Ron Burkle, who has long been obsessed with gaining control over the hidden levers of power and celebrity, is like a boy who can’t resist playing with fire. News that the liberal, California billionaire has emerged as a likely buyer for the National Enquirer is the latest startling twist in the long history of that tabloid, which was founded as a muck-raking New York weekly in 1926.

To some, it might seem odd that a major Democratic Party donor and longtime friend of Bill Clinton would want to buy such a lowbrow, conservative outlet. After all, it is widely credited with assisting Donald Trump’s ascent to the presidency, with its “catch-and-kill” strategy of burying reports about his alleged affairs.

But to those who know Burkle, it’s just also another step in his risky, decades-long tango with the gossip press. It’s a dance that has left him bruised on more than one occasion.

Burkle's Long, Tangled Relationship with the Tabloids

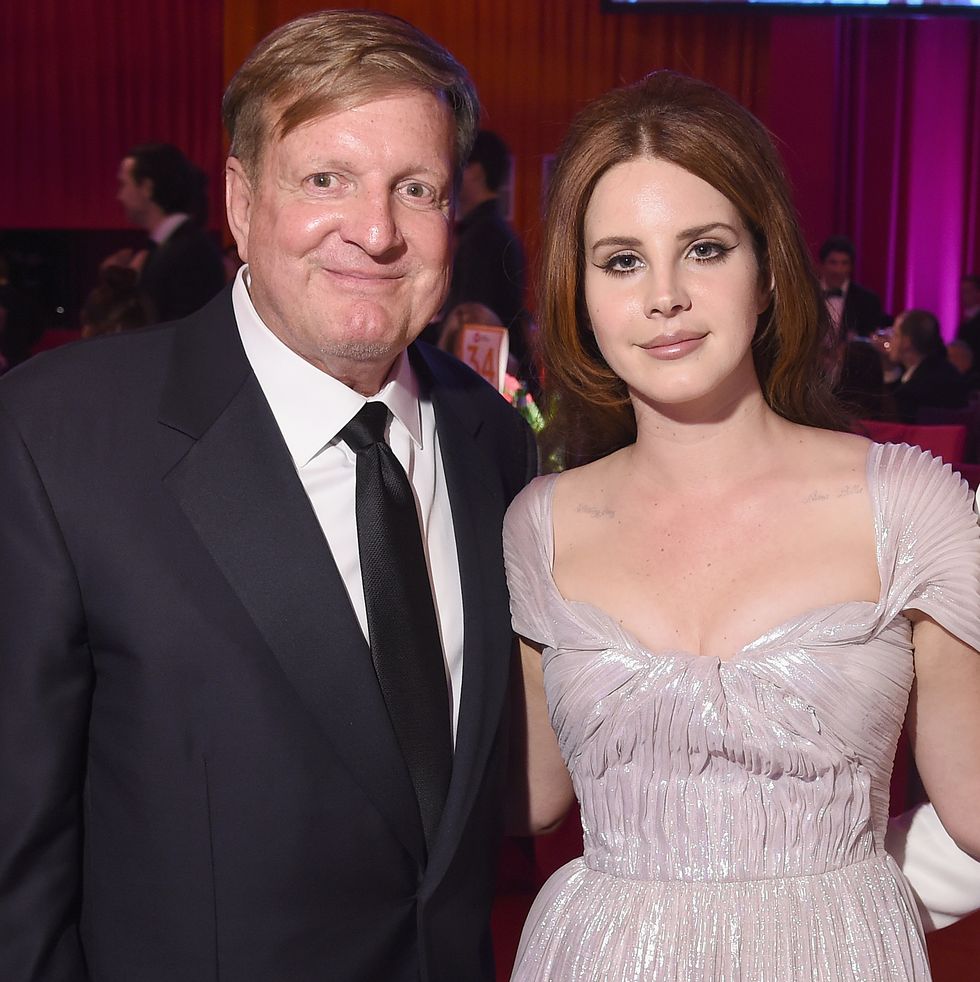

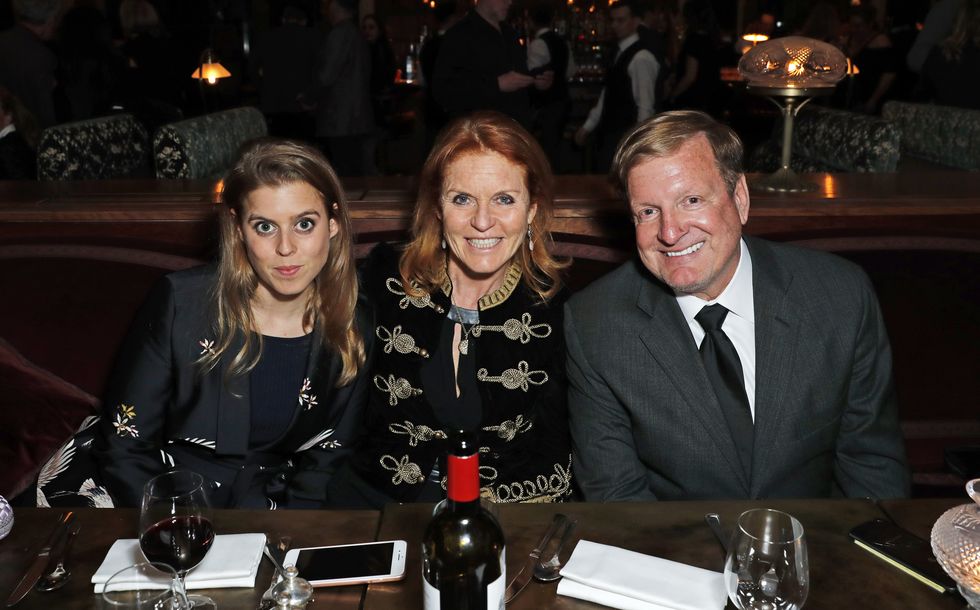

Burkle has long enjoyed appearing in the New York gossip columns. Since the mid-2000s, when he divorced his wife, his name would often be cited as a guest at model-filled social events, or alongside celebrities such as Paris Hilton.

At the time, his public image was of a supremely eligible, billionaire bachelor. His personal Boeing 757, which included a private bedroom suite, and was often used to transport important pals like the former president, was known colloquially among gossip journalists as “Air F**k One.”

Burkle would often call reporters directly—myself included, during my years at the Daily News—to spin the item of the day. (It was unusual to hear from a billionaire personally, and he shared this habit with only one other peer: Donald J. Trump.)

Often the conversation began under the pretense of “keeping his name out of the paper.” But this was just a cat-and-mouse game, and we both knew it: Burkle loved seeing his name in boldface, alongside the beautiful and glamorous starlets of the moment.

As a mogul used to running a grocery retail and investment empire, however, he was driven to try and control the narrative. In 2006, this strategy backfired spectacularly.

Burkle Attempted to Take Down the Post

Many gossip columnists at Rupert Murdoch’s New York Post were known to take money from personalities they covered through various side-hustles. Harvey Weinstein gave some reporters book deals through the publishing arm of Miramax; other studio heads offered writers “script development deals,” and one top editor simply accepted bags of cash.

For Jared Paul Stern, who at the time was second banana at the Post’s influential Page Six column, the ancillary business was fashion design. He bought black polo shirts (which were all Burkle ever seemed to wear) cheaply over the internet from China, added a pirate logo, and voila: the label “Skull & Bones” was born. These he offered to Burkle for sale in bulk—perhaps as holiday gifts for his large staff, or so went one suggestion.

Burkle hated the Post for its conservative politics and, he felt, unflattering personal coverage. He tried complaining about it directly to Murdoch, his fellow billionaire, but been rebuffed.

So he took matters into his own hand, launching a sting operation, complete with hidden cameras, hoping to catch Stern accepting cash. But the reporter was too smart to take the proffered gym bag full of greenbacks, and the ensuing scandal coverage (my own rival tabloid was only too happy run it on the front page for weeks) was as messy as it was inconclusive.

Stern got run out of town, but avoided criminal charges. Burkle botched his kill-shot, and didn’t come out looking so great himself. Many observers were left with the impression that he really was the paunchy, devious, model-chasing older rich guy that the Post had always made him out to be.

Burkle and Anthony Pellicano

But Burkle’s fascination with the hidden workings of celebrity didn’t stop there. He also couldn’t resist inserting himself into the corresponding milieu on the West Coast.

In 2002, he told the FBI he had been contacted by the disgraced Hollywood private investigator, Anthony Pellicano, who had a reputation for starting the fires he charged clients to put out, with an offer to disappear a problem for $250,000.

Burkle characterized this as a shakedown attempt. Rather than running a mile, however, he kept Pellicano in his orbit, and even became enmeshed in the investigator’s byzantine web of Hollywood schemes.

At one point, for example (according to statements made to the FBI) both Burkle and the Hollywood power-agent Michael Ovitz were paying Pellicano to investigate each other.

All of this adds up to a portrait of a very wealthy man who has a track record of engaging, not especially deftly, with the machinery that drives celebrity, power, and even national politics. Now he wants to buy the National Enquirer.

What could possibly go wrong?

Ben Widdicombe reports for T&C on the nexus of privilege and power, and the bad—and occasionally good—behavior of the very rich. He also writes the "No Regrets" column for the New York Times.