- MIT scientists have found that wind enhances St. Elmo's Fire on the ground, but tames it in the air.

- The "corona discharge" skims harmlessly over airplanes, trees, and tall buildings.

- A controlled field could protect airplanes from much more destructive lightning strikes.

St. Elmo’s Fire may have been a career hazard, but the real St. Elmo’s Fire could help cushion airplanes from dangerous lightning strikes during flights. In new research, scientists from MIT show the special kind of electrical charge can be used to place a protective and preemptive charge around airplanes in flight, and wind affects flying versus grounded vehicles in opposite ways.

✈ You love badass planes. We love badass planes. Let's nerd out over them together.

St. Elmo’s Fire is an age-old weather phenomenon first observed thousands of years ago and eventually named for the patron saint of sailors, St. Erasmus of Formia. Its technical name is corona discharge, and, as Britannica explains with surprising poetry, it appears as “luminosity accompanying brushlike discharges of atmospheric electricity.” It’s related to lightning, and both are plasmas, which in this case means electricity accumulates and travels rapidly along a glowing cloud of ionized air.

During the right storm conditions, St. Elmo’s Fire is finally catalyzed into glowing strands of surface quasi-lightning because items like airplane wings or church steeples point into and disrupt an ionized cloud. This is when the strands appear to crawl and drift along the surface like self-adhesive lightning. The blue-purple color is due to the composition of our atmosphere, the same way different gases make different “neon” light colors.

The charge and discharge is often harmless, although more so in the sailing-ship days before anything was electrical on board. In 1980, St. Elmo’s Fire knocked out the telephone lines and weather radar in the Buffalo, New York region during a severe storm. Researchers grew especially concerned when they learned that windy conditions intensified St. Elmo’s Fire on grounded objects like buildings and trees. Anyone who’s seen a tree with lightning damage knows the “grounding” doesn’t do trees any big favors.

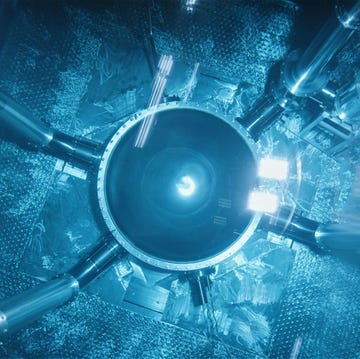

But now, scientists have found that windy conditions lessen the effect of St. Elmo’s Fire on ungrounded objects—primarily airplanes. In MIT’s now-decommissioned wind tunnel, the scientists fitted an artificial airplane wing and an artificial source of corona discharge. What explains the different results for grounded and ungrounded items?

MIT explains in a statement:

“In both cases, the wind is blowing away the positive ions generated by the corona, leaving behind a stronger field in the surrounding air. For ungrounded structures, however, because they are electrically isolated, they become more negatively charged. This results in a weakening of the positive corona discharge.”

Since airplanes produce wind as a matter of course, scientists speculate the right controlled corona discharge could be harnessed as a protective electrical field, something that’s previously been identified as a lightning-strike deterrent for airplanes.

“The results from this work demonstrate that, for electrically isolated electrodes, the corona current can actually decrease with wind and illustrate the feasibility of using corona discharge in wind to charge a floating structure such as an aircraft,” the team explains in its paper.

The now-closed MIT wind tunnel is named for the Wright brothers, who built the first wind tunnel before testing dozens of wing shapes and airplane designs. Over a century later, it’s still one of the most useful aeronautics testing grounds.

Caroline Delbert is a writer, avid reader, and contributing editor at Pop Mech. She's also an enthusiast of just about everything. Her favorite topics include nuclear energy, cosmology, math of everyday things, and the philosophy of it all.