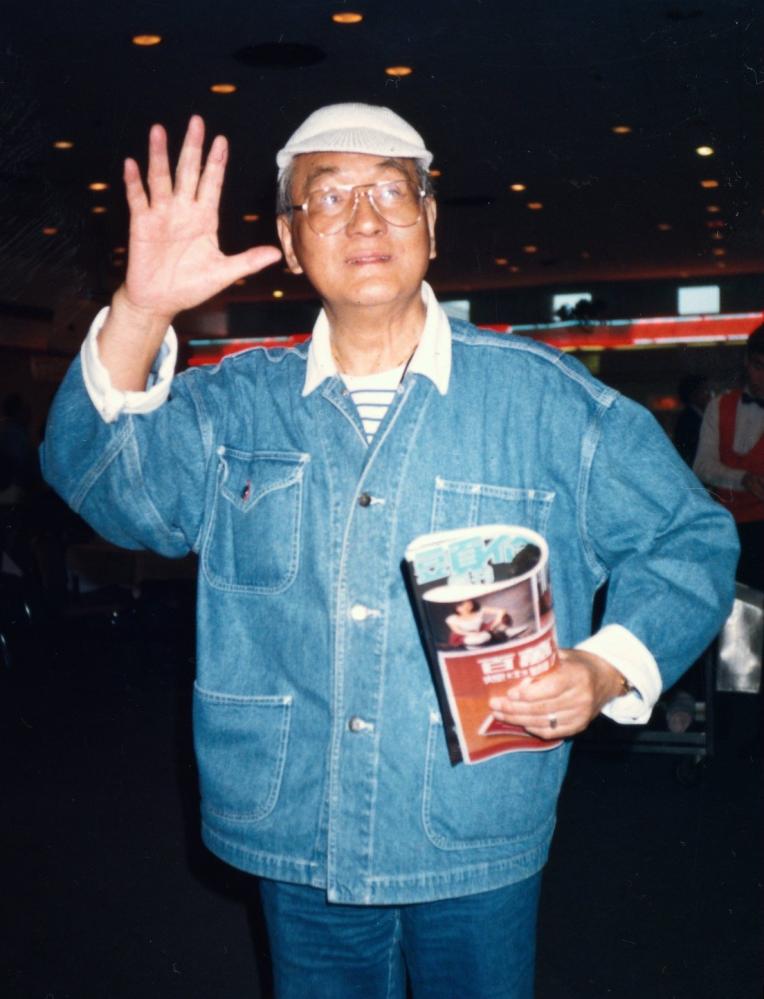

He trained Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao, but who was martial arts master Yu Jim-yuen, the forgotten ‘godfather’ of Hong Kong kung fu cinema?

Despite their different looks and specialities all three were trained by the same man at the same time, at least for a few years. That man was Yu Jim-yuen. Not only did Yu train the “Three Dragons”, he also guided other important figures in the local film industry like Corey Yuen, Yuen Wah, Yuen Tai, Yuen Miu and Yuen Bun – all of whom took his name to honour him.

Does Bruce Lee’s legacy have a dark side?

Given his outsize influence on Hong Kong and martial arts cinema, Yu is something of a forgotten figure. He supposedly trained his charges at Kowloon’s China Drama Academy but records are spotty about the establishment’s actual name or location. The South China Morning Post’s brief obituary for Yu refers to his school as the “Chinese Opera Research Institute” and describes it as being on the rooftop of Mirador Mansion in Tsim Sha Tsui. Another website erroneously places the school in Lai Chi Kok, probably mistaking its location for that of Lai Yuen Amusement Park where Chan and his schoolmates would sometimes perform.

Are old Hong Kong’s famous tailors disappearing?

Chan recollects his first visit to his future sifu in his autobiography, I Am Jackie Chan: “We pushed our way down to Nathan Road ... and then down a maze of side streets. Finally, one last turn brought us into a street lined with tenements whose windows were dark and shuttered. The sign before us proclaimed the building we were about to enter as the China Drama Academy, a name that told me nothing.” The future star goes on to describe a small courtyard and rooms beyond that – nothing like what one imagines existed on the roof of Mirador Mansion, assuming the Post’s account is accurate.

Whatever the origins of Yu’s academy, its master’s training regime has become legend for its severity. Born in Beijing in 1903, Yu moved to Hong Kong sometime in the 1950s, well-versed in the art of Peking opera and the fierce discipline traditionally required of students of the art.

To some, conditions at the China Drama Academy were “Dickensian”. Jackie Chan spent 10 years under Yu’s tutelage, eventually becoming his godson when his biological parents emigrated to Australia. Despite such a seemingly close relationship, Chan’s account of his time with Yu is far from flattering.

“Master believed in just three things: discipline, hard work and order,” Chan wrote. “Discipline came quickly and painfully, measured in strokes of the cane. Hard work was the rule of the day – a few minutes of stolen rest often meant an hour of extra practice for any unlucky students caught slacking off. And order: order was imposed by a strict line of command that placed Master at the top (never to be disobeyed or disrespected).

Olivia Liang talks new series Kung Fu

“The order was never to be challenged. If a brother who was more senior told you to do something, you did it. If you told a more junior brother to do something, he did it. And if Master gave a command, everybody jumped. The order was enforced by the fact that anyone who disobeyed it was beaten soundly, either by the master’s cane or, among students, by the simpler (but not any less painful!) means of a hard-swung fist.”

By all accounts Yu was a tough task master, near impossible to impress. He would pick holes in everything. If it wasn’t a student’s execution of moves that was poor, it was in the style. If it wasn’t the style, it was in the energy. If it wasn’t the energy, it was the attitude. And every mistake led to some form of physical punishment.

It was a harsh existence, even if graduates like Hung and Chan joke it about these days.

All Yu’s famous graduates credit him with helping them become a star. There are still opera schools training kids but, obviously, Yu’s style of training has fallen out of favour. For his part, Chan seems to have mixed feelings about this development: “That kind of discipline is now against the law. But to tell the truth, younger generations of performers aren’t as good as we were and the ones who went before us ... So I guess you could say the system worked.”

Chan admits there wasn’t a day that went by that he didn’t think of running away from Yu’s school, and that he might have done so had he anywhere else to go. Nonetheless, he has said of his biological father that while “Charles Chan was the father of [his Chinese name] Chan Kong-sang, Yu Jim-yuen was the father of Jackie Chan”.

Smashing it: style moves from kung fu master Bruce Lee

Upon his parents’ emigration, Yu became a literal father-figure to the future martial arts star. Yu apparently had reservations about adopting Chan as his godson, due to his mischievous behaviour, but accepted sensing the boy’s potential. Not that this made life easier for Chan – Yu expected his “son” to set an example and train twice as hard as other students.

Unfortunately, as Chan and his brothers and sisters reached adulthood, opera was a dying art form. It had gone from being a pillar of Chinese culture to a quaint traditional art appreciated only by a few connoisseurs and members of older generations. And as Hong Kong rapidly developed in the 1960s and 70s, opera was left behind and the China Drama Academy’s training regime appeared increasingly anachronistic.

The old paying gigs that Yu had relied on – performances at weddings, festivals and Lai Yuen Amusement Park – were all drying up. The only option left for these talented martial arts practitioners was the burgeoning movie industry. Increasingly, Yu lent students like Chan out to film studios as extras. Initially Yu gave his “Seven Little Fortunes”, as his top students like Chan were known, just HK$5 out of every HK$75 they earned for their bit parts. As the children grew older, though, they wrangled more out of their imposing teacher.

A trend had been set, and Yu’s students increasingly looked to spread their wings. By this time, Chan and his older brothers had become regulars at Shaw Brothers and other film studios working as junior stuntmen. But as more experienced opera trainers began to enter the movie industry, so competition for roles increased. It was this fact that eventually forced the likes of Jackie Chan to strike out on their own and leave Yu behind.

Why Bruce Lee might really be the ‘father of MMA’

Chan recalled: “I’d spent a decade with this man, this distant and domineering figure, and never received more kindness than a dry smile or a pat on the head ... I felt no pain, and had no tears at our parting. But still, this stiff ending, this hollow goodbye – it somehow left me feeling a deep and unquenchable sense of loss.”

With his business winding down Yu eventually moved to America with most of his family. His daughter, Yu So-chau, stayed behind and became a star of Cantonese cinema in her own right. Yu Jim-yuen continued to teach martial arts and opera in the US, albeit without the same severity bestowed on the likes of Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung and Yuen Biao.

Eventually Yu succumbed to Alzheimer’s, passing away in September 1997. Chan, Hung and Biao were all among their master’s pall bearers.

5 Asian actresses who made it in Hollywood, from Bae Doona to Maggie Q

Although he may not have a place on Hong Kong’s Avenue of Stars, Yu left behind one of the most impressive legacies of any figure in Asian cinema. In training the “Three Dragons”, he was indirectly responsible for some of the greatest Hong Kong and martial arts films of all time. As his most famous student concluded, “It could be said that Master Yu wasn’t just my godfather, but one of the godfathers of the Cantonese movie industry. Not a bad legacy, wouldn’t you say?”

Want more stories like this? Sign up here. Follow STYLE on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Twitter.

- The ‘Three Dragons’ or ‘Three Brothers’ made some of the most popular kung fu films of Hong Kong cinema’s golden age, including Project A and Wheels on Meals

- After enduring the tough love of Yu’s China Drama Academy the trio went on to find fame, first as stuntmen with the legendary Shaw Brothers film studio