November 25th, 2020: the New York Times draws up a list of the greatest actors of the 21st century. The only Italian, ranking seventh, is Toni Servillo. According to their reasoning, the actor had been “the central avatar in Sorrentino’s excavation of the corruption and hypocrisy, but also of the improbable glory and absurd resilience of modern Italy.” Above all, what was praised was his ability to embody two extremely different political leaders–Giulio Andreotti in the scabrous and satirical Il Divo, and Silvio Berlusconi in the epic and weirdly tender Loro. Like a Shakespearean actor, Servillo has been perfectly able to capture all the facets of real and imaginary characters, drawing on his long experience as a theater director and actor. His voice, his gaze, his eloquence, his charm, his credibility in every role are all elements that make him one of the most coveted contemporary Italian actors. His ability to enter the world of his characters with an extraordinary camouflage is the reason why he’s been masterfully selected to play many real-life personalities.

We didn’t have enough room to list all his iconic roles on the big screen, so we’ve decided to focus attention instead on his interpretations of five real Italian characters of the 20th century–both to give visibility to lesser-known titles (compared to the Oscar winner La Grande Bellezza or the Oscar nominee È stata la mano di Dio) and to celebrate his ability to overcome the mammoth challenge of accurately portraying complex, nonfictional characters.

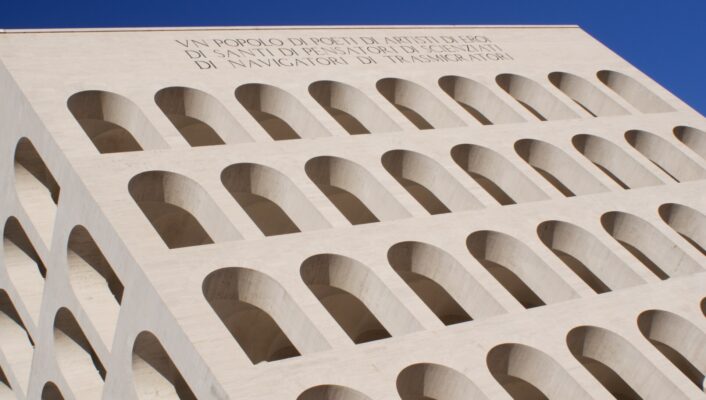

Rome where La Grande Bellezza was filmed

1. Eduardo Scarpetta (Naples, 1853-1925)

Qui rido io (2021) by Mario Martone

Toni Servillo pays tribute to Eduardo Scarpetta–probably the most important Neapolitan stage actor between the 19th and 20th centuries–masterfully in Qui rido io by Mario Martone, a director with whom Servillo has a privileged relationship both in theater and cinema. The film follows Scarpetta, an amoral patriarch, progenitor of a family of actors and actresses; Eduardo, Peppino and Titina De Filippo, some of his illegitimate children, inherit an invaluable creative heritage, and they take their first steps in theater right next to Scarpetta. The biographical movie, internationally known as The King of Laughter, narrates the success and the decline of this charismatic playwright, whose greatness could be potentially compromised by a legal battle against the poet and playwright Gabriele D’Annunzio over his parody of D’Annunzio’s “La figlia di Iorio” (1904). Thanks to the character of the soon-to-be Eduardo De Filippo, Qui rido io narrates the passage from the traditional pure entertainment theater to a more sophisticated and contemporary conception of this form of art.

“I imagined Scarpetta as an animal. Animals prey by nature, but they don’t prey randomly: they trace a limit within which they decide to hunt. His prey were the women, the theater, the cities, the theater tours, the texts, in an extraordinary exchange of life and stage. This fresco shows us to what extent life is made of theater and how much theater is in life.” With these words Servillo summarizes the essence of his interpretation–both narrator (and somehow author) of a character, creating a fascinating meta-theatrical mechanism. Scarpetta (Servillo) declares: “A forza mia è ‘o pubblico” (literally “my strength is the audience”).

Photography by Gina Spinelli

2. Luigi Pirandello (Agrigento, 1867 – Rome, 1936)

La stranezza (2022) by Roberto Andò

In La Stranezza (literally “strangeness”), Servillo moved towards more popular cinema by playing another fundamental Italian playwright: Luigi Pirandello. In the film, Pirandello is in Sicily to celebrate Giovanni Verga’s 80th birthday, but he perceives a so-called “strangeness” within himself. His strangeness is an inexplicable form of creative crisis in which his own characters begin to populate his days. Here again, the spaces of life and theater intersect and merge. This “strangeness” will generate Six Characters in Search of an Author, one of the most revolutionary works in the history of global theater and one of the most representative of Pirandello’s production. Similarly to the Pirandellian “absurd” masterpiece about the relationship among authors, characters and theater practitioners, La Stranezza is a fantasy about repercussions of creativity and inspiration: the film is a journey suspended between the writer’s real life and his fantastic inventions.

“In a year and a half, I would have never imagined making two films about the theater with two directors dear to me, who are men of theater too. Qui rido io and La Stranezza are two different films that go far beyond being a tribute to the theatrical world. They speak about the joy of life, and they celebrate life in all its aspects.” In this film, Servillo’s ability to show the man behind the artist is masterful: Pirandello appears a restless, fragile man who used to listen to popular sensibilities–far from the typical, monumental image of a shy and detached writer. In the movie, we can see the playwright participating in the social life of Girgenti, and having hilarious conversations about the world of theater with Nofrio and Bastiano, two amateur actors played by the comic Italian duo Ficarra e Picone. It won’t be misleading to affirm that putting Toni Servillo and Ficarra e Picone together in the same film has been an attempt to reconcile the character of Pirandello (and Servillo himself) with a more popular awareness (it has been the highest performing Italian title at the Italian box office in 2022, a totally unexpected result).

The director Roberto Andò defines La Stranezza as a film for an “audience in search of an author”: through Servillo’s eyes and gestures, we can actually restore vitality and humanity to a crucial author in Italian literature.

3. Pope Paul VI (Concesio, 1897 – Castel Gandolfo, 1978)

Esterno Notte (2022) by Marco Bellocchio

After the theatrical characters, Servillo enters the papal rooms of St. Peter’s through Cardinal Montini, Pope Paul VI. The director of the film is, once again, a great master of Italian cinema: Marco Bellocchio (the lineup of directors Servillo has worked with is an all-star list). Here the director, after the movie Buongiorno, notte (2003), extends his commentary on the kidnapping of Aldo Moro, leader of Democrazia Cristiana (literally “Christian Democracy”).

Once it’s clear that a “political way” is not effective, Paul VI, both as the Pope and as a friend of Aldo Moro, attempts a “Vatican way” for the release of the politician, who was instead found dead on May 9th, 1978.

Unlike in the aforementioned films, Servillo has the task of restoring credibility to a character who television has seen in action, and who is still remembered by some. However, we once again watch the “behind-the-scenes” of a prominent figure of the 20th century–this time on both a political and ecclesiastical stage. In Servillo’s lost gaze, we find a man who suffers the public nature of his job: Pope Paul VI can’t just be a person, he has to be an actor himself. This Paul VI is a man who faces a personal Via Crucis in fighting to save his friend. When Moro was kidnapped, Paul VI was already fighting troubled breathing and mobility difficulties. Nobody will ever know if Moro’s death could have worsened his health, but he died just three months after Moro from a pulmonary edema at the age of 80.

As Servillo notes, “Paul VI recalls important figures in drama: he must bear the conflict between a sense of responsibility and mercy.” In meetings, the religious leader appears imperturbable, but he mourns in private the torment of solitude as well as the awareness of not being supported by political forces (especially Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti, who Servillo has also played). With few words, an on-point portrayal of the affliction of old age and powerful determination, Servillo portrays the Pope’s extreme difficulty in reaching people who are very far from him, and in finding the right language to talk to their hearts.

Castel Gandolfo

4. Giulio Andreotti (Rome, 1919 – 2013)

Il Divo (2008) by Paolo Sorrentino

“A cold, impenetrable director, without doubts, without flutters, without a moment of human pity. Indifferent, livid, absent, closed in his dark dream of glory. He conquered the power to do evil, as he has always done evil in his life.” These are the harsh words, taken from Aldo Moro’s memoirs, on Giulio Andreotti, Prime Minister at the time of his kidnapping and protagonist of Paolo Sorrentino’s masterpiece Il Divo, an eye-catching movie about a sober and shady man. Andreotti once said to Pope John XXIII, Paul VI’s predecessor: “Sorry, Your Holiness, but you don’t know the Vatican.” It is unknown the circumstance in which he said this, but the “legend” conveys how the politician is still surrounded by an aura of mystery.

Thanks to the Cannes première, this is most likely the role that made Servillo an international star, even before Sorrentino’s The Great Beauty (2013). Servillo embodies, with his mimetic strength, his transfigured face, his jerky movements and his almost identical voice, the fluctuating nature of his character. Andreotti is portrayed as a bidimensional man in black and white, who weaves the web behind almost every important Italian event of the second half of the 20th century. Although involved in countless legal charges, including the “Trial of the Century” in which he was accused of collaborating with the mafia, Andreotti never faced the consequences in his political career and became Prime Minister seven times.

The journalist Indro Montanelli will say about him: “Either you are the most cunning criminal in this country, because you have always gotten away with it; or else you are the most persecuted person in the history of Italy.” In Servillo’s highly expressive face, all this contradiction is shown, perfectly manifesting the aura of a Mephistophelean character. Servillo is Andreotti to such an extent that one is almost tempted to reach out to him and extract all the confessions to which the politician resisted until his death.

5. Silvio Berlusconi (Milan, 1936 – )

Loro (2018) by Paolo Sorrentino

“Before this film, I had the good fortune to make Il Divo with Paolo, and therefore I could compare one with the other, given that here it was again about playing a real character, as well as a controversial politician. Andreotti was an introverted and secret character, who moved almost exclusively in political institutions. Berlusconi, on the other hand, is the opposite: an extroverted star, who obsessively occupies, with his presence, the interiority of those who desperately try to imitate the model without succeeding,” said Servillo.

The film goes back to 2007, when the histrionic Berlusconi was defeated at political elections by a handful of votes and was planning his return to places of power from his Sardinian Villa, a sort of Eden-mausoleum. To do so, he had to convince six senators, not belonging to his political coalition, to betray the left-wing government and to sustain him. It is not a coincidence that, in an amazing scene in which he has to test if his persuasive verbal power is still brilliant, the protagonist proudly declares: “I know the script of life.” As paradoxical as it may seem, Servillo’s interpretation is more easily comparable to that of Scarpetta than of Andreotti: Berlusconi comes across as a very good actor waiting for his triumphant return on stage.

Assuming that everything has already been said about Berlusconi, Sorrentino investigates the politician’s deepest fears of aging, dying and lack of immortality. Silvio is a buffoonish character who is expected to be the richest man in Italy, Prime Minister, and to be loved by everyone. As he did with Andreotti, Servillo is here able to imitate his voice and his facial movements and to return the hedonistic spirit of this unfortunately charismatic man. At the same time, he complicates the public image of Berlusconi: in one intense conversation with his former wife Veronica Lario (Elena Sofia Ricci), he seems to be an eternal Peter Pan, incapable of taking personal and public crises seriously.

The fate of the film, which has now all but disappeared, is also a very Italian story: already absent on streaming platforms, the movie has never been released in an Italian home-video edition. Consider that, during the film, Berlusconi’s former wife Veronica Lario tells the politician: “You were never interested in Italians: you were always interested only in yourself. When you were in office, you sold off culture, people’s hopes, and women’s dignity. You are just a very long and uninterrupted staging.” Can you guess who had an interest in making this movie disappear?