He confronted agribusiness companies, governments, and extractive scientists. It marked a before and after in the debate on the GM model, confirming that glyphosate is lethal to embryos. It was taken up by socio-environmental assemblies, peasant movements, and indigenous peoples. From the Peronist Youth to Zapatismo, from Conicet to the territories in struggle. Andrés Carrasco: heretic scientist, political activist, and, ten years after his departure, a review of his history and legacy.

Reality is too important to be left to scientists. People have profound knowledge that science does not want to learn. The struggle against extractivism is shaking the foundations of today’s supposed progress/development. These are just some of the lessons learned by Andrés Carrasco, part of the scientific establishment, who changed his life (and the lives of many) in 2009 when he confirmed the deadly effects of glyphosate. Not only that, he also confronted multinationals and governments, rejected the hypocrisy of Conicet and the Ministry of Science, and decided to walk alongside socio-environmental assemblies, indigenous peoples, and peasants.

From Conicet to the territories

Andrés Carrasco was a fighter. From the Peronist youth of the 1970s until his last days, he was “out in the open”, but surrounded by socio-environmental assemblies and fumigated villages. His political parable perhaps explains the struggle of his life: decades in the shelter of Peronism, the electoral dispute, and the occupation of state spaces (what some understand as “power”) to try to change reality from there; until his last journey, to the Zapatista School, far from those old structures that only consolidate a form of domination: where those at the top rule and those at the bottom obey and die.

It is impossible to describe the milestones of a life, but it is possible to try to describe its breaking points: Teacher, doctor, his declaration of love in an ambulance to Ana María (who would be his partner for decades and the mother of his two children, Andrés and Luciana), the militancy of the 1970s, exile in Switzerland (and then the United States), the publication on the Hox genes (which marked a milestone in embryonic development research and was published in the prestigious journal Cell), His return to Argentina with just enough, the creation of the Molecular Embryology Laboratory at the UBA, Peronism (again), the presidency of Conicet (under Frepaso and the Alianza), contradictions, support for Kirchnerism, once again a civil servant (Secretary of Science at the Ministry of Defense) and the beginning of the definitive break. Science and militancy accompanied him throughout his life.

“I did not discover anything new. I only confirmed in the laboratory what so many people were denouncing in their territories,” he explained when he published his study on the lethal effects of glyphosate on amphibian embryos.

Never before had an Argentinean scientist of his stature – he was part of the establishment – dared to question the GM model to which all sectors of power in the country (politicians, media, corporations, gringo-conservative businessmen-producers, the judiciary) drink.

And not only that. In a very risky political-ideological decision, Carrasco did not wait for the age of scientific journals. He chose a mass medium (the newspaper Página12). In this way he won another “enemy”, the bureaucrats of science, those who are locked up in their laboratories and never set foot in the countryside. Those who write those texts that only specialists understand and who prefer their academic parchments.

It was the 13th of April 2009. And nothing was ever the same.

The attack was brutal and on several fronts. Grupo Clarín and La Nación from the media. Lino Barañao from the government. Casafe (the chamber that brings together the big agrochemical and GM companies) from the corporations. Aapresid and Mesa de Enlace from the agricultural employers.

They went so far as to say that their research did not exist.

Far from backing down, Carrasco gave a lengthy interview to Página12 in which he responded to all the aggression and went further: “What is happening in Argentina is almost a massive experiment.

The rest is well known. To summarise: he increasingly questioned the academy, the governments, and the companies. He moved closer and closer to the socio-environmental assemblies, the peasant movements and the indigenous peoples. He opened himself to other knowledge (“ecology of knowledge”), visited every territory in the struggle against extractivism, argued with whomever and wherever he could, questioned his peers.

Some think he was left alone. Others believe that he chose who he would walk with.

We shared moments where he supported both theories. The first thing I heard from him was a definition that is both descriptive and a life choice: “We decided to build in the open air. You are not afraid of the wind, the rain hits harder, the sun burns the skin and, above all, the force is easier to identify and feel. You are also freer in the open air.

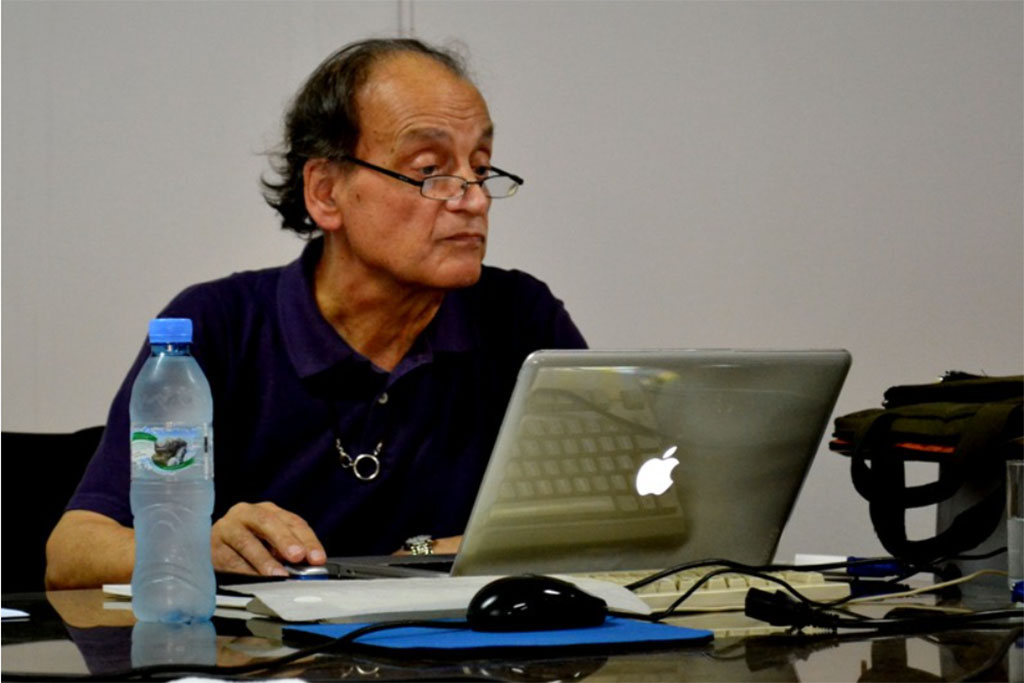

Photo Nicolas Pousthomis

Photo Nicolas Pousthomis

Censorship and cynics

The smear campaign against Carrasco had several players. The spearhead was the Minister of Science, Lino Barañao, who was linked to the GM companies and the Green Dollar. They knew each other. There was even a certain camaraderie in the past. But Barañao, in his role as a civil servant, showed his accommodating, “pragmatic” face, the defender of politics without ethics or loyalty, they say. And he attacked Carrasco wherever he could: on television, at the Aapresid Congress, in Clarín Rural, in various government offices.

On the radio station of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, Baraño went so far as to say that glyphosate was ‘like water with salt’. Barañao became so politically accommodating that he later became a minister under Mauricio Macri. The last straw came when he asked the ethics committee of Conicet (Cecte) to condemn Carrasco for his statements in Página12. This measure failed because the information was leaked to the press and Otilia Vainstok (coordinator of the Cecte and part of the maneuver) estimated that it could snowball.

The University of Buenos Aires (UBA), which usually presents itself as a beacon of plurality, has censured Carrasco at least twice. The Faculty of Medicine, where he taught and had his laboratory, prevented him from presenting his work on glyphosate. It hurt him to be banned in his own house.

And the Faculty of Exact and Natural Sciences prevented him from giving a seminar on the role of science, the extractive model and those responsible. In the same faculty, he was also confronted by the political-academic stranglehold of Alberto Kornblihtt (known as “the messiah of science”), who used his influence to lobby against Carrasco and his criticism of glyphosate. Paradoxically or not, years later Kornblihtt turned out to be a scientist committed to the campaign for legal, safe and free abortion. The interests of the GM companies and the government of the day must have been out of the equation.

In Chaco, in the town of La Leonesa (contaminated by the toxic agrochemicals of a large rice company), he was almost lynched for trying to give a talk. The final blow came in September 2013, from the Conicet, when he was denied promotion to senior researcher (the highest rank) in a rigged decision. The jury was unusual: a specialist in Buddhist philosophy (Carmen Dragonetti), a scientist linked to agribusiness companies (Néstor Carrillo) and an academic denounced for his role during the dictatorship (Demetrio Boltoskoy).

Roberto Salvarezza, who was president of Conicet, signed the rejection but distanced himself from the decision. Carrasco even met with him, but there was no way of getting justice. “Conicet is absolutely committed to legitimising all technologies proposed by companies. The best scientists are not always the most honest citizens, they stop doing science, they silence the truth to get positions in a model with serious consequences for the people,” Carrasco said.

Even though he thought he would not get the promotion, it hurt. It was the consequence of a whole career. But what hurt even more was that friends at the academy itself turned their backs on him. They left him alone, more open than ever. He took refuge in the social movements. And he continued to travel the country.

From the fumigated villages to the indigenous Zapatistas

Esquel, Famatina, Rosario, Malvinas Argentinas (Córdoba), Mar del Plata, Saladillo, Río Cuarto (where part of his ashes are) and Chaco are just some of the territories that Carrasco visited to share his research, denounce the GM model, question hegemonic science and insist on other ways of life.

Los Toldos (Province of Buenos Aires) was his last public activity (March 2014), where he was already in poor health, but he had promised to go and he did. The city council of Los Toldos was debating an ordinance to limit the use of toxic agrochemicals. And he was invited by the local assembly.

“His presentation was extraordinary. Everything he detailed from his study was what was happening here to the people, to our families; the illnesses, the deformities, everything that the poisons were causing. We were all very moved, we hugged him, we thanked him. He received a standing ovation,” recalls Margot Goycochea of the Los Toldos Environmental Forum.

She points out that he visited the town several times and never accepted payment for a litre of petrol. “He strengthened our struggles. He was a person of rare nobility and great generosity. Andrés is in the hearts of the people of the Environmental Forum and in the hearts of all of us who are fighting for a dignified life in the countryside,” she concludes emotionally.

Photo: periodicoimpacto.com.ar

Photo: periodicoimpacto.com.ar

Her last trip was to Chiapas, to the Zapatista School, an emblematic training centre for “other possible worlds”.

It is very difficult to imagine a scientist with a curriculum that draws on other popular and indigenous knowledge in order to dismantle and question existing knowledge. But Carrasco was there.

Raúl Zibechi, a Uruguayan journalist, happened to meet him in the room. He recalls that the conditions there (in the Mexican countryside) were difficult for outsiders to the indigenous world: no toilets, no showers, a plank for a bed. The vast majority were young, under 30. For those over 60, like him and Carrasco (there were also the historic Hugo Blanco and the anthropologist Rodrigo Montoya, both from Peru), there was the possibility of a more secluded room with other comforts, which Subcomandante Marcos once christened for “VIP guests”.

“But Andrés did not want to be treated differently; he chose to go to the indigenous community, to sleep on the floor, to be one of the others. It seemed to me that this revealed who he was, his character, his commitment, beyond his ideological origins, his political views; because you can be very radical in your words, but then you can stay in your comfort zone, and Andrés had the virtue, despite his age and with all his experience, to go out of his comfort zone, to live in a Zapatista community. This is very important, it shows that Andrés’ radicalism was a radicalism of life, not of posturing, it was a radicalism of real commitment, not just words,” explains Zibechi.

And he emphasises the second aspect: “Andrés was just another student at the Zapatista School. Those who taught there, those who gave classes, were the indigenous communards, people who would hardly have the fluency of speech and writing that Andrés had, let alone his ‘academic parchments’. And that seems to me to be an important, great thing. He went to learn in the indigenous Zapatista communities.

“For me, these two facts together show a human and political side of Andrés, in the sense that he was willing to learn from the common people, from those at the bottom. And even when he was already ill, he didn’t think in terms of personal benefit or comfort, on the contrary. All this puts him in a very special place,” says Zibechi.

Ethics, happiness and legacy

“I have never seen him so happy. He was at his best,” sums up his daughter Luciana, recalling the years after he had spread the word about glyphosate work. They went on a trip together, to Mar del Plata, where she saw him in action. She had never been to one of Carrasco’s scientific lectures, and there she saw a side of her father’s fullness, where the scientist felt he was contributing to a collective struggle.

“It’s like he was always looking for that. And he found it. He was able to combine all the aspects and passions of his life,” says Andrés Jr. And he adds another important ingredient: he was somewhat distant from his father, with differences they could not remember why, and the path the embryologist took after 2009 brought them closer together again. They shared conversations and wine, debates and political views. Dialogues that lasted for hours.

Jaime Farji, Andrés’s companion through decades of militancy and co-host of the radio programme ‘Silencio cómplice’ on FM La Tribu, defines him in a few words: “He was a political animal. And he did politics until the last day of his life”.

A fact that everyone stresses, even if sometimes as something not so positive, was Carrasco’s deeply ethical character. “He had very high standards. He fought with lifelong friends over political differences when he considered something unethical or contradictory, especially with Kirchnerist or leftist sectors,” he recalls.

But Andrés’ son adds two other factors, while noting that he does not have an idyllic view of his father: “He was extremely honest and always careful about the coherence of what he said and what he did”.

Ana María Quiroga, his partner of three decades and the mother of his children, was a privileged witness to their journey, with its ups and downs (until their separation in 2006), their individual achievements and as a couple. “Science, politics and what was happening to people were always on his mind.

Photo: German Villamor

Photo: German Villamor

He died on the night of 9 May 2014. In an article written with tears that would not stop, we said: “Carrasco became a heretic referent of Argentine science. There will be no farewell in the mainstream media, no words of condolence from public officials, and no tributes in academic institutions. Andrés Carrasco chose a different path: he chose to question a corporate and governmental model, and he chose to walk alongside peasants, fumigated mothers and peoples in struggle. There was no meeting where he was not mentioned. There is no newspaper, scientific journal or academic congress that would not allow him to enter where he did, by the force of his commitment to the people: Andrés Carrasco already has a place in the living history of the fighters.

Ten years later, it is confirmed every day that he is a banner for the people who reject extractivism and build other realities. And also that he is a seed and a fruit: there are schools and colleges named after him, the Union of Scientists Committed to Society and Nature (Uccsnal) was born (his idea), and there is a whole generation of young academics who take him as an inspiration and a reference. On 16 June, the day of his birth, the Day of Dignified Science is celebrated.

Carrasco showed that it is possible to put knowledge at the service of the people and, at the same time, to confront power, to feel the fullness of life, combining what one says with what one does, not allowing oneself to be domesticated by those at the top and, at the same time, being happy with those at the bottom. This is also his triumph and part of his legacy.