What is wind shear? An atmospheric scientist explains how it can tear apart hurricanes

Weather forecasters talk about wind shear a lot during hurricane season, but what exactly is it?

I teach meteorology at Georgia Tech, in a part of the country that pays close attention to the Atlantic hurricane season. Here’s a quick look at one of the key forces that can determine whether a storm will become a destructive hurricane.

What is wind shear?

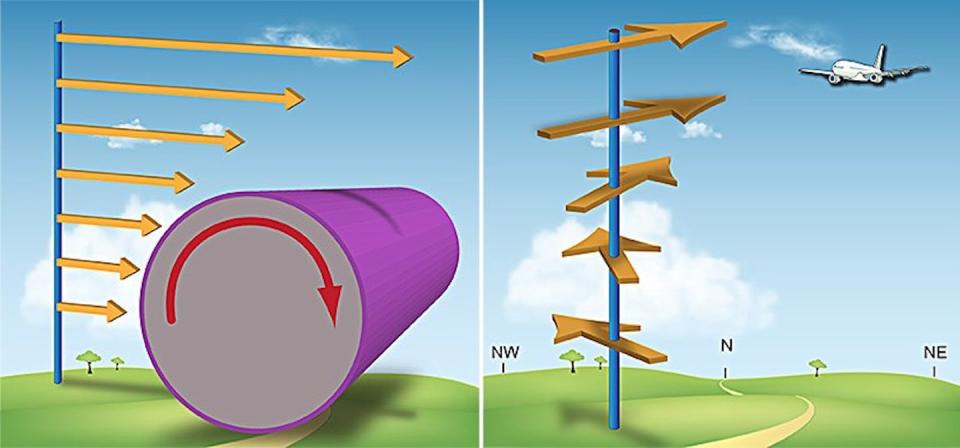

Wind shear is defined as the change in wind speed, wind direction, or both, over some distance.

You may have heard airplane pilots talk about turbulence and warn passengers that they’re in for a bumpy ride. They’re typically seeing signs of sudden changes in wind speed or wind direction directly ahead, and wind shear can sometimes cause this.

With hurricanes, the focus is usually on vertical wind shear, or how wind changes in speed and direction with height.

Vertical wind shear is present nearly everywhere on Earth, since winds typically move faster at higher altitudes than at the surface. It can be stronger or weaker than normal, and that’s especially important during hurricane season.

Tropical storms typically start as a tropical wave, or low-pressure system associated with a cluster of thunderstorms over warm water in the tropics. Warm air over the ocean surface rises rapidly, drawing in fuel for the storm. The winds begin to rotate and can intensify into a tropical storm and then a hurricane.

Hurricanes thrive in environments where their vertical structure is as symmetrical as possible. The more symmetrical the hurricane is, the faster the storm can rotate, like a skater pulling in her arms to spin.

Too much vertical wind shear, however, can offset the top of the storm. This weakens the wind circulation, as well as the transport of heat and moisture needed to fuel the storm. The result can tear a hurricane apart.

El Niño’s and La Niña’s influence

Wind shear becomes a hot topic during El Niño years, when wind shear tends to be stronger over the Atlantic during hurricane season.

An El Niño event occurs when sea surface waters in the eastern Pacific Ocean basin become significantly warmer than average, while western Pacific Ocean basin waters become cooler than average. This happens every two to seven years or so, and it affects weather around the world.

During El Niño events, upper-level winds over the Atlantic tend to be stronger than usual, and thus stronger wind shear results. The faster air flow in the upper troposphere leads to faster wind speed with increasing height, making the upper atmosphere less favorable for tropical storm development. The eastern North Pacific, in contrast, tends to have less wind shear during El Niño.

No two El Niño events are the same, of course. In 2023, record warm sea surface temperatures threatened to power up hurricanes so much that El Niño’s increase in wind shear couldn’t tear them down. For example, Hurricane Idalia fought through the wind shear in August and hit Florida as a powerful Category 3 storm.

El Niño’s opposite is La Niña – the two climate patterns shift every two to seven years or so. La Niña allows for more active hurricane seasons, as the Atlantic saw during the record-breaking 2020 season. La Niña conditions were expected to develop by fall 2024, and the Atlantic hurricane forecasts reflect that with expectations for another busy season.

The 2023 Atlantic hurricane season was a good reminder that there are always multiple factors at play affecting how destructive hurricanes become. Nevertheless, vertical wind shear will always be present and something meteorologists will keep an eye on.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Zachary Handlos, Georgia Institute of Technology

Read more:

What is hurricane storm surge, and why can it be so catastrophic?

Some coastal areas are more prone to devastating hurricanes – a meteorologist explains why

Zachary Handlos receives funding from the National Science Foundation. He is affiliated with the American Meteorological Society.