Welcome to the Archives of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture. The purpose of this online collection is to function as a tool for scholars, students, architects, preservationists, journalists and other interested parties. The archive consists of photographs, slides, articles and publications from Rudolph’s lifetime; physical drawings and models; personal photos and memorabilia; and contemporary photographs and articles.

Some of the materials are in the public domain, some are offered under Creative Commons, and some are owned by others, including the Paul Rudolph Estate. Please speak with a representative of The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture before using any drawings or photos in the Archives. In all cases, the researcher shall determine how to appropriately publish or otherwise distribute the materials found in this collection, while maintaining appropriate protection of the applicable intellectual property rights.

In his will, Paul Rudolph gave his Architectural Archives (including drawings, plans, renderings, blueprints, models and other materials prepared in connection with his professional practice of architecture) to the Library of Congress Trust Fund following his death in 1997. A Stipulation of Settlement, signed on June 6, 2001 between the Paul Rudolph Estate and the Library of Congress Trust Fund, resulted in the transfer of those items to the Library of Congress among the Architectural Archives, that the Library of Congress determined suitable for its collections. The intellectual property rights of items transferred to the Library of Congress are in the public domain. The usage of the Paul M. Rudolph Archive at the Library of Congress and any intellectual property rights are governed by the Library of Congress Rights and Permissions.

However, the Library of Congress has not received the entirety of the Paul Rudolph architectural works, and therefore ownership and intellectual property rights of any materials that were not selected by the Library of Congress may not be in the public domain and may belong to the Paul Rudolph Estate.

LOCATION

Address: 180 York Street

City: New Haven

State: Connecticut

Zip Code: 06511

Nation: United States

STATUS

Type: Academic

Status: Built; Addition

TECHNICAL DATA

Date(s): 1958-1964

Site Area:

Floor Area: 117,575 s.f.

Height: 86’-8” (26.41 m)

Floors (Above Ground): 7

Building Cost: Original Building: $3,052,782 ($25.96 per s.f.); Original Furniture & Equipment: $140,854

PROFESSIONAL TEAM

Client: Yale University

Architect: Paul Rudolph

Rudolph Staff: Bill Bedford

Associate Architect:

Landscape:

Structural: Henry A. Pfisterer

MEP: Van Zelm, Heywood & Shadford

QS/PM:

SUPPLIERS

Contractor: George B. H. Macomber Company; Charles Solomon, Partner-in-Charge

Subcontractor(s):

art & Architecture Building for Yale University

The project for the Art & Architecture building is originally created by the need to make room for other buildings at Yale. No provision for the building is made for it in the master plan drawn by Eero Saarinen or Douglas Orr in 1956 and later reaffirmed in July 1957.

In the Spring of 1957 President Griswold encourages newly appointed Art Gallery Director Andrew C. Ritchie to plan museum expansion into the area of the new wing that was set aside for the school, then known as the School of Architecture and Design.

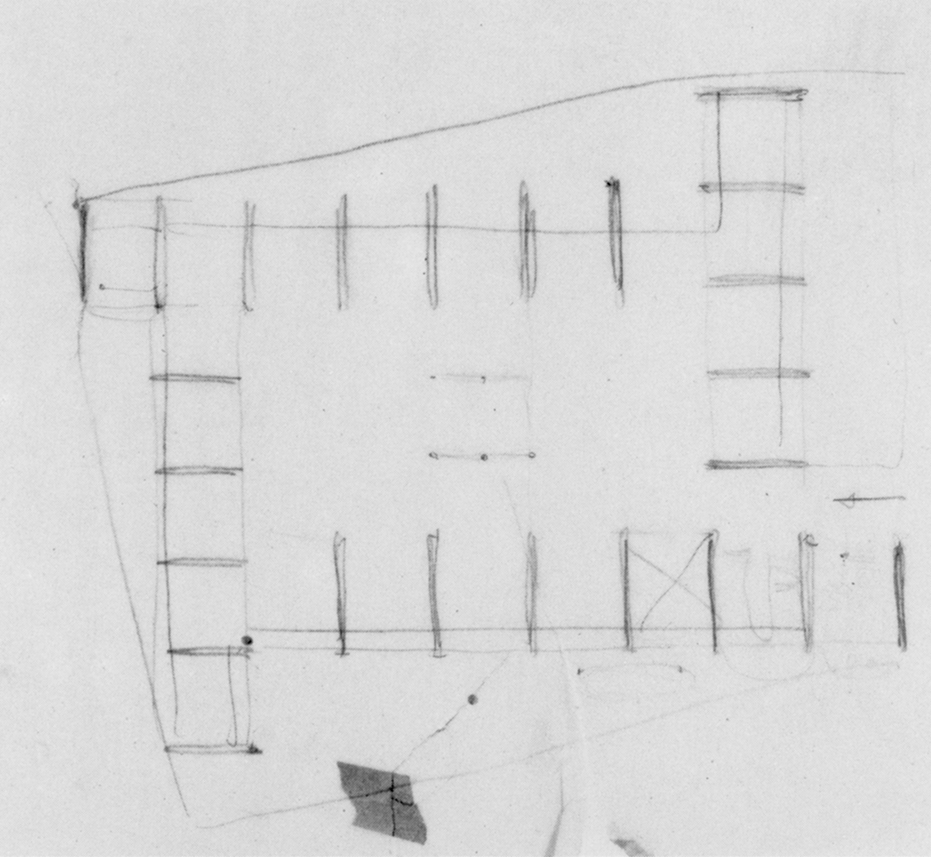

By June 1957 there is discussion of building a wing between the Art Gallery and Weir Hall and Rudolph suggests to Griswold that it be built as a bridge to spare the courtyard. But this wasn’t enough, and in early February 1958 Ritchie proposes that Weir Hall be torn down for a new building. By the end of the month it is agreed that Street Hall will be demolished, and Rudolph makes preliminary sketches for a new building on this site.

Although rumored, it is not true that Rudolph came to Yale on the promise of designing the new Art & Architecture building. Rudolph is appointed chairman of the department of architecture in June 1957. He suggests the commission go to Le Corbusier, but the Yale Corporation decides against an absentee architect for the project. Vincent Scully claims Rudolph recommends Louis Kahn, but Rudolph later denies this. Ultimately, Griswold decides to give the commission to Rudolph.

By April 1958, Rudolph draws preliminary budgets and space allocations for a long narrow site running back over part of Linsly-Chittenden Hall. He prepares two budgets - one for a building of 103,000 s.f. and no library, the other for 123,000 s.f. and a library of 70,000 volumes for the art history department. The latter is expected to cost $4,600,000.

These two options (with and without a library) alternate in favor during the next few years, depending upon the prospect to raise the necessary funds. Costs and dimensions of the building design change little, but space distribution varies over the course of design.

Rudolph, relying on briefs and consultations with Dean Gibson Danes and department chairmen and using a survey of existing areas, calculates 16,000 s.f. of work space for 166 students of architecture and city planning and 26,600 s.f. for 150 students of painting, sculpture and graphic arts with 7,800 s.f. for jury and exhibition areas.

A fully developed program is delayed by lack of money until the winter of 1958, when Rudolph prepares a model which is described in the December 8th issue of the Yale Daily News.

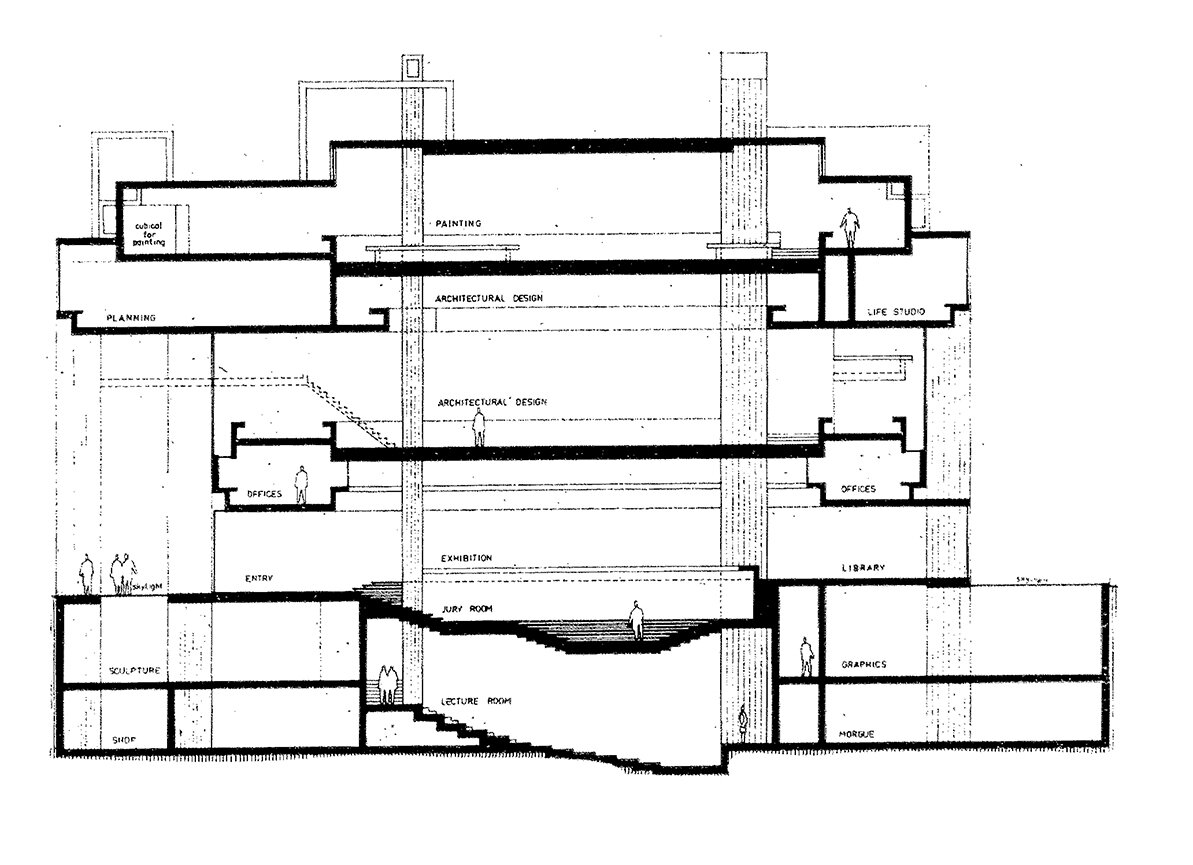

According to the article, there are to be two lower levels for graphic arts and sculpture, lit through a dry moat; a first floor for the exhibition and jury room so that ‘the students and faculty could have a chance to view the art and architecture projects on their way to other parts of the campus.’ The second floor will ‘probably’ be for offices and classrooms, the third for architectural design, the fourth for advanced painters, architects and city planners so that ‘they can maintain close daily contact with each other.’ The fifth and sixth floors are for painting and studios. The interior will probably have a ‘shaft of light through the middle of the building, opening to most of the floors.’ The article says the building’s exterior will be of masonry ‘to blend with the building’s surroundings’ which are Neo-Medieval.

In May 1958 it is proposed that the site be moved to the northwest corner of York and Chapel Streets, on a lot occupied by a gas station. The Yale Corporation is asked to confirm the Street Hall site in April 1959, but does not. Rudolph submits two plot plans for the York Street site on May 15th 1959 and a budget by the end of the same month. The new site is finally agreed at the end of May 1959.

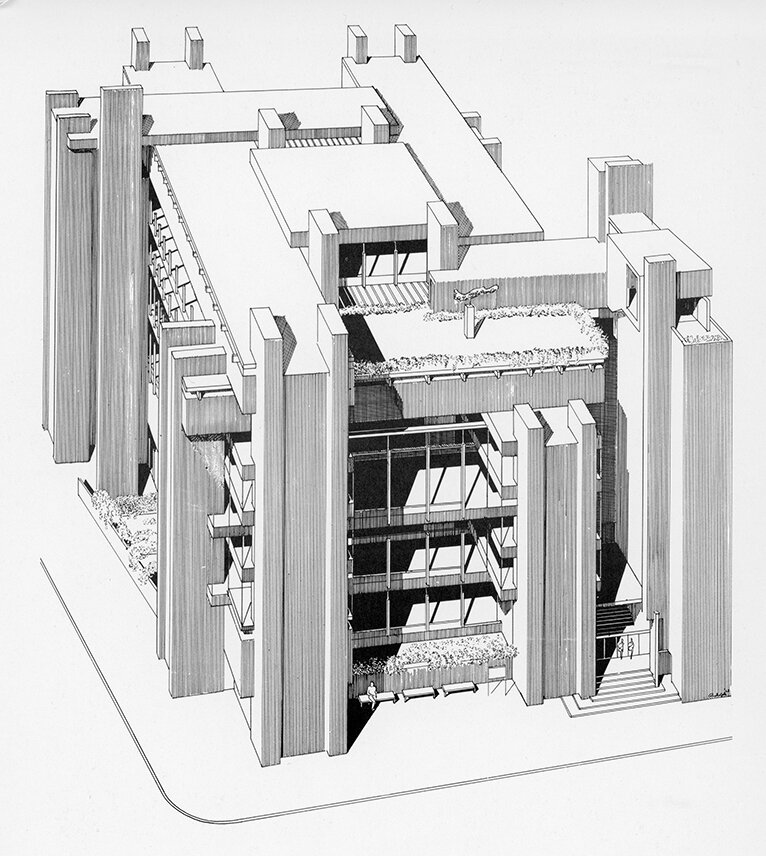

By December 1959 Rudolph alters the original horizontal scheme he produced for the Street Hall site to fit the news site. The plan is nearly square with floors pinwheeling around a core of double height rooms. The height above the grade is reduced to five and a half stories, with the stairs and elevators pulled out into towers so that the building can be extended to the north in the future. Administrator Norman S. Buck calls it a ‘very masterful and careful job of analysis.’

The Yale Corporation approves the interior layout on January 9th 1960, but asks for alternatives for ‘the roof and the outside of the top two floors.’

Rudolph relocates the entrance from the Chapel Street corner to the north circulation tower with a ramp. The design is approved by the building committees and then by the Yale Corporation on May 14th 1960 and Rudolph is told to proceed with working drawings.

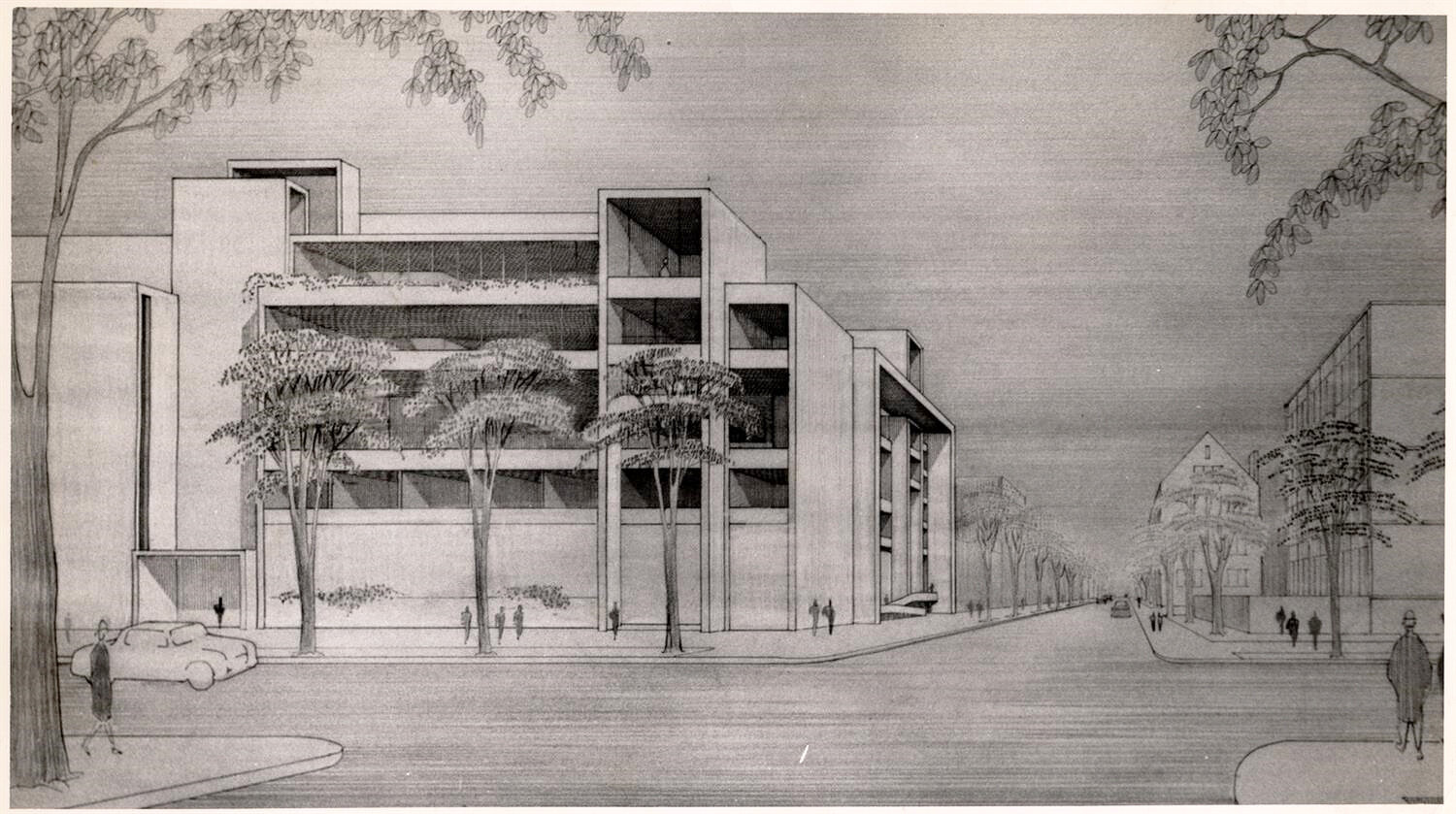

On June 18th 1960 the New York Times publishes a rendering of the proposed building. Members of the Yale Corporation reach out to the President noting the design is different from the rendering approved by the Corporation. While the interior of the project remains, the exterior of the new rendering has a scored surface which is described as ‘bush-hammered.’ The inspiration for the new rendering is from a trip Rudolph took to visit Chandigarh a few weeks earlier.

After receiving criticism from the Yale Corporation, Rudolph revises the new exterior design by extending the style of the exterior facade to the building as a whole. Rudolph prepares a revised model which is approved on November 4th 1960. By December 8th and 9th several Corporation members have reservations about the new model and after Rudolph meets with them it is voted to recommend acceptance of the new design.

On February 11th 1961 the library is incorporated into the project and a revised design is approved on April 8th 1961.

Yale acquires the gas station property in May 1961.

Rudolph meets with Griswold in the autumn of 1961 and gets approval for the design of the concrete ribs and the final ‘bush-hammered’ finish.

The final design has 36 different levels and is nominally nine stories in height.

Ground is broken for the project on December 09, 1961

Paul Rudolph’s office produces over 1,000 drawings for the project between 1959 and 1963.

The building is dedicated on Saturday, November 09, 1963.

In conjunction with the opening, the Yale Art Gallery across the street shows the painting of Jack Tworkov along with enlarged photos, drawings and models of other projects by Paul Rudolph.

The window hangings in the building are made from cargo rope made in India.

An original Louis Sullivan door made for the Garrick Theater in Chicago is installed inside the building. Also casts of friezes from the Parthenon as well as friezes by Donatello, Della Robbia and Louis Sullivan are mounted on the concrete walls throughout the building. Rudolph finds as he mounts these sculptures that they were all from three feet, two inches to three feet, four inches in height making them practically identical in size regardless of the different periods in which they were created. Rudolph obtains these casts from the University’s basements where they were in storage having been used previously in instructing art students.

In July 14, 1969 a fire breaks out in the drafting room which causes superficial damage to the upper floors of the building. The cause is not determined, but there are several theories including students who are upset with the overall design of the building.

Repairs and alterations are made to the building in the Spring of 1971 by a New Haven firm including new lighting and sunshades on the fire damaged floors, and a reconstruction of the drafting room for the painters.

The building and the 1969 fire are the subject of an exhibition “Architecture or Revolution: Charles Moore and Yale in the late 1960’s” held at the Yale University School of Architecture Gallery from October 29, 2001 until February 01, 2002. The exhibition is curated by Eve Blau.

In 2008 an addition is constructed along with a renovation and interior restoration of the existing building, undertaken with the support of Sid R. Bass.

The building is rededicated and officially renamed ‘Rudolph Hall’ on November 7, 2008.

The original building becomes part of a new arts complex which includes the Jeffrey H. Loria Center for the History of Art and the Robert B. Haas Family Arts Library.

In 2013, Yale alumni announce a project to restore the original mural by Sewell Sillman that was destroyed in the 1969 fire. They reach out to the Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation (now the Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture) for archival reference photos

“It is gratifying to know that the world of academic honors and medals has so profoundly acknowledged the Bauhaus doctrine of architectural education as taught at Harvard since 1937, because never before has a curriculum turned out such a star roster of infidels. Johnson, Lundy, Barnes, Rudolph, Franzen, and others have revered their teacher while confounding his teaching. They have left the safe anchorage of functionality, technology, and anonymous teamwork to start the long voyage home to architecture as an art. A few faithfuls still repeat the old incantations, but the guns by which they stuck have stopped firing while those of the apostates are blazing.”

“[The building is] big and gutsy enough to let you hammer at it without destroying it.”

“The spirit of its maker hovers over it so in the beginning it was hard for someone else to do something. I disapprove of the Art and Architecture building whole-heartedly because it is such a personal manifestation for non-personal use. However, I enjoy very much being in it.””

“Mr. Rudolph didn’t feel the need for privacy that I do.”

“On the exterior, the casual observer will understandably be reminded of Le Corbusier, though the scored surface of the concrete is a device unique to Rudolph, and the distinctive effect of the surfaces and openings seems to be concerned with intersecting planes rather than with dense, impenetrable sculpturesque volumes. The building has a vague, eclectic aura about it, and there is no doubt that its author both consciously and unconsciously evoked more than a few skeletons from the closet of the modern tradition. He has done so, however, in a building that also reveals that his forms and spaces have an individual personal quality uniting a sense of practicality with one of sumptuousness - features only too rarely encountered in contemporary building.”

“External forces dictated that this building turn the corner and relate to the modern building opposite as well as suggest that it belongs to Yale University. The internal forces demanded an environments suitable for ever varying activities which will be given form and coherence by the defined spaces within. As the years go by, it is hoped other interests and activities will take place within the spaces, but the space itself will remain.”

“Surely the most controversial structure of the postwar years at Yale is Paul Rudolph’s Art and Architecture Building, just up Chapel Street from both Kahn buildings. Few structures have been as talked about, as studied, as agonized over, as publicized, as hated. It is a building that seems better discussed in the terms of literary tragedy than in the conventional vocabulary of architecture. Here, in this powerful merging of the images of Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier, came together all of the ambitions, all of the hubris, of the postwar years. It is a building of enormous passion, a kind of passion that in some ways had not been seen on this campus since the days of Wight and Street Hall, The genteel elegance of Rogers, the picturesque presentations of Saarinen are of another world altogether from this building; there is a power here that is almost explosive.

As a pure abstraction, the building holds its New Haven corner well; its lines of force seem in balance, almost in detente, with the city around it. But the interior spaces, while frequently dramatic as neo-Wrightian exercises in interpenetrating space, failed almost completely in their stated functions.

After a fire in 1969, the building has never been quite the same - the university repaired the damage in such a way as to destroy the building further, removing what integrity it did have; inside it now seems like a cross between a broken-down loft and a Holiday Inn.”

“I’ve never worked on a building that affected me as much as that one does. I’d like to think that, in spite of everything, it says something about the nature of architecture.”

“The nature of concrete and its lack of weathering capability in Northeast American cities led me to corrugated forming systems, which allowed the forwardmost edges of the concrete to be broken away, thereby exposing the aggregate with its multitudinous beautiful colors. The stain of the concrete was contained within the grooves, whereas the leading edges were constantly washed by the rain. It broke down the scale of walls and caught the light in many different ways because of its heavy texture. Light was fractured in a thousand ways and the sense of depth was increased. As the light changed the walls seemingly quivered, dematerialized, took an additional solidity. ”

“Rudolph Hall’s robust exterior belies the openness of its interiors. A particular feature of the building’s

structural design is its quality of openness, which is reminiscent of the massive vertical piers and central hall of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Larkin Building (1904). Without duplicating the Larkin Building’s static axial quality,

Rudolph achieves similar spatial effects by situating the entry staircase off-center, and layering horizontal loft

spaces, to set up a ten-story building in 37-layers - each layer encompassing aspects of the central hall - held

together by vertical shafts of structure and service. Occupants circumnavigating the building experience the many subtle structural variations of its distinctive levels, passageways, and alcoves, and ascent offers a sense of

grandeur produced by shifting proportions.”

DRAWINGS - Design Drawings / Renderings

DRAWINGS - Construction Drawings

DRAWINGS - Shop Drawings

PHOTOS - Project Model

PHOTOS - During Construction

PHOTOS - Completed Project

PHOTOS - Current Conditions

LINKS FOR MORE INFORMATION

Yale School of Architecture website

The Art & Architecture Building on Emporis

RELATED DOWNLOADS

A Rare Opportunity to Extend 'Paul Rudolph And The Twentieth Century Monument' Into the Present - George Ranalli, FAIA, 2019

PROJECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Rohan, T. (2014). The architecture of Paul Rudolph. New Haven, Conn.: Yale Univ. Press.

“Consultant To Design Downtown Project.” Altoona Mirror, September 30, 1975. p.52

Pommer, R. (1972). The Art and Architecture Building at Yale, Once Again. The Burlington Magazine, 114(837), 853-861.

Spade, Rupert, ed. Paul Rudolph. London: Thames and Hudson, 1971.

Rudolph, P. and Moholy-Nagy, S. (1970). The Architecture of Paul Rudolph. New York: Praeger, pp. 120-137.

Brown, V. (1969, November 16). Wood Panels For Decorating. Sarasota Herald Tribune, p. 65

“Art And Architecture Tour.” Westport Town Crier, May 07, 1964. p. 34

Scully, Vincent. “Art & Architecture Building, Yale University”. Architectural Review, May 1964.

“Noted (With Comment).” New York Columbia Spectator, November 12, 1963. p. 4