Loud As a Crowd, Soft As a Doubt: Sparks on No. 1 in Heaven

Ron and Russell Mael discuss their magnum opus, working with Giorgio Moroder, how they felt their relevance was being threatened by the very punk bands that loved them, and their production debut, Noel’s Is There More to Life Than Dancing?

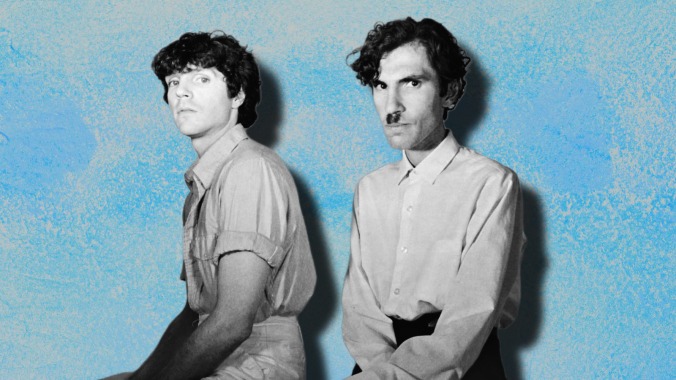

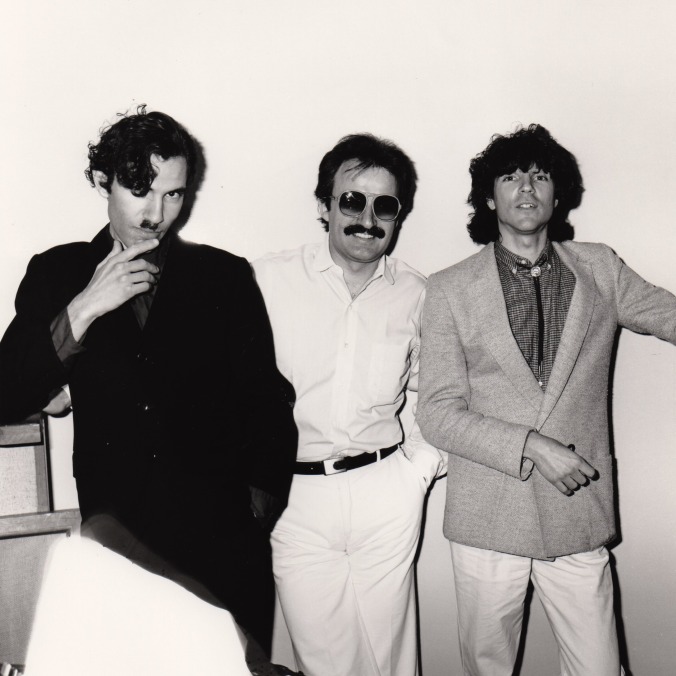

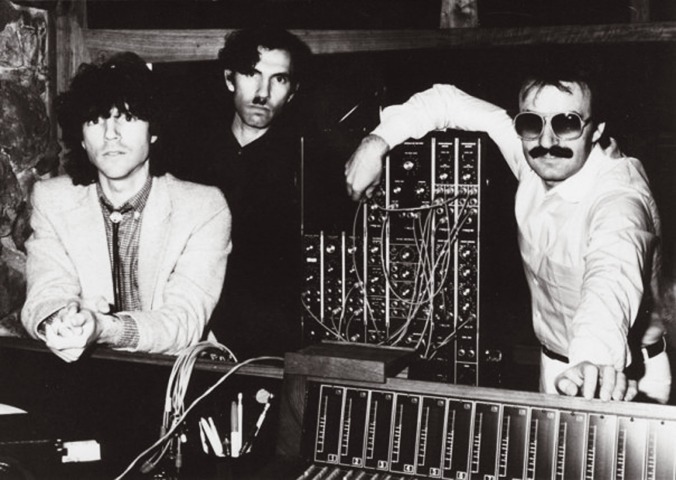

Photos courtesy of Sparks Music Features Sparks

Last summer, I ranked the 50 greatest synth-pop albums of all time. It’s a genre that has been dear to me since hearing Brian Eno’s Another Green World for the first time, and it’s one that I am still discovering corners of that were once darkened by cultural and commercial obscurity. Recently, I’ve been listening to Visage’s early catalog and Beyond the Parade, a record made by a Cleveland-born band called System 56 (a group that disbanded shortly after Cleveland Magazine, a rag I interned at when I was a lowly college sophomore, named the band in their yearly “Most Interesting People” issue). But when I held up an entire (and still ongoing) history of one genre to the light and attempted to pick the best of the best, it was clear to me, quickly, that Sparks’ 1979 magnum opus, No. 1 in Heaven, was the no-questions-asked choice for the top spot.

Because, if The Velvet Underground & Nico inspired all 10,000 people who bought a copy of it to start a band, then No. 1 in Heaven was consequential in catalyzing the impending mirage of New Wave and synth-pop that would, in most retrospects, encapsulate the 1980s altogether. The record was incredibly influential on Duran Duran and Vince Clarke-era Depeche Mode; Joy Division and New Order drummer Stephen Morris even admitted that the beat of the former’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart” was inspired by “The Number One Song in Heaven.” Never before had oddball pop music been so sharply turned on its head and, at just six songs and a 34-minute runtime, No. 1 in Heaven is brilliance on a stick—a supreme measure of the Mael brothers’ generational, multi-genre-defining vision, and their best work since ditching Todd Rundgren’s Bearsville label for Island Records in the mid-1970s.

Through Ron’s arrangements and Russell’s chameleonic, unforgettable singing, Sparks were a duo from the California Palisades who had flown under glam-rock’s radar while pushing the envelope further than just about any of their peers had. Kimono My House was an especially massive moment for them in 1974, as lead single “This Town Ain’t Big Enough for Both of Us” peaked at #2 on the UK charts and turned a lot of folks onto the group altogether. “Amateur Hour” and “Talent is an Asset,” too, were grand, progressive and orchestral fits of avant-garde pop and art rock. The Maels had left the West Coast, briefly, to record in London, where they assimilated beautifully into the burgeoning glam scene that was taking Europe by storm. When Electric Light Orchestra co-founder Roy Wood was unavailable to produce Kimono My House, Muff Winwood came in and did a bang-up job—bringing a formidable rock ‘n’ roll sensibility to balance out the Maels’ experimental urges. Sparks would fail to find that kind of seismic collaborative energy for eight years.

By the time 1978 came around, Sparks signed to Elektra in the US and Virgin in the UK—their fourth and fifth labels in seven years—because the sales behind Big Beat and Introducing Sparks had been lower than what Columbia (and CBS) wanted. Since releasing their debut album, Halfnelson (later reissued eponymously) in 1971, Sparks had made themselves known as a band—not entirely as the formative, brotherly duo they are now. All of that ensemble intrigue began to fall away around 1978. “We grow restless pretty quickly, and the advantage that we have, that Russell and I are the nucleus of the band, gives us flexibility to work in a lot of different ways,” Ron says. “We’ve felt this way at several points in our career, but we felt that we’d gone as far as we could with just a band approach and that kind of sound. We felt a little bit lost, creatively, and we were searching for a way to go, musically.”

And that way ended up being synth-pop, and the versions of it closely derived from disco and club pop. The story has always been that the Maels heard Donna Summer’s “I Feel Love,” felt deeply moved by Giorgio Moroder’s four-on-the-floor, looping production and, after telling a German journalist (who happened to be a friend of Moroder’s) about their affection towards the track, were able to get some time with the Italian producer. “It just struck us that this was something that, aside from being so striking on its own, that, as a direction, it might be a way to go,” Ron says. Sparks were especially drawn to Moroder’s ability to create a kind of music that wasn’t band- or orchestra-based. Brian Eno told David Bowie that “I Feel Love” was “the sound of the future” and it would change club music for the next decade. Moroder’s affinity for electronics and fearless ingenuity was particularly on the Maels’ radar.

“[Moroder’s electronica] wasn’t being done in a cold, robotic kind of way,” Ron continues. “It was being done in a really hot kind of way. I think we were attracted to the fact that he was able to work within that format, a completely different sound where it was based on the singer and the song. [He implemented] a real structure to it, rather than basing it just on that sound and being mechanical about it—because there had been other entries into that sort of music, but it never really involved a passion that we felt was necessary in what we were doing.”

Moroder had been the producer on Summer’s “Bad Girls,” “MacArthur Park,” “Love to Love You Baby” and “Hot Stuff,” too, establishing him as a premiere hand in the disco trend before its eventual decline in the late 1970s—around the time when Sparks would scoop Moroder up for their eighth album. By 1978, Sparks had worked with everyone from Rundgren to Windwood to Rupert Holmes to Tony Visconti to Jimmy Ienner, and their reputation for writing acerbic, cinematic, idiosyncratic lyrics, a sensibility that was leagues different from Moroder’s usual style—and it became a trademark that Ron and Russell were keen on applying to the producer’s sound and his history of minimalistic, repetitive lyricism. “His lyrics are great for what they are,” Russell says. “For Donna Summer, they’re perfect. They work perfect, where it’s something that’s just wallpaper lyrics. But ours aren’t that, so I think what added an extra element—something that Giorgio wasn’t really used to, either—was that the lyrics weren’t suitable for club consumption. Even though the music could be played in clubs, the lyrics were, really, not meant to be heard. The lyrics, they weren’t meant to be intrusive.” “It seemed like he was intrigued by that, as well—our lyrical slant,” Ron adds.

It wasn’t just the Maels’ lyrics that were outside of Moroder’s comfort zone. Russell’s singing voice wasn’t like Summer’s at all, who’d been in Munich performing in the musical Hair and working as a session vocalist by the time she started working with the producer. They both had a certain requisite of flamboyancy that was perfect for Moroder’s synth-pop, but Summer’s discipline as a soloist was perpendicular to Russell’s as a vocalist. “[Moroder] was coming from working on projects [where he is] working with one artist and he constructs the whole setting for them,” Russell says. “He put Donna Summer in that context but, with our sensibility, it was the first time he’d worked with someone that was coming from a more ‘band sensibility,’ which is really different from where I’m sure [Summer] was coming from and where Giorgio was used to coming from.”

Over the years, Russell’s vocal range has existed between the mezzo-soprano F#5 he sings in on “This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both of Us” to a baritone G2 on “Cool Places.” Some folks online have (accurately) claimed that Russell’s vocal range is “whatever Ron wants it to be,” too—which the brothers gladly echo. “With ‘This Town,’ the singing style was dictated by that melody Ron had written and even the key that he wrote it in,” Russell says. “We didn’t bother to change it to a lower key. I think that’s also the case with No. 1 in Heaven—and we think it’s a positive thing—where Ron can just write a melody and I’ll sing it, whatever it is. If it’s incredibly high then, fortunately, I can sing high. If it’s less, I’ll sing it less high. A lot of times, artists can be locked in and just singing in their comfort zone. And that’s fine, obviously. It works for millions of artists. But sometimes, you hear that on one album, where the key is exactly the same and the range is exactly the same [throughout]. It’s something we take more as a challenge, where [the key] can be all over the map, whether it’s extremely high or less. Those things are just more of a challenge, in a fun way for me.”

Something I have always loved about Sparks is that Russell’s vocals do, indeed, fit into every type of song that Ron makes for him. And Russell’s range is, perhaps, at its most heroic and beautiful on No. 1 in Heaven, as even the quasi-title track is like a kaleidoscope of pitch and tone. “The song filters down, down through the clouds,” he sings, as his soprano flirts with tenor octaves gently. “It reaches the earth and winds all around, and then it breaks up in millions of ways.” And then, as the melody drops into an ever-so-slight breakdown, Russell wraps himself around a featherlight “la, la, la” vocalization too angelic for even God’s greatest stagehands to replicate.

The lyrics on No. 1 in Heaven certainly don’t kneel to the sexy, orgasm- and liberation-minded climaxes that disco (and club pop) was used to. Instead, “Tryouts for the Human Race” comes via the POV of a sperm hoping to be fertilized. “We’re the future and the past, we’re the only way you’re gonna last,” Russell sings against a bank of epileptic synthesizers from Ron. “We’re just pawns in a funny game, tiny actors in the oldest play.” On “Beat the Clock,” the Maels wax poetic about a “born premature” youngster, who “got divorced when I was four” and “didn’t look too good in shorts,” vying for a life of sleeping with Liz Taylor and holding a doctorate after getting rejected by the army for being flat-footed. “Academy Award Performance” rings in like a feminist revision of the Hollywood that Sparks have long called home—with a particular grace extended from the band to actresses tasked with making themselves likable to the world around them while working in the company of domineering men. “There’s a goldmine in what you do, but of course you know that,” Russell sings, in one of the lower registers he explores on the record. The “you’re a girl with a thousand faces to choose from” line could easily be applied to the Maels and their chameleonic, restless directions, too.

Making the turn from glam-rock to synth-pop gave Ron more tools to arrange songs than he’d ever had before—which further vindicated their choice to abandon their band-format origins and the instrumental limitations of that circumstance. “Having worked with electronics, even though we haven’t stayed ‘pure’ in the way that it was with No. 1 in Heaven, we always have those tools available in any kind of context, even within a band context,” Ron says. “And that was something that was opened up at the time. Even now that we have a live band—and it’s the best band we’ve ever had and we love play live with this band—the acceptance to the fact that, in a live context, even in a festival context, it can just be two people and a computer, that’s something that really wasn’t there early on. You can work in any way now—either live or in a studio—and people will accept it, but early on, there was a lot of reluctance and snobbery about what constituted ‘being a band.’”

Though it is often credited as having been recorded at Moroder’s MusicLand studio in Munich, Sparks wrote and recorded most of No. 1 in Heaven at Sound Arts near downtown Los Angeles. It wasn’t until later, when the Maels would make Whomp That Sucker and Angst in My Pants, that the duo would retreat to Germany. Though it would be difficult to not absorb at least some of Berlin and Munich’s bombastic club scene had they been there, Sparks are pretty adamant that sound is fluid and not bound to any city or country. “We always felt that the locale doesn’t really, for us, change what the sound or the direction of anything is,” Ron insists. Thus, No. 1 in Heaven brandishes a unique palette: sounds fit for European dancehalls, razor-edged, cultural lyrics fit for someplace between Hollywood and the folkloric streets of Greenwich Village and a musical persona that was so unique that it rivaled the frontmanless sameness of Kraftwerk and Devo.

Ron—whose intricate keyboard stylings, scowling, emotionless deadpan and peculiar facial hair made him a stoic-yet-mythical Charlie Chaplin of the art-pop world—and Russell—whose animated, larger-than-life lead singer theatrics gave a real “black and white” contrast to the crabby sophistication exuded by his brother—exist in a vacuum. The Ramones loved them and so did the Sex Pistols—even though the Maels felt threatened by both of those bands, in terms of their own irrelevancy in the wake of punk music’s burgeoning popularity. But punk and disco were, at the end of the day but from different sides of the spectrum, trying to rebel against the musical establishment. And that’s what is so interesting about Sparks—how they have always been a band that, to me, exists a notch above punk rock, if only for their allergy to formulaic conformity. There were no linear expectations for them as a band and, yet, Sparks and a few of their punk neighbors ended up in the same place in the 1980s: as New Wave artists.

“It was a shock to us to hear [Sex Pistols guitarist] Steve Jones being a fan of the band, when we felt incredibly threatened by [punk music] and the power of it—not always just musically, but as a movement and a statement against a certain kind of thinking in bands,” Ron says. “We really loved that music but, even though there were elements of that in what we were [doing]—and we were playing songs faster than most bands when we first started—we weren’t punk in the sense of what our sound was. Being anti-establishment, in hindsight, that was really something that was always there in what we’re doing. When we did turn to electronics and worked with Giorgio for the first time in ‘78, it was also a statement. And we got criticism at the time! We get it kind of constantly anyway—we’re used to that—but it was a criticism of turning our back on the band format. And we were excited about it! None of the three of us, including Giorgio, knew exactly where [No. 1 in Heaven] was going to head. It was so hard to imagine what this was all going to turn out to be, and that was the exciting thing about going into the studio every day—just finding out and surprising ourselves, really. Giorgio, he’s a calm person but I think, deep down, he was really excited about that—as well as the unknown of it.”

A song like “La Dolce Vita” sounds like Sparks made it in an effort to intentionally satirize the Euro-pop “sweet life” that Moroder had so deftly made his hallmark—this time in the vein of a gigolo wrapping himself in the arms of rich, aristocratic women. “Looking real bored is what you pay me for, La Dolce Vita,” Russell sings after one of Ron’s keyboard solos. “Looking real bored’s as hard as scrubbing floors, La Dolce Vita.” The way the Maels muse on such a lifestyle, it comes across like they only saw it happen once and wanted to try their hand at wearing those same clothes—and it’s that type of mockery that makes a record like No. 1 in Heaven so colorful. Too, it’s that type of mockery that makes forays into disco by bands like KISS and the Rolling Stones feel all the more vampiric in 2024, especially given how quickly they retreated to their rock ‘n’ roll safehouses after disco was demolished. Sparks not only made fun of that trend-hopping with such ease—by putting literary, absurdist lyrics to the beat of Moroder’s coterie of synthesizers—but they lovingly used disco as a jumping point for their turns to disco-rock, New Wave, power-pop and synth-pop.

And even then, Sparks never really cared much about dance music in the first place. In his Sunday Review of No. 1 in Heaven for Pitchfork, Stuart Berman claimed that Sparks were making an album about disco. But the materialism and vanity and nightlife wasn’t even on the Maels’ radar, let alone being something that beckoned them to interrogate it and step into disco’s wardrobe for 30 minutes. “We had no connection with that element of that kind of music. I mean, for us, it was purely the sound,” Ron says. “We had no feelings about club life or disco balls. Perhaps it’s a letdown to people to reveal that, but it is the truth: We really loved that sound, but it didn’t matter to us that it was, maybe, something that was geared towards clubs. Wherever it could be played was fine with us.”

When folks started labeling No. 1 in Heaven as a “disco album,” Sparks often remained silent, refusing to refute such claims. How do they feel now, in 2024? “We never felt that it was [disco],” Ron says. “We thought of it as being an electronic album. Obviously, Giorgio’s been connected with disco music but, for us, [the album] was always a means to remain true to what we were as Sparks, but working within a different musical format.” “And thematically, too, I think the lyrics are what took it away from being that specific of an album,” Russell echoes. “The lyrics were so completely antithetical to the whole dance world. ‘Tryouts for the Human Race’ and ‘Academy Award Performance’ and ‘Beat the Clock,’ just to name three out of the six [songs], they’re not part of that whole world. I think that’s what makes the album more interesting, that it’s combining, sonically, elements from that disco, dance world but then it veers so far off course, lyrically, that it’s not comparable to what you should be hearing in a club.”

“Even on [Noel’s Is There More to Life Than Dancing?], there are references to dance in the lyrics, but it’s done from the slant of taking a cockeyed view of the whole thing,” Ron adds. “It’s not exactly celebrating that movement; it’s referencing it in an oblique and unique way.” Pretty quickly after finishing the No. 1 in Heaven recording sessions with Moroder, Sparks were so enthralled with that way of music-making that they wanted to take what they’d learned from their Italian producer, write songs and have someone else sing them. “We were really excited about trying to produce somebody at that time,” Russell says. So, when someone tipped the Maels off to a model-turned-singer in Los Angeles, they went to see her play a show at the Troubadour.

Ron and Russell loved not only Noel’s vocals, but her entire image (she was, after all, a beautiful, blond-haired woman who wore bright, colorful jumpsuits and personified a look that would, eventually exist parallel to the aerobics and club scenes across America in the 1980s), so, after the gig, they brazenly asked her if she wanted to “take part in a Sparks experiment.” “She took the challenge,” Russell continues. “Ron wrote a lot of songs and, then, we went into a studio—sans Giorgio, but with a lot of techniques that we had learned from him—and did an album with a female singer. But, lyrically, [Is There More to Life Than Dancing?] has a lot of our personality all over it.”

That present personality has also led to some online myths about Noel and her record. Some have speculated that she is the woman pictured on the front cover of No. 1 in Heaven. I ask the Maels if there’s any juice to that theory. “No, and she’s not the Black woman [on the back cover], either,” Russell responds, laughing. “Paul is dead!” Ron chimes in. Elsewhere, fans have noted that Noel’s singing cadence is similar to Russell’s and that, if you slow down the playback speed of the album, her vocals do sound close to his. “That’s someone with way too much time on their hands,” Russell continues. “Just accept it for what it is: She’s a real, living person who sings really well. It’s not me.”

Theories like those achieve the opposite of what Sparks—and Virgin Records—wanted for Noel; they make her relevancy contingent on the lore and fame of the Maels, which is especially a disservice, considering how good of a record Is There More to Life Than Dancing? is (and how great of a productional debut for Sparks it was). “We love all those myths, but it was really unfair to Noel when people brought that up—because we thought she was a really great singer. To make it out like she doesn’t exist, it seemed a little bit harsh,” Ron adds. In truth, Noel did quite a bit of promotion in the UK for her record with Sparks. According to Russell, Virgin had put a lot of stock in her and wanted to see the album succeed. The Monkees’ Micky Dolenz even directed a music video for “Dancing is Dangerous,” though the footage has been lost—and with Dolenz no longer having contact with his archives, re-discovering that tape is growing more unlikely by the day.

And Is There More to Life Than Dancing?, too, is the most dance-forward project Sparks have ever made, even when it’s talking about dance in a cautionary way. By the time Noel’s debut record came out, disco was on its way out—but the Maels have never been ones to really abide by the lifespans of success. And, after all, they did take a stance on that frame of thinking pretty early on, singing that “trends make us contenders in the fall” on the track “Wonder Girl” on their now-eponymous debut record. Noel’s real identity has never been made public, and she’s maintained a rather anonymous life since the mid-1980s. She led a band called Noel & the Red Wedge and put out an album called Peer Pressure with them in 1982, but has since played in more jazz-oriented groups. Sparks had lost contact with her for years, but reconnected with her during the lead-up to the recent Record Store Day reissues of both No. 1 in Heaven and Is There More to Life Than Dancing? “It’s great to know she’s still pursuing music,” Russell says.

On the re-release of Noel’s album, too, Sparks have resurrected demo versions of the songs—which include, in some cases, Ron performing some of the singing parts. “I didn’t know that,” Ron says. “Here comes the lawsuit,” Russell replies. “Sparks v. Sparks.” The Waters Singers—siblings Oren, Julia and Maxine, whose first crack at real stardom came through singing on Michael Jackson’s Thriller—are also now credited as having performed on the record, which was not the case 45 years ago. “They really shine on Is There More to Life Than Dancing? in a way that was so complimentary to both the songs and also to Noel’s voice,” Russell continues.

Sparks would produce Bijou’s Pas Dormir later in 1979, and it would become the last full-album production credit they’d have (aside from their own albums, of course). Their post-No. 1 in Heaven momentum would sustain through Terminal Jive and Whomp That Sucker, vaulting them into Angst in My Pants—their 1982 masterpiece that boasts the title-track and “Eaten By the Monster of Love,” two of the very best synth-pop songs of the decade (and ever)—before they’d ditch MusicLand Studios and Moroder’s electronic community altogether for their first-ever fully self-produced album In Outer Space (which would remain their highest-charting album in the US until 2020’s A Steady Drip, Drip, Drip.

But, 45 years ago, No. 1 in Heaven got Sparks back on the UK charts. Putting the record out, quite literally, is why we get to enjoy the blessing of the Maels still making music—like 2023’s brilliant The Girl is Crying in Her Latte—today. It’s why hearing Russell sing “This Town Ain’t Big Enough For Both of Us” during an NPR Tiny Desk performance is even possible. “It was buying us extra career time,” Ron says. “The odd thing was that it wasn’t that the album was immediately grabbed up by record companies, even with Giorgio producing it. It took some time until it found the right people. We’re really fortunate in that way. You try not to base the success of an album on how it’s done commercially, but, obviously, [No. 1 in Heaven] was a lifesaver—as far as prolonging what we could do, and especially at that point in our career, where you were more reliant on record companies and radio. Now, both of them are pretty irrelevant.”

Considering that Sparks have become one of the most beloved experimental bands of all time—and as crucial to the DNA of the modern pop canon as the musicians who first influenced them, like the Beatles, Philip Glass and Frank Zappa—a song like “My Other Voice” and its vocoder melody being so definitive and consequential to their endurance nearly a half-century on feels fabled—and, knowing that Paul McCartney dressed up like Ron in the “Coming Up” music video or that bands like They Might Be Giants and the Magnetic Fields might not exist without them (or, at the very least, not exist in the shapes we know them to now), it’s hard to imagine a world where No. 1 in Heaven didn’t soar immediately and become a hit in our cars, an advertisement in our homes, and the sounds of our children singing in the streets. It’s the sound of the future, even as we’re still living through it.

Matt Mitchell reports as Paste’s music editor from their home in Columbus, Ohio.