History Should Remember Prince Felix Yusupov

The life of the complicated man who murdered Rasputin and changed Russia forever

Much like the ‘Mad Monk’ Iliodor, Prince Felix Yusupov seems to occupy that same space just outside of mainstream history: a footnote of the Russian revolution and a member of the supporting cast in the life of Grigori Rasputin. But it is worth looking further, to understand the man behind the murder that would define his legacy.

Yusupov was a character filled with complexity and almost constant contradiction.

He was a devoted husband and father, yet struggled with his sexuality his entire life. He longed to serve his country at the height of the war, yet was too idle and fearful to fight. He was a deeply religious man, yet he participated in the misguided killing of a holy man.

These contradictions of character came to a head in his involvement with Rasputin one mysterious and much-contested evening in late December 1916, which would go on to change Russia forever. Yusupov saw in himself a man of great historical importance, and this, as far as he was concerned, was how history would remember him. And in ways he never would have imagined, he was exactly right.

A rich boy’s world

The Yusupov family was an ancient one in Russia, intermingled in the aristocracy for hundreds of years. Over the generations they had grown extremely wealthy, even more so than the ruling Romanovs, owning seven palaces, 37 estates, various coal and iron mines, factories, mills and oil fields. So important was the family that when Princess Zinaida Yusupova (Felix’s mother) married Count Felix Felixovich Sumarkov-Elston (Felix’s father), the lesser Count was granted the title and surname of his wife, contrary to tradition, in order for the Yusupov name to stay alive.

Prince Felix Yusupov was born in 1887 in the Moika Palace, Saint Petersburg, the youngest of two boys, and proved flamboyant and rebellious from a young age. Being born into such wealth and extravagance, with the inevitable freedoms that came with it, he developed a slothful and self-entitled character. Felix was forever pushing the boundaries of what was deemed acceptable, often parading around in his mother’s clothing and jewellery, and attending balls and clubs dressed as a woman to trick men for his own amusement. He seemed to take immense pleasure in scandalising high society with his adventures, earning a reputation as a bit of a playboy and a wildcard.

Although he denies it in his own memoirs, multiple sources claim Felix was actually bisexual, having various sexual partners in his youth, both men and women. Although this side of him calmed down after marriage, rumours of his ambiguous sexuality persisted for decades after.

But aside from a rebellious nature, Felix also possessed a charitable heart, and when his elder brother Nikolai died in a duel in 1908, leaving him the sole heir to his family’s vast fortune, the grieving young Prince threw himself in to charity work, and once threatened to give everything away to the poor. Of course, he didn’t, being persuaded against it by his mother, who had power over Felix like no other, but despite his many flaws, he would remain generous with his wealth (often to the point of recklessness) for the rest of his days.

Felix was straightened out of such charitable behaviour by being shipped off to Oxford for his education, where he embraced his freedoms, recaptured his status as a Russian playboy, and held all manner of wild parties with the elite of European society. This was the young Felix in his element and possibly at his happiest. He remained in England for his studies (though he was more interested in the parties) between 1909 and 1912.

Returning home, perhaps being reminded of his duties by his mother (the death of his brother also meant the sole inheritance of the Yusupov name), Felix met and fell for Princess Irina Alexandrovna, a member of the Russian royal family. Irina was considered one of the great beauties of her time, but it is, perhaps, somewhat of a glimpse into his sexual uncertainty that Felix said the following in his memoirs recalling his first impression of her:

“She had beautiful features… and looked very like her father.”

The couple were engaged in 1913, but Irina’s parents opposed the marriage, all too aware of Felix’s wild past. Possibly stirring up these rumours was a man that was also competing for Irina’s hand, and who would go on to play a big part in Felix’s life: Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich. Rumour has it he and Felix had a romantic relationship at one point, but either way, Dmitri thought himself a better match for Irina and made his intentions known. Felix himself had his own doubts about whether he was cut out for married life, perhaps wondering whether he was ready to give up his debauched lifestyle. But in the end, Felix and Irina married in 1914, in what was the last, great spectacle wedding of the Russian Empire.

Despite all the challenges that would follow, and the initial hesitations and objections, it would prove to be a very successful marriage spanning five decades.

On the big day, Irina wore Marie Antoinette’s veil and was given away by her uncle, Tsar Nicholas II, who gifted the couple a bag of 29 uncut diamonds as a wedding present.

Six months after their wedding saw the outbreak of World War I. The Yusupovs were honeymooning in Europe at the time, and were briefly detained in Berlin (albeit ‘detained’ in an extravagant palace of their choosing).

In March 1915, while the war in Europe was raging, the couple had their only child, a daughter (Irina) nicknamed Bébé. Felix adored her, yet she was raised largely by nursemaids and servants themselves. Neither Felix nor Irina did much of the parenting, leaving Bébé in the hands of her grandparents for most of her formative years.

Felix had more pressing matters on his mind that were distracting him. He saw in himself a great and important man whose name would one day be written down in history, and recognised with the substantial means and influence at his disposal, that he had all the tools to make this happen. Yet battling against this was his generally spoiled and idle nature.

As the war intensified, he wanted to serve his country, signing up for an officer’s training course. But Felix didn’t have the stomach for war and wasted little time taking advantage of a loophole barring only sons from serving, much to the mirth of those around him (with exception of his wife and mother). This didn’t stop him from walking around in his officer’s uniform though, liking how he looked and what it represented, but not liking the responsibility that was attached to it. Tsar Nicholas II’s eldest daughter, the Grand Duchess Olga (first cousin of Irina) visited the Yusupovs sometime in 1915 and wrote to her father expressing this sentiment:

“Felix is a ‘downright civilian,’… [he] walked to and fro about the room, searching in some bookcases with magazines and virtually doing nothing; an utterly unpleasant impression he makes — a man idling in such times.”

He went on to convert a wing of one of his palaces in to a hospital to treat wounded soldiers — a noble endeavour certainly, but this didn’t satisfy him for long, and he grew restless still. He wanted to do more. He wanted to get his hands dirty.

How was a man such as Felix to serve his country at a time of war, if not on the battlefield?

Murdering Rasputin

Around the time his daughter was born, in 1915, Felix started to pay visits to Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin, wanting help to cure an undisclosed ‘malady’. Rasputin had already been circling around Saint Petersburg society for a decade at this point, establishing a paradoxical reputation as both a man of God and possessor of healing powers, and also a perverted alcoholic, sex addict, and master of the dark arts.

Why Felix visited him is not known, but in his memoirs he claims it was to ingratiate himself with Rasputin for what would follow, suggesting he was already plotting his murder, which was certainly not true. Many have speculated that Felix was actually visiting him hoping to cure his own homosexual desires.

But whatever the reason, it is clear that Felix did so as a genuine believer in Rasputin’s healing powers, only changing his mind when public sentiment, and the opinion of those he looked up to and respected, kicked up their anti-Rasputin agenda and the media started to portray him firmly as the devil-incarnate.

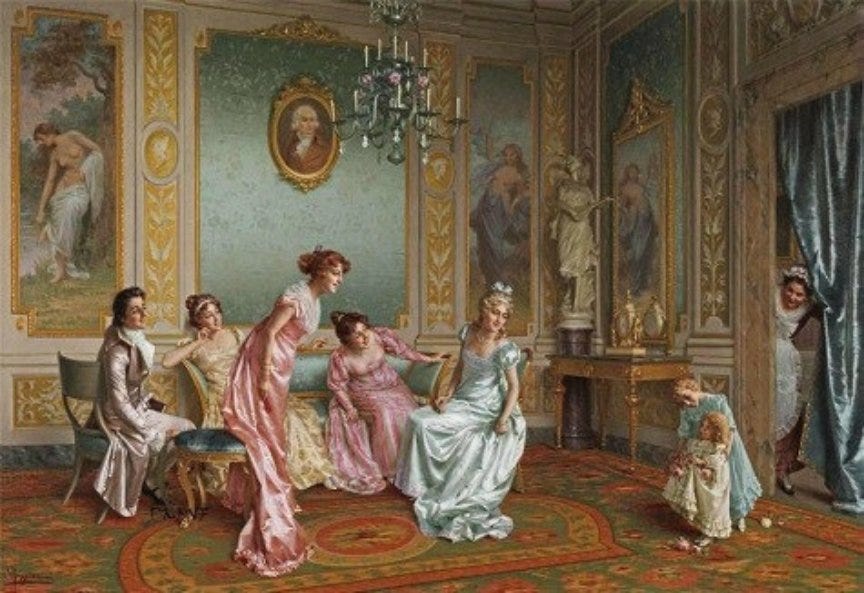

Initially, Rasputin was an amusement and curiosity, something to be gawped at in the parlours of the wealthy, but this soon made way to outright disdain as he grew closer to the Imperial family, and his apparent power grew.

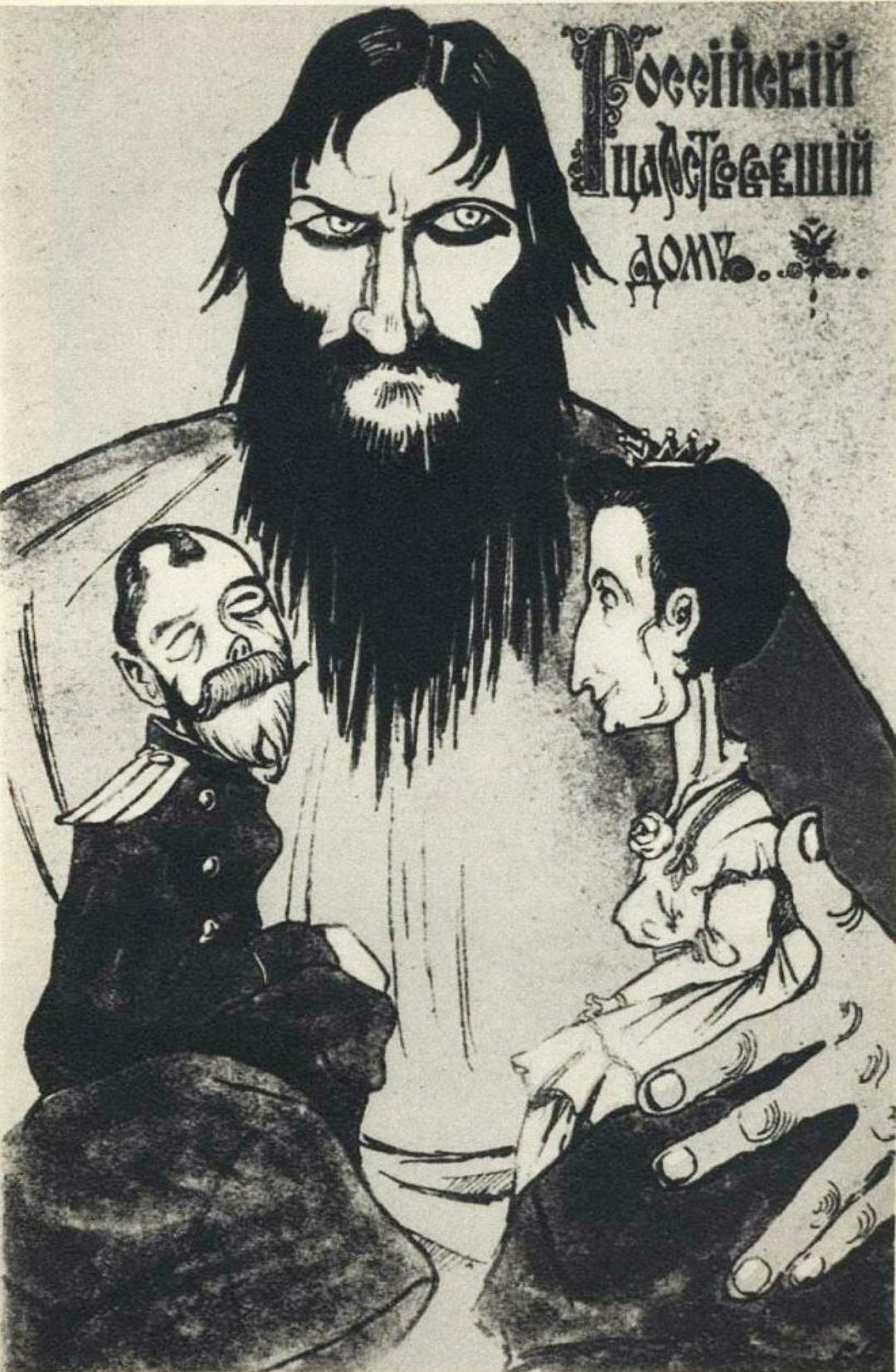

The Tsar and Tsarina found him essential as the only man able to heal their sickly son and sole heir Alexei, a haemophiliac often at death’s door. As WWI rolled on and Russia’s failings were being highlighted with each passing day, Tsar Nicholas II moved to the front to command the army himself, hoping to turn things around, leaving his already hated wife, Tsarina Alexandra, to run the day to day in his absence (who was, mind you, a German ruling Russia during a war against Germany). The Tsarina had a very close relationship with Rasputin and considered him a Christ-like figure, keeping clippings of his hair as tokens, and cherishing every word he uttered, whether spiritual or political, resulting in much of the governance of Russia coming, indirectly, from a Siberian peasant, much to the dismay of the aristocracy.

This is fundamentally how the fall of the Russian Empire came about: an already crumbling political system of autocracy, with a weak and absent autocrat, challenged on all sides within the confines of a world war by rumour, and sitting on top of it all was the bomb of Grigori Rasputin, whom the aristocracy wanted rid of at any cost, and the revolutionaries were happy to use to their advantage.

Felix Yusupov, without realising, became the man to light this bomb.

Quite when Felix first decided to kill Rasputin is not known, but Douglas Smith, in his biography Rasputin, points out that it may have been due to a letter from his mother. In October 1915, Princess Zinaida wrote to her son about the rumours surrounding the Imperial family, remarking:

“I disdain everyone who tolerates this and remains silent!”

Felix adored his mother and wanted to please her at all costs, so perhaps this is where the idea first planted itself in his head, the idea that would also ultimately give him what he wanted and prove to himself his own historical importance.

He certainly wasn’t the only one to think Rasputin needed to be eliminated. There had already been multiple attempts and conspiracies against Rasputin’s life over the years, all of which had been botched or uncovered. But gone were the days where these things contained themselves to the underground via coded letters and whispers and secretive plotting — people were now talking openly and freely about their desires for Rasputin’s death and how it might be achieved. Peasants, the media, high ranking officials, members of the royal family, and even the Church, all publicly called for his murder.

Felix believed he was the man for the job, but knew he needed help, and a plan, and enlisted a troupe of conspirators: right-wing politician and anti-Semite Vladimir Purishkevich (who brought himself to prominence in parliament by delivering a rousing speech in which he called for Rasputin to be killed), Dr Stanislaus de Lazovert, his old personal friend Lieutenant Sergei Mikhailovich Sukhotin, and the aforementioned Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, whose presence the others hoped would be enough to show this was not an act against the royal family.

The group’s vision was simple (and naive). In their eyes, the death of Rasputin would allow the Tsar and Tsarina to break free from the fictional spell they were under, the Tsar would return and regain control of the country and, free from outside corruption at last, the war effort could be concluded with success, with the royal family then recapturing the trust of the people, and Felix and the other conspirators being heralded as heroes for their great act of patriotism.

Needless to say, while the group did succeed in killing Rasputin, in every other way the plan was a disaster.

But how would they kill such a public, instantly recognisable and heavily protected man as Grigori Rasputin? Well, accounts from this point forward are shaky at best, with many of the sources depicting the events of Rasputin’s murder needing to be taken with a pinch of salt, as it comes from those directly involved who all attempt to justify and excuse the murder, and cover up their own ineptitude. In the case of Felix’s own account, which has become the most commonly told version of events and sparked various movies and TV dramas, several handfuls of salt are required.

According to Felix, he used his previous acquaintance with Rasputin to lure him to his home on the promise he would introduce him to Irina, whom Rasputin had supposedly wanted to meet for some time. Just after midnight on the 30th December 1916, Felix picked up Rasputin from his home in a car driven by Dr Stanislaus, and drove to his Moika Palace. They arrived with music playing from upstairs (apparently the Yankee Doodle on repeat) and Felix told Rasputin to wait in the newly built basement as a party upstairs was just finishing, and his wife would see him afterwards. Irina was actually in Crimea on doctor’s orders and the party was staged: the plan here was to poison him.

Irina, as a side note, was fully aware of the plot, and this we know for certain by a series of letters between the couple. Felix wanted her to be present and involved in the plot, using her as bait, and although she thought the whole thing insane Irina was willing to help, but due to her health insisted that Felix delay things until her return, which he refused.

None the wiser, Rasputin agreed to wait downstairs with Felix (with the other conspirators all waiting nervously upstairs), and was fed cream cakes and wine laced with potassium cyanide, enough to fell an elephant, which Rasputin gobbled down greedily.

He was drunk within an hour, but apparently proved resistant to the poison, which Felix claimed must have been due to his supernatural powers. If poison was actually involved at all, it is thought that the poison had either expired and become ineffectual (which would make sense given the general incompetence of the group’s plot) or the supplier of the poison had second thoughts and the cakes and wine were untainted, unbeknownst to Yusupov and company.

Either way, growing increasingly nervous and convinced Rasputin knew what was going on, Felix excused himself saying he was checking on his wife, and ran upstairs to confer with the others. It was imperative that Rasputin be killed tonight, so they had time to dispose of the body before dawn. So Felix took Dmitri’s browning pistol (as the story goes), went back downstairs, and saw Rasputin looking at a crucifix on the wall.

“Grigori Yefimovich, you’d better look at that crucifix and say a prayer,” Felix claims to have said, in a quip befitting an action movie star, and then as Rasputin turned, he shot him in the stomach. Rasputin dropped to the floor, and the others ran downstairs to see. The doctor declared him dead and they all headed back upstairs to celebrate and plan their next move.

The men staged their alibi, with Sukhotin wearing Rasputin’s coat and hat, and being driven back to his house to make it seem to any onlookers or people following them that Rasputin made it home that night safe and sound. They then returned to the Moika Palace to dispose of the body, but when Felix checked on Rasputin, despite not feeling a pulse, he claims the holy man leapt up and began throttling him. Felix later wrote:

“It was the reincarnation of Satan himself who held me in his clutches and would never let me go till my dying day.”

But Rasputin did let him go, and dashed out of a door to try and escape, making it into the courtyard. Felix alerted the others and Vladimir Purishkevich pulled out his own gun and shot Rasputin twice more, finally killing him. They cleaned up the best they could, drove the body to the Malaya Nevka river and tossed the body into an opening in the ice, forgetting to attach the weights to him first so he would sink. They also noticed that one of Rasputin’s boots had fallen off, so they simply tossed this in after him, missing the water. Nevertheless, convinced the job was a success, they drove home.

Whatever happened inside the Moika Palace, Rasputin certainly did burst out onto the courtyard, as blood was found and gunshots heard. The autopsy revealed a point-blank shot to Rasputin’s forehead, however, and wounds inflicted by blunt objects, possibly a dumbbell, but these facts are left out of Felix’s memoirs.

Two policemen visited in the early hours to investigate the gunshots. The first was simply told that they had drunkenly shot a dog and there was nothing to worry about. However, the second policeman, who was following up on the first, was told by Purishkevich that the men had killed Rasputin for the good of the country, and that he should keep it secret, which the policeman agreed, but upon leaving, immediately reported it to his superiors.

Why Purishkevich would admit this to a policeman so soon after seems strange, but all the men were well-off members of high society, so in their mind they couldn’t possibly be punished for the killing of a mere Siberian peasant, let alone one that almost everyone despised. And in this, they were entirely correct.

An investigation began within a few hours, and the media began reporting later that very afternoon that Rasputin had disappeared. Two days after the murder, on 1st January 1917, the body was found, fished out of the water not too far from where it had been disposed.

Tsarina Alexandra was understandably furious, as was Tsar Nicholas II when he got word. By this point Purishkevich and Sukhotin had already left for the front, so all eyes of the investigation landed on the young Prince and Grand Duke. Both were put under house arrest and continued to deny they had anything to do with it, repeating the story about the shot dog, but in the end they admitted what had happened. Alexandra wanted both men shot, but in the end the pair got off lightly, and the Tsar dished out the ‘punishments’, with Dmitri being sent off to the front in Persia, and Felix merely getting banished to one of his lesser estates.

This bunch of conspiring elites had just murdered a man and been excused by the Tsar, signal enough to the hungry and bitter people that it was high time to change.

Within two months of the murder the revolutionaries, emboldened by the apparent challenge of the autocrat’s power and his weak response, rose up in what is known as the February Revolution, which ended with Tsar Nicholas II abdicating the throne on 15th March 1917 ending 304 years of Romanov rule. Nicholas, Alexandra, and their five children were put under house arrest and eventually executed by a Bolshevik firing squad in July 1918.

Prince Felix Yusupov’s plan to save Russia and paint himself as a hero had backfired tremendously.

Exile and aftermath

After having their palace seized by the Bolsheviks and understandably fearing for their lives, the Yusupovs fled to Yalta, Crimea, where on the 7th April 1919 the British warship HMS Marlborough evacuated them and 80 or so other Russians, including the remaining few members of the Romanov family. None of those on board would ever see Russia again.

According to the British officers, despite everything, Felix bragged shamelessly about his part in the murder of Rasputin throughout the trip.

The Yusupovs departed in Malta, eventually travelling on to Italy, Paris, then London. But this was far from a European tour. The mood was sombre and filled with uncertainty. To sustain themselves financially, they took various jewels and some original Rembrandt paintings, which they had managed to smuggle out when fleeing and sold to continue their passage. On arriving to Italy, lacking a Visa, Felix had to bribe some officials with diamonds to let them enter.

While briefly in London, Felix was reunited with his co-conspirator and friend Grand Duke Dmitri, but Dmitri wanted nothing to do with him, upset that he would be so open and boastful about the murder, despite a pact being made between the two to never discuss it. For Dmitri, it was a stain on his conscience, while for Felix, though the outcome did not go as they hoped, it was still a heroic act of which he was proud and held no regrets.

The Yusupovs settled in Paris from 1920 and remained there for the rest of their lives. The couple started a fashion house called IRFE (the first two letters of both their names) in 1924 which went bust after the Wall Street crash of 1929. True to character, a combination of overspending, poor financial management, and excessive financial generosity within the Russian émigré population burned through the remaining family wealth. Scandal and drama followed, as Felix was reportedly ‘caught in the act’ with the underage son of a prominent French politician in 1928, whom he paid hush money to keep the matter out of court.

Felix had no qualms in exploiting his actions and infamy to financially support his family for the decades that followed, writing two books that went into grisly detail about the murder. One of them caused Rasputin’s daughter Maria to sue him for damages, but the French court didn’t want to get involved in Russian politics, and so nothing came of it. In perfect hypocrisy, Felix himself sued various media outlets that portrayed him or Irina in a negative light, winning several lawsuits over plays and movies. One of these lawsuits against MGM in 1933 resulted in a huge payout and the “all persons fictitious” disclaimer we now see in almost every American film. After winning the case, Felix told reporters: “you cannot imagine the torture I went through reliving the killing of Rasputin.” While on the face of it this seems a blatant lie, there is perhaps some truth to it, as he was said to be haunted by nightmares about the murder in his later years, finally coming to terms with what he had done.

He published his memoirs Lost Splendour in 1953, which remains an unreliable yet fascinating source of information about one of the most important parts of Russian history.

Prince Felix Yusupov died in 1967, age 80, followed three years later by a grief-stricken Irina. Despite his personal contradictions and the many external challenges they both faced, the couple enjoyed a long and happy marriage of over 50 years: perhaps the one consistently positive element in Felix’s strange and complicated life.

While he is not remembered today as the man of great historical importance that he always imagined and believed he would, his contribution and role in history cannot be questioned. Indeed, if Felix Yusupov did not kill Rasputin, someone else would have, and the revolution that had been threatening to bring down the autocracy seems inevitable in hindsight.

Nevertheless, he did pull the trigger and in doing so he was the one to light that inevitable fuse he had no intention in lighting. While in his youth he was described as a Russian playboy, his legacy today is one of a poster boy of the late Russian Empire: a selfish, spoiled, impudent, and out of touch aristocrat, who simply helped bring down the very thing he tried to save.

Sources

Lacio, Irina, (undated). Felix Yusupov and Princess Irina of Russia: love, riches and emigration. Afisha London. Available at: https://afisha.london/en/2021/02/12/felix-yusupov-and-princess-irina-of-russia-love-riches-and-emigration/

Smith, Douglas, 2017. Rasputin. London: Pan Macmillan.

Simkin, John, 1997 (updated 2020). Felix Yusupov. Spartacus Educational Publishers Ltd. Available at: https://spartacus-educational.com/RUSyusupov.htm

Yusupov, Prince Felix, 1953. Lost Splendour, London: Jonathan Cape.