Shanghai

Last updatedShanghai 上海 | |

|---|---|

| Municipality of Shanghai | |

Skyline of Lujiazui from Zhapulu Bridge | |

| Etymology: 上海浦 (Shànghăi pǔ) "The original name of the Huangpu River | |

| |

Location of Shanghai Municipality in China | |

| Coordinates(People's Square): 31°13′43″N121°28′29″E / 31.22861°N 121.47472°E | |

| Country | China |

| Region | East China |

| Settled | c. 4000 BC [1] [ dubious ] |

| Establishment of - Qinglong Town | 746 [2] |

| - Huating County | 751 [3] |

| - Shanghai County | 1292 [4] |

| - Municipality | 7 July 1927 |

| Municipal seat | Huangpu District |

| Divisions - County-level - Township- level |

|

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality |

| • Body | Shanghai Municipal People's Congress |

| • CCP Secretary | Chen Jining |

| • Congress Chairwoman | Huang Lixin |

| • Mayor | Gong Zheng |

| • Municipal CPPCC Chairman | Hu Wenrong |

| • National People's Congress Representation | 57 deputies |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 6,341 km2 (2,448 sq mi) |

| • Water | 653 km2 (252 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 14,922.7 km2 (5,761.7 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 4 m (13 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 118 m (387 ft) |

| Population (2022) [9] | |

| • Municipality | 26,875,500 |

| • Rank | 1st in China |

| • Density | 4,200/km2 (11,000/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 40,000,000 |

| • Metro density | 2,700/km2 (6,900/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Shanghainese |

| GDP [11] | |

| • Municipality |

|

| • Per capita |

|

| Time zone | UTC+08:00 (CST) |

| Postal code | 200000–202100 |

| Area code | 21 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-SH |

| – Growth | |

| HDI (2021) | 0.880 [12] (2nd) – very high |

| License plate prefixes |

|

| Abbreviation | SH / 沪 (Hù) |

| City flower | Yulan magnolia |

| Languages | |

| Website | |

Shanghai [lower-alpha 1] is one of the four direct-administered municipalities of China. The city is located on the southern estuary of the Yangtze River, with the Huangpu River flowing through it. The population of the city proper is the third largest in the world, with around 29.2 million inhabitants in 2023, while the urban area is the most populous in China, with 39.3 million residents. As of 2022, the Greater Shanghai metropolitan area was estimated to produce a gross metropolitan product (nominal) of nearly 13 trillion RMB ($1.9 trillion). [14] Shanghai is one of the world's major centers for finance, business and economics, research, science and technology, manufacturing, transportation, tourism, and culture. The Port of Shanghai is the world's busiest container port.

Contents

- Etymology

- Alternative names

- History

- Antiquity

- Imperial era

- Rise and golden age

- Japanese invasion

- Modernity

- Geography

- Climate

- Cityscape

- Politics

- Structure

- Administrative divisions

- Economy

- Finance

- Manufacturing

- Tourism

- Free-trade zone

- Demographics

- Religion

- Language

- Education and research

- Transport

- Public

- Roads and expressways

- Railways

- Air and sea

- Culture

- Museums

- Cuisine

- Arts

- Fashion

- Sports

- Environment

- Parks and resorts

- Air pollution

- Environmental protection

- Media

- International relations

- Twin towns – sister cities

- Consulates and consulates general

- See also

- Notes

- References

- Further reading

- External links

Originally a fishing village and market town, Shanghai grew in importance in the 19th century due to both domestic and foreign trade and its favorable port location. The city was one of five treaty ports forced to open to European trade after the First Opium War which ceded Hong Kong to the United Kingdom, following the Second Battle of Chuenpi in 1841, more than 60 km (37 mi) east of the Portuguese colony of Macau that was also controlled by Portugal following the Luso-Chinese agreement of 1554. The Shanghai International Settlement and the French Concession were subsequently established. The city then flourished, becoming a primary commercial and financial hub of Asia in the 1930s. During the Second Sino-Japanese War, the city was the site of the major Battle of Shanghai. After the war, the Chinese Civil War soon resumed between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), with the latter eventually taking over the city and most of the mainland. From the 1950s to the 1970s, trade was mostly limited to other socialist countries in the Eastern Bloc, causing the city's global influence to decline during the Cold War.

Major changes of fortune for the city would occur when economic reforms initiated by paramount leader Deng Xiaoping during the 1980s resulted in an intense redevelopment and revitalization of the city by the 1990s, especially the Pudong New Area, aiding the return of finance and foreign investment. The city has since re-emerged as a hub for international trade and finance. It is the home of the Shanghai Stock Exchange, one of the largest stock exchanges in the world by market capitalization and the Shanghai Free-Trade Zone, the first free-trade zone in mainland China. Shanghai has been classified as an Alpha+ (global first-tier) city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network. As of 2022, it is home to 12 companies of the Fortune Global 500 and is ranked 4th on the Global Financial Centres Index. The city is also a global major center for research and development and home to numerous Double First-Class Universities. The Shanghai Metro, first opened in 1993, is the largest metro network in the world by route length.

Shanghai has been described as the "showpiece" of the economy of China. Featuring several architectural styles such as Art Deco and shikumen, the city is renowned for its Lujiazui skyline, museums and historic buildings including the City God Temple, Yu Garden, the China Pavilion and buildings along the Bund, which includes Oriental Pearl Tower. Shanghai is also known for its cuisine, local language, and cosmopolitan culture, ranks sixth in the list of cities with the most skyscrapers, and it is one of the biggest economic hubs in the world.

Etymology

| Shanghai | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Shanghai" in regular Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 上海 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Shànghǎi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Shanghai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Upon the Sea" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The two Chinese characters in the city's name are 上 (shàng/zaon,"upon") and 海 (hǎi/hé,"sea"),together meaning "On the Sea." The earliest occurrence of this name dates from the 11th-century Song dynasty,when there was already a river confluence and a town with this name in the area. How the name should be understood has been disputed,but Chinese historians have concluded that during the Tang dynasty,the area of modern-day Shanghai was under sea level,so the land appeared to be literally "on the sea." [15]

Shanghai is officially abbreviated 沪 [lower-alpha 2] (Hù/wu) in Chinese,a contraction of 沪渎 [lower-alpha 3] (HùDú/wu-doq,"Harpoon Ditch"),a 4th- or 5th-century Jin name for the mouth of Suzhou Creek when it was the main conduit into the ocean. [18] This character appears on all motor vehicle license plates issued in the municipality today. [19]

Alternative names

申 (Shēn/sén) or 申 城 (Shēnchéng/sén-zen,"Shen City") was an early name originating from Lord Chunshen,a 3rd-century BC nobleman and prime minister of the state of Chu,whose fief included modern Shanghai. [18] Shanghai-based sports teams and newspapers often use Shen in their names,such as Shanghai Shenhua and Shen Bao .

华 亭 [lower-alpha 4] (Huátíng/gho-din) was another early name for Shanghai. In AD 751 during the mid-Tang dynasty,Huating County was established by Zhao Juzhen,the governor of Wu Commandery,at modern-day Songjiang,the first county-level administration within modern-day Shanghai. The first five-star hotel in the city was named after Huating. [20]

魔 都 (Módū/mó-tu,"Magical City"),a contemporary nickname for Shanghai,is widely known among the youth. [21] The name was first mentioned in Shōfu Muramatsu's 1924 novel Mato,which portrayed Shanghai as a dichotomous city where both light and darkness existed. [22]

The city has various nicknames in English,including the "New York of China",in reference to its status as a cosmopolitan megalopolis and financial hub, [23] the "Pearl of the Orient",and the "Paris of the East." [24] [25] This is similar to Ho Chi Minh City (also known as Saigon),in Vietnam,which has also been nicknamed as "Paris of the Orient," due to Vietnam's historical French status. [26]

History

Antiquity

The western part of modern-day Shanghai was inhabited 6,000 years ago. [27] During the Spring and Autumn period (approximately 771 to 476 BC),it belonged to the Kingdom of Wu,which was conquered by the Kingdom of Yue,which in turn was conquered by the Kingdom of Chu. [28] During the Warring States period (475 BC),Shanghai was part of the fief of Lord Chunshen of Chu,one of the Four Lords of the Warring States. He ordered the excavation of the Huangpu River. Its former or poetic name,the Chunshen River,gave Shanghai its nickname of "Shēn." [28] Fishermen living in the Shanghai area then created a fish tool called the hù,which lent its name to the outlet of Suzhou Creek north of the Old City and became a common nickname and abbreviation for the city. [29]

Imperial era

During the Tang and Song dynasties,Qinglong Town (青龙镇 [lower-alpha 5] ) in modern Qingpu District was a major trading port. Established in 746 (the fifth year of the Tang Tianbao era),it developed into what was historically called a "giant town of the Southeast," with thirteen temples and seven pagodas. Mi Fu,a scholar and artist of the Song dynasty,served as its mayor. The port experienced thriving trade with provinces along the Yangtze and the Chinese coast,as well as with foreign countries such as Japan and Silla. [2] By the end of the Song dynasty,the center of trading had moved downstream of the Wusong River to Shanghai. [30] It was upgraded in status from a village to a market town in 1074,and in 1172,a second sea wall was built to stabilize the ocean coastline,supplementing an earlier dike. [31] From the Yuan dynasty in 1292 until Shanghai officially became a municipality in 1927,central Shanghai was administered as a county under Songjiang Prefecture,which had its seat in the present-day Songjiang District. [32]

Two important events helped promote Shanghai's developments in the Ming dynasty. A city wall was built for the first time in 1554 to protect the town from raids by Japanese pirates. It measured 10 m (33 ft) high and 5 km (3 mi) in circumference. [33] A City God Temple was built in 1602 during the Wanli reign. This honor was usually reserved for prefectural capitals and not normally given to a mere county seat such as Shanghai. Scholars have theorized that this likely reflected the town's economic importance,as opposed to its low political status. [33]

During the Qing dynasty,Shanghai became one of the most important seaports in the Yangtze Delta region as a result of two important central government policy changes:in 1684,the Kangxi Emperor reversed the Ming dynasty prohibition on oceangoing vessels—a ban that had been in force since 1525;and in 1732,the Qianlong Emperor moved the customs office for Jiangsu province ( 江 海 关 ; [lower-alpha 6] see Customs House,Shanghai) from the prefectural capital of Songjiang to Shanghai,and gave Shanghai exclusive control over customs collections for Jiangsu's foreign trade. As a result of these two critical decisions,Shanghai became the major trade port for all of the lower Yangtze region by 1735,despite still being at the lowest administrative level in the political hierarchy. [34]

- Songjiang Square Pagoda,built in the 11th century

- The Mahavira Hall at Zhenru Temple,built in 1320

- The walled Old City of Shanghai in the 17th century

Rise and golden age

In the 19th century,international attention to Shanghai grew due to European recognition of its economic and trade potential at the Yangtze. During the First Opium War (1839–1842),British forces occupied the city. [35] The war ended in 1842 with the Treaty of Nanking,which opened Shanghai as one of the five treaty ports for international trade. [36] The Treaty of the Bogue,the Treaty of Wanghia,and the Treaty of Whampoa (signed in 1843,1844,and 1844,respectively) forced Chinese concession to European and American desires for visitation and trade on Chinese soil. Britain,France,and the United States all established a presence outside the walled city of Shanghai,which remained under the direct administration of the Chinese. [37]

The Chinese-held Old City of Shanghai fell to rebels from the Small Swords Society in 1853,but control of the city was regained by the Qing government in February 1855. [38] In 1854,the Shanghai Municipal Council was created to manage the foreign settlements. Between 1860 and 1862,the Taiping rebels twice attacked Shanghai and destroyed the city's eastern and southern suburbs,but failed to take the city. [39] In 1863,the British settlement to the south of Suzhou Creek (northern Huangpu District) and the American settlement to the north (southern Hongkou District) joined in order to form the Shanghai International Settlement. The French opted out of the Shanghai Municipal Council and maintained its own concession to the south and southwest. [40]

The First Sino-Japanese War concluded with the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki,which elevated Japan to become another foreign power in Shanghai. Japan built the first factories in Shanghai,which was soon copied by other foreign powers. All this international activity gave Shanghai the nickname "the Great Athens of China." [41] In 1914,the Old City walls were dismantled because they blocked the city's expansion. In July 1921,the Chinese Communist Party was founded in the French Concession. [37] On 30 May 1925,the May Thirtieth Movement broke out when a worker in a Japanese-owned cotton mill was shot and killed by a Japanese foreman. [42] Workers in the city then launched general strikes against imperialism,which became nationwide protests that gave rise to Chinese nationalism. [43]

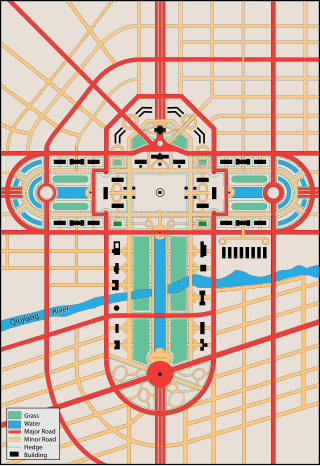

The golden age of Shanghai began with its elevation to municipality after it was separated from Jiangsu on 7 July 1927. [37] [44] This new Chinese municipality covered an area of 494.69 km2 (191.0 sq mi),including the modern-day districts of Baoshan,Yangpu,Zhabei,Nanshi,and Pudong,but excluded the foreign concessions territories. [44] Headed by a Chinese mayor and municipal council,the new city government's first task—the Greater Shanghai Plan—was to create a new city center in Jiangwan town of Yangpu district,outside the boundaries of the foreign concessions. The plan included a public museum,library,sports stadium,and city hall,which were partially constructed before being interrupted by the Japanese invasion. [45] In the 1920s, shidaiqu became a new form of entertainment and was popularised in Shanghai. [46]

The city flourished,becoming a primary commercial and financial hub of the Asia-Pacific region in the 1930s. [47] During the ensuing decades,citizens of many countries and all continents came to Shanghai to live and work;those who stayed for long periods—some for generations—called themselves "Shanghailanders." [48] In the 1920s and 1930s,almost 20,000 White Russians fled the newly established Soviet Union to reside in Shanghai. [49] These Shanghai Russians constituted the second-largest foreign community. By 1932,Shanghai had become the world's fifth largest city and home to 70,000 foreigners. [50] In the 1930s,some 30,000 Jewish refugees from Europe arrived in the city. [51]

- Skyline of Shanghai Pudong at night,September 2021

- Shanghai,filmed in 1937

- The Bund in the late 1920s seen from the French Concession

- Nanking Road (modern-day East Nanjing Road) in the 1930s

- Shanghai Park Hotel was the tallest building in Asia for decades.

- Former Shanghai Library

- The HSBC Building,built in 1923,and the Customs House,built in 1927

Japanese invasion

On 28 January 1932,Japanese forces invaded Shanghai while the Chinese resisted. More than 10,000 shops and hundreds of factories and public buildings [52] were destroyed,leaving Zhabei district ruined. About 18,000 civilians were either killed,injured,or declared missing. [37] A ceasefire was brokered on 5 May. [53] In 1937,the Battle of Shanghai resulted in the occupation of the Chinese-administered parts of Shanghai outside of the International Settlement and the French Concession. People who stayed in the occupied city suffered on a daily basis,experiencing hunger,oppression,or death. [54] The foreign concessions were ultimately occupied by the Japanese on 8 December 1941 and remained occupied until Japan's surrender in 1945;multiple war crimes were committed during that time. [55]

A side-effect of the Japanese invasion of Shanghai was the Shanghai Ghetto. Japanese consul to Kaunas,Lithuania,Chiune Sugihara issued thousands of visas to Jewish refugees who were escaping the Nazi's Final Solution to the Jewish Question. They traveled from Keidan,Lithuania across Russia by railroad to the Vladivostok from where they traveled by ship to Kobe,Japan. Their stay in Kobe was short as the Japanese government transferred them to Shanghai by November 1941. Other Jewish refugees found haven in Shanghai,not through Sugihara,but came on ships from Italy. The refugees from Europe were interned into a cramped ghetto in the Hongkou District,and after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor,even the Iraqi Jews who had been living in Shanghai from before the outbreak of WWII were interned. Among the refugees in the Shanghai Ghetto was the Mirrer Yeshiva,including its students and faculty. On 3 September 1945,the Chinese Army liberated the Ghetto and most of the Jews left over the next few years. [56]

On 27 May 1949,the People's Liberation Army took control of Shanghai through the Shanghai Campaign. Under the new People's Republic of China (PRC),Shanghai was one of only three municipalities not merged into neighboring provinces (the others being Beijing and Tianjin). [57] Most foreign firms moved their offices from Shanghai to Hong Kong,as part of a foreign divestment due to the PRC's victory. [58]

Modernity

After the war,Shanghai's economy was restored—from 1949 to 1952,the city's agricultural and industrial output increased by 51.5% and 94.2%,respectively. [37] There were 20 urban districts and 10 suburbs at the time. [59] On 17 January 1958,Jiading,Baoshan,and Shanghai County in Jiangsu became part of Shanghai Municipality,which expanded to 863 km2 (333.2 sq mi). The following December,the land area of Shanghai was further expanded to 5,910 km2 (2,281.9 sq mi) after more surrounding suburban areas in Jiangsu were added:Chongming,Jinshan,Qingpu,Fengxian,Chuansha,and Nanhui. [60] In 1964,the city's administrative divisions were rearranged to 10 urban districts and 10 counties. [59]

As the industrial center of China with the most skilled industrial workers,Shanghai became a center for radical leftism during the 1950s and 1960s. The radical leftist Jiang Qing and her three allies,together the Gang of Four,were based in the city. [61] During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976),Shanghai's society was severely damaged. The majority of the workers in the Shanghai branch of the People's Bank of China were Red Guards and they formed a group called the Anti-Economy Liaison Headquarters within the branch. [62] : 38 The Anti-Economy Liaison Headquarters dismantled economic organizations in Shanghai,investigated bank withdrawals,and disrupted regular bank service in the city. [62] : 38 The Shanghai People's Commune was established in the city during the January Storm of 1967. Despite the disruptions of the Cultural Revolutions,Shanghai maintained economic production with a positive annual growth rate. [37]

During the Third Front campaign to develop basic industry and heavy industry in China's hinterlands in case of invasion by the Soviet Union or the United States,354,900 Shanghainese were sent to work on Third Front projects. [63] : xvi The centerpiece of Shanghai's Small Third Front project was the "rear base" in Anhui rear base which served as "a multi-function manufacturing base for anti-aircraft and anti-tank weaponry. [63] : xvi

Since 1949,Shanghai has been a comparatively heavy contributor of tax revenue to the central government;in 1983,the city's contribution in tax revenue was greater than investment received in the past 33 years combined. [64] Its importance to the fiscal well-being of the central government also denied it from economic liberalizations begun in 1978.

In 1990,Deng Xiaoping permitted Shanghai to initiate economic reforms,which reintroduced foreign capital to the city and developed the Pudong district,resulting in the birth of Lujiazui. [65] That year,the China's central government designated Shanghai as the "Dragon Head" of economic reform. [66] As of 2020,Shanghai is classified as an Alpha+ city by the Globalization and World Cities Research Network,making it one of the world's Top 10 major cities. [67]

In early 2022,Shanghai experienced a large outbreak of COVID-19 cases. After localized lockdowns failed to stem the rise in cases,the Chinese government locked down the entire city on 5 April. This resulted in widespread food shortages across the city emerged as food-supply chains were severely disrupted by the government's lockdown measures,which was not lifted until 1 June. [68]

Geography

Shanghai is located on the Yangtze Estuary of China's east coast,with the Yangtze River to the north and Hangzhou Bay to the south,with the East China Sea to the east. The land is formed by the Yangtze's natural deposition and modern land reclamation projects. As such,it has sandy soil,and skyscrapers have to be built with deep concrete piles to avoid sinking into the soft ground. [69] The provincial-level Municipality of Shanghai administers both the estuary and many of its surrounding islands. It borders the provinces of Zhejiang to the south and Jiangsu to the west and north. [70] The municipality's northernmost point is on Chongming Island,which is the second-largest island in mainland China after its expansion during the 20th century. [71] It does not administratively include an exclave of Jiangsu on northern Chongming or the two islands forming Shanghai's Yangshan Port,which are parts of Zhejiang's Shengsi County.

Shanghai is located on an alluvial plain. As such,the vast majority of its 6,340.5 km2 (2,448.1 sq mi) land area is flat,with an average elevation of 4 m (13 ft). [8] Tidal flat ecosystems exist around the estuary,however,they have long been reclaimed for agricultural purposes. [72] The city's few hills,such as She Shan,lie to the southwest,and its highest point is the peak of Dajinshan Island (103 m or 338 ft) in Hangzhou Bay. [8] Shanghai has many rivers,canals,streams,and lakes,and it is known for its rich water resources as part of the Lake Tai drainage basin. [73]

| Shanghai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Downtown Shanghai is bisected by the Huangpu River,a man-made tributary of the Yangtze created by order of Lord Chunshen during the Warring States period. [28] The historic center of the city was located on the west bank of the Huangpu (Puxi),near the mouth of Suzhou Creek,connecting it with Lake Tai and the Grand Canal. The central financial district,Lujiazui,has been established on the east bank of the Huangpu (Pudong). Along Shanghai's eastern shore,the destruction of local wetlands due to the construction of Pudong International Airport has been partially offset by the protection and expansion of a nearby shoal,Jiuduansha,as a nature preserve. [74]

Climate

Shanghai has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen:Cfa),with an average annual temperature of 17.5 °C (63.5 °F) for downtown areas and 16.2–17.2 °C (61.2–63.0 °F) for suburbs. [69] The city experiences four distinct seasons. Winters are temperate to cold and damp—northwesterly winds from Siberia can cause nighttime temperatures to drop below freezing. Each year,there are an average of 4.7 days with snowfall and 1.6 days with snow cover. [69] Summers are hot and humid,and occasional downpours or freak thunderstorms can be expected. On average,14.5 days exceed 35 °C (95 °F) annually. In summer and the beginning of autumn,the city is susceptible to typhoons. [75]

The most pleasant seasons are generally spring,although changeable and often rainy,and autumn,which is usually sunny and dry. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 31% in June to 50% in August,the city receives 1,754 hours of bright sunshine annually.(All the mean values mentioned in this paragraph are data observed in Baoshan District)Extremes since 1951 have ranged from −10.1 °C (14 °F) on 31 January 1977 (unofficial record of −12.1 °C (10 °F) was set on 19 January 1893) to 40.9 °C (106 °F) on 13 July 2022 at a weather station in Xujiahui.

| Climate data for Shanghai (Minhang District),1991–2020 normals,extremes 1951–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.1 (71.8) | 27.0 (80.6) | 29.6 (85.3) | 34.3 (93.7) | 36.4 (97.5) | 37.5 (99.5) | 40.9 (105.6) | 39.9 (103.8) | 38.2 (100.8) | 36.0 (96.8) | 28.7 (83.7) | 24.0 (75.2) | 40.9 (105.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) | 10.7 (51.3) | 14.8 (58.6) | 20.6 (69.1) | 25.5 (77.9) | 28.3 (82.9) | 32.8 (91.0) | 32.3 (90.1) | 28.5 (83.3) | 23.6 (74.5) | 17.9 (64.2) | 11.5 (52.7) | 21.3 (70.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.9 (40.8) | 6.6 (43.9) | 10.4 (50.7) | 15.8 (60.4) | 20.9 (69.6) | 24.4 (75.9) | 28.8 (83.8) | 28.5 (83.3) | 24.7 (76.5) | 19.5 (67.1) | 13.7 (56.7) | 7.3 (45.1) | 17.1 (62.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) | 3.3 (37.9) | 6.8 (44.2) | 11.9 (53.4) | 17.2 (63.0) | 21.5 (70.7) | 25.8 (78.4) | 25.7 (78.3) | 21.6 (70.9) | 15.9 (60.6) | 10.1 (50.2) | 3.9 (39.0) | 13.8 (56.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −10.1 (13.8) | −7.9 (17.8) | −5.4 (22.3) | −0.5 (31.1) | 6.9 (44.4) | 12.3 (54.1) | 16.3 (61.3) | 18.8 (65.8) | 10.8 (51.4) | 1.7 (35.1) | −4.2 (24.4) | −8.5 (16.7) | −10.1 (13.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 70.4 (2.77) | 65.4 (2.57) | 95.4 (3.76) | 82.5 (3.25) | 93.2 (3.67) | 207.3 (8.16) | 148.0 (5.83) | 187.1 (7.37) | 118.1 (4.65) | 68.4 (2.69) | 59.4 (2.34) | 50.3 (1.98) | 1,245.5 (49.04) |

| Average precipitation days (≥0.1 mm) | 10.9 | 10.2 | 12.9 | 11.3 | 11.2 | 14.5 | 11.7 | 12.4 | 9.8 | 7.4 | 9.1 | 8.3 | 129.7 |

| Average snowy days | 1.8 | 1.4 | 0.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.7 | 4.4 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74 | 73 | 72 | 71 | 73 | 80 | 78 | 78 | 76 | 73 | 74 | 72 | 75 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 114.8 | 117.9 | 143.8 | 168.1 | 176.8 | 131.2 | 209.4 | 202.3 | 163.7 | 162.1 | 131.1 | 129.7 | 1,850.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 36 | 37 | 39 | 43 | 41 | 31 | 49 | 50 | 45 | 46 | 42 | 41 | 42 |

| Source:China Meteorological Administration [76] [77] | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

The Bund,located by the bank of the Huangpu River,is home to a row of early 20th-century architecture,ranging in style from the neoclassical HSBC Building to the Art Deco Sassoon House (now part of the Peace Hotel). Many areas in the former foreign concessions are also well-preserved,the most notable being the French Concession. [78] Shanghai is also home to many architecturally distinctive and even eccentric buildings,including the Shanghai Museum,the Shanghai Grand Theatre,the Oriental Art Center,and the Oriental Pearl Tower. Despite rampant redevelopment,the Old City still retains some traditional architecture and designs,such as the Yu Garden,an elaborate Jiangnan style garden. [79]

As a result of its construction boom during the 1920s and 1930s,Shanghai has among the most Art Deco buildings in the world. [78] One of the most famous architects working in Shanghai was LászlóHudec,a Hungarian-Slovak who lived in the city between 1918 and 1947. [80] His most notable Art Deco buildings include the Park Hotel,the Grand Cinema,and the Paramount. [81] Other prominent architects who contributed to the Art Deco style are Clement Palmer and Arthur Turner,who together designed the Peace Hotel,the Metropole Hotel,and the Broadway Mansions; [82] and Austrian architect C.H. Gonda,who designed the Capitol Theatre. The Bund has been revitalized several times. The first was in 1986,with a new promenade by the Dutch architect Paulus Snoeren. [83] The second was before the 2010 Expo,which includes restoration of the century-old Waibaidu Bridge and reconfiguration of traffic flow. [84]

One distinctive cultural element is the shikumen (石库门,"stone storage door") residence,typically two- or three-story gray brick houses with the front yard protected by a heavy wooden door in a stylistic stone arch. [85] Each residence is connected and arranged in straight alleys,known as longtang [lower-alpha 7] (弄堂). The house is similar to western-style terrace houses or townhouses,but distinguished by the tall,heavy brick wall and archway in front of each house. [87]

The shikumen is a cultural blend of elements found in Western architecture with traditional Jiangnan Chinese architecture and social behavior. [85] Like almost all traditional Chinese dwellings,it has a courtyard,which reduces outside noise. Vegetation can be grown in the courtyard,and it can also allow for sunlight and ventilation to the rooms. [88]

Some of Shanghai's buildings feature Soviet neoclassical architecture or Stalinist architecture,though the city has fewer such structures than Beijing. These buildings were mostly erected between the founding of the People's Republic in 1949 and the Sino-Soviet Split in the late 1960s. During this time period,large numbers of Soviet experts,including architects,poured into China to aid the country in the construction of a communist state. An example of Soviet neoclassical architecture in Shanghai is the modern-day Shanghai Exhibition Center. [89]

Shanghai—Lujiazui in particular—has numerous skyscrapers,making it the fifth city in the world with the most skyscrapers. [90] Among the most prominent examples are the 421 m (1,381 ft) high Jin Mao Tower,the 492 m (1,614 ft) high Shanghai World Financial Center,and the 632 m (2,073 ft) high Shanghai Tower,which is the tallest building in China and the third tallest in the world. [91] Completed in 2015,the tower takes the form of nine twisted sections stacked atop each other,totaling 128 floors. [92] It is featured in its double-skin facade design,which eliminates the need for either layer to be opaqued for reflectivity as the double-layer structure has already reduced the heat absorption. [93] The futuristic-looking Oriental Pearl Tower,at 468 m (1,535 ft),is located nearby at the northern tip of Lujiazui. [94] Skyscrapers outside of Lujiazui include the White Magnolia Plaza in Hongkou,the Shimao International Plaza in Huangpu,and the Shanghai Wheelock Square in Jing'an.

- The Shanghai Museum

- The Shanghai Exhibition Center,an example of Stalinist architecture

- The Oriental Pearl Tower at night

- Glass facades of two skyscrapers

Politics

Structure

| | | | | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Title | CCP Committee Secretary | SMPC Chairwoman | Mayor | Shanghai CPPCC Chairman |

| Name | Chen Jining | Huang Lixin | Gong Zheng | Hu Wenrong |

| Ancestral home | Lishu,Jilin | Suqian,Jiangsu | Suzhou,Jiangsu | Putian,Fujian |

| Born | February 1964 (age 60) | August 1962 (age 61) | March 1960 (age 64) | July 1964 (age 59) |

| Assumed office | October 2022 [95] | January 2024 [96] | March 2020 [97] | January 2023 [98] |

Like all governing institutions in mainland China,Shanghai has a parallel party-government system, [99] in which the CCP Committee Secretary,officially termed the Chinese Communist Party Shanghai Municipal Committee Secretary,outranks the Mayor. [100] The CCP committee acts as the top policy-formulation body,and is typically composed of 12 members (including the secretary),and has control over the Shanghai Municipal People's Government. [101] [102]

Political power in Shanghai has frequently been a stepping stone to higher positions in the central government. Since Jiang Zemin became the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in June 1989,all former Shanghai party secretaries but one were elevated to the Politburo Standing Committee,the de facto highest decision-making body in China, [99] including Jiang himself (Party General Secretary), [103] Zhu Rongji (Premier), [104] Wu Bangguo (NPC Chairman), [105] Huang Ju (Vice Premier), [106] Xi Jinping (current General Secretary), [107] Yu Zhengsheng (CPPCC Chairman), [108] Han Zheng (Vice Premier and Vice President), [109] and Li Qiang (Premier). Zeng Qinghong,a former deputy party secretary of Shanghai,also rose to the Politburo Standing Committee and became the Vice President and an influential power broker. [110] Li Xi,another former deputy party secretary of Shanghai,has become the Politburo Standing Committee and Secretary of CCDI member in 2022. The only exception is Chen Liangyu,who was fired in 2006 and later convicted of corruption. [111]

Officials with ties to the Shanghai administration collectively form a powerful faction in the central government known as the Shanghai Clique,which has often been viewed to compete against the rival Youth League Faction over personnel appointments and policy decisions. [112] However,Xi Jinping,successor to Hu Jintao as General Secretary and President,was largely an independent leader and took anti-corruption campaigns on both factions. [113]

Administrative divisions

Shanghai is one of the four municipalities under the direct administration of the Central People's Government, [114] and is divided into 16 county-level districts.

| Administrative divisions of Shanghai | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division code [115] | Division | Area (km2) [116] | Total population 2020 [116] | Seat | Postal code | ||

| 310000 | Shanghai | 6,340.50 | 24,870,895 | Huangpu | 200000 | ||

| 310101 | Huangpu | 20.46 | 662,030 | Waitan Subdistrict | 200001 | ||

| 310104 | Xuhui | 54.76 | 1,113,078 | Xujiahui Subdistrict | 200030 | ||

| 310105 | Changning | 38.30 | 693,051 | Jiangsu Road Subdistrict | 200050 | ||

| 310106 | Jing'an | 36.88 | 975,707 | Jiangning Road Subdistrict | 200040 | ||

| 310107 | Putuo | 54.83 | 1,239,800 | Zhenru Town Subdistrict | 200333 | ||

| 310109 | Hongkou | 23.48 | 757,498 | Jiaxing Road Subdistrict | 200080 | ||

| 310110 | Yangpu | 60.73 | 1,242,548 | Pingliang Road Subdistrict | 200082 | ||

| 310112 | Minhang | 370.75 | 2,653,489 | Xinzhuang town | 201100 | ||

| 310113 | Baoshan | 270.99 | 2,235,218 | Youyi Road Subdistrict | 201900 | ||

| 310114 | Jiading | 464.20 | 1,834,258 | Xincheng Road Subdistrict | 201800 | ||

| 310115 | Pudong | 1,210.41 | 5,681,512 | Huamu Subdistrict | 200135 | ||

| 310116 | Jinshan | 586.05 | 822,776 | Shanyang town | 201500 | ||

| 310117 | Songjiang | 605.64 | 1,909,713 | Fangsong Subdistrict | 201600 | ||

| 310118 | Qingpu | 670.14 | 1,271,424 | Xiayang Subdistrict | 201700 | ||

| 310120 | Fengxian | 687.39 | 1,140,872 | Nanqiao town | 201400 | ||

| 310151 | Chongming | 1,185.49 | 637,921 | Chengqiao town | 202100 | ||

| Divisions in Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Pinyin | Shanghainese Romanization | |

| Shanghai Municipality | 上海市 | Shànghǎi Shì | zaon he zy | |

| Huangpu District | 黄浦区 | HuángpǔQū | waon phu chiu | |

| Xuhui District | 徐汇区 | XúhuìQū | zi we chiu | |

| Changning District | 长宁区 | Chángníng Qū | zan nyin chiu | |

| Jing'an District | 静安区 | Jìng'ān Qū | zin oe chiu | |

| Putuo District | 普陀区 | PǔtuóQū | phu du chiu | |

| Hongkou District | 虹口区 | Hóngkǒu Qū | ghon kheu chiu | |

| Yangpu District | 杨浦区 | YángpǔQū | yan phu chiu | |

| Minhang District | 闵行区 | Mǐnháng Qū | min ghaon chiu | |

| Baoshan District | 宝山区 | Bǎoshān Qū | pau sae chiu | |

| Jiading District | 嘉定区 | Jiādìng Qū | ka din chiu | |

| Pudong New Area | 浦东新区 | Pǔdōng Xīnqū | phu ton sin chiu | |

| Jinshan District | 金山区 | Jīnshān Qū | cin se chiu | |

| Songjiang District | 松江区 | Sōngjiāng Qū | son kaon chiu | |

| Qingpu District | 青浦区 | QīngpǔQū | tsin phu chiu | |

| Fengxian District | 奉贤区 | Fèngxián Qū | von yi chiu | |

| Chongming District | 崇明区 | Chóngmíng Qū | dzon min chiu | |

Although every district has its own urban core,the city hall and major administrative units are located in Huangpu District,which also serves as a commercial area,including the famous Nanjing Road. Other major commercial areas include Xintiandi and Huaihai Road [lower-alpha 8] in Huangpu District,and Xujiahui [lower-alpha 9] in Xuhui District. Many universities in Shanghai are located in residential areas in Yangpu District and Putuo District.

Seven of the districts govern Puxi (lit. "The West Bank," or "West of the River Pu"),the older part of urban Shanghai on the west bank of the Huangpu River. These seven districts are collectively referred to as Shanghai Proper (上海市区) or the core city (市中心),which comprise Huangpu,Xuhui,Changning,Jing'an,Putuo,Hongkou,and Yangpu.

Pudong (lit. "The East Bank," or "East of the River Pu"),the newer part of urban and suburban Shanghai on the east bank of the Huangpu River,is governed by Pudong New Area (浦东新区). [lower-alpha 10]

Seven of the districts govern suburbs,satellite towns,and rural areas farther away from the urban core:Baoshan, [lower-alpha 11] Minhang, [lower-alpha 12] Jiading, [lower-alpha 13] Jinshan, [lower-alpha 14] Songjiang, [lower-alpha 15] Qingpu, [lower-alpha 16] and Fengxian. [lower-alpha 17]

Chongming District comprises the islands of Changxing and Hengsha and most—but not all [lower-alpha 18] —of Chongming Island.

The former district of Nanhui was absorbed into Pudong District in 2009. In 2011,Luwan District merged with Huangpu District. As of 2015 [update] ,these county-level divisions are further divided into the following 210 township-level divisions:109 towns,2 townships,and 99 subdistricts. Those are in turn divided into the following village-level divisions:3,661 neighborhood committees and 1,704 village committees. [120]

There is a sizable Korean community of Shanghai and Japanese community of Shanghai largely in the Minhang District.

Economy

| City | Area km2 | Population (2020) | GDP (CN¥) [14] | GDP (US$) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shanghai | 6,341 | 26,875,500 | CN¥4,465 billion | US$ 663.9 billion |

| Suzhou | 8,488 | 12,748,252 | CN¥2,396 billion | US$ 356.0 billion |

| Ningbo | 9,816 | 9,618,000 | CN¥1,570 billion | US$ 233.5 billion |

| Wuxi | 4,628 | 7,462,135 | CN¥1,485 billion | US$ 221.0 billion |

| Nantong | 8,544 | 7,726,635 | CN¥1,138 billion | US$ 169.2 billion |

| Changzhou | 4,385 | 5,278,121 | CN¥955 billion | US$ 142.0 billion |

| Jiaxing | 4,009 | 5,400,868 | CN¥551 billion | US$ 73.6 billion |

| Huzhou | 5,818 | 3,367,579 | CN¥272 billion | US$ 40.7 billion |

| Zhoushan | 1,378 | 1,157,817 | CN¥151 billion | US$ 20.0 billion |

| Greater Shanghai Metropolitan Area | 53,407 | 79,634,907 | CN¥12.983 trillion | US$1.927 trillion |

Shanghai has been described as the "showpiece" of the booming economy of China. [123] [124] The city is a global center for finance and innovation, [125] [126] and a national center for commerce,trade,and transportation, [127] with the world's busiest container port—the Port of Shanghai. [128] As of 2018,the Greater Shanghai metropolitan area,which includes Suzhou,Wuxi,Nantong,Ningbo,Jiaxing,Zhoushan,and Huzhou,was estimated to produce a gross metropolitan product of nearly 9.1 trillion RMB ($1.33 trillion in nominal or $2.08 trillion in PPP),exceeding that of Mexico with GDP (nominal) of $1.22 trillion,the 15th largest in the world. [129] [130] As of 2020,the economy of Shanghai was estimated to be $1 trillion (PPP),ranking the most productive metro area of China and among the top ten largest metropolitan economies in the world. [131] Shanghai's six largest industries—retail,finance,IT,real estate,machine manufacturing,and automotive manufacturing—comprise about half the city's GDP. [132] As of 2022 [update] ,Shanghai had a GDP of CN¥ 4.46 trillion ($663.87 billion in nominal) that makes up 3.69% of China's GDP,and a GDP per capita of CN¥179,907 (US$26,747 in nominal or US$44,576 in PPP) [11] In 2022,the average annual disposable income of Shanghai's residents was CN¥79,610 (US$11,836) per capita,while the average annual salary of people employed in urban units in Shanghai was CN¥212,476 (US$31,589), [11] making it one of the wealthiest cities in China, [133] but also the most expensive city in mainland China to live in according to a 2023 study by the Economist Intelligence Unit. [134] Since 2018,Shanghai has been hosting the China International Import Expo (CIIE) annually,the world's first import-themed national-level expo.

In 2021,Shanghai was the most expensive city in the world. [135] Shanghai was the 5th wealthiest city in the world,with a total wealth amounts to $1.8 trillion, [136] and Shanghai was ranked fifth-highest in the number of billionaires by Forbes. [137] Shanghai's nominal GDP was projected to reach US$1.3 trillion in 2035 (ranking first in China),making it one of the world's Top 5 major cities in terms of GRP according to a study by Oxford Economics. [138] As of August 2023,Shanghai ranked 5th in the world and 2nd in China (after Beijing) by the largest number of the Fortune Global 500 companies in the world. [139]

| Year | 1978 | 1980 | 1983 | 1986 | 1990 | 1993 | 1996 | 2000 | 2003 | 2006 | 2010 | 2013 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 [140] | 2019 [141] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP (¥T) [142] | 0.027 | 0.031 | 0.035 | 0.049 | 0.078 | 0.152 | 0.298 | 0.481 | 0.676 | 1.072 | 1.744 | 2.226 | 2.818 | 3.063 | 3.268 | 3.816 |

| GDP per capita (¥K) [142] | 2.85 | 2.73 | 2.95 | 3.96 | 5.91 | 11.06 | 20.81 | 30.31 | 38.88 | 55.62 | 77.28 | 92.85 | 116.58 | 126.63 | 134.83 | 157.14 |

| Average disposable income (urban) (¥K) [143] [144] [145] | 0.64 | 2.18 | 4.28 | 8.16 | 11.72 | 14.87 | 20.67 | 31.84 | 43.85 | 57.69 | 62.60 | 64.18 (total) | 69.44 (total) | |||

| Average disposable income (rural) (¥K) [146] [144] | 0.40 | 1.67 | 4.85 | 5.57 | 6.66 | 9.21 | 13.75 | 19.21 | 25.52 | 27.82 |

Shanghai was the largest and most prosperous city in East Asia during the 1930s,and its rapid redevelopment began in the 1990s. [47] In the last two decades,Shanghai has been one of the fastest-developing cities in the world;it has recorded double-digit GDP growth in almost every year between 1992 and 2008,before the 2007–2008 financial crisis. [147]

Finance

Shanghai is a global financial center,ranking first in the whole of Asia &Oceania region and third globally (after New York and London) in the 28th edition of the Global Financial Centres Index, [148] published in September 2020 by Z/Yen and China Development Institute. [149] Shanghai is also a large hub of the Chinese and global technology industry and home to a large startup ecosystem. As of 2021,the city was ranked as the 2nd Fintech powerhouse in the world after New York City. [150]

As of 2019 [update] ,the Shanghai Stock Exchange had a market capitalization of US$4.02 trillion,making it the largest stock exchange in China and the fourth-largest stock exchange in the world. [151] In 2009,the trading volume of six key commodities—including rubber,copper,and zinc—on the Shanghai Futures Exchange all ranked first globally. [152] By the end of 2017,Shanghai had 1,491 financial institutions,of which 251 were foreign-invested. [153]

In September 2013 with the backing of Chinese Premier Li Keqiang,the city launched the Shanghai Free-Trade Zone—the first free-trade zone in mainland China. The zone introduced a number of pilot reforms designed to incentivize foreign investment. In April 2014, The Banker reported that Shanghai "has attracted the highest volumes of financial sector foreign direct investment in the Asia-Pacific region in the 12 months to the end of January 2014." [154] In August 2014, fDi magazine named Shanghai the "Chinese Province of the Future 2014/15" due to "particularly impressive performances in the Business Friendliness and Connectivity categories,as well as placing second in the Economic Potential and Human Capital and Lifestyle categories." [155]

Manufacturing

As one of the main industrial centers of China,Shanghai plays a key role in domestic manufacturing and heavy industry. Several industrial zones—including Shanghai Hongqiao Economic and Technological Development Zone,Jinqiao Export Economic Processing Zone,Minhang Economic and Technological Development Zone,and Shanghai Caohejing High-Tech Development Zone—are backbones of Shanghai's secondary sector. Shanghai is home to China's largest steelmaker Baosteel Group,China's largest shipbuilding base Hudong–Zhonghua Shipbuilding Group,and one of China's oldest shipbuilders,the Jiangnan Shipyard. [156] [157] Auto manufacturing is another important industry. The Shanghai-based SAIC Motor is one of the three largest automotive corporations in China,and has strategic partnerships with Volkswagen and General Motors. [158]

Tourism

Tourism is a major industry of Shanghai. In 2017,the number of domestic tourists increased by 7.5% to 318 million,while the number of overseas tourists increased by 2.2% to 8.73 million. [153] In 2017,Shanghai was the highest earning tourist city in the world. [159] As of 2022 [update] ,Shanghai had 61 five-star hotels,55 four star hotels,1,885 travel agencies,134 rated tourist attractions,and 34 red tourist attractions. [141]

The conference and meeting sector is also growing. According to the International Congress and Convention Association,Shanghai hosted 82 international meetings in 2018,a 34% increase from 61 in 2017. [160] [161]

Free-trade zone

Shanghai is home to China (Shanghai) Pilot Free-Trade Zone,the first free-trade zone in mainland China. [162] As of October 2019 [update] ,it is also the second largest free-trade zone in mainland China in terms of land area (behind Hainan Free Trade Zone ,which covers the whole Hainan province [163] ) by covering an area of 240.22 km2 (92.75 sq mi) and integrating four existing bonded zones—Waigaoqiao Free Trade Zone,Waigaoqiao Free Trade Logistics Park,Yangshan Free Trade Port Area,and Pudong Airport Comprehensive Free Trade Zone. [164] [165] The industrial chain of port logistics has shaped the future development direction of the free-trade zone in Shanghai. Currently,two port chain centers have been approved for construction in Waigaoqiao and Yangshan. [166] Several preferential policies have been implemented to attract foreign investment in various industries to the zone. Because the zone is not technically considered Chinese territory for tax purposes,commodities entering the zone are exempt from duty and customs clearance. [167]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1953 | 5,258,210 | — |

| 1964 | 6,423,017 | +22.2% |

| 1982 | 6,320,829 | −1.6% |

| 1990 | 8,348,299 | +32.1% |

| 2000 | 14,489,919 | +73.6% |

| 2010 | 20,555,098 | +41.9% |

| 2020 | 22,209,380 | +8.0% |

| Source:Census in China [168] | ||

As of 2023 [update] ,Shanghai had a total population of 24,874,500,including 14,801,700 (59.5%) hukou holders (registered locally). [141] As of 2022 [update] ,89.3% of Shanghai's population live in urban areas,and 10.7% live in rural areas. [11] Based on the population of its total administrative area,Shanghai is the second largest of the four municipalities of China,behind Chongqing,but is generally considered the largest Chinese city because the urban population of Chongqing is much smaller. [169] According to the OECD,Shanghai's metropolitan area has an estimated population of 34 million. [170]

According to the Shanghai Municipal Statistics Bureau,about 157,900 residents in Shanghai are foreigners,including 28,900 Japanese,21,900 Americans and 20,800 Koreans. [171] The actual number of foreign citizens in the city is probably much higher. [172] Shanghai is also a domestic immigration city—40.3% (9.8 million) of the city's residents are from other regions of China. [141]

Shanghai has a life expectancy of 83.18 years for the city's registered population, [173] the highest life expectancy of all cities in mainland China. This has also caused the city to experience population aging—in 2021,17.4% (4.3 million) of the city's registered population was aged 65 or above. [141] In 2017,the Chinese government implemented population controls for Shanghai,resulting in a population decline of 10,000 people by the end of the year. [174]

Religion

Due to its cosmopolitan history,Shanghai has a blend of religious heritage;religious buildings and institutions are scattered around the city. According to a 2012 survey,only 13.1% of the city's population belongs to organized religions,including Buddhists with 10.4%,Protestants with 1.9%,Catholics with 0.7%,and other faiths with 0.1% while the remaining 86.9% of the population could be either atheists or involved in worship of nature deities and ancestors or folk religious sects. [175]

Religion in Shanghai (2012):

Buddhism, in its Chinese varieties, has had a presence in Shanghai since the Three Kingdoms period, during which the Longhua Temple—the largest temple in Shanghai—and the Jing'an Temple were founded. [176] Another significant temple is the Jade Buddha Temple, which was named after a large statue of Buddha carved out of jade in the temple. [177] As of 2014 [update] , Buddhism in Shanghai had 114 temples, 1,182 clergical staff, and 453,300 registered followers. [176] The religion also has its own college, the Shanghai Buddhist College , and its own press, Shanghai Buddhological Press . [178]

Catholicism was brought into Shanghai in 1608 by Italian missionary Lazzaro Cattaneo. [179] The Apostolic Vicariate of Shanghai was erected in 1933, and was further elevated to the Diocese of Shanghai in 1946. [180] Notable Catholic sites include the St. Ignatius Cathedral in Xujiahui—the largest Catholic church in the city, [181] the St. Francis Xavier Church, and the She Shan Basilica. [182] Other forms of Christianity in Shanghai include Eastern Orthodox minorities and, since 1996, registered Christian Protestant churches. The Protestant All Saints Church in Huangpu was built in 1925 and features a Neo-Romanesque tower.

Although currently making up a fraction of the religious population in Shanghai, Jewish people have played an influential role in the city's history. After the Treaty of Nanking ended the First Opium War in 1842, the city was opened up to western populations and merchants traveled to Shanghai for its rich business potential, including many prominent Jewish families. The Sassoons amassed great wealth in the opium and textile trades, cementing their status by funding many of the buildings that have become iconic in Shanghai's skyline, such as the Cathay Hotel in 1929. [183] The Hardoons were another prominent Baghdadi Jewish family that used their business success to define Shanghai in the 20th century. The head of the family, Silas Hardoon, one of the richest people in the world during the 1800s, financed Nanjing Road, which then housed departmental stores in the International Settlement, that is now one of the busiest shopping centers in the world. [183]

During World War II, thousands of Jews emigrated to Shanghai in an effort to flee Nazi Germany. They lived in a designated area called the Shanghai Ghetto and formed a community centered on the Ohel Moishe Synagogue, which is now the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum. [184] In 1939, Horace Kadoorie, the head of the powerful philanthropic Sephardic Jewish family in Shanghai, founded the Shanghai Jewish Youth Association to support Jewish refugees through English education so they would be prepared to emigrate from Shanghai when the time came. [185]

Islam came into Shanghai during the Yuan dynasty. The city's first mosque, Songjiang Mosque, was built during the Zhizheng (至正) era under Emperor Huizong (reigned 1333 – 1368). Shanghai's Muslim population increased in the 19th and early 20th centuries (when the city was a treaty port), during which time many mosques—including the Xiaotaoyuan Mosque, the Huxi Mosque, and the Pudong Mosque—were built. The Shanghai Islamic Association is located in the Xiaotaoyuan Mosque in Huangpu. [186]

Shanghai has several folk religious temples, including the City God Temple at the heart of the Old City, the Dajing Ge Pavilion dedicated to the Three Kingdoms general Guan Yu, the Confucian Temple of Shanghai, and a major Taoist center Shanghai White Cloud Temple where the Shanghai Taoist Association locates. [187]

Language

The vernacular language spoken in the city is Shanghainese, part of the Taihu Wu subgroup of the Wu Chinese language family. This is different from the national language, Mandarin, which is mutually unintelligible with Wu Chinese. [189] Modern Shanghainese derives from the indigenous Wu spoken in the former Songjiang prefecture but has been influenced by other dialects of Taihu Wu, most notably Suzhounese, and Ningbonese [190]

Prior to its expansion, the language spoken in Shanghai was not as prominent as those spoken around Jiaxing and later Suzhou, [190] and was known as "the local tongue" (本地閑話), a name which is now used in suburbs only. [191] In the late 19th century, downtown Shanghainese (市區閑話 or simply 上海閑話) appeared, undergoing rapid changes and quickly replacing Suzhounese as the prestige dialect of the Yangtze River Delta region. At the time, most of the immigration into the city came from the two adjacent provinces, Jiangsu and Zhejiang, the local dialects of which had the greatest influence on Shanghainese. After 1949, Putonghua (Standard Mandarin) has also had a great impact on Shanghainese as a result of being rigorously promoted by the government. [190] Since the 1990s, many migrants outside of the Wu-speaking region have come to Shanghai for education and jobs. They often cannot speak the local language and therefore use Putonghua (Mandarin) as a lingua franca. Because Putonghua and English were more favored, Shanghainese began to decline, and fluency among young speakers weakened. In recent years, there have been movements within the city to promote the local language and protect it from fading out. [192] [193]

Education and research

Shanghai is an international center of research and development and as of 2022, it was ranked third globally and second in the whole Asia & Oceania region (after Beijing) by scientific research outputs, as tracked by the Nature Index. [194] It is also a major center of higher education in China. As of 2023, Shanghai had 68 universities and colleges, ranking first in East China region as a city with most higher education institutions. [195]

Shanghai has many highly ranked educational institutions, [196] [197] with 15 universities listed in 147 Double First-Class Universities ranking second nationwide among all cities in China (after Beijing). A number of China's most prestigious universities appearing in the global university rankings are based in Shanghai, including Fudan University, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Tongji University, East China Normal University, Shanghai University, East China University of Science and Technology, Donghua University, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, ShanghaiTech University, Shanghai International Studies University, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai University of Electric Power, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai Maritime University, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai University of Engineering Science, Shanghai Institute of Technology, Shanghai Conservatory of Music, and Shanghai University of Sport. [197] [198] [199] Some of these universities were selected as "985 universities" or "211 universities" since the 90s by the Chinese government in order to build world-class universities. [200] [201]

Shanghai is a seat of two members (Fudan University and Shanghai Jiao Tong University) of the C9 League, an alliance of elite Chinese universities offering comprehensive and leading education, [202] and these two universities are ranked consistently in the Asia top 10, [203] [204] and in the global top 100 research comprehensive universities according to the most influential university rankings in the world such as QS Rankings, Shanghai Rankings, Times Higher Education Rankings and U.S. News & World Report Best Global Universities Ranking. [205] [206] [207] [197] Fudan University established a joint EMBA program with Washington University in St. Louis in 2002 which has since consistently been ranked as one of the best in the world. [208] [209]

The other two members of the "Project 985," Tongji University and East China Normal University, are also based in Shanghai and internationally; they are regarded as one of the most reputable Chinese universities by the Times Higher Education World Reputation Rankings where they ranked 150–175th globally. [210] The city is also home to the Shanghai University of Sport, which consistently ranks the best in China among universities specialized in sports. [211] As of 2023, Shanghai University of Sport ranks #1 in Asia and #36 globally according to the "Global Ranking of Sport Science Schools and Departments 2023" released by Shanghai Ranking. [212]

The city has many Chinese–foreign joint education institutes , such as the Shanghai University–University of Technology Sydney Business School since 1994, the University of Michigan–Shanghai Jiao Tong University Joint Institute since 2006, and New York University Shanghai—the first China–U.S. joint venture university—since 2012. [213] [214] In 2013, the Shanghai Municipality and the Chinese Academy of Sciences founded the ShanghaiTech University in the Zhangjiang Hi-Tech Park in Pudong. [215] Shanghai is also home to the cadre school China Executive Leadership Academy in Pudong and the China Europe International Business School. The city government's education agency is the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission.

The city is also a seat of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences, China's oldest think tank for the humanities and social sciences. It is the largest one outside the capital of Beijing after the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). [216]

By the end of 2023, the city also had a total of 49 institutions for postgraduate education, 68 institutions for higher education, 900 secondary schools, 70 vocational schools, 664 primary schools, and 31 special education schools. [141] In Shanghai, the nine years of compulsory education—including five years of primary education and four years of junior secondary education—are free, with a gross enrollment ratio of over 99.9%. [141] The city's compulsory education system is among the best in the world: in 2009 and 2012, 15-year-old students from Shanghai ranked first in every subject (math, reading, and science) in the Program for International Student Assessment, a worldwide study of academic performance conducted by the OECD. [217] [218] The consecutive three-year senior secondary education is priced and uses the Senior High School Entrance Examination (Zhongkao) as a selection process, with a gross enrollment ratio of 98%. [219] Among all senior high schools, the four with the best teaching quality—Shanghai High School, No. 2 High School Attached to East China Normal University, High School Affiliated to Fudan University, and High School Affiliated to Shanghai Jiao Tong University—are termed "The Four Schools" (“四校”) of Shanghai. [220] As of October 2019 [update] , the city's National College Entrance Examination (Gaokao) is structured under the "3+3" system, in which all general senior high school students study three compulsory subjects (Chinese, English, and math) and three subjects chosen from six options (physics, chemistry, biology, history, geography, and politics). [221]

Transport

Public

Shanghai has an extensive public transportation system comprising metros, buses, ferries, and taxis, all of which can be accessed using a Shanghai Public Transport Card. [222]

Shanghai's rapid transit system, the Shanghai Metro, incorporates both subway and light metro lines and extends to every core urban district as well as neighboring suburban districts. As of 2021 [update] , there are 19 metro lines (excluding the Shanghai maglev train and Jinshan railway), 515 stations, and 803 km (499 mi) of lines in operation, making it the longest network in the world. [141] On 8 March 2019, it set the city's daily metro ridership record with 13.3 million. [223] The average fare ranges from CN¥3 (US$0.48) to CN¥9 (US$1.28), depending on the travel distance. [224]

Opened in 2004, the Shanghai maglev train is the first and the fastest commercial high-speed maglev in the world, with a maximum operation speed of 430 km/h (267 mph). [225] The train can complete the 30-kilometer (19 mi) journey between Longyang Road station and Pudong International Airport in 7 minutes 20 seconds, [226] comparing to 32 minutes by Metro Line 2 [227] and 30 minutes by car. [228] A one-way ticket costs CN¥50 (US$8), or CN¥40 (US$6.40) for those with airline tickets or public transportation cards. A round-trip ticket costs CN¥80 (US$12.80), and VIP tickets cost double the standard fare. [229]

With the first tram line been in service in 1908, trams were once popular in Shanghai in the early 20th century. By 1925, there were 328 tramcars and 14 routes operated by Chinese, French, and British companies collaboratively, [230] all of which were nationalized after the PRC's victory in 1949. Since the 1960s, many tram lines were either dismantled or replaced by trolleybus or motorbus lines; [231] the last tram line was demolished in 1975. [232] Shanghai reintroduced trams in 2010, as a modern rubber-tire Translohr system in Zhangjiang area of East Shanghai as Zhangjiang Tram. [233] In 2018, the steel wheeled Songjiang Tram started operating in Songjiang District. [234] Additional tram lines are under planning in Hongqiao Subdistrict and Jiading District as of 2019 [update] . [235]

Shanghai also has the world's most extensive bus network, including the world's oldest continuously operating trolleybus system, with 1,575 lines covering a total length of 8,997 km (5,590 mi) by 2019. [141] The system is operated by multiple companies. [236] Bus fares generally cost CN¥2 (US$0.32). [237] Shanghai also has three bus rapid transit systems, namely the Yan'an Road Medium Capacity Bus Transit System, Fengpu Express and Nantuan Express.

As of 2019 [update] , a total of 40,000 taxis were in operation in Shanghai. [141] The base fare for taxis is CN¥14 (US$2.24), which covers the first 3 km (2 mi) and includes a CN¥1 (US$0.14) fuel surcharge. The base fare is CN¥18 (US$2.55) between 11:00 pm and 5:00 am. Each additional kilometer costs CN¥2.7 (US$0.45), or CN¥4.05 (US$0.67) between 11:00 pm and 5:00 am. [238] Taxicabs and DiDi play major roles in urban transportation and DiDi is often cheaper than taxis. [239]

As of January 2021, Shanghai Metro has 459 stations and 772 km. The scale of operation is the first in the world. in 2017, the average daily passenger traffic of the Shanghai metro was 9.693 million, and the total passenger traffic reached 3.538 billion. It is one of the busiest metro cities in the world. The metro lines cover the central city densely and connect most districts and counties. [240]

Roads and expressways

Shanghai is a major hub of China's expressway network. Many national expressways (prefixed with the letter G) pass through or end in Shanghai, including Jinghu Expressway (overlaps with Hurong Expressway), Shenhai Expressway, Hushaan Expressway, Huyu Expressway, Hukun Expressway (overlaps with Hangzhou Bay Ring Expressway), and Shanghai Ring Expressway. [241] There are also numerous municipal expressways prefixed with the letter S. [241] As of 2019, Shanghai has a total of 12 bridges and 14 tunnels crossing the Huangpu River. [242] [243] The Shanghai Yangtze River Bridge is the city's only bridge–tunnel complex across Yangtze River.

The expressway network within the city center consists of North–South Elevated Road, Yan'an Elevated Road, and Inner Ring Road. Other ring roads in Shanghai include Middle Ring Road, Outer Ring Expressway, and Shanghai Ring Expressway.

Bicycle lanes are common in Shanghai, separating non-motorized traffic from car traffic on most surface streets. However, on some main roads, including all expressways, bicycles and motorcycles are banned. In recent years, cycling has seen a resurgence in popularity due to the emergence of a large number of dockless app-based bicycle-sharing systems, such as Mobike, Bluegogo, and ofo. [244] As of December 2018 [update] , bicycle-sharing systems had an average of 1.15 million daily riders within the city. [245]

Private car ownership in Shanghai is rapidly increasing: in 2019, there were 3.40 million private cars in the city, a 12.5% increase from 2018. [141] New private cars cannot be driven without a license plate, which are sold in monthly license plate auctions. Around 9,500 license plates are auctioned each month, and the average price is about CN¥89,600 (US$12,739) in 2019. [246] According to the city's vehicle regulations introduced in June 2016, only locally registered residents and those who have paid social insurance or individual income taxes for over three years are eligible to be in the auction. The purpose of this policy is to limit the growth of automobile traffic and alleviate congestion. [247] Public transport, biking infrastructure, walkability, generally permits to live in the city without a car. [248] [249] [250]

License plates for fully electric cars or plug-in hybrid vehicles are free. [251] : 168

Railways

Shanghai has four major railway stations: Shanghai railway station, Shanghai South railway station, Shanghai West railway station, and Shanghai Hongqiao railway station. [252] All are connected to the metro network and serve as hubs in the railway network of China. And now Shanghai has around twenty railway lines running under this city, which largely facilitate people's life in Shanghai.

Built in 1876, the Woosung railway was the first railway in Shanghai and the first railway in operation in China [253] By 1909, Shanghai–Nanjing railway and Shanghai–Hangzhou railway were in service. [254] [255] As of October 2019 [update] , the two railways have been integrated into two main railways in China: Beijing–Shanghai railway and Shanghai–Kunming railway, respectively. [256]

Shanghai has four high-speed railways (HSRs): Beijing–Shanghai HSR (overlaps with Shanghai–Wuhan–Chengdu passenger railway), Shanghai–Nanjing intercity railway, Shanghai–Kunming HSR, and Shanghai–Nantong railway. One HSR is under construction: Shanghai–Suzhou–Huzhou HSR. [257] [258]

Shanghai also has four commuter railways: Pudong railway (passenger service is currently suspended) and Jinshan railway operated by China Railway, and Line 16 and Line 17 operated by Shanghai Metro. [259] [260] As of January 2022 [update] , four additional lines—Chongming line, Jiamin line, Airport link line and Lianggang Express line—are under construction. [260] [261]

Air and sea

Shanghai is one of the largest air transportation hubs in Asia. [262] The city has two commercial airports: Shanghai Pudong International Airport and Shanghai Hongqiao International Airport. [263] Pudong International Airport is the primary international airport, while Hongqiao International Airport mainly operates domestic flights with limited short-haul international flights. In 2018, Pudong International Airport served 74.0 million passengers and handled 3.8 million tons of cargo, making it the ninth-busiest airport by passenger volume and third-busiest airport by cargo volume. [264] [265] The same year, Hongqiao International Airport served 43.6 million passengers, making it the 19th-busiest airport by passenger volume. [264]

Since its opening, the Port of Shanghai has rapidly grown to become the largest port in China. [266] Yangshan Port was built in 2005 because the river was unsuitable for docking large container ships. The port is connected with the mainland through the 32-kilometer (20 mi) long Donghai Bridge. Although the port is run by the Shanghai International Port Group under the government of Shanghai, it administratively belongs to Shengsi County, Zhejiang. [267]

Overtaking the Port of Singapore in 2010, [268] the Port of Shanghai has become world's busiest container port with an annual TEU transportation of 42 million in 2018. [269] Besides cargo, the Port of Shanghai handled 259 cruises and 1.89 million passengers in 2019. [141]

Shanghai is part of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road that runs from the Chinese coast to the south via the southern tip of India to Mombasa, from there to the Mediterranean, there to the Upper Adriatic region to the northern Italian hub of Trieste with its rail connections to Central and the Eastern Europe. [270] [271] [272] [273] [274]

Culture

The culture of Shanghai was formed by a combination of the nearby Wuyue culture and the "East Meets West" Haipai culture. Wuyue culture's influence is manifested in Shanghainese language—which comprises dialectal elements from nearby Jiaxing, Suzhou, and Ningbo—and Shanghai cuisine, which was influenced by Jiangsu cuisine and Zhejiang cuisine. [275] Haipai culture emerged after Shanghai became a prosperous port in the early 20th century, with numerous foreigners from Europe, America, Japan, and India moving into the city. [276] The culture fuses elements of Western cultures with the local Wuyue culture, and its influence extends to the city's literature, fashion, architecture, music, and cuisine. [277] The term Haipai—originally referring to a painting school in Shanghai—was coined by a group of Beijing writers in 1920 to criticize some Shanghai scholars for admiring capitalism and Western culture. [277] [278] In the early 21st century, Shanghai has been recognized as a new influence and inspiration for cyberpunk culture. [279]

Museums

Cultural curation in Shanghai has seen significant growth since 2013, with several new museums having been opened in the city. [280] This is in part due to the city's 2018 development plans, which aim to make Shanghai "an excellent global city." [281] As such, Shanghai has several museums of regional and national importance. [282] [283] The Shanghai Museum has one of the largest collections of Chinese artifacts in the world, including a large collection of ancient Chinese bronzes and ceramics. [284] The China Art Museum, located in the former China pavilion at Expo 2010, is one of the largest museums in Asia and displays an animated replica of the 12th century painting Along the River During the Qingming Festival. [285] The Shanghai Natural History Museum and the Shanghai Science and Technology Museum are notable natural history and science museums. In addition, there are numerous smaller, specialist museums housed in important archeological and historical sites, such as the Songze Museum, [286] the Site of the First National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, the site of the former Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea, [287] the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum, and the Shanghai Post Office Museum (located in the General Post Office Building). [288]

Cuisine

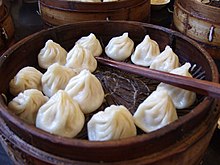

Benbang cuisine (本帮菜) [289] is cooking style that originated in the 1600s, with influences from surrounding provinces. It emphasizes the use of condiments while retaining the original flavors of the raw ingredients. Sugar is an important ingredient in Benbang cuisine, especially when used in combination with soy sauce. Signature dishes of Benbang cuisine include Xiaolongbao, Red braised pork belly, and Shanghai hairy crab. [290] Haipai cuisine, on the other hand, is a Western-influenced cooking style that originated in Shanghai. It absorbed elements from French, British, Russian, German, and Italian cuisines and adapted them to suit the local taste according to the features of local ingredients. [291] Famous dishes of Haipai cuisine include Shanghai-style borscht (罗宋汤, "Russian soup"), crispy pork cutlets, and Shanghai salad derived from Olivier salad. [292] Both Benbang and Haipai cuisine make use of a variety of seafood, including freshwater fish, shrimps, and crabs. [293]

Arts

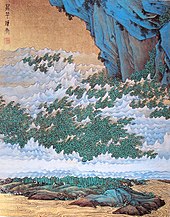

The Songjiang School (淞江派), containing the Huating School (华亭派) founded by Gu Zhengyi, [294] was a small painting school in Shanghai during the Ming and Qing Dynasties. [295] It was represented by Dong Qichang. [296] The school was considered an expansion of the Wu School in Suzhou, the cultural center of the Jiangnan region at the time. [297] In the mid 19th century, the Shanghai School movement commenced, focusing less on the symbolism emphasized by the Literati style but more on the visual content of painting through the use of bright colors. Secular objects like flowers and birds were often selected as themes. [298] Western art was introduced to Shanghai in 1847 by Spanish missionary Joannes Ferrer (范廷佐), and the city's first Western atelier was established in 1864 inside the Tushanwan orphanage . [299] During the Republic of China, many famous artists including Zhang Daqian, Liu Haisu, Xu Beihong, Feng Zikai, and Yan Wenliang settled in Shanghai, allowing it to gradually become the art center of China. Various art forms—including photography, wood carving, sculpture, comics (Manhua), and Lianhuanhua—thrived. Sanmao was created to dramatize the chaos created by the Second Sino-Japanese War. [300] Today, the most comprehensive art and cultural facility in Shanghai is the China Art Museum. In addition, the Chinese Painting Academy features traditional Chinese painting, [301] while the Power Station of Art displays contemporary art. [302] The city also has many art galleries, many of which are located in the M50 Art District and Tianzifang. First held in 1996, the Shanghai Biennale has become an important place for Chinese and foreign arts to interact. [303]

Traditional Chinese opera (Xiqu) became a popular source of public entertainment in the late 19th century. In the early 20th century, monologue and burlesque in Shanghainese appeared, absorbing elements from traditional dramas. The Great World opened in 1912 and was a significant stage at the time. [304] In the 1920s, Pingtan expanded from Suzhou to Shanghai. [305] Pingtan art developed rapidly to 103 programs every day by the 1930s because of the abundant commercial radio stations in the city. Around the same time, a Shanghai-style Beijing Opera was formed. Led by Zhou Xinfang and Gai Jiaotian , it attracted many Xiqu masters, like Mei Lanfang, to the city. [306] A small troupe from Shengxian (now Shengzhou) also began to promote Yue opera on the Shanghainese stage. [307] A unique style of opera, Shanghai opera, was formed when local folksongs were fused with modern operas. [308] As of 2012, prominent troupes in Shanghai include Shanghai Jingju Theatre Company, Shanghai Kunqu Opera Troupe , Shanghai Yue Opera House, and Shanghai Huju Opera House. [309]

Drama appeared in missionary schools in Shanghai in the late 19th century. At the time, it was mainly performed in English. Scandals in Officialdom (官场丑史), staged in 1899, was one of the earliest-recorded plays. [310] In 1907, Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly (黑奴吁天录) was performed at the Lyceum Theatre . [311] After the New Culture Movement, drama became a popular way for students and intellectuals to express their views. The city has several major institutes of theater training, including the Shanghai Conservatory of Music, the Shanghai Dramatic Arts Centre, the Shanghai Opera House, and the Shanghai Theatre Academy. Notable theaters in Shanghai include the Shanghai Grand Theatre, the Oriental Art Center, and the People's Theatre.