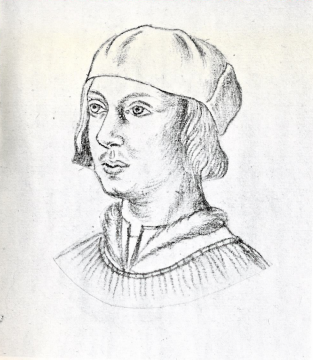

“No one, in a word, was ever more worthy to be a king’s son and the son of that king”: Desiderius Erasmus on Alexander Stewart, Archbishop of St Andrews

(A drawing of Alexander Stewart from the Receuil d’Arras, a mid-sixteenth century book containing many drawings of important figures which are thought to be copies of earlier paintings)

King James IV was not the only member of his immediate family to die at the Battle of Flodden in September of 1513. Also present was his eldest child, Alexander, then around twenty years old. His death, though less broadly catastrophic than that of the king, was still a loss which threw the Scottish church into disarray. The young man, like many others who fell at Flodden, was mourned by those who knew him, and most memorably by his old teacher, the great humanist Erasmus, who oversaw some of his education in Italy for a short period. Though Alexander was an interesting, if short-lived, figure in general, and I’ll probably go into more detail about him some other time, I’d just like to briefly cover his education and links to Erasmus in this post, because it is useful evidence of Scotland’s cultural state at the time, and Erasmus’ comments on Alexander provide a valuable insight into his character.

Alexander Stewart was probably born around 1493, the son of James IV by his first long-term mistress Marion Boyd, niece of the Earl of Angus. He had one full sister who lived to adulthood- Katherine Stewart, Countess of Morton- and also many half-siblings, both illegitimate and legitimate. On his father’s side four of Alexander and Katherine’s younger half-siblings lived to adulthood- Margaret Stewart, Lady Gordon, James Stewart Earl of Moray, Janet Stewart Lady Fleming, and the future King James V. They also had many half-siblings from their mother’s marriage to John Mure of Rowallan. Alexander’s early life is somewhat shadowy but by the early 1500s he seems to have been attached to the royal court and travelled with his father around the realm. At this time he was primarily under the supervision of Master James Watson (later Dean of Arts at the University of St Andrews) and other university graduates. He was also destined for a career in the church from an early age, and was nominated to the position of archdeacon of St Andrews in 1502. Then, in early 1504, when he was only eleven years old, Alexander was nominated by his father to succeed as Archbishop of St Andrews, following the early death of his uncle James, the previous Archbishop and Duke of Ross. James IV was in many ways a genuinely pious monarch but it was important to his policy to bring the national church in line with the interests of his dynasty, and this could be ensured by placing junior or illegitimate members of his own family in the position of Archbishop of St Andrews. It also helped that, since both his late brother and now his son Alexander were underage (and would not reach their majority until the age of 27), the king himself enjoyed the revenues of the see, and could ensure that it developed in a way beneficial to the interests of both the Crown and the realm.

But there was more than callous nepotism at work here: James IV probably did not intend in the long run that his son should be Archbishop in name only, and Alexander had long been meant for a career in the Church. Before he travelled to the continent to complete his studies, he had been educated to a high standard by the masters of St Andrews university and, in particular, by the influential royal secretary, Patrick Paniter, with whom he seems to have had a close relationship. Although he never reached the age of majority to fully assume control of his diocese, he showed a concern for the welfare of his see, and for education, being a co-founder of St Leonard’s College, St Andrews, in 1512. Though apparently deeply loyal to his father, he was not such a pawn that this prevented him from occasionally taking a firm stand against the Crown’s ambitions in the diocese. And had Alexander been simply the king’s tool with little personal worth or skill, it seems unlikely that he would have been raised to the position of Chancellor in his late teens. What is more it seems that he was expected to actually fill the obligations of the role, rather than have the venerable Bishop Elphinstone discharge them (as had been the case for Alexander’s uncle the Duke of Ross).

(King James IV, c.1503)

Possibly the most moving and fascinating description of Alexander’s character, however, comes from a few paragraphs written by his former teacher, the famous humanist Desiderius Erasmus. When he was about 14, Alexander Stewart crossed the sea in the Treasurer in late 1507, sailing to France in the company of his cousin, the Earl of Arran, who was travelling there on diplomatic business. From there, the young archbishop continued on with a small retinue to Padua where, in 1508, his younger half-brother James, Earl of Moray would join him (Moray is less frequently referred to by Erasmus, though in 1530 he wrote to Hector Boece, the principal of King’s College Aberdeen, enquiring after the earl). In Padua, Alexander and James were first taught by the humanist Raphael Regius, but the two boys soon came under the tutelage of Desiderius Erasmus, who was also touring Italy at this point. They spent a little under two fruitful years in Padua and Siena under the eye of the great scholar. Though his time in Italy was short, Alexander appear to have gotten along well with his teacher, and he occasionally appears in Erasmus’ writings, most notably in the ‘Adagia’.

Erasmus’ ‘Adagia’ is a vast work, a collection of sayings and adages which he analysed and annotated over the course of several decades. The adage ‘Spartam nactus es, hanc orna’ (’Sparta is your lot, rule her well’) is the subject of one of the largest essays in the work. In it, he gives examples of several princes who, unwisely, became engaged in foreign wars or were distracted from the domestic affairs of their realms by the prospect of external gain, such as Louis XII of France and Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy. King James IV is also mentioned, with Erasmus lamenting:

“Prosperity and reputation, both without flaw, were his, if he had confined himself permanently within his own frontiers. He was so handsome that even from afar you could see he was a king; he had great powers of mind, incredible and universal knowledge, and unconquerable spirit, a truly royal nobility of feeling, the most perfect courtesy, the most open-handed generosity; there is, in short no good quality that might grace a great prince in which he did not so far excel as to win praise even from his enemies (…) But alas when a king leaves his kingdom, this is never a blessing for the country, and rarely for the prince. In an excess of friendly feeling for the king of France, and in hopes of diverting the English king, who was mounting serious and active threats against the French, and recalling him to the defence of his island, he crossed the frontier of his own kingdom and opened hostilities against the English. In brief, he perished, bravely but disastrously, not so much for himself as for his kingdom, and perished while still in his prime.”

(Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam)

Whilst on the subject of the disastrous Battle of Flodden, Erasmus then goes on to discuss Alexander Stewart who, whilst not himself a prince, still met his end as a result of the kind of foreign military engagements Erasmus was arguing against. That Erasmus was fond of his charge is quite apparent, and his description of the young man provides a brief insight into the character of this short-lived figure. In their time together, Alexander was to learn rhetoric and Greek, but was apparently extremely eager for knowledge in many other areas.

Having received his tuition from Erasmus in the morning, afternoons would be spent studying music, practising the flute, monochord, and zither, and occasionally singing, while at dinner he improved his theological knowledge.

Though he was not so fond of law, he is supposed to have spent much of his own precious spare time reading history books, being particularly fond of that subject. He was also remarkably even-tempered and good at smoothing over trouble, with a wisdom and maturity beyond his years, though quite shy. His loyalty to his father is also commended, though somewhat regretfully, because Erasmus blamed this for his death on the battlefield, hardly the place for an archbishop. In another work, however, Erasmus also reminisced about once being fooled by Alexander’s imitation of his own handwriting, revealing a lighter side to the youth’s personality and something of his sense of humour.

Early sixteenth century Italy was not devoid of interesting sights and experiences outside of scholarly study though- at one point, in Siena, Alexander may well have seen an unusual bull-fight where the bull was fought off using large wooden machines. He also visited Rome with Erasmus during Holy Week of 1509, then Naples, but their time together was fast coming to an end. After the visit to Naples, Erasmus returned to Rome, while Alexander took a roundabout route back to Scotland, travelling through Germany and the Low Countries on his way (it is unclear whether Moray returned with him or stayed on the continent until after Flodden). Upon his departure, Alexander gave his teacher several rings, one of which was engraved with a figure believed to be that of the Roman god Terminus. Terminus was the god of boundaries, but Erasmus also seems to have taken the ring also as a symbol of the inevitability of death and a reminder of mortality, having it engraved with the phrase ‘Concedo nulli’ (I yield to no-one), and making the figure and motto the basis of his seal. Indeed, if he viewed the ring as a symbol of mortality, his acknowledgement of the inevitability of death can only have been compounded by the news of its previous owner’s fate at Flodden in 1513.

(Flodden Field)

Erasmus was residing in the south of England at this point, and would have been aware of the worsening political relations between England and Scotland which culminated in the battle of Flodden, though the event itself took place on the northern border. Speaking of the event in his annotations to the adage ‘Spartam nactus es, hanc orna’, Erasmus gave a rather moving eulogy for his ex-pupil. Though Alexander’s death was not so disastrous for the nation as his father’s, nor as devastating on its own when compared with the general tragedy of the thousands of lives lost on that day, it is still interesting to read a brief account of a young life which was cut short all too soon- especially since tthe account was written by one of the greatest scholars of the age, whose own grief is clearly expressed, albeit in order to underline his point (though the personal touch is still very evident):

“If only his [Alexander’s] devotion to his father, admirable as it was, had been equally fortunate! Resolved never to fail his father, he went with him to the war. What pray had you to do with Mars, the stupidest of all the gods of poetry, when you were already enlisted as a disciple of the Muses and, what is more, of Christ himself? With your handsome person, your youth, your gentle nature, and the fairness of mind, what could they mean to you, the trumpet-calls, the cannon and the sword? It was, no doubt, excessive filial devotion that misled you. You proved your love for your father with a courage that was too great, and unhappily fell with your father on the field of battle. Those gifts of nature, those high qualities, those splendid hopes, were all sunk in the hurricane of a single fight. Something of mine was lost there too: the pains I had devoted to teaching you, and so much of you as was made by my efforts, I claim as my share in you.”

Flodden not only wiped out a generation of the nation’s knighthood, but also caused an acute ecclesiastical crisis: Alexander Stewart was by no means the only churchman to die that day, and in fact a reasonably large number of clerics perished, including the Bishop of the Isles, and several heads of abbeys, though his death in particular destroyed all the hopes placed in him by father, teachers, and fellow clerics. The fact that James IV was willing to sponsor his natural sons’ brilliant education and continental travels speaks volumes about the importance of both learning and his illegitimate children’s futures to the king. Meanwhile Erasmus’ own testimony indicates that Alexander, despite succeeding to the see at such a young age and by such dubious means, would likely have turned out a learned and talented prelate, capable of heading up the Scottish ecclesiastical community, had only been given more time. But his death also takes on a personal aspect in his occasional appearances in the writings of Erasmus, which are invaluable as an insight into his character, and, as well as poignantly underlining Erasmus’ argument in his analysis of the adage ‘Spartam nactus es, hanc orna’, also make a fitting memorial to a well-regarded friend and pupil.

Selected References:

‘Collected Works of Erasmus’, Volume 33, trans. R.A.B. Mynors

‘Erasmus and Biography’, Margaret Mann Phillips

‘Erasmus on His Times’, Margaret Mann Phillips

‘The Epistles of Erasmus’, Volume 1, trans. Francis Morgan Nichols

‘James IV’, Norman MacDougall

Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland

And elsewhere