Memento Mori, Memento Vivere

Use an exercise about death to help you live a better life.

A couple of days ago, I was sent a new book to review, a daily diary that’s designed to help people live a more self-aware and values-aligned life. Flicking through its pages, I spotted that the authors, both of them psychologists like me, had included a variety of values-clarification and values-tracking exercises throughout. That’s incredibly helpful, because it can be challenging to summarise our core values — it’s not something that we’re asked to do very often.

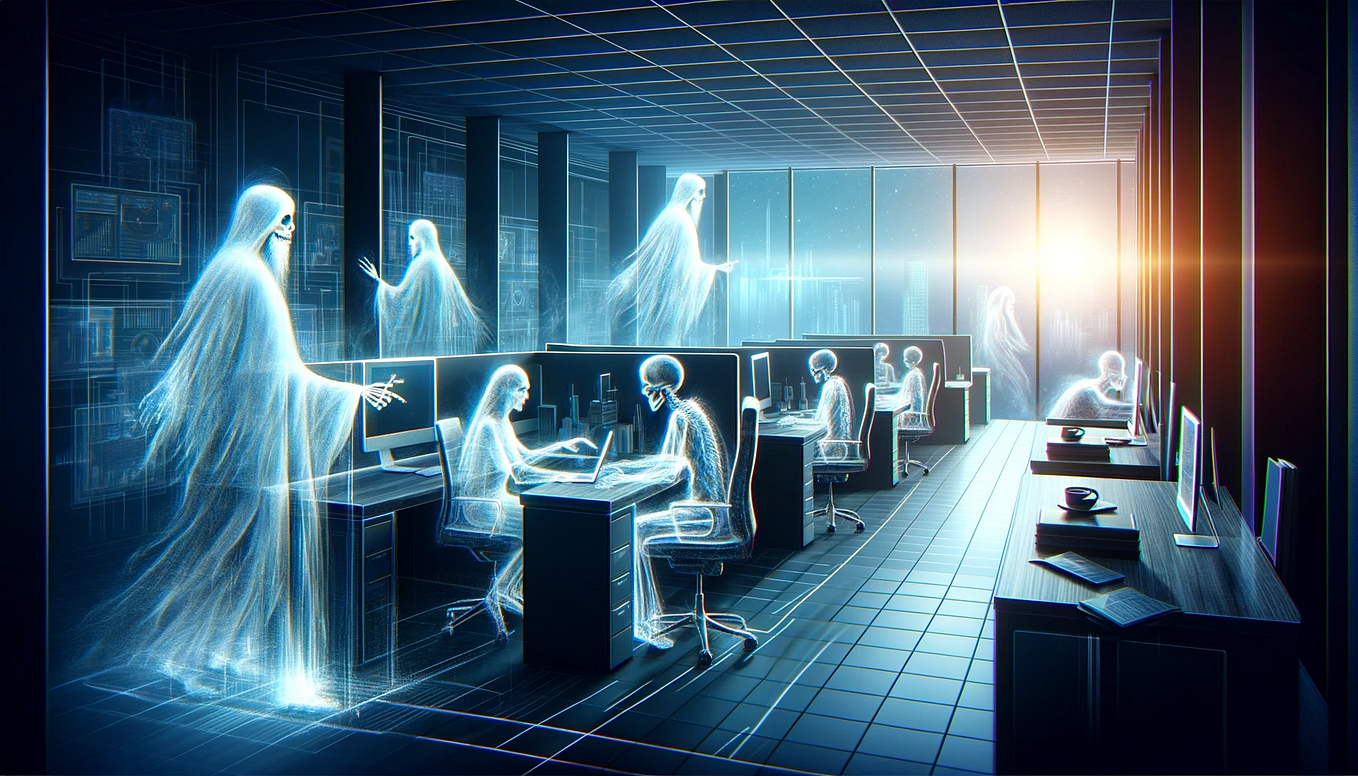

But modern life has made awareness of our values even tougher. We know how we’re supposed to appear. We know which of our behaviours people respond to positively, which they punish and which they reward. We know what kind of photos and posts will get the likes and the retweets.

We know all those things. But we often don’t know (or can’t easily contact) what we actually, genuinely care about. Our ability to articulate our values has severely atrophied in these performative, distracting, hectic times. Deprived of the inner bandwidth to connect with what we value, we drop back into mindlessly performing for other people. We confuse true values with societally imposed goals.

About halfway through this diary, I encountered one of my favourite values clarification exercises. Predictably, it was prefaced with an apology. I don’t know that I’ve ever seen anyone conduct this type of exercise without simultaneously saying sorry.

Sorry if this seems rather morbid, the first sentence said, or something to that effect. I know it seems kind of weird to write your own eulogy.

I’ve been guilty of this cautious, deferential disclaiming about this exercise in the past, but my clinical supervisor bashed it out of me. In his own work, he has no qualms about quickly sketching the shape of a gravestone on a spare bit of paper and handing it over to a client. What would it say on this gravestone if you died tomorrow? he’ll say. No punches pulled there. I have to presume that he contextualises it somewhat more than that, so let me contextualise it for you.

Yes, my entire wardrobe is black, and I write about death. But these proclivities are not the main reasons that the eulogy exercise — also known as the obituary exercise — is one of my go-to activities for psychotherapy clients and workshop attendees. If you have ever lost anyone close to you, if you have ever come close to death yourself, you may have noticed the values-clarifying effect that this experience that this can have.

In short, staring the reality of your mortality in the face is a fast track to clarifying how you want to live.

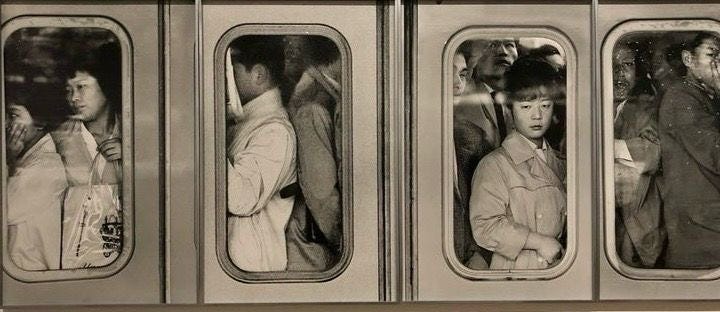

For many centuries, artists and craftspeople of all stripes — jewellers and sculptors, painters and craftspeople — wove memento mori into their creations. You’ve seen them: the skull and crossbones on a crumbling centuries-old tombstone; the cadaverous body carved in stone, reclining on a grave marker; the skeleton dancing with a young woman in a Flemish painting. Memento mori were intended to remind people that they too must die, but they weren’t merely scaremongering. Memento mori were intended to simultaneously serve as memento vivere — reminders to live, and to live as well as you can.

Memento mori are still around, but the industrial and the digital ages have diluted their impact. Many of us have never seen an actual dead body. Our digital devices have rendered death closer and further away at the same time, pushing it through the sanitising, distancing filters of binary code and our connected devices. Skulls are present everywhere in popular culture, so much so that they rarely serve as an actual reminder of our transience. They are scattered over the scarf I am wearing right now, and I seriously doubt that my neckwear will, on its own, launch anyone I meet today into a contemplation of their mortality and how they want to live.

Start counting them now. From the time you read this post until the end of the day, how much skull iconography can you spot? Will any of these flesh-stripped grinning faces make you think about the fact that you will die? Will any of them prompt a reflection on whether you are living the life you want? These days, it takes a bit more than that.

If the idea of writing your own eulogy gives you serious pause, maybe it’s all the more reason to do it. Perhaps it’s a sign that you’re already too far removed from the awareness of your own eventual end for you to be able to use that awareness to live a fuller life.

Some people prefer the tombstone exercise, keeping it short and sweet so as not to exhaust the monumental mason who’s carving your grave marker. The basic tombstone exercise goes like this:

- If you were knocked down by a bus tomorrow, what three adjectives would go on your tombstone, three words that would capture you and your life as they are now?

- If for the next forty years you lived a life full of qualities that you valued, being the person you wanted to be, what three adjectives would appear on your tombstone then?

- Is there a difference?

- What stands in the way of you moving towards the values and characteristics that would appear on tombstone #2?

This exercise has the advantage of helping you create a handful of values that are easily recalled, a set of touchstones to quickly check your moment-to-moment decisions against.

But there are tombstones and tombstones, and being a wordy sort of person, my favourite template for the eulogy exercise is the grave of Lidian Emerson, the wife of American essayist and poet Ralph Emerson. Doing a eulogy like this is a deeper reflective exercise. Lidian died in 1892, after a life clearly lived in line with what she cared about, and her final resting place is Poet’s Corner in the beautiful, bucolic Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord Massachusetts. The eulogy that appears on it is so long that it continues on the overleaf.

This carved tribute is about 175 words long, and I find it utterly lovely. For years, every time I have read it out loud, my voice has quavered at, ‘She loved her Town.’ This tells me something about my own values. I value community, and deep and lasting connections with trusted others, and my emotion is connected with the fact that these values have often been challenged in my peripatetic life as an expatriate.

Take a couple of minutes to reflect on what else you notice about this eulogy, and your reactions to it. For me, there are a couple of other things that you should keep in mind if you want to do this exercise for yourself.

First, it is absolutely personal, steering clear for the most part of eulogistic cliches and stock phrases. Anyone who reads it can grasp Lidian’s essence and can feel how she was experienced by the people who knew her. She remembered them that were in bonds, as bound with her, it reads, for Lidian was a passionate anti-slavery advocate. She lived the simple and hardy life of old New England. She cared for persons more than books. Lidian’s values emerge from the granite clearly and crisply — I do not know what she looked like, but I can feel her. I can understand her legacy.

Second, this gravemarker expresses who Lidian was not just as an individual, but also who she was in connection with other people, with her community, with the physical and natural world, and with the spiritual. These are the realms of our human existence. These are the realms where values live. In these various zones — personal, interpersonal, physical, spiritual — our values flourish when we are aware of them and honour them, and falter when we forget them or are too afraid to live them.

So face your death anxiety down, do yourself a favour, and try this yourself. Don’t stop short at memento mori. Remembering that you will die, don’t instantly, reflexively turn away from that awareness. Use it. Use the fact that death will come, and use this exercise, as a memento viveri — as a way to remember how to live.

First, write a eulogy that would sum up your life if you died unexpectedly tomorrow. (Engaging with this in your imagination will not make it happen.) The text you write should be an honest snapshot of where and who you feel you are right now in your life.

An example excerpt could be: Here lies Jane Smith. Her life was dominated by her anxieties. She was limited so much by everything that she was afraid of. She never had the courage to find her way out, and she died without having tried. You get the picture. Write it in the third person, as though it were someone else writing about you, and aim for about 150–200 words, like Lidian’s gravemarker. Doing this eulogy may be tough — there may be things in it that upset you, because it can be hard when we realise how far we have drifted from what we care about. Be kind to yourself.

Second, imagine that you die 30, 40, or 50 years from now. This eulogy is beautiful. It describes a life lived the way you want. You were the person you wanted to be. You did the things you wanted, followed your passions, did what you cared about, what moved and impassioned you. It is a life about which you would be proud. Again, use about 150–200 words.

Afterwards, look at the two eulogies side by side. Spend some time just noticing what thoughts, feelings and images come up as you read them. Perhaps talk with someone you care about. Share your thoughts and feelings with them.

What would have to change about your life in order to live the life that was captured in the second eulogy? What has been standing in the way?

What is it worth to you to have a life like that?

Perhaps it’s worth making the change you have been reluctant to make. Perhaps it’s worth confronting the anxieties that have been holding you back, worth taking a big breath and and pushing past your internal and external barriers. Maybe it’s worth making a move — small, medium, bold — in the direction you want to go. Right now.

Because someday, you shall die. Do not go gently into that good night, Dylan Thomas wrote, speaking about the end of life. Rage, rage against the dying of the light. But however far you may be from death, if you are not living a life that you value, the light is already dying. Do not wait until the end to rage, to rave, to blaze.

Memento mori. Memento vivere.