baroque strangeness.” It was no surprise then that “What is conservatism?” was the question Buckley heard most frequently from lecture audiences. Buckley delighted in deadpanning an impenetrable answer: “the paradigm of essences towards which the phenomenology of the world is in continuing approximation.” In moments when a tidy summary of conservatism was called for, Buckley ribbed his audience by providing the opposite. He used the question as an opportunity to entertain them by violating their expectations. He left them wanting, but not necessarily knowing, more.

Buckley was combative, even about conservatism, and he helped conservatives adopt similar poses for more than 50 years. His conservative style was great for provocation, not deliberation, more contentious than cohesive. A conservatism that remains daring and surprising, a “conservative demonstration” that commands headlines and compels clicks, a conservatism that sub-divides into warring camps continues to follow Buckley’s lead. However, if conservatives prefer orthodoxy or pay homage to a singular authority from whom no true conservative can deviate, they stray from Buckley’s legacy. If they sequester themselves or their audiences from dialogue, if they prefer discussions with like-minded insiders over debates with opponents, they risk pushing Buckley further into conservatism’s past. A conservatism that engages in what he labeled “crackpottery,” indulges far-fetched conspiracy theories or lines up behind bigots, veers from paths first broken by Buckley.