Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar’s important new book, Headstrap: Legends and Lore from the Climbing Sherpas of Darjeeling, tells stories from the often-overlooked Sherpa and Bhutia communities whose members have played a crucial role in high-altitude Himalayan climbing since the 19th century.

In addition to an introduction by the authors, the following excerpt contains three short profiles. The first of these tells the story of one Wangdi Norbu, who participated in expeditions to Kangchenjunga (1930), Kamet (1931), Everest (1933, 1936, and 1938) and Nanga Parbat (1934), only to lose his career (but not his life) in 1947 to a tragic, multi-stage mountain accident.

The second tells the story of Lewa, a “highly sought-after porter and sardar” who earned a coveted tiger badge as a reward for his “amazing tenacity and endurance both as mountaineer and as leader” in the 1930s, only to be tossed aside when a Western booking agent arbitrarily decided he was too old.

The last story is about Phuchung, a 21st century climber who worked for three years as a salesman in Dubai before returning to Darjeeling, attending the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute, and heading into the mountains for work. His comments about modern mountaineering would sound familiar to Wangdi Norbu and Lewa:“People don’t climb alone,” he says. “They take Sherpas who usually look after their clients very well. … Unfortunately, after they come down, only the members’ names will be on the list of those who summited. Not the names of the Sherpas—that still happens.”

—the Editors

*

The following text is excerpted from Headstrap: Legends and Lore from the Climbing Sherpas of Darjeeling by Nandini Purandare and Deepa Balsavar (April 2024). Published by Mountaineers Books. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission.

Section divider

The seeds of this project were planted in early 2012 in a remote area of Arunachal Pradesh in the eastern Himalaya. We were hiking with our old friend and trekking companion Harish Kapadia, modern India’s preeminent explorer. Travels with Harish are always filled with songs, stories, and anecdotes about the people he has met while traveling. He told us a fascinating story about the legendary climber Pasang Dawa Lama of Darjeeling—jumping naked into the icy waters of a Nepali river to advertise his having slept with one hundred women—that ignited our imagination about the community of Sherpa climbers in that hill town. We wanted to know more, and that’s how it all began.

At the end of our first visit to Darjeeling, in April 2012, we made a promise that this book seeks to fulfill: to record and share Sherpa stories and histories from this region. We uncovered many tales over the coming years, in the narrow, often grotty lanes of Toong Soong, a Sherpa settlement in Darjeeling. We found them in the warm homes of the sons and daughters of Sherpa heroes from decades ago. We traced connections and attempted to chart family trees. We discovered that there are new Sherpa climbers in Darjeeling today, but they are separated geographically, historically, and technologically from those who came almost a century ago. We dug into forgotten papers and books published by The Himalayan Club, set up in India in 1928 to encourage climbing and exploration in the Himalaya, and met with climbers all over the world who shared their memories with us.

Many of the Sherpas and other people we wanted to meet had died without anyone hearing about their remarkable lives. Over the years we returned to Darjeeling for months at a time to learn about these men and women. We kept at it, gaining confidence, making friends, and listening. The experience was both humbling and uplifting.

During the hours we spent in different homes, we realized and learned many things. We realized that memory is fallible. More importantly, our memories are not linear; they emerge from emotion, not logic, and not necessarily from fact. We occasionally came across discrepancies, either between how two people recalled the same event or between an oral recounting and a written one. For example, we interviewed Kusang Sherpa in 2013 about his arrival in Darjeeling and entry into climbing, but in his autobiography published a few years later, he recounts different details. In such cases, we have done our best to determine and recount those versions most likely to be accurate.

It took time to understand that it was the memories, personal and intimate, rather than the written accounts, that should be the focus of our work—after all, memories let us into people’s hearts and minds. Still, stories from memory are often left with gaps, which we worried about how to fill. It took time to understand that we could string together a narrative despite these imperfections, even as some facts have likely been lost along the way. We had to learn not to ask our interviewees questions that reflected our modern intellectual concerns and may be insensitive to our subjects’ conditions and priorities at the time, like “Did you ever think of doing something else to earn your living?” or “What did the women feel when their men left for the mountains?” Most of all, we learned that many Sherpas who appear in expedition accounts, both written and oral, were legendary climbers, but had no family or heirs to their stories left in Darjeeling. We are sincerely sorry that we could not cover them.

We recorded hundreds of hours of conversations, which had to be painstakingly transcribed. Narrators spoke in Nepali, Hindi, and English. The interviews were filled with hesitation, self-contradiction, doubt, and gossip. A single hour of recording took many hours to simultaneously translate and transcribe. It took a few years to record and subsequently transcribe all those conversations and interviews.

Interspersed with our trips to Darjeeling were our home lives in Mumbai, our day jobs, and our family obligations. We also took trips to other cities and towns to meet other people who knew these Sherpas and to visit libraries for research. In the early years, we were also constantly writing grant proposals and meeting with potential donors to the project. A travel agency, Cox & Kings, bought our airplane tickets for a few years, but we worked on a shoestring budget for everything else.

The hardest part came later when we had to sift through accounts, facts, dates, and names, and verify and organize them. Over 150 interviews, representing hundreds of hours, had to be condensed into a cohesive, readable, interesting narrative. Much had to be left out, in order to let the diamonds emerge.

Over the years, place names have changed. For instance, Bombay became Mumbai in 1995, and Calcutta became Kolkata in 2001. For consistency, we have gone with the more modern, Indian names for each place regardless of the timeline of the events being described, unless the reference appears in a direct quote.

A decade is a long time to write a book. Many of our narrators have died over this period. Still, we hope to keep their memories alive on the pages of this book—not an anthropological work or an academic tome but a tale about a fascinating community of mountain people and climbers. Finally, we take full responsibility for any oversights, factual inaccuracies, or misinterpretations.

Section dividerWangdi Norbu

The renowned porter Wangdi Norbu’s illustrious career encompassed many of the early-twentieth-century expeditions to the great Himalayan peaks: Kangchenjunga in 1930; Kamet in 1931; Fluted Peak in 1932; Everest in 1933, 1936, and 1938; Nanga Parbat in 1934; and several expeditions to the Garhwal and Assam. His porter book is filled with glowing testimonials from some of the biggest names of the time, like these two from the British climbers Frank Smythe and Hugh Ruttledge:

“Wangdi Nurbu accompanied the 1931 Kamet expedition. On this he did excellent work and carried to the highest camp at 23200 ft. He is a tremendous worker and thoroughly trustworthy in every way. He sets a splendid example by his tenacity of purpose under the most adverse circumstances.” —F. S. Smythe

“A real ‘stilt.’ Nearly died of pneumonia at the Base Camp, but turned up for work the moment he could. A hard case who will work splendidly for those who understand him, but he wants holding. Very strong.” —Hugh Ruttledge, Leader, Everest 1933

In 1947, Norbu’s career was cut short at the peak of his prowess by a horrific accident on Kedarnath (6,940 meters) in India. It was the first post-war Swiss expedition to explore the southwest part of the Garhwal Himalaya, and Wangdi was the Sherpa sardar. He fell while approaching the summit and slipped down an icy slope, carrying his ropemate, Alfred Sutter, with him. Their fall was arrested when the slope eased off but Wangdi suffered a broken leg, a fractured skull, and a knee severely damaged by the point of a crampon. The other climbers were unable to bring him down that day, so they injected him with morphine and left him bivouacked on an ice bridge just inside a crevasse.

A rescue team sent up the next day was unable to locate him. When the Swiss climber René Dittert along with the Sherpas Tenzing Norgay and Ang Norbu finally reached Wangdi a day later, they discovered a horrible sight. Thinking himself abandoned, in terrible pain, thirsty, and hungry, Wangdi had cut his own throat. There was blood everywhere, but he was alive. In an epic effort, the team first dragged then slid Wangdi down, and finally the Sherpas carried him to basecamp. Wangdi recovered from this accident but was never able to climb again.

Wangdi Norbu’s son Dawa Tsering recalled that a year or two later Andre Roch and other members of the expedition came to Darjeeling. They brought with them an expedition documentary made using footage filmed during the climb. Dawa remembered seeing the film at The Everest Hotel though its name escaped him. He did remember, however, that Roch gave his father a table clock and him some chocolates. Upon returning from other expeditions, Dawa Tsering told us, his father sometimes brought home good boots or a sleeping bag or leftover fruit. Other than food, everything else was soon sold because the family needed the money.

Dawa proudly showed us the relics left from his father’s career: a Tiger Badge, a porter book, a few letters, and a single photograph. When his father died, in 1952, Dawa was eleven. “After my father died, my mother burned everything. Even my father’s pictures,” he said, noting that this is a Tibetan custom. When we met him at Dorjee Lhatoo’s house, he had just entrusted his precious legacy to Lhatoo. He told us, “I gave all this material to Lhatoo because I want it to be displayed in the HMI mountaineering museum. It is very valuable.”

The porter book is the key. It helps build the story of who Sherpas such as Wangdi Norbu were. It reveals how they were perceived by the men they carried loads for, and provides a résumé of sorts of their careers.

Section dividerLewa: The Tiger Who Rejected His Stripes

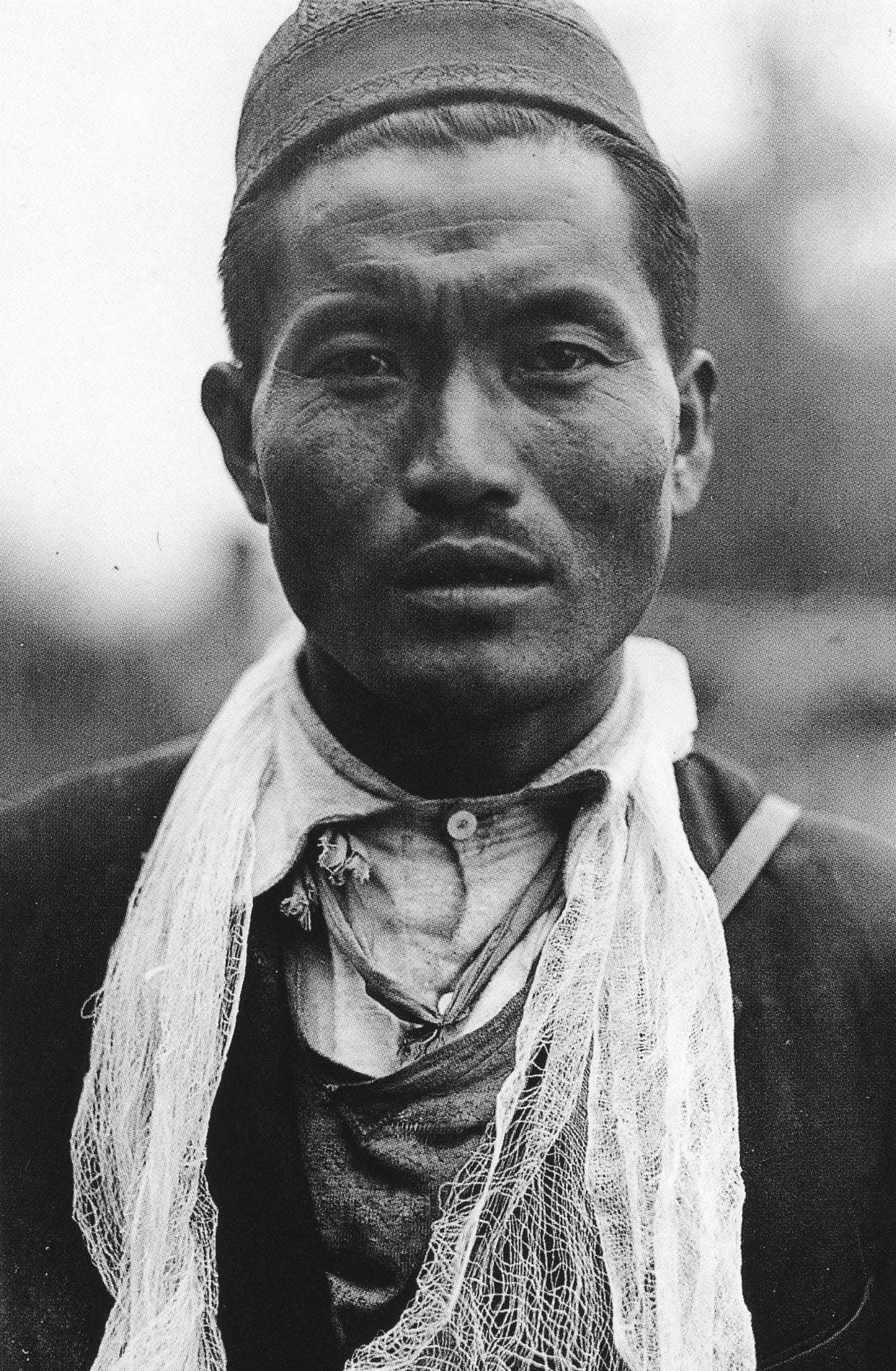

A much respected and highly sought-after porter and sardar of the late 1920s and 1930s, Lewa was with Paul Bauer on Kangchenjunga in 1929 and with G. O. Dyhrenfurth on the same mountain in 1930. He made the first ascent of Jonsong with a fellow Sherpa called Tsinabo, and despite having frozen feet, he was also on the first ascent of Kamet in 1931 with Shipton, Smythe, and R. L. Holdsworth. So severe was Lewa’s frostbite that most of his toes had to be amputated. The indomitable Sherpa was back climbing the very next year on Chomiomo. That was followed by Everest in 1933 and Nanga Parbat in 1934. Fritz Bechtold, one of the climbers on the latter peak, wrote, “As first Sirdar, Lewa was chosen, a man who hitherto had distinguished himself on every expedition by his amazing tenacity and endurance both as mountaineer and as leader.”

The final entry on his climbing record shows a series of travels through Tibet and elsewhere with the explorer and botanist Ronald Kaulback from 1935 to 1938. In recognition of his phenomenal career, Lewa was awarded the thirteenth badge when the Tiger was instituted in 1939.

In those early days, Lewa was a familiar sight around Darjeeling. Dorjee Lhatoo remembered seeing him and his friends as a child. Walking to Chowrasta from Toong Soong, the men would be holding on to each other for support after one bowl too many of tomba (a millet-based alcoholic drink fermented by tribes in Nepal, Sikkim, and Darjeeling). Lhatoo told us this story about Lewa’s badge:

“You see, Lewa went to Mr. Kydd, who was the local recruiting agent. He was well known as someone who employed Sherpas to go on expeditions and treks. Mr. Kydd said to him, ‘Lewa, you are too old. Give a chance to the younger people.’ Lewa asked, ‘So, how do we make a living?’ ‘That’s not my problem,’ said Mr. Kydd. Apart from Lewa, there were a couple of other people who were also not being employed. They had brought their badges, and they said, ‘Then why have you given us this?’ They were ignored by Kydd. Then Lewa is reported to have thrown his badge down the hill! Once he did that, the others did it too—they all threw their badges, and then clapped their hands and went home.”

Without expedition work, Lewa found a job as a watchman looking after a series of shops in Siliguri, which was just developing. He lived alone, sending what money he could home to his wife and school-going children in Darjeeling. One day in 1948, he didn’t show up for work and people assumed he had gone home. No one looked for him. Later on, when there was a stink coming from his room, they discovered the dead Lewa. Ang Tsering told Dorjee Lhatoo that they went down and brought Lewa’s body to Darjeeling to cremate, smelling to high heaven. Lewa was only forty-six years old.

Section dividerPhuchung: A Young and Articulate Sherpa

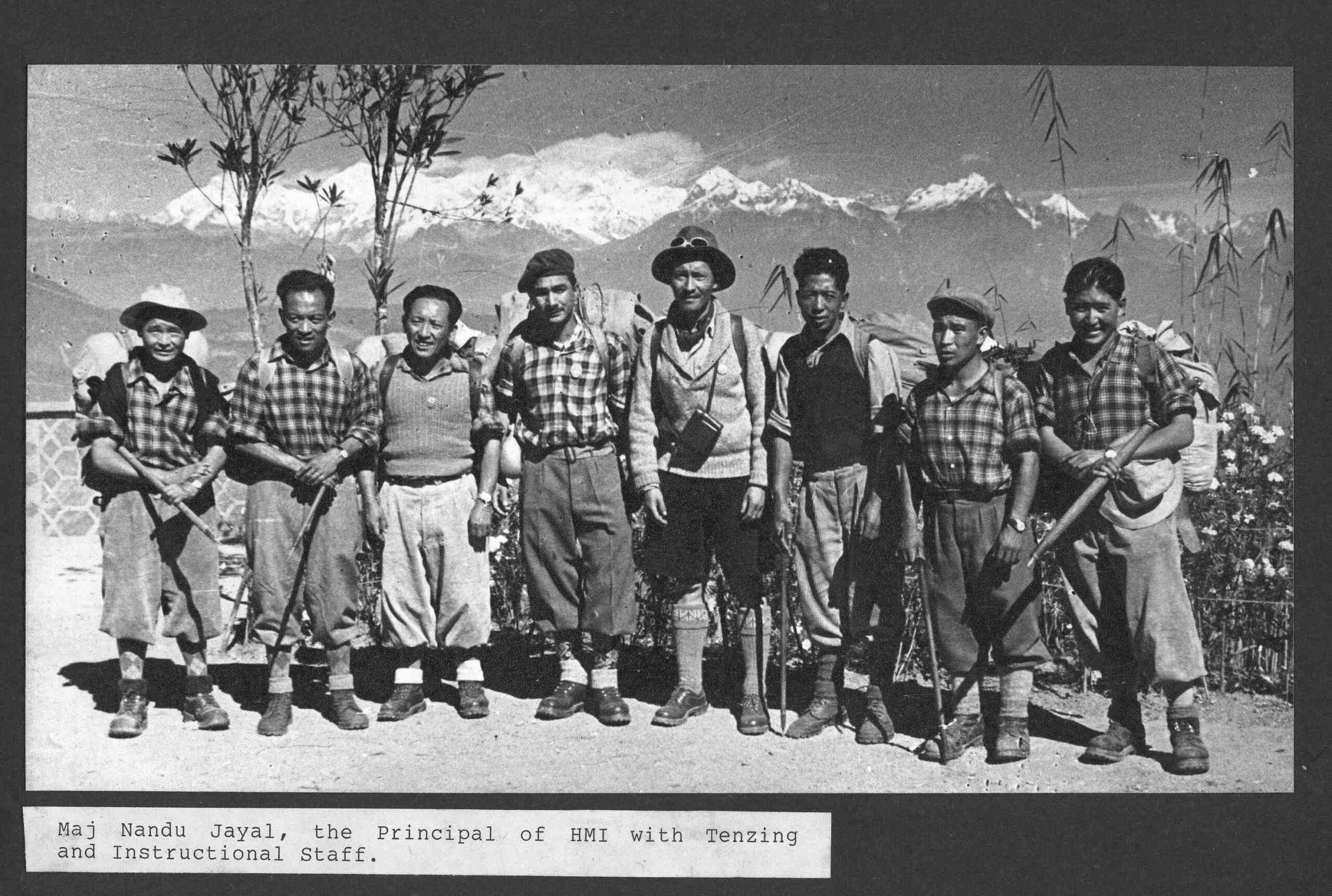

Phuchung is not from Makalu, but he is an example of the newer Sherpas. He was born in Manebhanjan, a village close to Darjeeling, and his grandparents were traders on the India-Nepal route. When Phuchung was in his first year of college, his father died and the responsibility of looking after his family fell on his shoulders. He left for Dubai, where he worked as a salesman for three years before returning to Darjeeling. Back home, he completed all the HMI courses and started working with expeditions. His brother-in-law Sangye Sherpa helped him get a job at the HMI, where he rose through the ranks from guest instructor to permanent instructor. At first, he had intended to finish college and get a government job, but Phuchung had grown to love what he was doing and he wanted to learn more. “I want to climb all fourteen peaks above 8,000 . . . Not [possible to climb] K2 on an Indian passport, but at least the other thirteen. And I am thinking of doing some new courses like ski courses and rescue courses,” he told us enthusiastically.

Phuchung climbed Everest in 2012. He told us that many older Sherpas lament the fact that Everest has become an easy climb: “People say it’s like a road, but no matter that there is a fixed rope, you have to climb by yourself; nobody is going to push you or carry you.” His ascent was tough at times, but he reminded himself, “You are a Sherpa—you can do it.” It’s this confidence that helps Sherpas lead others up the mountains. Phuchung explained, “People don’t climb alone. They take Sherpas who usually look after their clients very well. That is their duty: to climb mountains, look after their clients, and bring them back safe. Unfortunately, after they come down, only the members’ names will be on the list of those who summitted. Not the names of the Sherpas—that still happens.” What Phuchung said is important. Every year we encounter several expedition accounts in which Sherpa summiteers are not listed. In fact, there are often claims of “solo” ascents in which Sherpa support is conveniently left out.

Phuchung had recently married a Darjeeling girl. He told us, “My wife knows nothing about the mountains. I tried to explain to her that even during a course we have to look at the safety of the students, sometimes risking our lives. There is no phone network; we have to stay for twenty to twenty-five days in the mountains. But she doesn’t understand. I am thinking of making her do one course so that she can understand.”

About the authors

Nandini Purandare is editor of the internationally renowned Himalayan Journal. As a writer and editor for the Avehi-Abacus Project, she has developed educational materials for public schools across India. With a background in economics, Purandare has consulted for various organizations and research centers and is an enthusiastic trekker and avid reader of mountain literature. She, along with co-author Deepa Balsavar, founded the Sherpa Project to record oral histories through in-depth interviews of members of the climbing Sherpa community.

A well-known illustrator and storyteller, Deepa Balsavar has created more than thirty children’s books. She has won numerous awards, including Tata Trusts’ Big Little Book Award for her contribution to children’s literature, worked as a consultant with UNICEF in South Asia, and served as a core team member of the Avehi-Abacus Project for two decades. Balsavar is an adjunct professor in communication design at the Industrial Design Centre, IIT Bombay.