Editor's note: The following interview contains mild spoilers.

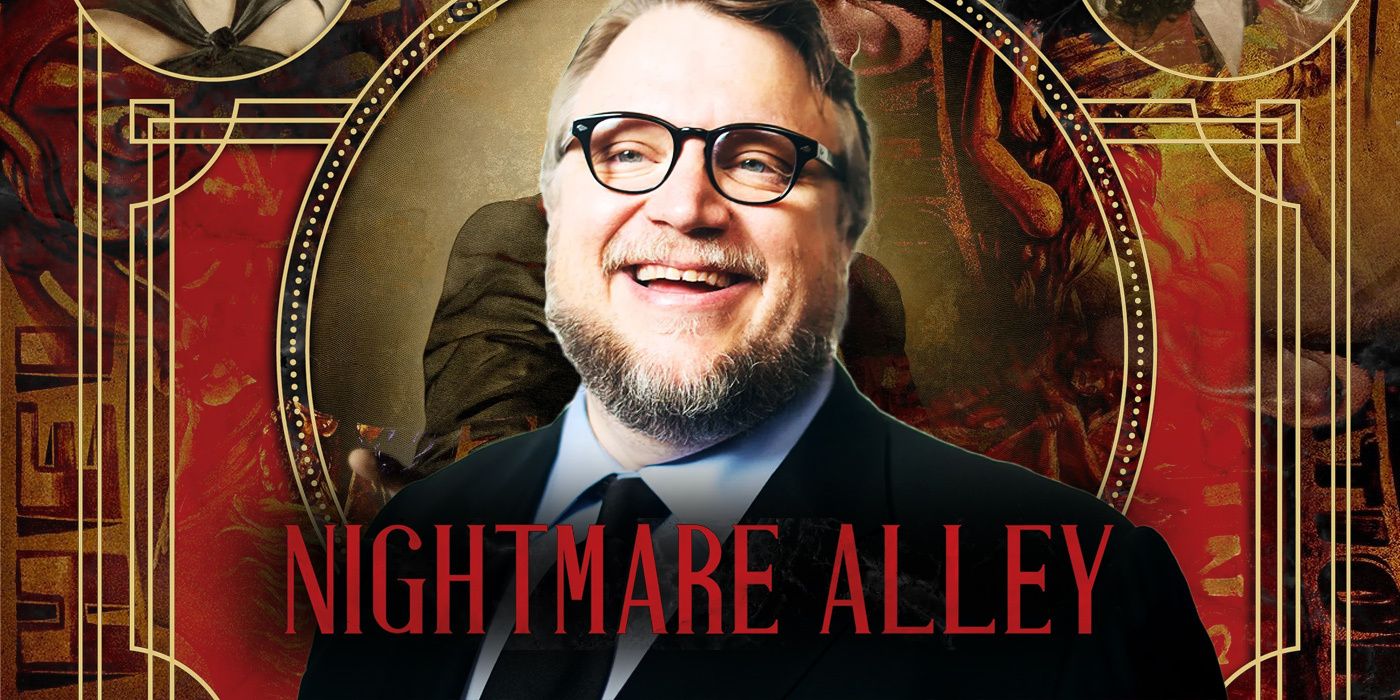

If you’re a fan of Guillermo del Toro and enjoy hearing him talk about movies, I’m about to make you very happy. Shortly before Nightmare Alley was released, I landed an extended and wide-ranging interview with the brilliant filmmaker. During the almost fifty-minute conversation, del Toro broke down the making of Nightmare Alley and shared numerous stories I hadn’t heard anywhere else. This included what was in his 3-hour 19-minute version of the film (the final version is an hour shorter), how he personally bought some of the props and set dressing on eBay and what they did to make sure everything was period-specific, what exactly changed as a result of the long COVID shutdown, why he wants people to see the black and white version, the happy ending in the middle of the film and the way they shot it to emphasize the moment, why they tried to light Bradley Cooper with the other characters in the movie, his personal film noir inspirations, and so much more I can’t list it all here.

If you’re not familiar with Nightmare Alley, the film was adapted by del Toro and Kim Morgan from William Lindsay Gresham’s 1946 novel of the same name. The novel was previously made into a film in 1947 with Tyrone Power, but wasn’t as faithful to the source material. Del Toro’s version stars Cooper as Stanton “Stan” Carlisle, an ambitious con man who learned his craft working at a seedy traveling carnival. As he gets more successful, he teams up with Dr. Lilith Ritter (Cate Blanchett), who may be more dangerous than he is. The rest of the all-star cast includes Rooney Mara, Toni Collette, Willem Dafoe, Richard Jenkins, Ron Perlman, David Strathairn, Clifton Collins Jr., Tim Blake Nelson, and Mary Steenburgen.

Since many of you enjoy reading interviews, while others want to watch video, you can either watch Del Toro in the player above or read the full transcript below. Nightmare Alley is now playing in theaters and I strongly recommend checking it out while it’s playing on a movie screen.

COLLIDER: If someone has actually never seen, and I don't know who these people are, but if someone has never seen anything that you've done what is the first thing you'd like them to watch, and why?

GUILLERMO DEL TORO: Of the whole filmography?

Of everything.

DEL TORO: I would say that, either Shape of Water or Pan's Labyrinth would be great primers of what I do. But now, Nightmare, if they could watch two I would say, Pan's and Devil's Backbone or Shape of Water and Nightmare Alley. Those are sort of the alpha and the omega, of what I do.

Everyone knows you have a very nice collection of interesting things in your house. What are some of the newest things you've added to your collection that you might want to tell us about?

DEL TORO: Well, like yesterday for the first time in many months, I had an afternoon free and I needed to distract myself. I painted a model. It was a model of, I don't know if you're familiar with Moebius. Moebius is a comic book, Arzach?

I haven't read that.

DEL TORO: Arzach, there was a beautiful model done by Paul Harding, and he posted it on Twitter. And I said, "Would you please print me a copy of that?" And he sent me a 3D printing, and yesterday I was just all day, painting the model. And now it's on a shelf. Fully painted.

Please post a picture if you can.

DEL TORO: I'll post one on Twitter, I guess.

Yes, please.

DEL TORO: It's not finished. I do one pass in one day, because I'm very impatient. Then I go back and stipple and dry brush, and do more flourishes and stuff like that.

I think people will forgive you if it's not perfect.

DEL TORO: Yeah. I hope they do.

Of all the films you've made, and you think back on them, what do you think ended up being the toughest shot to pull off and why?

DEL TORO: You know, the two, the worst experience was Mimic. The worst. The most difficult have been Pan's and Nightmare Alley. Nightmare was, it was so, such a monster because... I'm being completely candid, here. I thought, "This is a great screenplay, but it is technically not very complicated. We're going to design it and then let the actors play within the frame. And it's going to demand my attention, but it's going to be a fun shoot." This is how I went in.

And then, the movie turned out to be like riding a bull, in every sense. The movie kept asking, every day it kept asking new questions of me, demanding complete answers in a way that no other material did, because it was tonally, a really difficult movie. It was really the language I was trying, with the camera, the language I was trying with the reality of it all, was very different for me. And it was an incredibly wild ride.

Then, complicated by every complication you would expect, whether stopping for COVID, restarting with COVID protocols. Making that movie fit on a budget, with the spectacle I thought it needed, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. You can add all the et ceteras you want. Then, we ended up with a movie that was three hours and twenty minutes and had to compress it and distill it into two hours and nineteen minutes.

I have so many follow ups to that. Because I love talking about the editing process, but I'll get to it in a few minutes. What are you most excited for people to see about Nightmare Alley, and your take on this material?

DEL TORO: The first thing is, the closest I've count tonally to this movie is Devil's Backbone, which was 80% realistic and realism, and 10, 15% fantastical elements. This is all realism, in the sense that it is a stylish movie, it is elegant, it is beautiful. It has the craftsmanship, but it's not supported by fantastical underpinning. There's no creatures, no ghosts, no fantastical elements. I think that is the thing that I'm addressing, and this is reality.

I think it's a movie, not about the past, but about today in every possible way. The notions, the themes, the anguish, the anxiety that the movie has is, of today. And that is the thing I tried to do because noir, noir is the one of the two genres that more clearly reflects the time it was made of, made under. Horror is the other one. Horror and sci fi, fantasy. You have the pulse of the Cold War in the noirs, and the pulse of the Cold War in the movies made at that time. Then you have the post-Vietnam horror and the post-Vietnam noirs, and then you have the '80s, neo-noirs. And each of those eras is reflected in this genre. I wanted to do a movie that was set in the past, but spoke about today.

Obviously, you were heavily influenced by film noirs, making this movie. Can you talk about some of your top film noir inspirations for Nightmare Alley?

DEL TORO: Well, visually I tried to move away from it. I tried to visually make it a movie that happened in the real world, and not stylize it completely. We did follow up the chiaroscuro light of it all, but tried to avoid any of the cliches like voice over, slow turning fans, Venetian blinds, a wet street walked by a detective in an overcoat. All the things that have become sort of the Dead Man Wear No Plaid sort of cliches. We tried to avoid all that, and reinvent it. But the influence, for me noir is a very moral parable, a very moral-oriented genre, which actually depends on the character's decisions to shape his destiny or her destiny.

I was very influenced by... And very rarely do you follow a character, that you don't know if there is any possibility of redemption in the character. The one that comes to mind immediately is Too Late For Tears. Lizabeth Scott is fantastic in that movie, because she is unstoppable, and we homage that movie by creating the same black bag with money that she has in the ending of that movie. There's Strangers on a Train, we homage the marque of the carnival, it's exactly the same marque. Then Robert Walker, walks in, in Strangers on a Train.

Other influences was Fallen Angel. The Otto Preminger, Fox Noir, the cafe on the beginning is sort of a riff on that. But mainly it was the Otto Preminger noirs at Fox were the main influence. You can see a very gritty, very dark reckoning morally, for those characters. I think that's what I wanted very much in this movie, that it felt like it addressed those moral questions of, what happens when you have a populist lie and lie all the way to the top, and then finding himself facing the truth at the end.

What was it about actually the Nightmare Alley material that said, "I want to remake this, this is something I want to spend two years, two or more years of my life making?"

DEL TORO: Almost four. Yeah, almost four. I think, first of all, I never, ever thought about it as a remake, because what I was trying to address was the novel. And not only the novel, but the biography of the writer of the novel, William Lindsay Gresham, which basically is the central character in Nightmare Alley. He left one of the notes, he left posthumously. It was, "I am Stan." Or, "Stan is me." And think when we were writing, Kim (Morgan) and I said, "Let's not refer are at all, to the first movie. Let's find our solutions through the novel and what we know about William Lindsay Gresham's spiritual quest," because he was in a quest. He's a guy that was looking into Buddhism, tarot, psychoanalysis, even early Dianetics. Yoga, physical culture. He was an incredibly curious mind, that fought on the Republican side, on the Lincoln Brigade in the Spanish Civil War. And that's where he heard about the geek, for the first time.

His wife left him and married C.S. Lewis, of Narnia fame. His life was, when he became very rich from Nightmare Alley, selling the rights, he spent it in a way that was completely irrational. But he was never completely happy, you felt. And part of it, what I wanted to show is a character that starts the movie with nothing, and then gains one, two, three times, possibilities of finding happiness. And he doesn't see them. He just thinks how, "There must be more, there must be more." And I always say, the idea of the Nightmare being the flip side of the American dream, that's what made me want to go do this movie.

That's one of the things that I loved about it is that, he's never satisfied.

DEL TORO: Never.

And it's amazing because he... I don't want to get into specifics obviously, but there's a clear point where he is very successful and has everything. Or has so much, and yet, it's never enough.

DEL TORO: No, there is in fact, one of the things that I loved in the novel, and that we were looking for very pointedly, is a happy ending in the middle. There's that beautiful crane, when he's leaving the carnival with the girl, the book, the code, everything. He has everything, to be happy. The crane goes to the sky, and it's almost like a happy ending. Then you cut, and it's two years later, he has a lot of money and he's incredibly unhappy. Still. And now he's unhappy with the girl that he thought was the reason to live, his reason to exist.

I thought, "This is a really interesting character, the idea of success," which is something that you grapple with as an artist and as a storyteller. The idea of, "Can you grapple with that and find happiness, not in what you have, but in what you don't lack?" That's a big difference. The enrichment is not the man that has a lot of money. It's the man that can give it, most of what he has, and be happy. These are questions that were in my mind, for the character.

For people that are younger movie fans that are not familiar with the film noir genre, what are some of the movies that they should start with if they want to engage with film noir?

DEL TORO: Well, I think the hardest noir is for me, the one that I like. I love Fallen Angel. I love Too Late for Tears, as I said. I love Detour. I love, in my opinion, all the Sam Fuller noirs are great. Where the Sidewalk Ends. Born to Kill, which is absolutely brutal, even now. There's curiosities, like there's two Micky Rooney noirs that are really unforgiving, with the main character. And they're very, very curious. I think that I would start with the hardest ones, because it's a genre that has a lot to offer in times of despair. That's the curious thing. It's a genre that should be very much in vogue, right now, because it's perfect for our times.

One of the things that I loved about Nightmare Alley is that, in all your movies, you tend to have monsters and creatures and everything else. But in this film, all the monsters are men.

DEL TORO: Yes.

And I loved that. Can you sort of talk about that aspect of the film?

DEL TORO: Well, look, the curious thing about Nightmare Alley is that it's at the same time, a big departure of what I do, and perfectly in keeping with what I do. In every movie, I always say, "The most brutal monster is man." And, I'm 57, and it was about time I tried to do it straight on. I tried to do it without any of the metaphors, and any of the parabolic figures of the monsters. And just go and portray the man.

The difficulty with a movie like this is that, you are following this character 99.9% of the time. We never lose sight of him. He is our guide in and out of every situation, every single scene. It comes out of him, or he goes into it. And that's a very difficult exercise, this is one of the things that made it so hard. How do we track this guy, where he is at, and what he's thinking? Look, it came to be so crazy an exercise that often I said, "We know more about this character, if we keep him in the shadows. We know what he's thinking more, if he's in the shadows or his back to us. And the camera just sees him thinking from behind."

These are devices we thought about, Bradley, the cinematographer, and myself. We said, "Let's try that." Because obviously you need the complicit partnership I have with Bradley, to do this. Because I would say, he would joke, that I would light put more light on the Cyclopean unborn baby than on him. I said, "Well, there's a little bit of truth to that, and these are the reasons." I think, and then we would joke with the cinematographer. We said, "No light. This is a closeup for Bradley." But I think that, but if you look at my characters and I think the caretaker in Devil's Backbone is sort of Stan. He's a prince without a kingdom, that believes he deserves more. The captain of Pan's Labyrinth is a little bit like that.

I think that, the only movie that comes to mind in the recent years is, There Will Be Blood, where you follow Daniel Plainview so meticulously. It's not an easy thing to do, you know?

I heard a rumor, and I want to know if it's true. First of all, Cate is fantastic in the movie, but I heard that the direction... That you had her acting like she was in a film noir, and everyone else was given different instructions. Is that true?

DEL TORO: Well, what I knew is that I needed a difference, between the first half and the second half. So what I said to Cate is, "You should move as if you are a big cat, like a tiger or a lion." That's how carefully she moves, in her space. Then, on the day I said, "And then we're going to crack that facade, a little bit." But I thought, in my mind, the carnival needed to be almost neo-realistic noir. And then, you go to the city, and with the city you get... Like, the carnival has a very small orchestration on the score, to give you an example. Then you go to the city, and the score becomes lush.

The carnival is full of warm colors, saturated reds, and there's no more red in the city. The only reds in the city are Molly's dress, blood, the lips of Lilith and the Salvation Army sign. That's it. You can watch the movie as many times as you want. And those are the only reds. And the elevator's light, I guess. But the idea is, all warmth is left behind. Therefore, the city is very well represented by straight lines, by cold textures, like steel, glass mirrors, polished black floors, and Lilith.

Lilith the character is the largest shark in the tank, in the sense that Stan thinks he's a big fish, and the city puts him on his rightful place. I wanted, with Cate to work in the more genre elements of the movie, to bring in sort of an evocation of all those great actresses in the '30s and '40s. To me, one of the things we discussed is, unlike the noir, traditional noir, the femme fatale meets a punishment, or something goes wrong. I said, "Let's make this an homme fatale, and let the three women not only survive him, but thrive after he's gone." And basically, the downfall occurs to him.

I thought, "Cate has a very difficult act balancing the icy surface and the moments of vulnerability and anger and pain, that the character has."

I love talking about the editing process, as you know, because that's ultimately where it all comes together.

DEL TORO: It's the typewriter. That's where you write the movie, for the first time.

Absolutely. You mentioned you had a longer cut. What was the cut you had that you're like, "I don't know how we're going to get this shorter." Do you know what I mean? Was it that 3 hour and 19 minute version? You're like, "Oh, this is really good."

DEL TORO: Yeah. Well, look, I was perfectly happy with the movie at 3 hours 15 minutes but I knew... Look, all it takes is to show it to somebody outside the circle. I think all it takes is, to show it to even 20 people, and you immediately feel the slowness, or the vagaries of the story. So, we had to lose approximately 40 minutes of the carnival and approximately 20, 30 minutes of the city, which was a big, big, big, big challenge.

I invited, as I always do, I invited the most immediate circle into the editing room, and show those things, try everything. My philosophy in the editing is, "You can and should try anything. And then, if you don't like it, you can always undo it." That's the advantage of the digital. Then we switch things from one place to another, and eventually ended up close to, or far away from, the original position of a scene or two that. But those are what I call hinges. If you move a hinge and the movie... Let's say, for example, on the beginning.

To give you an example, Stan went to work for Zeena a lot later than it is, right now. A lot of, more intervening scenes occurred, in the middle. And I said, "There is a progression there," we found if we move him forward and he's already working for her, really quick, there's a hinge. The audience goes, "Oh, that changed. That's it, there's some change." It's like a, "Now I'm ready to learn new things," as opposed to, "I'm still in the old scene."

I found that in the editing, it's not how long a movie is, it's how many steps are between A and B and B and C. The brisker those steps, the better the movie moves. And at 2 hours and 19 minutes it is the only movie I've done that is more than two hours.

I didn't even realize that.

DEL TORO: Yeah, I've never done more than two hours. I'm always 1 hour and 59 minutes and 59 seconds, max.

Will fans ever see the stuff you cut out?

DEL TORO: Look, I said it on the DVD of an earlier movie, I said, "The deleted scenes are deleted for a reason." And in the case of Nightmare Alley, they flesh out the character sometimes, in a direction that doesn't suit the rest of the narrative. If I could, in an ideal way, repace the movie, I would still pace it the way it is right now, because I think what you shoot and what you end up with, are two different things. If you wrote exactly the movie you shot, and you shoot exactly the movie you edited? A, I really would take exception to that. I would say it's all almost a really, it's a very purgatorial exercise.

I get it.

DEL TORO: I think when the movie talks, is when the movie is alive. For me, after 30 years of doing this, I find that the movies that are more worthy of tangling with, are the movies that talk back to you. And say, "We need this."

What was the last thing that you cut out before you picture locked, and why?

DEL TORO: I cut out little gestures. One of the things that I felt was extremely important, we knew that Stan was going to be silent for a long time, and his first words and where he speaks them for the first time was very crucial. And one of the last things that came out of the movie was, he used to say a small line before he talks to the geek, inside of the fun house. It felt too minor.

So, the ideal thing was to take it out and find a way for the scene to flow, without it. That was both challenging and fun, and that was the last thing. He had a very small line where he accepts the job, basically, that Ron Perlman offers him. And it was challenging to cut around it, but we did. When we go to the fun house, the first time he talks is in the dark, to the geek. Which is basically a mirror, of his future. The movie was pregnant with mirrors, circles, alleys. And it was so much better for me, that the first time he spoke, was in the darkness.

I've spoken to so many filmmakers, and they talk about how they wish they could have a break in the shoot to analyze the footage, see what they have, and then go forward. Unfortunately, with COVID, you shot for a little while, and then you had a very long break, and then you eventually started filming again. I'm curious, how did the film benefit from that shutdown, and how did things change as a result?

DEL TORO: Well, look, first of all, it's kind of difficult for me to see this without the disproportionate dimension of the pandemic we had. It put everything in perspective, first of all, it became about keeping yourself and people safe. And that gave the break a calendar. We thought first, "It's going to be nine weeks," and it wasn't. It was six months. And it was really, within that stopwatch, two things happened. I gained 60 pounds, from COVID routine, which meant you went from the sofa to the kitchen and back to the sofa for many, many months. Because we could not cross a border, it was locked down in Toronto. And that happened.

Then, the other thing that happened is, we were able to play with the material of the second half of the movie, which is what we shot first, for a longer, longer time. And Stan became clearer, and it became clearer what we needed on the first half, to see him become the guy that we had already shot. Bradley Cooper was able to lose about 15 pounds from the second half, to the first part. I found those 15 pounds and more. Rooney gave birth to a baby. And when she came back, she was a different Molly. Somebody more, that felt really connected to the earth, really grounded.

The structure of the second half made it clear that everything in the movie, everything in the movie was a prologue, to the last two minutes. The last closeup. It was written like that originally, in the screen blade it says, "And now comes the final shot," blah, blah, blah, "and the camera doesn't cut." But when you see the material, it became clear that everything was a prologue, to that moment.

Because, that's the biggest difference between the two versions, if you may. One of the biggest differences is, we see almost relief at the end, in his situation. He finally knows who he is, as opposed to the first version, which is an almost biblical punishment to him.

For people that are watching, I will not spoil the ending. I will just say, the ending is fucking awesome. And that shot is phenomenal. I don't want to say more than that, until people have seen it, but that is a shot. I was... I say, "Bravo, sir," on that final shot.

DEL TORO: It was very tempting to add this or add that, that's the thing... One of the things the movie did that was so curious, man, because I've never had that. I cut Shape of Water in silence, without temp score. And I cut this mostly without temp score, but it rejected score. The movie said, "No, no, no, no." And it took more than a year to find where and how much the score was needed.

The ending is so good in this, and it's because the whole movie is building towards that ending.

DEL TORO: The thing that... When you have a fantasy element, you have whimsical elements, that come with it. There is already an ingenuity in a character that doesn't exist or a situation that doesn't exist, that allows the mind to escape.

What happened in this movie is, actually we distill it as the movie goes, it becomes more and more distilled. Then, you start the movie with a guy alone, and you end the movie with a guy alone in a different way. For example, one element that was very, very much found in the editing, the dreams he has, were more... We shot much more. We could have revealed this and that, and connected... And we decided to make it a few images, that almost repeat themselves, and they add one to the other, to the other until you understand what happened in that cabin, in the opening shot.

And that was the other thing you say, "What was the last thing you subtracted, or added?" One, there was the second shot of the movie, which is not the shot that is there, was a beautiful crane. Gorgeous, gorgeous shot. It went from him, to his feet to a gasoline can, follow the trail of gasoline into a body. It was really amazing. It was the second shot of the movie, but it felt like a shot. It was so good, but it was very showy. And that went, because you could not start the movie like that. There was a power and a simplicity to the first shot, and then the shot of the burning cabin, that demanded sort a pared down sensibility to it.

I thought that you and Dan did such a great job, working together on the visual aesthetic of the film.

DEL TORO: Yeah.

And you've already touched on some of the colors and everything else, but could you sort of talk about a little bit more, the aesthetic of how you wanted the film to look, and working with Dan to achieve that?

DEL TORO: Well, one of the things that... When the movie is available for home, one of the things that I beg people if they can do it, is to watch the movie in black and white. Because what we did is, we used very traditional cross lighting, so the movie is lit like a black and white movie. It was art directed with a lot of reds and greens and gold, which gives you all the mid tones in the gray. So it was almost like a black and white movie, that was done in color. Like a serigraph. Imagine that you're printing the ink layer, that's the black and white, and then you print the color layer, that's the movie that you saw.

That was one of the things we said, "Let's do cross lighting, like in the traditional movies." We lowered the ceilings in a lot of the scenes, so the camera was able to see the characters and the ceiling, the ceilings were a little over six feet tall. So they were very present. Then, we decided to shoot the movie as much as possible, in oners. Like there's a lot of shots that are a single shot, and it's staged with the actors, like a movie from the '40s. Actors come close and away from the lens, the camera follows them, to and from a thing.

That is also a decision that has to do with the fact that, it's how this guy is illuminated by the characters. We thought, "Let Bradley be a negative space, like a black hole, lit by different characters." That, we give him three fathers and we give him three mothers, so to speak. And they illuminate him, in the middle, as a negative space. We needed to keep the integrity of that choreography to say, it's all about these interactions. It's not just about style, it's about, "Let's preserve the interaction between him and the characters."

You say, watching it in black and white. I would love to do that, but I don't necessarily know that, when it eventually comes out, maybe on Blu-ray. Because it's hard on the streamers, they generally don't give you that option.

DEL TORO: I would love to. Yeah. I would love to, and we are exploring the look of that. I watched, one of the things that happened during the pandemic, is that. I started watching the dailies when we came back, I watched them in black and white, on my MacBook. I went to gray scale and I watched them, I started watching all the dailies in black and white. I finally started to publicly say, "You guys should look at it this way," because that was how... Dan and I would squint in the monitor and love the lighting, because we were reproducing a very expressionist lighting in the nines, that was keeping all the mid tones.

I loved the cinematography and the look. One of the things that I felt, and I was saying this to someone is that, watching the movie I just felt transported to another time and place. I never thought about real life. I never thought about my phone. I just was captivated, beginning to end. One of the reasons is because the carnival is just so well-built and designed.

DEL TORO: Yeah.

I just disappeared into it. Can you sort of talk about creating that, on obviously, a budget? Because you're not making some Marvel movie with this material, you obviously have a finite amount of money.

DEL TORO: Yeah. I mean, in the last few years, you get period movies that cost up to 150, 160 million and we knew, we are a Searchlight movie, we had a budget that we needed to do by very judiciously building big sets, when it was needed. We had sets that were amazing. Lilith's office, Grindle's office, the Copacabana back, all the dressing rooms, and all that. But we also scouted very, very carefully. Then, what we decided early on with wardrobe, production design and the art department, they said, "Let's layer that really, really, really well. Let's not have just guys in suits and fedoras, and women city clothes."

We layered everything. I went on eBay, myself, and I started buying props and set dressing, that I brought to the movie that I made sure there was an accurate... I bought all the bills, all the cash that appears in the movie, I bought first. I wanted to find the cash that looked used. I got a lighting fixtures in Lilith's office, vending machines. When you go to a carnival, you have to get the period popcorn bags, the period balloons, the period strings for the balloons, the period carnival prices. If you see a Wall of kewpie dolls, you have to get kewpie dolls from the period. You have to get a period carnival merry-go-round. The fastenings on the tents are made of leather on brass. Leather on brass, machined for the period.

The way you hang the banners, everything. There was no modern hardware. All the kitchen, the cooking implements. Then we have to differentiate the way people dressed in the urban environment, in the city, and the way people dressed in the carnival. We used layers. We had people in leather jackets, we had people in denim jackets. We had women in working clothes. We had women in their best Sunday clothes. It was so layered. Then we had to choose every single prop, and run it against sort of, you would say a system, that qualified it and said, "Yeah, it's of the period. We cannot be inaccurate."

Then, just layering the props with the characters. All the women needed to have a little handbag. All the men needed to have a handkerchief, because back then you had to have it. And that's one of the things that I tell you... Two things, I'm marveled at Bradley, because I think this is a very different role than anything he's ever done. One of the first things I said to him is, "You have to take boxing." And he went into boxing lessons, and he was in the ring a couple of times a week, because I said, "If you went through depression, if you went through hopping trains in the '30s, you got physical. The way a guy that had been on the lam, or broke at that time, included the way he owned the physical space. And the way he would own a confrontation."

And he did it, he went full on. The other thing he did, which is absolutely marvelous to watch is, the way he handles cigarettes and the fedora. The way he puts it on, the way he folds it, straightens the brim, the way he picks it up. The way he picks up and holds a cigarette, which is completely of the period. He does it in two styles, the sophisticated smoker, in the second half, and the not-sophisticated smoker, in the first. And he kept track of all these little things. I tell you, those things are invaluable, the way you layer the period with not just the props and the sets, but the gestures. The way for example, Cate talks, is not an imitation. But she completely delivers a sort of mid Atlantic, very polished accent.

Oh, they're both fantastic. Do you think that Bradley, his experience directing, has changed him as an actor?

DEL TORO: No doubt. I mean, if you ask me, Bradley's a director that acts. It's a guy that you can talk... He knows exactly what the lens is looking at. Yes. That's one advantage, like he would say, "Do you want me to cross the lens?" He always stayed in the composition. He knew where the shot ended, and where his physical space started. All that is great. But also, what is amazing is, then you have a partner in the whole process. This is another guy that is worried about his part. He knows exactly where in the movie this is, what it means. Why do it in a oner, and not in coverage? Why there will be no close up here, or why he will reject the close up and say, "I think it played on the wide," and I go, "I think you're right. Let's move on."

This is, that's never happened to me. There was no wrangling expectations, because he knows where the direction is going. You're not wrangling the expectations of a star. You're actually, you have a full partner that understands editing, lighting, everything. I think we went through, we say this jokingly, we went through a 10 year friendship in three years. You know? We are now friends for life, and we've gone through every up and down there is in the book.

I know your hard at work at Pinocchio, and obviously I cannot wait to see it. For fans of yours, what would you like to tease them about the project? What do you want them to know about Pinocchio?

DEL TORO: Well, look, it's a very... It's a very, very, very, very personal movie for me. The two, the flip sides for me have always been Pinocchio and Frankenstein, are the same story. Because essentially that's the same story. The idea of a Pinocchio that talks about things that I consider very deep, but is fun and it's a musical, at the same time. But I find it really incredibly moving. Obviously, in animation, you get to see the movie in storyboards beginning to end many, many times, and then you add the stop motion. Right now, we are about 50% animated, and 50% in storyboards. Every time I watch the movie, I just sob like a baby. It's as personal as it gets, as moving as it gets, and it's unlike any other version of the story that you've ever seen. It's completely unlike it.

It subverts the moral underpinnings of the original fable which is, in order to be a real boy, you got to change. You've got to become flesh and blood. And you've got to become... This is about becoming a real boy, by acting. Or a real human, I would say, by acting like a real human. Period.

Do you think it'll be out, like a year from now?

DEL TORO: Oh yeah. The movie will come out last quarter of 2022. So it's curious because, it's been almost five years since Shape of Water, and now it's going to be two movies in a row, one after the other.

.jpg)