Music Distribution

We are currently experiencing some short-term hiccups with our physical CD distribution: in the meantime please click on the album links on our Albums page and hit the Amazon buying links to check if your title is available .

Download sales continue to be available via the usual services and you can also still stream our music as usual.

Music Distribution

We are currently experiencing some short-term hiccups with our physical CD distribution: in the meantime please click on the album links on our Albums page and hit the Amazon buying links to check if your title is available .

Download sales continue to be available via the usual services and you can also still stream our music as usual.

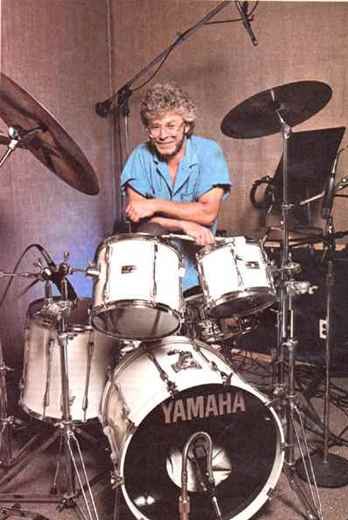

Allan Schwartzberg: The Working Drummer

His two musician-friends in the back of the car who are hitching a ride analyze the situation and advise the latter. Schwartzberg nods in agreement and adroitly maneuvers his Mercedes from Sixth Avenue’s far right lane over into its far left lane like a cool and seasoned cabbie. Quickly he turns down a Manhattan sidestreet and escapes the traffic snarl behind us.

It turns out to have been a smart move. Eighth Avenue is certainly less congested, so we make it up to midtown in pretty good time. The two musicians in the backseat are dropped off at their studio minutes before their next session. Schwartzberg, however, won’t fare as well. He knows he’ll be a few minutes late for his next session, thanks to another traffic tie-up;. This time it’s on the street where he normally parks.

“What happens when a session player is late for a session?” I wonder out loud. Schwartzberg shakes his head. “These days, you gotta really try to be on time for every session,” he says, as we finally get to the parking garage. Schwartzberg pulls in, screeches to a stop, and gives the car keys to the attendant. I help him lift his gear out of the car. Together we lug it a half block to the recording studio. “When you’re late, you hope that you can come up with an amusing excuse,” he says. “Last week, I told a producer ‘I’m sorry to be late but I’m still not as late as your checks!'”

“What happens when a session player is late for a session?” I wonder out loud. Schwartzberg shakes his head. “These days, you gotta really try to be on time for every session,” he says, as we finally get to the parking garage. Schwartzberg pulls in, screeches to a stop, and gives the car keys to the attendant. I help him lift his gear out of the car. Together we lug it a half block to the recording studio. “When you’re late, you hope that you can come up with an amusing excuse,” he says. “Last week, I told a producer ‘I’m sorry to be late but I’m still not as late as your checks!'”

You’d think the pressures of negotiating New York traffic, running from session to session, playing jungles one minute and album tracks the next, working out part of songs you have never heard before, hoping like hell that what you play is indeed what’s needed to be played, skipping lunch and sometimes supper, too, trying to make it back to Brooklyn in time to see the wife and kids before bedtime – you’d think that after nearly 20 years of all this, Allan Schwartzberg, one of New York’s elite session drummers, would be tired of the heavy grind.

“I love it,” the admitted workaholic and perfectionist laughs. “I really do. I love being busy. I love making music and good money. I like it best when I’m so busy that I don’t even have time to think.”

Allan Schwartzberg is busy. There’s no denying that, especially not today. It starts the night before, like it always does. He checks in with Registry: three messages, three sessions. He checks his calendar. A couple of weeks ago he penciled in a live date with Maureen McGovern at the Twenty Twenty Club. Tomorrow his day will be consumed with work. That makes Allan Schwartzberg smile.

That night Schwartzberg calls me and says, “Come into the city tomorrow. It’s a good day. You’ll get a good idea of what I’m about and what this business is about. Meet me at 10:00 at Hip Pockets Studio on West 20th Street.”

The next day I arrive on time. Allan is already behind his drumset. He’s working on a fill to add to the Budweiser beer jingle he and the other musicians hired for the session will be cutting in a few minutes. They’ll have but an hour to learn it, perfect it, and record it.

The producer calls the session to order. He announces some last-second changes. Then Schwartzberg and the rest of the musicians run through the jingle, which will be sung in Spanish by Jose Feliciano later on and used to sell beer south of the border.

The producer calls the session to order. He announces some last-second changes. Then Schwartzberg and the rest of the musicians run through the jingle, which will be sung in Spanish by Jose Feliciano later on and used to sell beer south of the border.

“Again,” says the producer. “Let’s change the intro. Two beats of C, then another beat, and we’re off.” The session players do it again. The producer confers with the engineer in the control room. In the studio, the guitarists chat and Schwartzberg stretches.

The producer is back. “One more,” he says. In all, there are close to 20 attempts to make the jingle right. But by the end of the hour the producer has something he can take back to Budweiser and feel good about.

While the other musicians pack up, Allan comes over to me and introduces himself. “Funny, you don’t look Italian,” he says. “Come on, we’ve got to go. We can talk in the car on the way to my next session. It’s in 30 minutes, and I’ve got to drop off two friends.”

RS: You’re a very successful New York session drummer. You’ve been doing this sort of thing for a long time. Others like yourself have come and gone. What’s your secret? How do you stay in demand?

AS: It mostly has to do with talent and knowing how to get along with the right kinds of people. There are a bunch of musicians that are in the bull’s eye. The difference between us could boil down to who brings the best work attitude to the session – who does this producer want to spend some hours with.

RS: You’re in the bull’s eye, no?

AS: Yeah, you could say that. It’s been that way for quite some time.

RS: And how, exactly, did you get there? Can you be specific?

AS: I have a reputation for caring about my performance and what my playing sounds like. I never walk into a session without that attitude. It’s my ego problem that’s working to the producer’s advantage. Everyone gains by it. The drums are an unbelievably important instrument. It’s the motor that runs the beautiful car. If I’m happy with my drum performance, then the people who hired me and believe in my abilities are going to be happy. What makes me happy is a great performance. It doesn’t have to be a showy type of performance. Also, I don’t care who comes up with what I play. The music is what’s important, and in the end I’ll get credit for it anyway.

RS: Let’s go back a bit in time. How did you get into session work in the first place?

AS: For a long time I was a jazz player. I used to be the house drummer at a place in New York called the Half Note. I played with guys like Jim Hall, Ron Carter, Zoot Sims. I also went on the road for a little bit with Stan Getz. I wasn’t really having fun, though. I definitely wasn’t making any money. My bar bills were much more than I was getting paid. This was 18 years ago. I used to eat, sleep, and live jazz. All I wanted to be was a drummer who played like a combination of Elvin Jones and Tony Williams.

RS: You and lot of other drummers.

AS: That’s definitely true. But see, I realized I wasn’t happy, and neither were most of the other jazzers then. So I left it. At the time, jazz was going through a severe depression. No one was listening to that music in, say, 1969 and 1970. It was terrible. I had to survive somehow. And I wanted above all to keep playing the drums.

AS: That’s definitely true. But see, I realized I wasn’t happy, and neither were most of the other jazzers then. So I left it. At the time, jazz was going through a severe depression. No one was listening to that music in, say, 1969 and 1970. It was terrible. I had to survive somehow. And I wanted above all to keep playing the drums.

RS: Were you married at the time/

AS: Yeah, but it wasn’t to the right girl. It wasn’t the take, if you know what I mean. But I’ve since remarried. I’m very happily married now, with two beautiful, loud kids.

RS: Having a wife and not making any money must have been tough.

AS: It was. Plus, I just wasn’t having any fun playing jazz.

RS: So what happened? How did you change gears?

AS: I heard Roger Hawkins’ first backbeat on Aretha Franklin’s “Chain, Chain, Chain” record. Then I heard a James Brown record called “Got the Feeling.” You’ve got to understand that I never cared about any music but jazz back then. Growing up, I didn’t even listen to the Beatles because their time was all over the place. But when I heard Aretha and James Brown, well, their music just went up my spine. What they sang was as cookin’ as anything I had ever heard. I discovered other acts, like the Meters. So, basically, I came into contemporary music through R&B. It was more of a logical channel for me than to pursue rock ‘n roll, because R&B is more closely associated with jazz.

RS: Was this a gradual or an abrupt transition?

AS: It was gradual. It really didn’t happen overnight. But I knew things were coming along when I played on some of James Brown’s records, and he liked me a lot. It was a great accomplishment for me to have The King of Soul think that this Bar Mitzvah boy had some, too.

RS: Did you also start to discover rock ‘n roll at this time?

AS: Yeah. I started hearing and loving the Beatles the way other people were. I listened to a lot of other things, too, like Little Feat, Led Zep, and Hendrix.

RS: What about recording and making records back then? What was your approach?

AS: First of all, there was a lot more of it then – single artists without bands, and lead singers wanting to stretch out without their regular guys. I felt at home in the studio. I loved the control. All jazz records back then were one take. Three hours in the studio, and you had yourself an album. I never got into that concept of recording. I like the idea of being able to perfect what you play. I think my approach has always been the same: trying to find the perfect beat for a particular piece of music. It’s like making records the way composers write songs.

RS: How did you work your way into steady session work?

AS: It was just like today, you have to know the right people and they have to love you. You either have to have an uncle who owns a recording studio and who can introduce you to all those people you need to know, or you have to be an amazing player who can cover all kinds of music so well that producers are practically forced to hire you. Those were the only two ways to break into the studio back then, and it’s the same way now.

A bass player named Don Payne gave me a shot at doing jungles. The first one I ever did was for Kent cigarettes. I went into the studio and worked as hard as I could so that what I came up with sounded special. I tuned the drums before the session, which nobody was doing then. Studio guys had a tendency to get a bit jaded. They usually walked in and played the drums just the way they found them. In New York, every studio has its own set. But I didn’t like the way the drums sounded, so I tuned them. Everyone was pretty surprised by this. Then, I’d always ask for another take if I didn’t think the producer got my best performance. I’d always go into me control room and listen to the playback, which wasn’t common for musicians to do in those days. I really cared. Every little dinky demo I did, I cared about. It turned out to be to my benefit. Word got around. I was a new face, a new guy, and producers were looking for new faces. Producers are still always looking for new faces, which is a bitch. That’s why I always feel the pressure of staying one step ahead of everyone in the business.

RS: You seem to thrive on pressure.

AS: Yeah, but I’m not so sure it’s healthy. I mean, I did 30 sessions in a week on a number of occasions during the late ’70s and early ’80s. Talk about pressure – I feel okay now, but I’m not sure I want to see the X-rays.

RS: How did you come up with a steady stream of good ideas and quality performances with that kind of workload?

AS: There were some tough spots. There are some people who still don’t like me because of the way I was in those days. I got involved with drugs, and I did a lot of drinking. I was always on the edge. But I had to deal with the pressure somehow. Fortunately, I learned before it was too late that those substances turn you into an aggressive asshole with too many suggestions.

RS: So you’ve given up drugs and alcohol?

AS: With the exception of an occasional beer, yes. I stay away from both booze and drugs. They could have and would have destroyed my career like they destroyed the careers of so many other studio musicians. I used to call what I took “Einstein”; now I call it “losing powder.” I didn’t want to lose, so I just stopped using drugs cold. I haven’t touched the stuff since. And I won’t, because I’m really frightened of losing what it took me so long to get.

RS: What about the business end of being a session musician? Is it as lucrative as many musicians say it is?

AS: It’s not as lucrative as it used to be, because there’s not the volume there used to be. But there are a bunch of us who are still cranking out a nice living. I’m not sure it compares to what, say, the drummer in Bon Jovi’s band is making, especially if he has a piece of the band and a good accountant. The money to be made in the studio scene is like it was in the late ’70s and early ’80s is not telling you the truth. It’s the technology that’s cutting into things, and it’s the quality of drumming that you hear from young drummers these days. I used to make a lot of money drumming for self-contained bands like Alice Cooper and Kiss when it came time for them to make a record.

AS: It’s not as lucrative as it used to be, because there’s not the volume there used to be. But there are a bunch of us who are still cranking out a nice living. I’m not sure it compares to what, say, the drummer in Bon Jovi’s band is making, especially if he has a piece of the band and a good accountant. The money to be made in the studio scene is like it was in the late ’70s and early ’80s is not telling you the truth. It’s the technology that’s cutting into things, and it’s the quality of drumming that you hear from young drummers these days. I used to make a lot of money drumming for self-contained bands like Alice Cooper and Kiss when it came time for them to make a record.

RS: You haven’t just done studio work. I know you’ve toured with some name artists in the past.

AS: I went on the road with Peter Gabriel, Mountain, B.J. Thomas, Pat Travers, and a few others.

RS: Is there a reason why you haven’t done more touring?

AS: I never thought I’d enjoy playing the same songs every night. But lately I’ve been itching to go on the road. Every so often it’s a refreshing experience. At one time I even thought I might want to join a full-time working band. I seriously thought about joining Journey a couple of years ago. This is a funny story. The band flew me out to California to audition. I was flattered that they did that. Later, I found out there were 50 drummers auditioning before me as well as after me. Anyway, I practiced for about a week before the audition. I learned all Journey’s songs. At the audition I played as hard as I could for the first tune. I’m a big believer in first impressions. Well, the band liked what they heard. A couple of guys said, “Hey, that was pretty good. Let’s do it again.” I said, “Wait,” huffing and puffing. “Whoa, let’s just take a minute.” You could see my heart pounding through my shirt. Well, that was it for me. They didn’t want me to die right there at the audition.

After that, I knew I was crazy to think I could play 38 songs a night with a band like Journey. Session work is the right kind of work for me. I belong in the recording studio. When I get behind a good set of drums, and I look around at all of the great musicians I’m playing with, I feel comfortable, satisfied, and at home.

It is 11:45 A.M., and we are in the midtown Manhattan office building where Crushing Enterprises is located. Allan is here to do some drum programming and overdubbing for a Pillsbury project.

After a few hellos, Schwartzberg is handed the music for the jingle. He steps into one of the recording cubicles, which seems to have been a broom closet before the office space on the floor was made into a maze of tiny recording rooms, complete with the latest recording equipment.

Schwartzberg sits down with his Linn 9000. It’s a tight fit. He remarks that such facilities are the wave of the recording future. “You don’t need to go into a traditional studio anymore to cut a jingle,” he says. “What I have to do for the next hour or so can be done in this little bit of a room. The accent is on cost efficiency.”

Schwartzberg works through the music. It’s not the most challenging work; in fact, Schwartzberg fights off boredom as he adds electronic drums to what is a pretty catchy melody.

RS: You’re not the world’s biggest fan of drum machines, are you?

AS: Yes and no. The electronics thing that’s been occurring in music was difficult for me to accept at first. It’s only been in the past four years that I really got into modern drum technology. I love the sonics of the electronic drum technology, and certain things are almost impossible to play any other way, but there are uncomfortable areas for me.

RS: Why is that?

AS: Because there are hidden factors. Things go wrong, and I don’t know why. That really bothers me. When I use a drum machine, I’m speaking through an instrument that’s cold and sometimes insensitive. It’s not a direct means of musical communication as far as I’m concerned. I do feel I can program anything that I can play, yet there are things that make me uneasy. Take, for instance, this piece that I’m working on. Something could happen three quarters of the way through the session. The Linn could go down. It could simply crash. Then I’d have to start all over again. It’s nerve-racking more than anything else, I guess. That’s especially true when I’m dealing with the 9000. It’s the best-feeling drum machine on the market, but it can give you a heart condition.

RS: Did you get into drum programming out of necessity?

AS: Yes. A good friend of mine, Steve Shaeffer, who does the first-call film work in California, just about threatened my life it I didn’t learn how to program. He said to me, “Allan, you’re not going to make a living if you don’t. You’re going to be an old guy like those die-hard beboppers.” He saw the handwriting on the wall. He was definitely right. Not only do people really want you to use a drum machine in the studio, but having a machine like the Linn and knowing how to program is a definite indication of whether or not you’re really “here” in the present. If you’re not dealing with electronics, you’re not happening in the session world. A session player like me has to keep up with technology. It’s that simple.

RS: What kinds of electronic equipment do you find yourself using most in the studio?

AS: I use the Linn 9000, Octapads, and tons of samples that I’ve made and traded with Sammy Merindino, who is, without a doubt, the absolute champ at this stuff. My equipment is the kind that I can break down, pack up, put under my arm, and take to the studio. Any other equipment I’ll get from the studio itself. Most of the studios I work at have great outboard equipment and great engineers. Why not take advantage of that? I set up Yamaha MIDI pads for the toms and mount Octapads on the hi-hat stand to play live percussion and sound effects, like cymbal swells, backward sounds, etc.

RS: What are your feelings about he relationship between percussion and drums?

AS: Percussion is great fun to play. It’s the icing on the cake, or it can be the whole feel itself. Percussion and drums together make the rhythmic fabric. Try to imagine the Miami Sound Machine without percussion.

The late Jimmy Maelen was the best there ever was at doing that stuff. He had an overview that very few possess, and he could find slots in the music that you didn’t know were there. We worked together almost every day. Playing with live percussion is such a treat for a drummer, especially with someone like Maelen. Ask Andy Newmark about that. Jimmy was a rock. He was my dearest friend.

RS: Is there a difference in the level of satisfaction you experience when you complete a drum programming session as opposed to a session where you used acoustic drums?

AS: Oh, yeah. When I finish programming a drum part, it’s like a wet dream. I did everything in the dream that I would do when I’m awake, but I didn’t really DO anything. It’s an artificial sense of satisfaction. That’s a weird analogy, but it’s true.

RS: These days a lot of keyboard players are getting involved in drum programming. How do you feel about that intrusion into a drummer’s territory?

AS: It’s scary to hear some of the drum parts that non-drummers are coming up with today. Most of them suck and have a stupid, robotic feel. I asked Steve Shaeffer what he says when he hears a great drum program by a keyboard player. You know what he told me? “Don’t say anything. Don’t tell him it’s good. Let’s try to keep keyboard players at the keyboards.”

While the rest of the staff at Crushing sits down to a lunch of friend chicken and rice made by the resident cook, Schwartzberg and the producer of the jingle go over programming details. Schwartzberg has time for a couple of bites of an apple and a swig of beer, but no lunch.

Next up is overdubbing. To watch Allan work is to witness an exercise in concentration. He immerses himself in the music and doesn’t come up for air. He checks and rechecks his work, and he continuously tries to improve upon it until he’s exhausted every possible idea in his head. For someone who says he’s not completely comfortable with electronics, Schwartzberg is indeed in command of the instrument. It’s no wonder nearly a third of the studio work he does involves his drum machine.

RS: How and why did you become a drummer?

AS: This is strange, but honest, it’s absolutely true. I’ve told this story before. I don’t know how many people believe it, though. There was a magical moment in my life when I was about eight years old. I was on my way to school one day when I heard a Gene Krupa record. Somebody was playing it in an apartment, and the music was escaping through an open window. It was incredible. I froze in my tracks. I mean, it was like a mystical experience of something. I went into a trance. It was as if somebody reached into my body and turned on a switch. When I went home later that day, I immediately began banging on the table and the side of the washing machine. You have to understand that there are no musicians in my family. Everyone is either a doctor or a lawyer or a jeweler. But I pleaded with my parents to buy me a set of drums, which, fortunately for me, they did.

RS: You don’t get to hear stories about musicians who experienced such single, profound awakenings as you did, at least not that often.

AS: It was really crazy. I mean, who knows where this fascination with drums came from? I never even heard anyone play drums before that day. I’ll never forget it as long a s I live. The only other mystical experience I’ve ever had was when I made eye contact with my wife, Susan, for the first time.

RS: Did your parents support you in your early musical endeavors?

AS: They bought me a set of drums. But, generally, they tried to discourage me from pursuing music as a career. They knew the music business was a shaky business. They wanted me to become a doctor or a lawyer.

RS: But you persisted and stuck with the drums.

AS: That’s right. I was very much into sports as a kid. But when I discovered the drums, I gave up sports. I just gave them up. One day I was playing baseball, I was standing there in e outfield, and I suddenly said, “Screw this!” Something clicked in my brain that forced me to walk off the field in the middle of the game. That was it. I went home to practice the drums. I practiced eight hours a day. I’d go into a trance while I was practicing. I’d memorize Max Roach solos and just imitate drummers.

RS: Your musical focus was primarily jazz?

AS: I didn’t notice any other music.

RS: But, growing up in the ’50s, weren’t you affected by Elvis Presley and the birth of rock ‘n roll?

AS: No. Ironically, I love that stuff now, but at the time, I didn’t notice a thing. When I got past the Gene Krupa fascination, I turned my attention to black jazz drummers. I loved Philly Joe Jones and Pete LaRoca and Max Roach. I bought everything that Elvin Jones ever played on. I loved Tony Williams’ drum style. I still do. Later on, I worked across the street from where Elvin Jones was playing, and I got to know him. Philly Joe Jones, though, was so great, I couldn’t even begin to emulate his style of playing. Elvin Jones seemed easier for me to imitate.

RS: Do you remember your first set of drums?

AS: Oh, yeah. It was a Gretsch set. I’ve been so lucky. As a kid I lived in an apartment house with neighbors on all sides. I used to practice all day, and the neighbors didn’t mind. I lucked out · or maybe they moved out.

RS: Did you take drum lessons when you were a kid?

AS: I studied drums with a guy named Sammy Ulana, who became an inspiration of sorts to me. He embarrassed me into practicing. He made me feel bad if I didn’t practice. He was the only real drum teacher I had. He taught me how to read. I learned everything else from records. So, in a way, Tony Williams, Elvin, and Philly Joe were my teachers. Later on, Keltner and Roger Hawkins were teachers. I can say the same thing about Bernard Purdie, who I thought was absolutely great. Purdie has got to be given credit for inventing the “groove.” Nobody grooves as hard as he does. He’s the missing link between rock ‘n roll, rhythm & blues, and jazz. Everyone has stolen from him in one capacity or another.

Schwartzberg completes the overdubs, packs up his Linn, and is on the move again. Next up: session number three – a simple overdub jingle session. Then there’s number four. Schwartzberg says he’s looking forward to this one, since he’ll be cutting gone or two rhythm tracks for an upcoming Linda Ronstadt album. We get into the car and again confront midtown traffic. Our destination is Automated Studios on 43rd and Broadway.

On the way, Schwartzberg talks about the session he just completed. “It’s a funny thing,” he says. “I’ve been doing this session thing for a long time. But every time I record, there’s a slight fear that’s left inside me. It comes from, I don’t know, maybe an uncertainty about my performance. Something inside me always asks, “Was that the best you could play?”

We inch our way to the studio. Rush hour has begun. We make it to Automated with minutes to spare. Guitarist John Tropea, a close friend of Schwartzberg, greets us. He tells us there will be a bit of a delay. Allan doesn’t complain. He’ll get paid for a few minutes of relaxation. It’s the first bit of leisure he’s experienced all day.

RS: What’s the difference, if any, between the New York session scene and the one in L.A.?

AS: Sometimes I think the L.A. scene is the opposite of what we have here in New York. Out in L.A., things seem so amazingly elegant, compared to New York, which one might consider the slums. At L.A. studios there are parking spaces for the musicians. What a luxury. The equipment scene is completely different. Everybody in L.A owns tons of stuff, and it’s all carted to every session where it’s played in huge rooms. Here we have mostly little rooms and people jumping in and out of cabs. In New York we take back-to-back sessions. Out in L.A., a session player might take a session from 10:00 to 1:00 and maybe another one from 2:00 to 5:00. They have to have space between sessions. Here in New York I can take a session from 10:00 to 11:00, from 11:30 to 12:30, from 1:00 to 2:00, an so on. Musicians do a lot of film work in L.A. In New York we do a lot of jingles. The film work pays a lot, I might add, which is good for those guys. They get a Motion Picture Fund check at the end of the year. New York session musicians get residuals from the jingles they play on. Most of the jingles in the U.S. are done here in New York. I think there are more record dates going on in L.A., though.

RS: Which scene do you think is more competitive?

AS: Somebody in the business once said you can see the knife coming in New York, but in L.A. you don’t. I’ve always enjoyed working in L.A., and I’ve been doing some writing for a show out there. I’ve written some things with John [Tropea]. We wrote the whole music package for a TV show called Hour Magazine. We’re going to try to do some more of that.

But, to answer your question, I used to feel this competition thing you’re referring to. I must admit that I always felt like a kid from a poor neighborhood whenever I went out to work in L.A. There is less of a pressure factor out there. If you’re out of work in New York, you’re a goner. If you’re starving in L.A., you can always pick an avocado off a tree and whip up some guacamole.

RS: Is there such a thing as a “New York” feel when one talks about New York session drummers?

AS: I think there is. It’s the type of thing that has to do with intensity. The old saying is that New York drummers play on top of the click, while L.A. drummers play behind it. I’m not sure that’s true, but it might be. We’re on top of the click because there’s millions of people jammed into one town, talented, competitive, nervous, and freezing their asses off in the winter. We’re a product of our environment.”

RS: You seem to read music rather well. Is that a basic requirement for session players?

AS: For me it is. Reading music is easy – same as a newspaper. There is really no reason why a session player can’t read. But there are some musicians who can’t read and still manage. The bottom line is that most session musicians read.

RS: What happens to a session drummer who can’t read when a producer hands out sheet music and says, “Play this”?

AS: Well, that musician better have great ears. Sometimes a producer will say, “Okay guys, get out your pencils and change the piece so that when we go back to the top we cut out the last three bars and make the fourth bar 3/4,” or something to that effect. Now, for someone who’s just learned the music and who can’t read, well, he has to relearn the piece. It’s going to take him at least two to three attempts to get it right. The other guys around him will play the piece in its revised form and probably won’t make any mistakes. Often, they’ll get annoyed at the drummer who can’t read. You can’t really blame them.

It’s a funny thing about playing drums. When something is not feeling good tat a session or in a band, all sights – as in gun sights – are on the drummer. You’re the engine of the band. A drummer can’t afford a bad day. A session drummer isn’t in a band. But – and this is important – he’s supposed to sound like he’s in a band, and he’s supposed to make everyone else in the studio sound like they’re in a band, too.

A producer hires me knowing that I’m going to take this music he’s just handed me, and I’m going to interpret it and produce on my instrument. That’s what I really am – a drum producer. I produce drum parts. You can’t play what’s written in the music. Very few people know how to write for drums. Van McCoy was one of the exceptions. John Tropea is an exception.

Speaking of Tropea, he enters the room Allan and I have been talking in and calls Allan back into the studio. The equipment is finally set up, and he overdubs three drum fills in a Pizza Hut commercial. Then we’re out of there and on our way to the last session at Sunset Sound. Schwartzberg and the others will work on one Ronstadt rhythm track. Despite three previous sessions, no lunch or supper, a number of mini-interviews conducted by yours truly, and the frustration that goes with working in Manhattan (traffic, parking, etc.), Allan is as sharp as a tack for this session. What he plays seems perfectly tailored for the song he and the other musicians work on that night.

I begin to think that Schwartzberg’s true talent – and that of any successful studio drummer – is his staying power. Allan rarely loses his edge. He seems to be able to call up an energy reserve and a heightened set of concentration skills when an ordinary drummer would be ready to pack it in for the day. The result is that the last session of the day for Schwartzberg often sounds as fresh and rewarding as the first.

Schwartzberg is at Sunset Studios until 8:30 P.M. He leaves his drums at the studio and races down to the Twenty Twenty Club where Maureen McGovern is nervously waiting for him. In minutes he’s on stage with her and her band. After the set, which is about an hour long, I get to speak with Schwartzberg one more time.

RS: It’s been a long day.

AS: Yeah, but the pace and the workload are things you get used to. I’m probably not as tired as you are.

RS: You’re probably right. You’ve played a number of roles today. You cut three jungles, did an album track, and played a live date. Does it ever get a bit overwhelming?

AS: I feel like I’m a character actor. Years ago, before Robert Duvall became famous as an actor, I often identified with him. Duvall used to be a guy whose face you knew, but you didn’t know his name, even if he was so believable in so many roles. That’s the way I see myself. I’m not a star like Steve or Dave (laughs). I just blew it. I was hoping that this would be the first drum interview that didn’t mention Gadd and Weckl.

As for my drumming, I have certain identifiable things – emotional tom-tom fills, nice colors in sensitive parts, things like that. I try to take a drum part as far as I can without the drums sticking out or showing off. I say to myself, “What’s the most I can do with this piece of music?” I’ll do some inventive things when I can. Once I put a beer bottle on top of the hi-hat stand, I played the hi-hat and the bottle and got this high-pitched glass sound just before the backbeat. I don’t ever see myself playing in a boring fashion. I always try to play with some wit. I consider Keltner, Richie Hayward, B.J. Wilson, and old timer Sol Gubin to be really witty drummers.

RS: It seems like you always try to use Yamaha drums.

AS: I endorse Yamaha drums. I only went after a drum endorsement once, and that’s when I discovered Yamaha drums. I was knocked out by their drums. I even got most of the studios in town to buy Yamaha equipment. Almost every studio of note in Manhattan now has a Yamaha drumset on the premises.

RS: What’s the ideal setup for you?

AS: I like to play the Recording series. That’s the set I own. I have a 20″ bass drum, and 10″, 13″ and 16″ toms, plus the Yamaha electronic pads. I only use Vic Firth sticks, and only Zildjian cymbals. My hi-hats are 14″ Zildjians. One of my favorite pieces equipment, which isn’t a Yamaha, happens to be a Roland mount that fits anything that’s cylindrical. What this means to me is that I can mount my Octapads on anything that has a pole.

RS: Do you still practice?

AS: When I do things at sessions or live dates that I’m not happy with, or when I know I could have played better, I go home and practice. It could be something really basic, like straight 8th-note bass drum pattern. But if I don’t do it just right – like I might have a little “skipping” feeling, a slight dotted-out feel, in the playback – I’ll go home and practice that.

RS: How many other session drummers react the same way to a less than perfect session as you do?

AS: I don’t know. Probably not too many.

RS: How many session drummers are there in the business who are making a good living and are working regularly?

AS: I’d say there are about eight of us. I’m not including great players like Steve Gadd or Dave Weckl; they’re on the road a lot. So the top six or so drummers are working five days a week. Drummers seven and eight are probably working four days a week.

RS: You obviously work five days a week.

AS: Most of the time.

RS: Could you, if you wanted to, work more?

AS: No, I don’t think so. It’s pretty much a five-day-a-week situation. I would work seven if the music was worthwhile and the money was good, though. I recently did a great album project with Elliot Randall, Elliot Easton, and Will Lee that stretched into the weekend, but it was worth it because the music was so good.

RS: What are the down sides of being a session drummer in New York?

AS: You could, one day, find yourself staring at the telephone. Remember, people have to ask you to show up at a session.

RS: Did you ever find yourself staring at the phone?

AS: No, it hasn’t happened to me, thank God. I’m waiting for it to happen, though. I’m always thinking that it’s going to happen today or tomorrow or the next day. I live in fear of the phone not ringing. I might get a call for only one session today and maybe nothing for the rest of the week. Then I start thinking, “Maybe this is the week that it all ends.” A guitar player I know recently told me that he hasn’t worked in three weeks. He said the calls just stopped coming.

RS: If the studio work did, in fact, dry up for you, would you stay in music? Or would you do something else with your life?

AS: Oh, I’d stay in music. Actually, I’m very prepared for the day when I don’t have to play drums. I love producing records. I have a jingle company called Picture Music. I’ve written, co-written, and arranged jingles. I’m ready.

RS: The classic gripe against a session player is this: He’s a hired gun. He has no real emotional connection to the music. To him the song is just another song and the session just another session. How do you respond to that?

AS: It’s a stigma that some of us are trying to live down. Let’s fact it, there are some session players out there who sound like machines. I think some studio musicians would be the first ones to admit that n certain kick-ass rock passages, it doesn’t quite sound like they’re playing standing up. You have to play believably. You strive to sound believable all the time. You know what I’m most proud of?

RS: What’s that?

AS: That I was able to play live gigs with Stan Getz, Mountain, and Peter Gabriel in one career.

RS: You even got to put your drum mark on some of Jimi Hendrix’s music too, right?

AS: That’s right. I met Hendrix once. I was playing with Mose Allison at the time. I thought Hendrix was kind of a noisy player. He and his band were playing opposite us. He was a loud and lunatic kind of player. Later on I did a thing at Media Sound here in New York where I overdubbed the drum parts on some Hendrix tracks that were released after he had died. We could all swear that the session was spooked. Bars didn’t count out right and other weird things occurred. That was a tough job for me because those guys [Hendrix and his band] were wrecked when they played. I had to trace the tempo – or should I say tempos. I remember Hendrix counting off once. It went something like this: “One, two,” and then in another tempo, “one· two·, three·.” The records were Crash Landing and Midnight Landing.

RS: Have you done a lot of this sort of work in the past?

AS: I’d say so. I also overdubbed a lot of Sly Stone stuff. I was amazed at how uneven the time was on Sly’s material. They didn’t use a click track back then. Fortunately, everyone was uneven together. Like the Beatles.

RS: What are some of the other albums you played on at you’re especially proud of?

AS: Roxy Music’s Flesh And Blood. I played on Peter Gabriel’s first solo album, which is a great one. I also played on Alice Cooper and Kiss records. I did a lot of the disco records in the mid-’70s. In fact, I have the dubious distinction of being credited with creating the disco beat on Gloria Gaynor’s “Never Can Say Goodbye.”

AS: Roxy Music’s Flesh And Blood. I played on Peter Gabriel’s first solo album, which is a great one. I also played on Alice Cooper and Kiss records. I did a lot of the disco records in the mid-’70s. In fact, I have the dubious distinction of being credited with creating the disco beat on Gloria Gaynor’s “Never Can Say Goodbye.”

RS: One thing you’ve done a few times over the past few years is sub on the Letterman show. What’s that like?

AS: Best job of all time. It’s 4:00 to 6:30 in the afternoon, when nothing else is going on around town. [laughs] You play with a hot band with hot music guests, your mother sees you on TV, and you make a nice taste. Paul Shaffer is the greatest – ten times funnier off camera.

RS: What contemporary drummers do you especially admire?

AS: I enjoy Jim Keltner, B.J. Wilson, Richie Hayward, and Sol Gubin. I love Mickey Curry because he plays the way I like to play. Steve Shaeffer is a great drummer. He has absolutely perfect time. Dave Weckl is a fantastic player. I also admire Jeff Porcaro.

RS: When you go home after a long day like this one, what do you do? Do you plop into a chair and relax?

AS: I go home at night and think about what I could have played on a session but didn’t. I’ll tap my fingers on the table as I’m waiting for dinner. I can’t shake the drums. I’m always worried about losing my edge. It’s a bitch. If I go into a slump, I’ll wonder if I’ll ever get out of it. I have moments where I’m really creative, but then every once in a while I’ll have to look at all the records on the wall. I’ll say to myself, “Wait a minute, you’ve accomplished all this. Calm down. Besides, you’re booked tomorrow. Be cool.” But maybe that’s one of the true secrets about making it as a session drummer. Maybe it’s one of the reasons why I’m still here, still making a good living. I never come up for air. I keep digging, I keep pushing. Maybe that’s the way to stay around in the business. Anybody can climb up the session ladder. The trick is to stay up at the top once you get there.

RS: Is there anything in particular that you want to accomplish before you give all this up?

AS: I’d love to reach out and get into that zone of playing where the hands play all by themselves. In that zone you become a mere spectator; you watch your hands to the playing. I’ve experienced that a couple of times in the past. I’d like to get to the point where I’m doing it and experiencing it more often – that magical state of mind and body. I guess I just want to play like this drummer I hear in my dreams.