Buy

Resources

Entertainment

Magazine

Community

In This Article

Category:

Car Culture

Leo Beebe at Le Mans in 1966. All photos courtesy of Ford Motorsport.

Editor’s note: This piece comes to us from Hemmings reader and contributor Frank Comstock, a friend of the late Leo Beebe.

"Coming together is a beginning. Keeping together is progress. Working together is success." Henry Ford

"Great leaders inspire a sense of mission. Good people with a proper sense of mission will find a way to get the job done." Leo Beebe

Fifty years have elapsed since Ford Motor Company’s overwhelming victory at Le Mans in 1966 and the controversy over who did win, or who should have won, the race. Ford and its Director of Special Vehicles, Leo Beebe, were both praised and vilified in the motor sports world and press at the time and, in some ways, nothing has changed. The Internet teems with comments about the way the race ended, while online and print publications have returned to the fray in recent years, undoubtedly looking forward to this 50th anniversary.

Beebe (third from left) and his staff in 1965.

To understand the Le Mans effort for Ford in the middle 1960s means one has to think in terms of a team with a mission. As the overall leader of the Ford team, Leo Beebe understood his mission perfectly - Ford would win at Le Mans. Leo wasn't told to have a particular driver or pair of drivers win. He was told in simple terms by his old friend Henry Ford II to put a Ford car in the winners' circle at Le Mans. He also had to do the same at Daytona and Indianapolis, but there is no doubt that Le Mans was the main attraction. Henry Ford wanted to beat Ferrari and Le Mans was the place to do just that.

As one of Ford’s most trusted trouble shooters, Leo was known as a man who could bring order out of chaos. He knew that with each new challenge, he needed to assemble a team of experts and guide them to success. He knew he had to give credit to the team when success was assured and he understood he needed to take responsibility when failure or controversy happened.

The start of the 1966 race.

In the final hours of the 1966 Le Mans race, with only three of Ford’s eight team cars (and none of the five independent Fords) left in the fray, the squad began talking about how the race should end. The Miles/Hulme car was leading as the hours wound down, with the McLaren/Amon car initially a lap back, although they made up that lap when the Miles/Hulme car took a late pit stop. The Bucknum/Hutcherson car was several laps back, running in third place. Ford officials had their eyes on a win for the team, not on a win for any particular pair of drivers. A win for Ford as a team was the primary mission.

Opinions went back and forth during team discussions, but the decision ultimately rested with the leader of the team and Leo understood it was his responsibility. In an unpublished interview with noted automotive historian and author Dr. David Lewis, Leo said,“Ken Miles, who later died, regrettably didn't win the race that year. I had some real difficulties over that. But, he was a daredevil and I pulled him in and literally engineered the end of that race—-one, two, three… I called Ken Miles in and held him back because I was afraid the drivers would knock one another off. All you need is one good accident and you lose all your investment.”

Ford GT40s finish first, second and third at Le Mans in 1966.

Leo Levine, in his classic Ford: The Dust and the Glory delves into the story in more detail but with much the same result, noting that Beebe did not want to take a chance on a multi-million dollar investment by allowing the top cars to race to the finish. Beebe had counseled Miles at Sebring and again during the Le Mans race for taking what he considered unnecessary chances, while Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon had consistently followed team orders. Levine quotes Beebe as saying “Anyone can question the judgement, but no one can say it was not a consciously arrived-at decision—and on grounds we considered valid and just.”

The final result has been discussed ad infinitum and will probably continue to be discussed for years. Ford wanted the three cars to come across together. Miles backed off as they approached the line and McLaren arrived at the line one or two car lengths before Miles. Had they arrived in tandem as the Ford team wanted, McLaren would probably still have been the winner because they were on the same lap and a seemingly arcane rule then used at Le Mans would have determined the finish. The McLaren car had started a couple of spots back on the starting grid, thus traveling slightly further in 24 hours. So, if they had come across neck and neck, McLaren still would have won.

At Le Mans in 1966. Clearly, the number 13 proved lucky for Beebe.

I knew Leo Beebe and worked with him on several projects years ago. He never wavered from the published reports on who was responsible for the controversial finish at Le Mans in 1966—it was his responsibility as team leader and he made the decision that he thought was right at the time.

Leo had thoroughly enjoyed his time with Ford Racing once he got past the initial shock of three driver deaths (Dave McDonald, Eddie Sachs and Edward Glenn "Fireball" Roberts) in the first weeks of his tenure in 1964 and he was pleased that years after the successes of his team someone was still interested. I pushed hard to see if Henry Ford II had influenced the race-ending decision, but Leo wouldn't answer that question. He just pulled out the note from HFII he still carried in his wallet. It was so simple: “You better win”.

Three years of intense work—teamwork—performed by specialists assembled for the express mission of having Ford vehicles win all the major races in the world ended with wins for Ford in 1966 at Daytona, Indianapolis, and Le Mans, as well as at many other tracks. Controversy over the end of Le Mans aside, Leo Beebe and his team did exactly what they were instructed to do. It was a team effort and a team result.

Recent

Muscle Cars

All Five Factory-Sold Red, White and Blue AMC Performance Cars, Collected Under One Roof

Photo: Jeff Koch

By the mid-’60s, the muscle car wars raged ever onward. Every year brought hotter powertrains, better traction, wilder style—all at a price that even the local grocery-store bag boy could afford. Winners and losers were determined between the lights. Everyone seemed to want to get in on the action.

Everyone, that is, except for poor AMC. Formed by merging Nash and Hudson in 1954, AMC was small and cautious, chasing reliability and economy over trends. But Detroit overwhelmed Rambler’s compact-car raison d’etre, and by 1966 sales were in freefall. Cautious old management was replaced by Roy Chapin, Jr., a CEO who sought to capitalize on America’s performance awakening; Chapin’s family founded Hudson Motors, whose Twin-H-Power Hornet dominated early NASCAR tracks. He understood that racing would attract a newer, younger clientele.

A variety of crucial pieces to the company’s high-performance puzzle were either on-line or coming soon. A new 290-cube V-8 engine launched mid-1966; a bored-and-stroked 315-horse, 390-cube version would arrive in ’68; the upcoming two-seat 1968 AMX and its Javelin pony car counterpart looked promising. Chapin’s team worked to put it all together, mix in a dose of American pride and wink-wink psychedelia, and mount a sales campaign designed to make AMC sexier. Red, white, and blue (RWB) became the company’s signature high-performance palette.

The push started early as Javelins signed up for the SCCA’s Trans-Am road racing series. A black-and-white February ’68 sales bulletin showed pictures of the RWB scheme on a Javelin, days before it debuted at Daytona, and provided Rinshed-Mason and Sherwin-Williams paint codes for dealers to paint their cars. “When you see the cars in person or see color pictures, we think you will agree that the color scheme really looks like a winner!” A string of second place finishes (at War Bonnet, Bridgehampton, Meadowdale, St. Jovite, Bryar Park, and Riverside) were seen as moral victories from a team that had a fraction of the budget that the competition played with. Also, Craig Breedlove’s record-setting RWB Javelins and AMXs helped reinforce the concept in November of ’68. These helped cement the tri-color scheme in car buyers’ minds as the year progressed.

The most outrageous of the factory-painted RWB models to break cover was the 1969 Super Stock AMX. As AMC sought to hype its new performance outlook, Hurst Performance Research’s George Hurst and Doc Watson sought to follow up on the group’s successful Hemi Mopar A-body project for ’68. Plans fell together quickly, and by February of ’69, AMC introduced its SS/AMX to the Southern California Dealers Association meeting at Riverside, where hot-shoe Shirley Shahan—newly signed to AMC—made some demo runs. (She would go on to set a new SS/D record in her AMX that year.) NHRA also mandated a minimum of 50 cars to be built; AMC ended up building 52. All were delivered to Hurst as Frost White 390/four-speed cars, with 4.44:1 gears. While rebuilding the AMXs for racing, including going into the engine, Hurst took care of the RWB paint if the ordering dealer so specified, for a $79 surcharge. The restored "American Dream", the last to be built, was a factory RWB SS/AMX; it was shipped to Anchorage, Alaska, and lived a surprising life - much of it shielded from the elements in a storage container. In its day, it ran consistent 10.50s in the cool Alaskan air.

The SS/AMX was designed to be a strip-only monster, but the 1969 SC/Rambler was arguably AMC’s most visible (and notorious) muscle car for the street. It was developed simultaneously with the SS/AMX. Keep in mind: the usual muscle car formula placed a full-size-car engine in a mid-sized body; AMC went a step further and put its biggest engine in its compact-car line. You could compare the compact Dodge Dart with either the 383 or the rare ’69-only 440 option, or maybe the big-block Chevy II Nova, but the Rambler was by far the most minimalist platform of the bunch. Built on the AMC Rambler Rogue hardtop, which was ending production to make way for the upcoming Hornet, the SC/Rambler was essentially a parts-bin special. AMC’s big 390-cube V-8 led the charge, with all cars receiving a Borg-Warner Super T-10 four-speed with Hurst shifter, 3.54 gears with Twin-Grip diff, an AMX-spec suspension package, heavy-duty cooling, a Sun tach strapped to the steering column, dual exhaust with glass-packs, charcoal interior with RWB headrests, blue painted styled steel wheels, Hurst badging, and more. The only option was a radio—but who could hear it over the glass-packs?

Photo: Jeff Koch

<p>SC/Ramblers were available in two different RWB color schemes: the "A" scheme (foreground) and the "B" scheme.</p>

Though Hurst gets credit for design and marketing, and received $200 per car for their efforts, SC/Ramblers were built on the Kenosha line. Most were white with red sides and a blue over-the-top stripe, with the scoop receiving bold “AIR” lettering and engine displacement callouts. AMC advertised a 14.3-second quarter-mile time—unheard-of in its day—although some press venues got their examples to go even quicker. All for $2,998 at your local AMC store.

Not all AMC dealers received a SC/Rambler; some suggested that if the graphics were toned down, they could probably sell one; at the same time, AMX production slowed to a point where an extra thousand 390s were lying around. Management solved this by extending SC/Rambler production. All of the mechanical bits remained, but the revised application of color included blue rockers, with the red side element reduced to a simple stripe. This became known as the “B-scheme,” with the red-side models retroactively dubbed “A-scheme” by enthusiasts. The B-scheme cars did without the hood/roof/trunk stripe. A total of 1,512 SC/Ramblers were built, with A-scheme examples produced 3:1 over the B-scheme.

With the Rogue making way for the Hornet in 1970, AMC once again turned to Hurst to develop a special model. Their answer: the 1970 Rebel “The Machine” (known also simply as the Rebel Machine), based on AMC’s mid-sized coupe. Beyond the RWB paint scheme, with blue rockers and hood/scoop plus a body-length red stripe, there was an RWB lower grille detail, functional hood scoop with integrated 8,000-rpm tach, and stamped-steel 15-inch Kelsey-Hayes wheels. A suite of engine improvements saw the power rating jump to 340 horses. All Machines featured bucket seats, a floor shifter, 3.54 gears, and dual exhaust that had proper mufflers.

But the Machine was also available with optional creature comforts: automatic transmission, A/C, power steering, and a vinyl top were on offer. Soon after production started, AMC allowed Machines to be painted other factory colors; doing so deleted the red and blue striping. It sounded like what the market wanted, but in a world of Hemi Mopars, Super Cobra Jet Torinos, and 450-horse LS6 Chevelles, the Machine was on its back foot from the start. Just 1,936 were made, roughly half in the signature RWB scheme seen here. Like the SC/Rambler before it, and the Hornet SC/360 (never available in RWB from the factory) after it, the Rebel Machine became a one-year-only proposition.

There was one other limited-run RWB AMC that Hurst had no hand in creating: the Trans-Am Javelin. While drag racing was a healthy part of AMC’s performance-car expansion into 1970, the road-racing crew at the SCCA were generating their own excitement. The Trans-Am series primarily starred American pony cars in the Over Two Liter class; with Mustangs, Cougars, Camaros, and more racing fender-to-fender, Trans-Am saw some of the most exciting racing of the era—and the Javelin would be in the thick of things from the get-go. AMC elected to build 100 RWB T/A Javelins to resemble the competition cars, and gave them the gumption to back up their brash looks: a ram-air-induction 390 fed by a scooped hood cribbed from the AMX, Hurst-shifted Borg-Warner T-10 four-speed, 3.91 gears with Twin-Grip, F70-14 tires on Magnum 500s, heavy-duty suspension and cooling, a 140-mph speedo, 8,000-rpm tach, high-level SST interior trim, plus custom-engineered front and rear spoilers.

Unlike Detroit’s hot small-block pony cars, the T/A Javelin wasn’t a homologation piece - just a low-production eyeball-grabber for select dealers. It was well-timed: though Ford dominated the season, AMC won three of the 11 Trans-Am events (at Bridgehampton, Road America, and Circuit Mont-Tremblant) with Mark Donohue piloting Roger Penske’s Javelin to the winner’s circle. The wheels seen here are Trans Am Race Engineering Superlites; while they’re not factory-correct, they are period-look reproductions of what the Trans-Am racers would have used.

Each of these five are powerful, limited-run muscle cars built by the lowest-production American manufacturer extant. Finding any one of them is difficult enough - production was low, the survival rate was lower, and not every model line was painted RWB exclusively. But all five? And ensuring that each was painted in AMC’s signature scheme by its builders? All, in one place, at one time? In one collection?

Photo: Jeff Koch

Dan Curtis, owner of the five RWB warriors pictured here, owns AZ AMC Restorations in Peoria, Arizona. The shop has been a full-time endeavor for about a dozen years, but Dan’s love for AMCs dates back to the ’68 390 four-speed AMX he street-raced in Massachusetts as far back as 1971. He confesses that he initially dismissed the whole RWB concept as “silly,” but has held on to an A-scheme SC/Rambler since the late ’90s. Dan claims he never sought the RWBs out, but rather accumulated them over time - almost accidentally. The B-scheme SC/Rambler was purchased from noted AMC authority Mark Fletcher, co-author of the Hurst Equipped book, where this example is also pictured. The seeds to obtain the SS/AMX were planted via a chance meeting in 2008, though the car wasn’t offered to Dan for another decade; its RWB status was incidental to it being the final SS/AMX built. Six months later, a friend offered Dan the T/A Javelin in a part-trade offer.

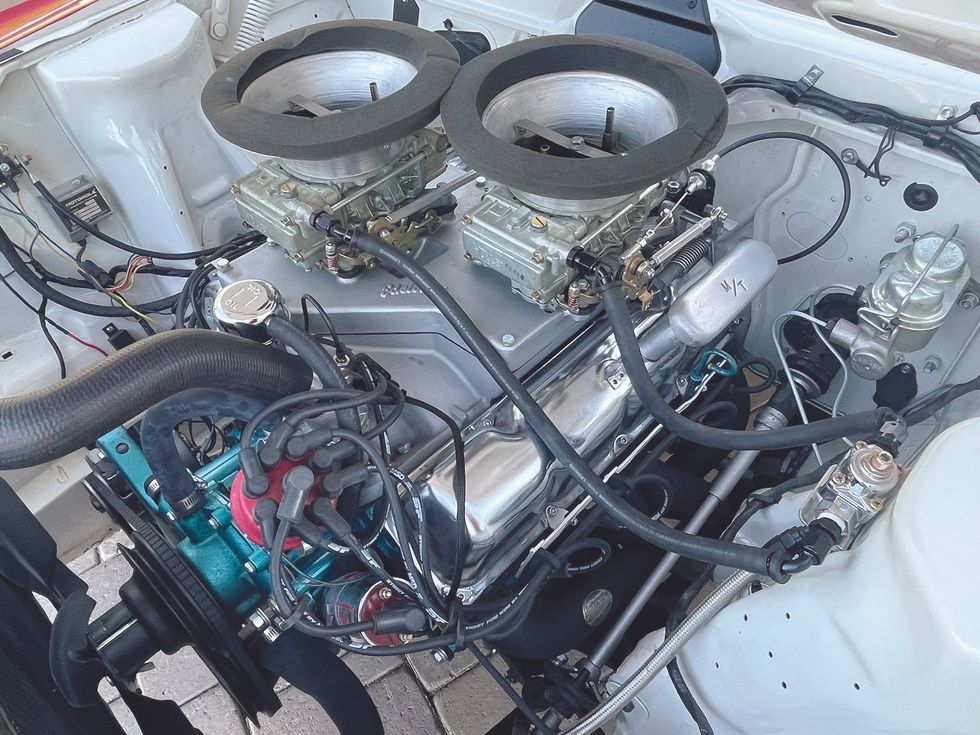

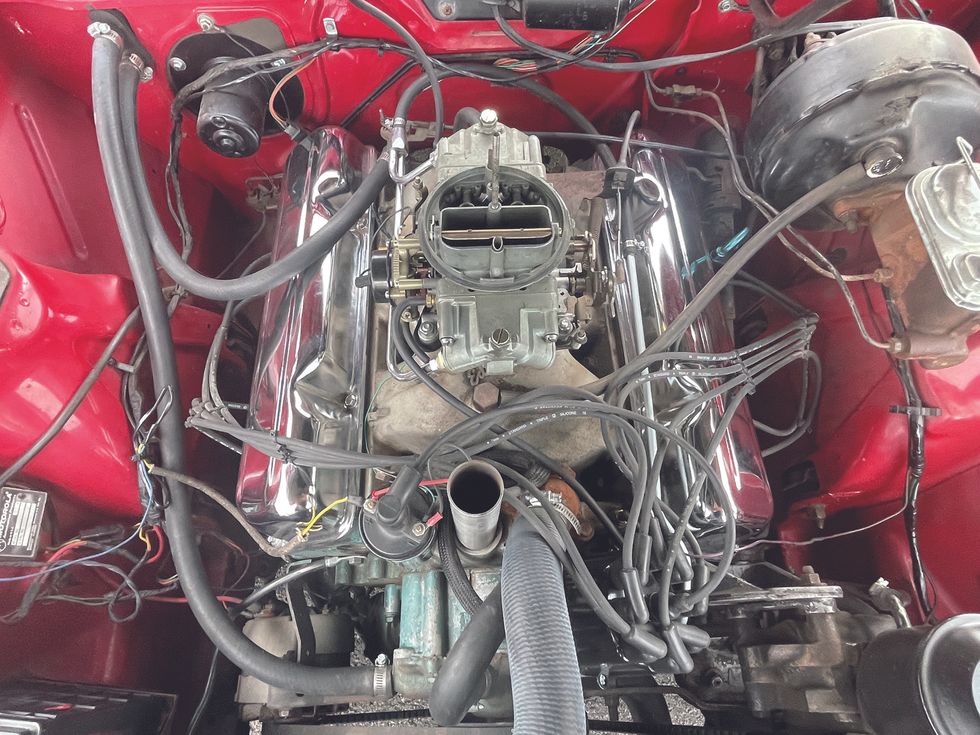

“This was late 2018 or early 2019,” Dan says. Soon, “I realized I had four out of the five - I only needed a Rebel Machine to complete the set. Then this Machine popped up in Las Vegas, and I thought, I can make this happen.” Dan points out that the only time you might see all five RWB cars together (other than on the pages of HMM, of course) would be at a national show - and that’s only if someone brought an SS/AMX. Other than his own, “I’ve never seen all five RWB cars together in a private collection.” All five of the cars seen here have been sorted out by his shop, including the installation of some genuine vintage over-the-counter AMC Group 19 parts under the hoods for a little extra kick. All of them are now ready to drive at a moment’s notice. They are shown regularly—whether singly or together—and Dan is happy to wave the flag for the forgotten and little-seen American muscle car contingency.

Keep reading...Show Less

Photo: Patrick Nichols

In 1967, to the relief of Ralph Nader, Don Yenko was moving away from building Corvair Stingers for SCCA homologation and started buying Camaros as the next product to be modified at the Yenko Sportscars facility in Canonsburg, Pennsylvania. Along with partner Dick Harrell, there were 60 Camaros built featuring the now-famous 427-swap into 350-powered, and later 396-powered Chevrolets that year. By 1969, Yenko also had a deal with Chevrolet to perform Yenko modifications on COPO 427 Chevelles and was looking at the Chevy II/Nova.

What Is A Yenko Nova?

Photo: Patrick Nichols

Chevrolet was supplying Yenko with factory 427-equipped Camaros and Chevelles via GM's Central Office Production Order (COPO) program to support Yenko's Super Car program. With Camaro and Chevelle production locked in, Yenko’s next plan was to add the Chevy II/Nova to the lineup. Since Chevrolet did not (some say would not) provide COPO 427-equipped Novas to the dealership, Yenko reverted to the original build plan used on the Camaros and Chevelles: they would order batches of cars from Chevrolet equipped with the L78 396-cu.in. engine and swap in one of two 427-cu.in. engines, depending on if the car had an automatic or four-speed transmission. There was a specific set of color codes for each batch, and each car was ordered with the Super Sport package to get the 396. Once the batches arrived, Yenko would add the rest. Depending on who you ask, there were between 37-40 Yenko Novas built in 1969. Today there are maybe 10 survivors.

Sold By Yenko And Hidden In A Garage

Photo: Patrick Nichols

In 2018, Chevelle authenticator Patrick Nichols received a tip from a stranger that there was an interesting Rallye Green 1969 Nova in White Oak, Pennsylvania, that had been parked in 1978. When Nichols called, the original owner, Dennis Michalo, was on the line with a story about a, L78-equipped Nova that he had purchased from Don Yenko in 1969. According to Michalo, he approached his local dealer in Duquesne, Pennsylvania looking for a base Nova equipped only with a “radio, Posi, and some other minor items.” More importantly, he was looking for an automatic. When he couldn’t find what he wanted, Michalo called Don Yenko in nearby Canonsburg who had a base model sitting on his lot. The Rallye Green 1969 Nova was basic. It had been ordered with the L78 SS396-engine, heavy duty suspension, rubber floor mats instead of carpet, no trim on the outside (except SS badges and hood), hubcaps on green rims, and an automatic transmission. Michalo bought it for $3,050 cash.

Because of the color (79/79 Rallye Green is one of four offered on 1969 Yenko Novas) the 731 black bench-seat interior, the L78 375hp 396 engine, and the date on which it was ordered, the prevailing theory is that this car was ordered by Don Yenko’s dealership in early 1969 as part of a batch of 20-22 cars to be converted to 427-powered Yenko S/C Novas, but was sold instead to Michalo before the job was done. There are other 396-powered Yenko /SC Novas that were sold through Yenko, but no record of any with an automatic. Is this to be considered an unconverted Yenko S/C Nova? Does it fit between the full 427 package of converted Yenco S/C Novas and the 396 four-speed Yenko Nova S/Cs that are out there? The debate is ongoing.

Where Is This Big-Block Nova Now?

Photo: Patrick Nichols

Nicols currently owns the Nova and has it stored in the “exact same condition” as it was found in 2018. Nichols says that he gathered all the parts in a bucket from Michalo’s garage and found the distributor and other parts in the trunk and trailered it to a storage facility located somewhere in Tennessee. Occasionally, he brings it out on a trailer for a cruise or car show, but mostly Nichols is hanging on to its originality.

Photo: Patrick Nichols

If anyone has any information or strong opinions about this automatic Nova sold by Don Yenko, its originals or authenticity, drop a comment below.

Photo: Patrick Nichols

Decoding the Nova's trim tag reveals:

- 02 D is fourth week of Feb 1969

- WRN is the Willow Run, Michigan, plant

- 731 is the base, bench seat, black interior

- 79/79 Rallye Green paint

Keep reading...Show Less

Interested in a new or late model used car?