Against Nature (Part I): The Art of À Rebours

Truth and fiction meet when a collection of real art pieces is carefully selected for the eccentric protagonist of a 19th-century novel

Benjamin Blake Evemy / MutualArt

Apr 23, 2024

In 1884, French author and art critic Joris-Karl Huysmans published the novel À rebours (in English: Against Nature), a tale concerning a character named Jean des Esseintes, a young aristocratic aesthete who decides to turn his back on the then-modern world and all of its banalities, and surround himself with only what truly and deeply appeals to the delight of his senses. Alongside meticulously chosen color schemes and furnishings, he also discerningly selects specific works of art from certain artists of which to hang inside his not-quite-sprawling sanctuary. Being no stranger to the art world, Huysmans included actual pieces in the work of fiction. Fantastical and unsettling, visceral and violent, eldritch and voluptuous, Des Esseintes’ carefully-curated collection serves a dual purpose beyond merely appeasing the ocular senses, and however disparate the pieces that comprise it may seem, there does exist a commonality that ties them together.

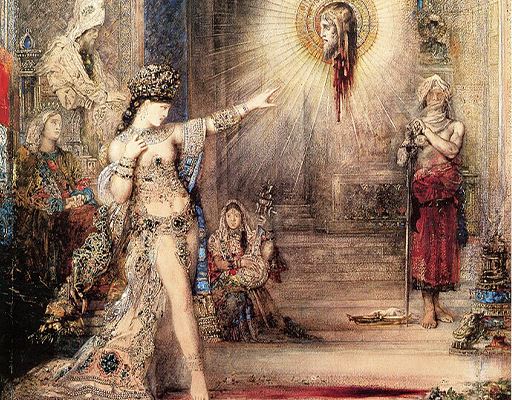

Gustave Moreau, Salome Dancing before Herod, 1876, oil on canvas, Armand Hammer Museum of Art, Los Angeles

The first pair of paintings that Des Esseintes presents in his collection, housed in his study on panels between bookcases, are both by Gustave Moreau, and share the same subject matter: Salome afore King Herod. The first of these pieces by the French artist is the oil painting Salome Dancing before Herod, 1876. In order to seduce her step-father into giving her whatever it is that she so desires, which happens to be the head of John the Baptist (at the behest of her mother), Salome dances as Herod sits enthroned in the background. Bedecked with jewels and holding a lotus stem aloft, Salome moves on pointed toes, head cast demure towards the flower-strewn floor, as her left arm is outstretched mid-dance. Herod’s eyes firmly follow Salome, belying the stoicism of his countenance. The piece exudes an intoxicating opulence, rich with burning incense, gilded lamps, and pillars, amidst the dulcet notes of a stringed instrument being played by a woman partly-disrobed.

Among all the artists he considered, there was one who sent him into raptures of delight, and that was Gustave Moreau. He had bought Moreau’s two masterpieces, and night after night he would stand dreaming in front of one of them, the picture of Salome.

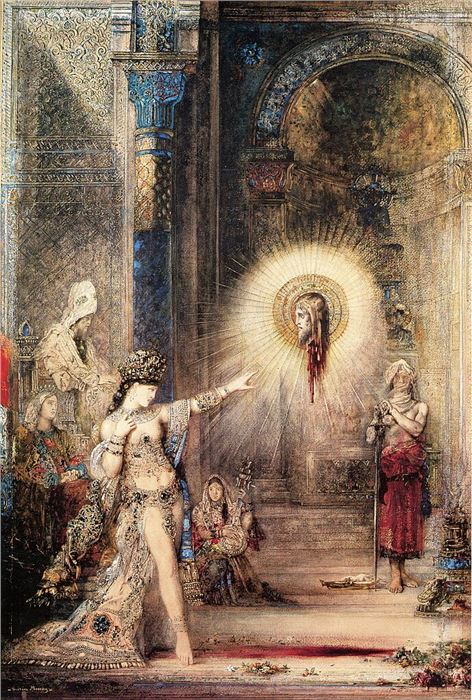

Gustave Moreau, The Apparition, 1876, water-color, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

The second piece by Moreau presents a decidedly different tableau in terms of mood and tone. Despite the fact that most of its key players remain unchanged, time has moved forward, and John the Baptist has now been beheaded. The flowers strewn across the throne-room floor are now surrounding a pool of blood, and Salome, in a strikingly similar pose as the previous painting, now outstretches her arm in revulsion against the severed head that hangs suspended above. Her eyes turned upwards towards the gruesome sight as if in a trance, while her tongue grotesquely starts to protrude from her mouth. She is not the demure daughter as she was before. She is now scantily clothed in jeweled gorgerin and girdle, with breasts and belly exposed. The lotus flower is nowhere to be found. Her innocence is gone, and the transformation is now complete. Herod sits enthroned once again, but struggles to keep his lecherous excitement as composed as before, leaning forward to gaze upon the gyrations of his now-salacious step-daughter as she writhes like a woman possessed. Salome’s mother, Herodias, sits beside Herod, a shell-shocked look upon her catatonic countenance as her left-hand claws against the balled fist of the right. Even the woman strumming the stringed instrument is noticeably disconcerted. It is a stark contrast compared to the previous painting, as evocative in its horror as the first’s tranquility.

Des Esseintes possessed a longtime obsession for the character of Salome, and felt that despite the fact that countless writers and artists had depicted her in their works, none had ever come close to accurately rendering her potent allure and tantalizing lasciviousness – even in the original Gospels – aside from the two pieces painted by Moreau. The heterogenous architecture that serves as a backdrop to the pieces, ensuring that place and time cannot be precisely pinpointed, enables Des Esseintes to be drawn into the paintings even further.

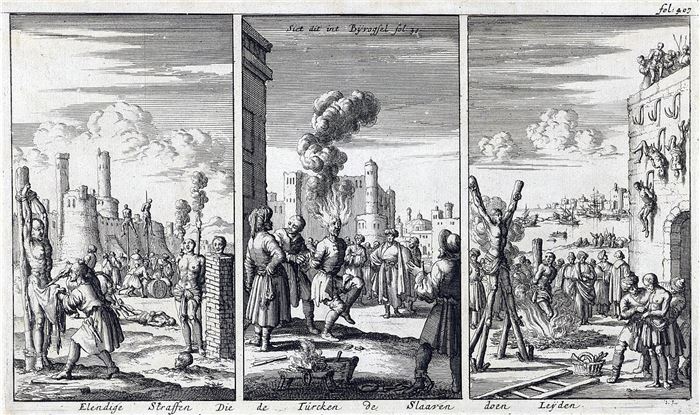

The next room in Des Esseintes’ sanctuary is the boudoir, its walls covered in bright red tapestry, on which are hung a series of ebony-framed prints by 17th-18th century Dutch engraver, Jan Luyken. Fanatically devout, Luyken would spend countless hours locked away writing and illustrating religious poetry, studying the Bible, and paraphrasing hymns. The series that Des Esseintes’ chose to proudly display upon the blood-colored walls is Luyken’s Religious Persecutions. A decidedly violent series that depicts all manner of utterly horrific ways that members of the Christian faith were tortured at the hands of others. Flesh flayed from the corporeal husk, acts of evisceration, bones broken, and other heinous acts of deliberately inflicted human suffering. The above etching is a quintessential example of the horrors depicted in Jan Luyken’s work.

These pictures, full of abominable fancies, reeking of burnt flesh, dripping with blood, echoing with screams and curses, made Des Esseintes’ flesh creep whenever he went into the red boudoir, and he remained rooted to the spot, choking with horror.

But Des Esseintes chose to hang the Dutchman’s work not merely for the visceral effect produced upon the viewer. The aesthete would also get lost in the backgrounds of the etchings, savoring the details found in the finely-executed crowds. He was also intensely attracted to the story of the artist’s life, one he undoubtably could relate to. The withdrawment from society that Jan Luyken undertook to create his pieces, the feverish and all-consuming manner in which he carried out his studies, and the final days of his life where he set out in a modest boat with his maidservant, preaching wherever they happened to come ashore, was of great fascination to him. The mundane is nowhere to be found in either Jan Luyken’s life or his work, and that is of the utmost importance to our anti-hero.

For more on auctions, exhibitions, and current trends, visit our Magazine Page