The 2001 anthrax attacks in the US are one of those feverish blips in the west’s collective psyche, a story that dominated the news for a few intense weeks then faded, pushed aside by the larger kerfuffle in the run-up to the invasion of Iraq. Seeing that Netflix now has a feature-length documentary entitled The Anthrax Attacks: In the Shadow of 9/11, you would be forgiven for saying: “Oh yeah. The anthrax thing. What was all that about?”

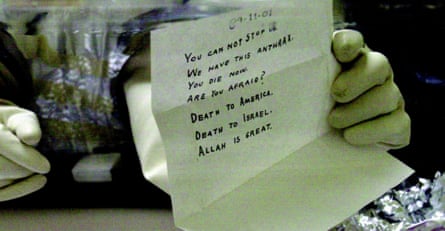

To recap: less than a month after the twin towers came down, a man called Bob Stevens died, having inhaled lethal anthrax spores. It was the first such fatality on US soil for a quarter of a century, but not too much was thought of it until eight days later, when NBC News in New York received a letter contaminated with anthrax. The note was dated 11 September and consisted of crude threats, scrawled in the spindly capitals of an unstable kidnapper or serial killer: “TAKE PENACILIN [sic] NOW. DEATH TO AMERICA. DEATH TO ISRAEL.” Similar letters were sent to the New York Post and two US senators; five people died, including two workers at a postal sorting office in Washington DC.

America panicked: 9/11 had been unimaginably horrific but it was a relatively isolated event, far away from most citizens. Now, with bio-terror’s answer to the Zodiac killer on the loose – either al-Qaida, or a copycat capitalising on the nation’s vulnerability for their own unknown reasons – it seemed anyone, anywhere could be in danger.

As this film combines archive footage and dramatic reconstructions with interviews with the relevant FBI agents, alongside others affected by the case, it is curious that it pays little attention to how useful the anthrax attacks were to a government already planning to use 9/11 and the fear of Islamic extremism to bolster support for attacking Iraq. But that is a minor objection. By focusing on the investigation itself, The Anthrax Attacks throws up plenty of rage-worthy injustices and tantalising mysteries.

FBI agents recall how, faced with one of the cases of their lives, they were put on the back foot: they needed guidance from scientific experts, but soon realised that access to the kind of anthrax the killer was using was limited to those same experts. After months of frustrated investigations and with the lethal letters having long since stopped, in June 2002 Dr Steven Hatfill was finally named as a person of interest, instantly turning him into a household name. The documentary sets out a pattern of events that is familiar from countless high-profile criminal investigations, where law enforcement and the media – sharing an interest in finding a culprit to vilify – leap on someone who fits the profile but against whom there is no substantial evidence. Hatfill suffered a prolonged period of intense scrutiny, during which the public were strongly encouraged to believe his guilt. Years later, he won $5.8m in compensation.

The film shows an admirable concern for the people who suffer when they become footnotes in a story with big stakes for the authorities. Colleagues and relatives of the two dead postal workers report how their workplace remained open for 10 days after anthrax contamination was suspected, the commercially valuable work of processing mail continuing even after investigators had appeared in the staff’s midst wearing full hazmat suits. The more rarefied offices of media organisations and senior politicians were shut down within hours, but their employees were better connected, better paid and, it’s impossible not to note despite it not being spelled out, white.

Back to the investigation, and the film finds a sly way to convey how cold the trail went for the FBI once the Hatfill fiasco was over: where once there were captions onscreen detailing specific dates, now we tick from 2003 to 2004 and 2005 without further news. Then, there’s a plot twist, and a new chief suspect – and if you’ve forgotten who it turned out to be, any experience of whodunnits makes it easy to guess. We get a further tale of law enforcement convinced they have their man, this time with both the circumstantial evidence and the character profile pointing more forcefully towards guilt. A bold shift into dramatised scenes, starring an excellent Clark Gregg as the mercurial, troubled accused, deftly sketches the character of a man who is either obviously the killer or someone susceptible to becoming a fall guy, depending on who is looking.

A bewitching, maddening true story – crisply told here – concludes with just the ending a fiction writer would choose if they wanted to explore how, when it matters most, official accounts of events have a spooky tendency to become incomplete. The 2001 anthrax attacks will probably return to our peripheral vision, naggingly unsettling but now a little closer to sharp focus.