Life Inside: California’s longest-serving Death Row prisoner

Editor’s Note: Douglas Ray Stankewitz has spent 43 years in San Quentin Prison for a crime he says he didn’t commit: the carjacking and murder of 21-year-old Theresa Graybeal in Fresno, California in 1978. In this interview, conducted in 15-minute phone calls, and edited and condensed for length and clarity, Stankewitz describes his life in prison – as an Indigenous man and as a Death Row prisoner for more than four decades.

This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletters, and follow them on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.

Douglas Ray Stankewitz

as told to Richard Arlin Walker

Special to Indian Country Today

In the 43 years that I’ve been trapped in a small cell at San Quentin, I’ve felt grass under my feet only five times. The first time was after I had spent seven years in the isolation unit because I refused to cut my hair. I’m Monache and Cherokee. They punished me despite the fact that it’s my tradition and spiritual belief as a Native American to grow my hair long.

But outside the isolation unit there was a row of grass that they really took care of. As the guards led me out of that building, I stepped off the concrete path so I could feel the grass and dirt under my feet. The smell of fresh-cut grass is still part of me.

Related stories:

—Indigenous man on Death Row maintains his innocence

—'She was a nice girl'

I'm sure most free people don’t even realize that they take something like that for granted, but it’s the little things that I cherish the most. I often think back to growing up at Big Sandy [Rancheria] — the coyotes and foxes, the geese and deer and wild turkeys. There were 17 of us living together in three cabins, and it only cost about $80 a month to feed us. We ate venison, rabbit and turkey, and we had a garden. We always had homemade biscuits, tortillas, frybread and cornbread, and there were always beans cooking on the back of the potbellied stove. Those thoughts, along with the discipline I’ve developed in here, have helped sustain me.

I can say that conditions in the isolation unit have changed since 1980, when I was there for the first time. Back then there was a hole in the floor for a toilet. The toilets were supposed to be flushed once every 24 hours, but they rarely were. My eyes burned from the feces eating the paint on the wall.

SUPPORT INDIGENOUS JOURNALISM. CONTRIBUTE TODAY.

We were supposed to get 1,500 calories a day. But we got one meatball in the morning and one at night with half a slice of bread. Anytime people acted up, the guards would pepper-spray them. Sometimes, guards would spray people just to see how they’d react.

Guards would also take our mattresses in the morning and give them back at night — presumably because they didn’t want inmates destroying them. But nine times out of 10 you wouldn’t get your mattress back. It would be someone else’s, and there might be feces on it or urine on it. After five times, I told them, “No, I don’t want a mattress anymore.” I haven’t had one since then. I just fold a blanket in half and sleep on it. I also haven’t had a pillow — I use a roll of toilet paper, and I’m comfortable with that.

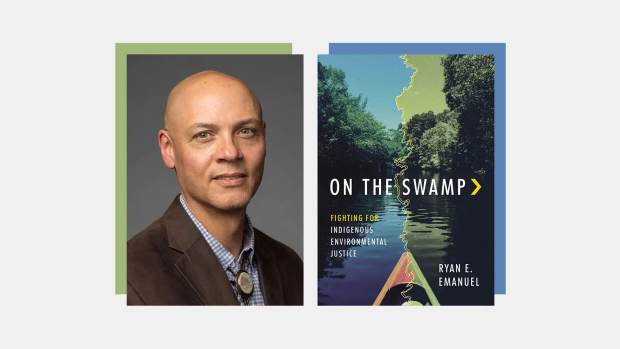

Douglas Ray Stankewitz, 64, Monache, believed to be the longest-serving inmate on San Quentin Prison's Death Row, continues to fight his conviction in the 1978 slaying of 21-year-old Theresa Graybeal. He originally received the death penalty but his sentence was later reduced to life in prison. (Photo courtesy of the California Department of Corrections)

Read More

In the Death Row cells where I’ve spent most of my time, I’m still in isolation — it’s just not as bad. My current cell is roughly 4 1/2 feet by 10 feet. Along with my toilet, bed and sink, I’ve got a shelf, two lights and a typewriter. I have some CDs and a CD player with a radio. I also have some photos and eight posters of Harley Davidsons. My dad was a biker.

But I’m still locked up all the time, and I don’t come out unless I’m handcuffed. I go to the shower, I’m handcuffed. I go to medical or the yard, I’m handcuffed. A guard is always watching. It’s like I’m in a zoo.

We do have Native worship services at San Quentin, but our religious adviser doesn’t do it right. He has a sacred pipe that he allows everybody to touch, and that’s bad medicine. You’re not supposed to touch the pipe or anything sacred like that if you have blood on your hands. If you’ve killed someone in self-defense or to protect your family or your property, that’s one thing. But if you kill somebody just to kill, it’s called having blood on your hands. That’s why I go to other worship services to absorb other teachings and learn about different religions.

We used to have four powwows a year. Tribes from the Bay Area and all the way up north would offer buffalo, elk, venison and fish. Now we’re lucky if we have one powwow every three years. The spiritual advisor would tell the tribes that we were going to have a powwow on a certain date, and after the tribes caught fish and deer for it, he’d say, “Well, now we’re going to have it next month.” You can’t do that.

When we did have a powwow, we’d get a two-ounce serving of salmon and everything else would be prison food. The prison wouldn’t allow people to bring in buffalo meat because they said bones were a security risk. They could just take the meat off the bone and then bring it in, but they won’t do that. You’ve got these brothers and sisters in the free world going out and getting it for us, and we can’t have it.

Meanwhile, my daily routine is the same as it has been for decades. I wash up, make sure my cell is clean, then I say my prayers and I meditate for 20 minutes to an hour. After that, I turn on the radio, exercise, maybe type a letter and get my breakfast. I work on my case for about three hours a day. We have a law library, but you have to get on a list so you might go once a month. Every week we can put in requests for a law book we need. You may be placed on a waiting list for the book, but it's better than nothing.

I go to the yard with other people twice a week for a total of six hours — unless it’s foggy or there’s been an incident and we’re in lockdown. I get to shower for 15 minutes every other day with a guard standing by. Otherwise I’m in my cell.

Since my sentence was reduced to life without possibility of parole, I have the option of transferring to a cell in the general population. But I’d have to go to a Level 4 maximum security unit where there’s a lot of violence. Other inmates would want to test me because I’ve been on Death Row. I also have the option of moving to a different prison, but my legal team is in this area. I might end up 500 miles away; that would make it harder for them to come and see me when they have to.

As I await a court date, I try to be the best person I can be so I can go to sleep at night and say, “Well, I did a good day. I didn’t do anybody wrong, I didn’t lie to anybody.”

People have asked me, “How did you make it through [nearly 44] years in prison?” And I say, “By being Native.” Being Native gives me the strength to overcome all of this — not just for me, but for all our brothers and sisters. Society cannot break our spirit.

Our stories are worth telling. Our stories are worth sharing. Our stories are worth your support. Contribute $5 or $10 today to help Indian Country Today carry out its critical mission. Sign up for ICT’s free newsletter.