This article contains spoilers for both versions of Justice League.

There’s never been anything like Zack Snyder’s Justice League—and not just because it’s a four-hour, $370 million superhero movie that premiered on a streaming video service. Innumerable movies have been taken away from their directors and finished by unhappy producers, and a generous handful of those directors have been invited back years later to restore a semblance of their original vision. But there’s never been a circumstance where two different directors effectively completed finished versions of the same movie, making two films that more or less share the same plot but are wildly divergent in terms of characterization, pacing, and tone. Comparing the two—should you have the combined six hours to watch both Snyder’s version and Joss Whedon’s—offers an unparalleled opportunity to see how much difference even small changes can make, how much a few scenes or a few lines can change the shape of a story, and, in the digital age, how much of a movie can be effectively reshot without setting foot on the set. Should Wonder Woman’s theme music play when she first appears, or when she enters her first battle, and should that theme be played by the string section or an electric cello? Film schools might balk at devoting a class to Justice League, but they ought to at least consider it.

Snyder’s Justice League and Whedon’s are so distinct—according to one report, Whedon reshot as much as three-quarters of the film—that running down all their differences would be long and unenlightening. (The short answer to what’s different in Snyder’s version is: everything.) But some changes have more pronounced effects than others, so we’ve separated out the most consequential, most dramatic, and just plain weirdest differences between the two to help you know what to keep an eye out for.

In the Beginning …

There’s no better way to summarize the difference between Joss Whedon’s and Zack Snyder’s Justice Leagues than describing how they begin. Whedon’s version opens with a viral video of a smiling Superman being questioned on the street by two adorable-sounding kids, who ask him, among other things, whether he’s ever fought a hippo. Snyder’s cut opens with an extreme close-up on the kryptonite-tipped spear that pierced the Man of Steel’s heart at the end of Batman v Superman. While Whedon’s version introduces the movie’s central threat with a goofy scene in which Batman chases a gun-wielding thug across a rooftop, Snyder shows Superman’s dying cries literally echoing around the globe, ripping outward like shock waves until they make contact with the slumbering Mother Boxes. The contrast in tone could hardly be more stark, and the divergent openings also set up two very different buy-ins for the viewer. In Whedon’s version, a cornered Parademon self-destructs and his luminescent blood leaves a gooey splatter in the shape of three Mother Boxes on the wall, which tells you that the movie is going to a do a lot of “a wizard did it” hand-waving in the name of speeding the plot along. Snyder, meanwhile, tells you he’s moving in a straight line, and he’s going to take his time getting there.

Nips and Tucks

Whedon massively reworked Snyder’s version of Justice League, but he also did what any filmmaker would do when preparing a movie for traditional theatrical release, cutting scenes that didn’t appreciably advance the plot or deepen the characters—what editors call “shoe leather”—and trimming others back so they don’t retard the flow of the narrative. Snyder’s cut puts it all back, even parts he might well have slimmed down himself if he’d had to finish the film for theaters. (It’s telling that the unfinished assembly Snyder left the production with was a reported four hours long and so is the completed Snyder cut.) When the Amazon queen, Hippolyta, needs to warn Wonder Woman that an invasion is coming, she notches an ancient arrow to her bow and lets it fly, landing miles away and lighting a signal fire that gets Diana’s attention. Snyder takes two full minutes and 21 shots to get to Whedon’s starting point, with shots of the Amazons retrieving the arrow from an even more ancient-looking box and Hippolyta gazing meaningfully at it and offering a prayer to the gods.

In story terms, those two minutes add next to nothing; everything about the Amazonians is ancient and ritualized, so it stands to reason their ceremonial warning arrow would be as well. But the sequence adds weight and a sense of myth that Whedon—who is famous for subverting tropes, not supersizing them—simply isn’t interested in. The trouble is that you can only demythologize a story about unfathomably powerful beings fighting over the fate of the universe so much, and once you’ve lost that mythic feeling, what’s left starts to seem a little bit silly.

Snyder’s version also has a lot of, to use the technical term, weird shit. Whedon’s is trimmed to a fault, prizing narrative momentum above all, while Snyder’s stops for a group of villagers to sing a Icelandic folk song as Aquaman returns to the sea, a sequence that ends with one of them huffing the sweater he left behind.* Whether any movie needs that shot is an open question, but if you feel like superhero movies have gotten too safe and predictable, Snyder’s Justice League serves up endless helpings of WTF.

A Wolf in Different Clothing

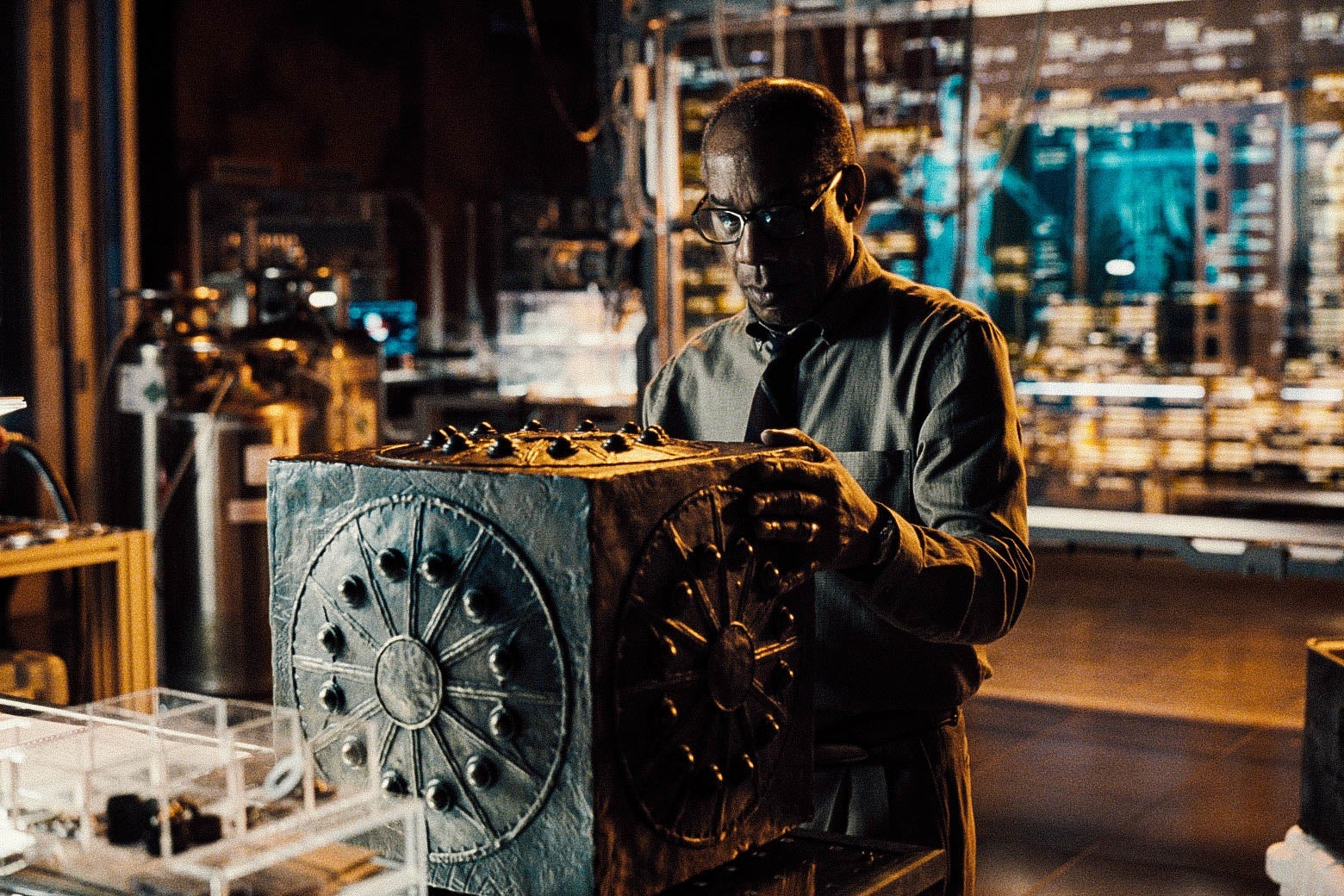

The assault on the Amazon stronghold also serves as the introduction of Steppenwolf, and comparing the two versions underlines a fascinating truth about contemporary large-scale filmmaking. So much of Justice League, in any version, exists only inside of a computer that in parts it’s effectively an animated film, which means that you can make major changes to the content of a scene without needing to reshoot a thing. Whedon’s and Snyder’s Steppenwolves look hugely different, with the latter gaining a suit of armor composed of thousands of tiny pieces of metal that can spring to attention like a blowfish’s spines. Ironically, it’s now Whedon’s version that looks unfinished, wearing what looks like a bog-standard version of medieval garb, while Snyder’s looks truly stellar. Whedon’s Steppenwolf is also quippier and creepier, referring to the boxes as “mother” like he’s cosplaying Mike Pence, and seems particularly fixated on getting under Wonder Woman’s skin. Snyder’s is fearsome but also more pathetic, an exiled soldier desperately trying to win back his commander’s approval.

Meet the Flash. Meet Cyborg.

Justice League was given the imposing—and, as it turned out, impossible—task of introducing three new characters to the DC universe: Aquaman, Cyborg, and the Flash. Whedon cut material related to all of them, but the latter two took the biggest hits. Gone from Whedon’s version is the scene that introduced the Flash, in which he breaks away from a job interview at a doggy day care to rescue a damsel in distress—and oh, his future wife—from a car crash, and a flashback recounting Cyborg’s backstory. That last bit is especially key because without it, the present-day character can seem a bit, well, robotic.

More importantly, in Snyder’s version, Cyborg and the Flash play key roles in the film’s denouement, disrupting the merging of the three Mother Boxes into the Unity that will allow Steppenwolf to effectively end life as we know it on earth. Snyder’s version establishes Cyborg as immensely powerful, with the ability to hack into any system, even an extraterrestrial one, and that makes him the only person who can get inside the Mother Boxes and prevent them from joining—but he needs the Flash’s help to do it. Not only does the Flash give Cyborg the electrical jolt he needs to stop the Unity, but he actually turns back time after Cyborg fails to stop the Unity the first time. Not even Superman (or at least this version of Superman) can do that.

In Whedon’s finale, the Flash spends most of his time running around rescuing a family of Russian civilians from Steppenwolf’s Parademons. It’s the culmination of an arc, added by Whedon to the earlier attack on the Parademon “nest,” designed to ease the Flash into the role of hero. But it also feels like a conspicuously lesser task, like the ones Whedon set for Marvel’s less powerful members during The Avengers’ Battle of New York. (Remember when Iron Man fought aliens in the sky, while Hawkeye … shot arrows at them in a bank?) Rather than feeling like full-fledged members of the Justice League, the Flash and Cyborg feel like the second string, helpful in a pinch but not equal to the heroes who’d either gotten or were about to get their own stand-alone movies.

A Tale of Two Wonder Womans

In mid-2016, Warner Bros. flew several journalists, including me, to the set of Justice League, as part of a campaign to convince the world that the movie would take a more lighthearted approach than Snyder’s Batman v Superman. (Among other things, they showed us the completed scene where the Flash tries to explain the presence of his heat-resistant supersuit by saying he’s into “competitive ice dancing.”) That campaign, however, hit a snag when the internet got hold of an offhand comment that the crimson in Wonder Woman’s breastplate came from “centuries of congealed blood from her victims.” Whedon’s Wonder Woman is more in line with the one from Patty Jenkins’ movie, a self-identified “believer” who fights with the power of her convictions.

Both versions of Justice League include a moment of sexual tension between Diana and her Justice League colleagues, but Snyder’s is a little more in the vein of a classic rom-com—Diana and Bruce Wayne brush hands while reaching for the same thing, and they both rush to apologize—while Whedon’s is, well, a little grosser: The Flash shoves Diana out of the path of some falling debris and winds up lying atop her prone body, his head pointedly nestled between her breasts. Lest the moment pass unobserved, Whedon cuts into a close-up of the Flash wobbling his eyes wildly as steam pours from his body.

Oh, and in Whedon’s version, Wonder Woman stands by, panting, as Steppenwolf is consumed by his own Parademons. In Snyder’s version, she avenges her fallen Amazonian sisters by cutting his head off with a sword.

Daddy Issues

In Whedon’s Justice League, both the Flash and Cyborg have troubled relationships with their fathers: The Flash’s dad has been wrongfully imprisoned for murder, and Cyborg’s—well, there’s the whole thing of bringing his nearly dead son back to life as a mostly machine freak to expiate the guilt of his absent parenting. But, in large part because of the expanded role those characters play in Snyder’s version, those issues become the movie’s spine. Both the Flash and Cyborg work through their personal crises at the same time as they’re saving the world: The Flash talks to his dad while he’s in the Speed Force turning back time, and Cyborg, inside the Unity, is tempted with a vision of his family made whole—his parents alive, his body restored—that he rejects in favor of accepting the world as it is. A revived Superman hears the voices of both his fathers, earthly and Kryptonian, as he’s pondering whether to join the Justice League in their fight, and Aquaman concludes the movie by saying he needs to go look up his dad (which also sets up the plot of his solo movie). As for Bruce Wayne—well, we know what the deal with his parents is, although for once we don’t actually see them snuff it.

It’s possible this is how Snyder’s Justice League would have ended all along. But given the circumstances under which he left the production, there’s a heartbreaking poignancy to the movie’s closing movement, in which Cyborg’s father, who has sacrificed his own life to help the Justice League track down Steppenwolf, speaks to his son via tape-recorded message, recounting the ways he failed as a father and telling his child how proud of him he is. It’s a film suffused with a father’s regrets, and a wish that his child know he has people to lean on. When Cyborg rejects the Unity’s temptation, he yells, “I’m not alone,” echoing the motto seen on what might be this version’s most important addition: a billboard for the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

To Be Continued

Snyder’s original vision was for a Justice League story that continued into a sequel (and possibly two), and though it’s unlikely that we’ll see a second Justice League, he restores the setup for that movie. Most notably that means the inclusion of Darkseid, the world-dominating, near-godlike entity for whom Steppenwolf is merely a henchman. Whedon’s version mentions Darkseid once, but he’s a major character in Snyder’s version, and a major factor in Steppenwolf’s desire to conquer Earth. (Although Steppenwolf is canonically Darkseid’s uncle, his aching need to convince his commander he’s worth trusting once again feels like daddy issues, galactic-style.) Snyder’s story would have had Darkseid conquer Earth himself, killing Wonder Woman and Aquaman in the process, and turning Superman evil after murdering Lois Lane. (Remember in Batman v Superman when a time-traveling Flash popped through Bruce’s computer screen to yell “LOIS IS THE KEY!!!”? This is that.) When Cyborg uses a Mother Box to revive Superman, Snyder gives him visions of the future: Wonder Woman’s body atop a funeral pyre, Aquaman skewered with his own trident, and Superman cradling Lois’ charred, fleshless skeleton. And he returns to the “Knightmare” timeline for a long epilogue in which he and the surviving Justice League members are traveling through a desiccated hellscape. (Also the Joker is there, and feeling very chatty.) Both versions end with Superman restored to his role as protector of Earth, taking to the skies once more. But Snyder continues the story to emphasize that, while Superman may temporarily be on Earth’s side, he’s a fundamentally alien being whose allegiances could shift at any moment, to be admired but also feared.

Correction, March 22, 2021: This article originally misstated that the group of villagers sang a Norwegian folk song. The song is in Icelandic.