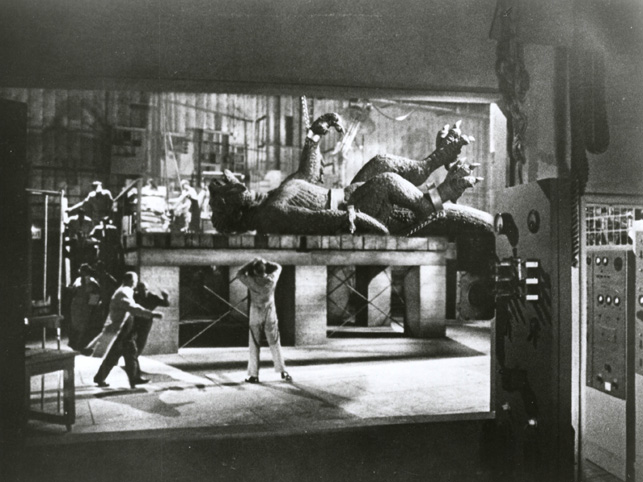

20 Million Miles to Earth. 1957. USA. Directed by Nathan Juran. Film Stills Archive, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

It was love at first sight for Tim Burton and stop-motion animation. At an early age, Burton was drawn to films such as Nathan Juran’s 20 Million Miles to Earth (1957) and Don Chaffey’s Jason and the Argonauts (1963), which featured innovative animation by special effects master Ray Harryhausen. Burton responded to the sense of wonder the technique conjured in its audiences and was inspired to create his own stop-motion animated films, such as a 1971 super-8mm short featuring cavemen and dinosaur figures (on view in the MoMA gallery exhibition) that invokes When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970, directed by Val Guest, and animated by Jim Danforth).

Later, as a student of animation at CalArts, Burton came to understand the artistry of the craft, and soon recognized that his attraction to the medium lay in its ability to lend gravity to the characters in films. The three-dimensional aspect of stop-motion animation made the fantastic characters appear more real. When watching 20 Million Miles to Earth, it’s hard not to feel for the put-upon “monster” who was transported to Earth from Venus through no act of its own. I certainly don’t fault its rampaging and rioting. The poor thing is probably just hungry and scared! The animation helped viewers identify with something that could not possibly exist.

Burton was compelled to utilize stop-motion animation because it could bring something purely imagined to vivid life in a way that 2-D animation couldn’t. For his first directorial endeavor as an apprentice animator at Disney, Burton chose to film Vincent (1982) using his beloved technique, because, according to early script notes (also on view in the exhibition), it had a “crude elegance,” and the articulated movements of the puppet reflected the “totally exposed feelings” of the Vincent Malloy character, a little bored suburban boy who dreams of being a tragic mad scientist. Burton grew up enamored of Universal horror movies such as James Whale’s Frankenstein (1931). Perhaps subconsciously, he gravitated toward a technique that could help him bring monsters to life.

In 1993, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare Before Christmas brought stop-motion animation back to the forefront of filmmaking. Its success proved that audiences would still respond to this age-old medium even in the face of new and wondrous computer-animated films. It perpetually amazes me to think about the process of creativity and the divergent paths it can take. Burton and John Lasseter were classmates at CalArts and colleagues in Disney’s animation department. From this similar start, while Lasseter was going to infinity and beyond with Toy Story (1995), the first completely computer-animated feature film, Burton went back to the roots with stop-motion animation, which is as old as film itself.

Popularly known as a live-action movie director, Burton never let go of stop-motion animation as his career blossomed, revisiting the medium with Corpse Bride (2005) and an upcoming remake of his 1984 short film Frankenweenie, this time as a feature-length stop-motion animated film. Even Burton’s original commercial for MoMA’s exhibition was made with stop-motion animation.

In conjunction with our Tim Burton retrospective, we are presenting a series of films that have influenced and inspired the filmmaker (including some of the films mentioned above). The series pays respect to some of the giants who have come before Burton in the field of stop-motion animation, and upon whose shoulders the filmmaker stands. As Burton was inspired by masters like Harryhausen (himself the subject of a MoMA retrospective—Ray Harryhausen: Special Effects (May 28–September 1, 1981)—who in turn had admired and trained under Willis O’Brien (creator of effects in King Kong [1933] and Mighty Joe Young [1949]), we wonder who among the new generations of filmmakers who fell in love with Burton’s stop-motion animated films will grace the walls of MoMA next.