Greasy, backbeat swampy, funky stuff: The brilliance that was Jerry Reed

Going on the record for the first time, bassist John Harris removes the rose-colored glasses in recollecting his 1988–1989 onstage tenure with certified fretboard wizard Jerry Reed exclusively below. When not tearing up the charts with crossover hits “Amos Moses” and “When You’re Hot, You’re Hot,” the posthumous Country Music Hall of Famer comically pulled his own weight alongside movie stars Burt Reynolds [Smokey and the Bandit], Gene Hackman [Bat*21], Robin Williams [The Survivors], and as the “What’s a matter with you boy!” Coach Red Beaulieu to Adam Sandler’s The Waterboy. Another Reed milestone — his Smokey theme song “East Bound and Down” can be heard in a Super Bowl commercial pushing F-150 trucks.

The John Harris Interview

What was one of the first instances where you distinctly remember hearing Jerry Reed?

In 1973 or 1974 I was driving around Albuquerque a few years before I moved to Nashville and “Amos Moses” [No. 8 POP, No. 16 C&W, October 1970] came on the radio. I thought, ‘I’d love to play with that guy.’

I wasn’t a country music fan at that time, but the format for the station I tuned into was country. Reed’s stuff was greasy, backbeat swampy, funky stuff, and it turned my head around. I don’t remember what I ate for breakfast this morning, but that is a clear memory even that long ago.

Employed with Reed from January 1988 to circa March 1989, did you audition with Exile piano player Marlon Hargis?

Yeah, we auditioned at the same time exactly. I met Ric McClure [drummer and band leader for Reed from 1981–1989] at a jam one night, and he got me the audition for Reed. I listened to everything I could get my hands on, which was a little tougher back then.

It was a very informal audition with Ric, Marlon, and Reed. We jammed on some 1–4–5 chord changes, did one or two Reed tunes, and it was over. I think they told me I had the job that day.

What stands out when you recall your very first concert with Reed?

My first show’s main emotion was joy that I didn’t screw anything up. I’m drawing a blank on where it took place.

Did Reed have any superstitions or rituals before a show?

Not to my knowledge, unless you count the chicken sacrifice before every gig. I’m kidding.

What was Reed like personality wise?

I really liked Reed. As a Vietnam veteran, he showed a certain respect towards me [Reed was assigned to the Army’s Circle A Wranglers band during the 1959–1961 Cold War era and was honorably discharged as a Specialist 4]. I prefer not to talk about my experiences in Vietnam.

But he had a habit of promising the band a slot on whatever he was recording, that rarely, if ever happened. That was mostly what I heard from the guys that had been with him for awhile. Reed was very focused on his film career, and I always had the feeling that he would drop the music in a heartbeat.

Most of the time he would leave before the chaser, a tune that you bring the artist on and off the stage with, was over, leaving a lot of his fans disappointed. In Reed’s case the chaser was almost always “East Bound and Down.” Having his own bus, he could boogie on his way to the next gig.

We also only played about 7 or 8 songs during each show because he loved to talk. So my chops kinda went south. Actually the band would do some numbers by ourselves before Reed went onstage. There was a tune by the Dixie Dregs [an Augusta, Georgia-based instrumental jazz-rock quintet] that we did that was challenging.

Did you catch any musicians watching Reed perform?

Since I was with Reed during a period where he told more stories than he played songs, we had some musicians walk out including Toy Caldwell [the Marshall Tucker Band’s chief guitarist-songwriter who can be heard belting out the Southern Rock anthem “Can’t You See”].

Toy and a few of his band mates / crew came to hear Reed play, but he was handing off most of the solos to Kenny Penny [the longest-tenured band member going back to 1974] and Bobby Lovett. Both fine players, but Toy wanted Reed. They made a fairly big deal out of leaving.

I can’t think of a more rhymin’ name than Kenny Penny.

Kenny was probably the most talented fellow in the band — mandolin, fiddle, guitar, bass, engineer — and an all-around good guy. He has insights and stories that would be very entertaining. He is Texas born and still lives there.

Since you rightly consider Reed’s music to be “greasy, backbeat swampy, funky stuff,” did you play to predominantly country audiences? And did the Guitar Man consider himself to be a country artist?

Reed’s appeal was broader than most country artists. It seemed like a lot of musicians showed up for the gigs, but when we played places like Branson or state fairs, it was basically a pure country audience.

I don’t think Reed considered himself to be a “country artist” since he identified with rock and roll to an extent vis-à-vis Elvis, and he was a fan of Big Joe Turner and other non-country acts. We did a Big Joe tune called “Lipstick, Powder and Paint” [No. 8 R&B, July 1956] onstage and at least one more occasionally.

Clarence Carter’s “Patches” [a No. 30 C&W A-side for Reed in September 1981 from The Man with the Golden Thumb] seemed to be one of his favorites, although we only performed the Muscle Shoals staple a couple of times.

What was one of the worst gigs that you ever played with Reed?

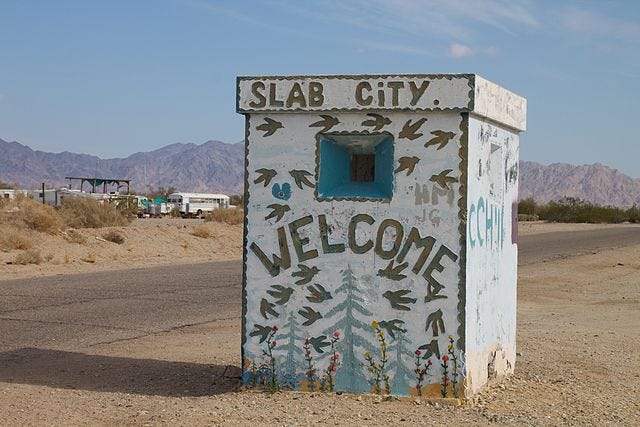

I didn’t really have any “bad” gigs, but a priceless story comes to mind. Before I joined, the band and Reed were booked at a venue in Canada called the Hunt Club. Somehow Reed got it in his mind that it was a place to shoot some skeet and maybe a little hunting on the side. Well, the Hunt Club was a truck stop topless dance place. Word has it that Reed shed a few tears when realization set in.

There was one festival we played where I was on Reed’s bus. The promoter, who was losing his shirt, got on the bus and tearfully asked Jerry to lower his price. I can’t remember the outcome.

Was Reed the kinda guy who read show reviews?

I would seriously doubt if he ever read one. There was a story about meeting with RCA executives at one of his shows in Los Angeles. Reed was told they wanted to talk to him so he sent Ric, who then had a bad stutter, in his stead. Pretty humorous.

Did Reed open up for any artists?

We opened up for the Judds in Nashville once. That was a great gig. The mom side of it was great — Naomi said hello to everybody in our band. The daughter — Wynonna — not so much. We played a couple of festivals where lots of acts were slated, but the Judds was a one-off situation.

Did you have any one-on-one moments with Reed?

One thing I used to look forward to was Reed calling me over to his bus to provide bass back-up for practicing his solos. I once played “Summertime” [a jazz standard composed by George Gershwin for the 1935 opera Porgy and Bess; Reed and Chet Atkins opened their 1992 collaborative album Sneakin’ Around with it] for four hours. No improvisation was allowed on the bass though.

This was one of Reed’s comments verbatim — when I got a little spacey after the second hour of “Summertime,” I started walking the bass part and adding a little modal spice to my part. He quit playing and said, “Hey cock, you think that is a guitar? Just play the changes.” It kinda stung, but it wasn’t about me.

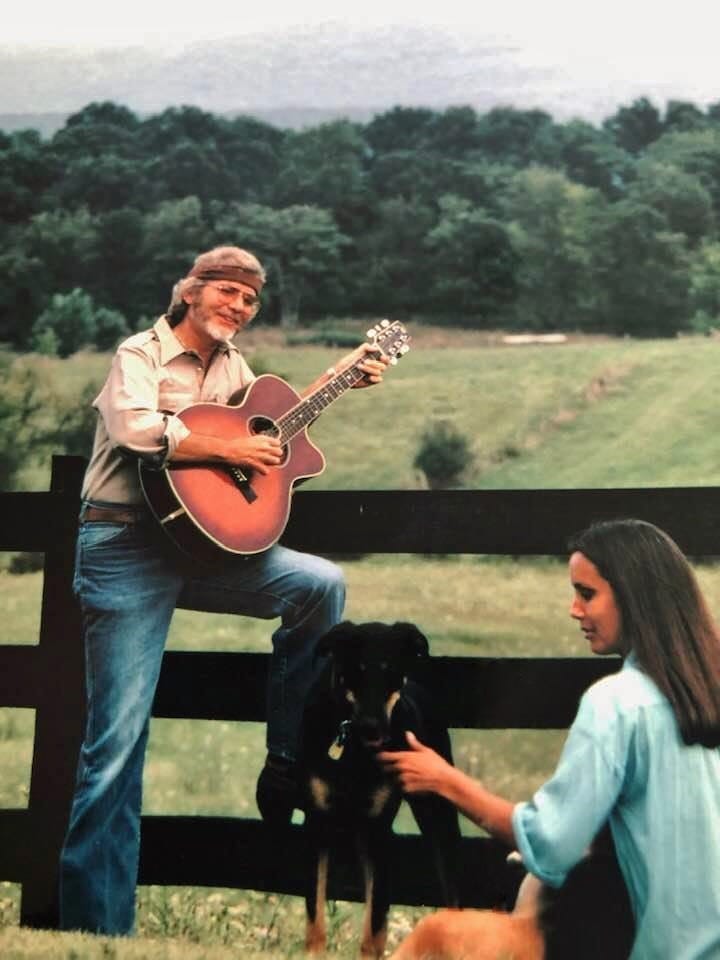

I really heard some virtuoso stuff on his bus. Reed would play this beautiful nylon string acoustic guitar most of the time and switch to a Telecaster at shows. As far as I remember, the nylon string never left the bus. If he ever played anything but the Telly at shows, I don’t recall it. The kinda strange thing was, he would play that nylon string constantly while he was alone. It had a very broad string spacing as opposed to the Telly, which is really skinny.

I wish I had brought a tape recorder with me during those occasions. I don’t think it would have been okay with Reed, so I never did.

Imagine the artistic comeback a producer like Rick Rubin could have coaxed out of Reed in a stripped down setting. Reed’s late ’60s and early ’70s RCA Victor albums can sometimes be a slog with all the countrypolitan sweetening — e.g. backing female choruses and string overdubs overseen by Chet Atkins.

It was the bane of that era. The first session I did in L.A. in the early ’70s was with a one-hit wonder named Chi Coltrane [although Harris was not on it, the singer-keyboardist’s “Thunder and Lightning” reached No. 17 POP in June 1972]. It was cool — Hal Blaine was on drums — until the producer said those very words, “Let’s sweeten it up with some strings.” He cheesed it completely.

Some of the stuff Reed played on the bus was pure genius. Reed’s style changed to fit that nylon string guitar — more fingers, less pick. Reed would have killed it collaborating with Rubin or any producer who encouraged him in such an intimate setting.

Why did you leave Reed’s band?

We played in Dallas, and Ric told me that the band was being let go. After the gig Reed took us to Ruth’s Chris Steak House where I ate everything I could. The last time I saw or spoke with Reed, I had a face full of very expensive filet mignon — I ordered two — and a good bottle of Merlot that I put on his tab. I wasn’t really pissed, and I accepted the fact that Reed had a singular mind and was off to new things.

I don’t know if everyone was let go when I was. I know Reed went out again for awhile with bassist Roy Vogt [Hargis must have left at the same time, as he confirms that he never played with Vogt. McClure also departed at some point in 1989. It is uncertain when Penny resigned. If Lovett temporarily left, it was not for long as he was in Reed’s band until the end of the road arrived quietly in November 2004]. But we were fired, no matter how you put it. It was Reed’s choice.

Right after that I was grateful for Kenny getting me a job with Johnny Russell [the composer behind Buck Owens’ “Act Naturally” and George Strait’s “Let’s Fall to Pieces Together”]. I haven’t seen the guys in ages, but a couple of years ago I friended Marlon and Kenny on Facebook but don’t really keep in touch. Being with Reed is still one of my favorite career moments.

Did you make any TV appearances while you were with Reed?

Not to my knowledge, and I sure wish there were videos or photos of us together. Maybe somebody reading this will prove me wrong.

What other artists are on your résumé?

As a youngster in Clovis, New Mexico, I was signed to the Norman Petty Agency and played trumpet on the Fireballs’ Bottle of Wine album [1968].

Nashville was a tight little community back then. I was incredibly lucky there, probably not a great bassist but always on time and prepared. My first artist date was a 4 a.m. call from bassist Larry Paxton’s brother for three sub-gigs with Ray Price. After that things got easier.

My résumé consists of Connie Smith, Margo Smith, Johnny Russell, David Lee Murphy, Danielle Alexander, and tons of demos with Warren Haynes [e.g. Gov’t Mule, Allman Brothers Band], incidentally a hell of a nice guy. I briefly joined Delbert McClinton’s band in 1990.

Next I moved to Norway for a gig with Arne Benoni that lasted a few months. I was about 300 miles above the Arctic Circle in a Volvo tour bus when I got my first cell phone call ever —the lady in question was Sandra Wright — asking me to come back to Nashville and play with her. It hit about 45 degrees below zero that night and actually froze our oil. I was on a plane in a matter of hours [Author’s Note: Raised in Memphis, the soul-stirring R&B diva was spotted by Stax Records president Jim Stewart in 1974 and could have been a competing chart presence if the label had been able to actively promote her. Instead, Stax entered involuntary bankruptcy by the subsequent year].

We played in Nashville for about a year until we moved as a band to Vermont to be closer to the New York City-based Hipshake record label, who secured us a deal for the Shake You Down album [1995]. It featured Warren Haynes on guitar, Joseph “Joe” Wooten [keyboards; Vic’s brother], Sammy Figueroa on congas, and production by Jay Newland, who received four Grammys for Norah Jones’ Come Away with Me debut [2002].

Although Shake You Down didn’t do all that well — Sandra was black and overweight so we never got the push we needed — she is still the best singer I ever played with. Everyone that plays music would be jealous of my joy of the nearly 20 years we played together. Sandra never once lost her voice or passion even as the schedule waned because of her illness. She had to be airlifted to the hospital and died in flight from a blood clot at age 61. I am sure Reed would have adored her. RIP Sandra [October 1, 1948 — January 10, 2010].

What bass guitar did you play with Reed?

I used an XL2 Steinberger four-string bass built in the mid-’80s that Reed offered to burn once. It sounded good but looked weird — there were no tuning keys on the end and basically resembled a stick-like slab of black carbon graphite. Here’s a photo of a near-identical Steinberger, except mine had a foldable knee rest on the bottom so it must have been an ’85 or ’86 model.

When I quit Johnny Russell’s band to join Delbert McClinton about a year after Reed, our first gig was in London. I had no adequate luggage so I hocked the Steinberger and gave my girl the ticket. It was gone when I returned. I never heard of Reed being able to accompany himself on bass, but I am sure he could have. One of those savant types.

These days I just have an F-Bass made by George Furlanetto in Canada. It’s a BN-6 custom model with a spalted maple top delivered to me in 2003. It’s still the best bass I’ve ever played. I teach bass to a few select students here in Albuquerque and play out occasionally. I’m getting too old and cranky to tour.

What is your takeaway from working with the “Ko-Ko Joe” swamp rocker?

What I found best about the gig were surely the times when I’d get a call from Reed saying, “Go get a twin [a Fender Twin Reverb standard amp] out of the bus, cock, and bring your bass to my room [or bus].” What usually followed were two or three hours of playing changes for him to solo over. That’s when I heard the brilliance that was Jerry Reed.

© Jeremy Roberts, 2019. All rights reserved. To touch base, email jeremylr@windstream.net and mention which story led you my way. I appreciate it sincerely.