Exactly one year ago, Mayor Brandon Johnson used his inaugural address to paint a vibrantly optimistic picture of the city’s future, claiming a mandate from the “soul of Chicago” to make the city a more equitable place to live.

Showcasing his booming laugh and quick wit, Chicago’s 57th mayor gave no sign of the enormous pressure bearing down on him from all sides that would soon complicate his push to create a “Chicago for all” — not just the wealthy or the powerful.

From the left, the political movement that elected Johnson has pressed him to use his power to address crime, poverty, homelessness and other deeply entrenched problems spotlighted by the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic. From the other side of the political spectrum, the rookie mayor — who had never before served as an executive — faced harsh public criticism from power brokers who found themselves on the outside looking in.

“People put me in charge to change course,” Johnson told WTTW News. “And what is very clear, I say this with all due humility, people know we are changing course in this city. There should be no doubt in anyone’s minds that we are moving in another direction. I believe people are up for it. And I’m looking forward to the implementation of many of the things that we’ve already put forward.”

One year after his passionate inaugural address, and in spite of the challenges posed by the last 12 months, Johnson said he is even more optimistic about the city’s future, even as he acknowledged high-profile defeats, unfulfilled promises and looming challenges.

“It is clearly possible for us to build a better, stronger, safer Chicago together,” Johnson said, rattling off his 2023 campaign slogan that he has transformed into an oft deployed talking point. “I promised that I would invest in people and that there is more than enough for everyone. I’m still very much optimistic, and I’m confident that our collaborative approach will help us transform this city.”

Johnson said he was elected to reverse 40 years of disinvestment, particularly in the city’s public education system, and create systems to care for people. That is very much a work in progress — and there is plenty of time for that to start translating into real changes in Chicagoans lives, Johnson said.

“That’s what I’m counting on,” Johnson said. “As people in Chicago continue to have more favorable interactions with city government, when they have safe spaces where they can take their children for recreation, when they have fully funded schools, when they begin to see the benefit of the affordable homes that we are building. As long as people know that these are policies and promises that I made and that I’m keeping them, and they are a benefit to them, that is the satisfaction that is more than enough for me.”

Johnson said his confidence is bolstered by the successes he enjoyed during his first year in office, including his successful push to phase out the tipped minimum wage, ensure that Chicago workers get at least 10 days of paid time off and the approval of a $16.6 billion spending plan for 2024 that he said was designed to put a down payment on ending the “generational trauma” his predecessors inflicted on Chicagoans.

The city’s 2024 budget earmarked enough money to double the number of social workers, addiction specialists and counselors working to respond to 911 calls for help from people experiencing mental health crises and to open two new mental health clinics in facilities already operated by the Chicago Department of Public Health.

Those proposals are the core of the plan known as “Treatment Not Trauma,” which Johnson pledged to implement if elected mayor.

“Of course, I’d like to open up six (clinics) right now,” Johnson said, referring to the number of clinics closed in 2011 by former Mayor Rahm Emanuel. “The two (clinics) is a big deal. But of course I want things to move faster.”

Johnson’s first budget also grew the city’s youth jobs program by 4,000 positions to 28,000 jobs. More than 46,000 teens and young adults applied for the city’s summer jobs program in 2023, according to city records, leaving a significant deficit that Johnson has yet to address.

But Johnson did not use his news conference immediately following the 41-8 vote to approve the budget to celebrate the money set aside to fulfill his campaign promises and begin the work of shifting the city in a more progressive direction.

Instead, flanked by alderpeople who had expected to celebrate the lopsided victory, Johnson announced that migrants who make their way to Chicago will be limited to no more than 60 days in city shelters. That unexpected announcement shocked many of the mayor’s allies, as did his statement that he would not “sacrifice the needs of Chicagoans in support of those who wish to become Chicagoans.”

Johnson’s allies rebuked him both publicly and privately for making those remarks, and he never said anything like that again.

But that statement was Johnson’s most direct acknowledgement of the deep racial divisions exposed by the migrant crisis. Black alderpeople have said it was deeply painful to see the city spend hundreds of millions of dollars to care for the newest Chicagoans, many of them Latino, while they have lived in neighborhoods that have suffered from disinvestment for decades — with no end in sight.

At the height of the migrant crisis, critical parts of Johnson’s political base found themselves at odds, with progressive leaders demanding the mayor do more to care for the vulnerable migrants while many Black Chicagoans wanted to stop spending taxpayer money to house and feed the newest Chicagoans.

Johnson has yet to reconcile those competing pressures.

Education a Focus for Teacher Turned Mayor

Johnson has also quietly made significant changes to Chicago Public Schools as the district prepares to transition from mayoral control to an elected school board.

Johnson reversed the centerpiece of Emanuel’s education policy by ending student-based budgeting, which linked most of a school’s budget to its enrollment by giving each school a set amount for each student. Johnson also backed a push to remove police officers from schools and ended a contract first inked by Emanuel and continued by former Mayor Lori Lightfoot to privatize custodial services. All of those changes had long been demanded by progressive groups — and none were highlighted by Johnson in public events.

Johnson’s hand-picked board also launched an effort to implement the mayor’s promise to bolster neighborhood schools, which saw their budgets and resources shrink during the Lightfoot and Emanuel administrations while selective enrollment and magnet schools expanded.

That prompted a serious backlash from supporters of selective enrollment schools, which are some of the most high-performing in the state. A bill pending in the General Assembly would prevent CPS officials from closing any of those schools before the fully elected board is seated, despite the fact that there are no plans to close any schools.

Johnson said he was determined to make good on promises to “disrupt” Chicago’s status quo and represent the “whole of Chicago, versus parts of Chicago,” despite the blowback.

“You know something is changing,” Johnson said. “And that can be frightening for people, especially if that shift has been in the midst of what has been an unending storm for people, particularly on the West and South sides of the city.”

Johnson’s campaign platform vowed to levy $800 million in new taxes on the wealthiest Chicagoans to fund that shift, only to run into a brick wall of opposition. Johnson has yet to move to fulfill any of those promises, including plans to impose a $4 per employee tax on large companies or to seek state approval to add a $1 or $2 tax to each securities trading contract.

And voters rejected a Johnson-backed ballot measure known as Bring Chicago Home that would have given the Chicago City Council the power to hike taxes on the sales of properties worth $1 million or more to generate $100 million annually fight homelessness.

Immediately after the defeat, Johnson declared he would not scale back his “big, bold” progressive agenda, telling opponents to “buckle up.”

But months later, Johnson remained perplexed by the defeat.

“Everyone says out loud we have to address this crisis, but you can’t say we have to address it and then say we can’t invest to address it,” Johnson said. “It is counterintuitive they reject the means to address it.”

The opposition to the ballot measure was led by Chicago’s business and real estate community, many of whom backed Paul Vallas over Johnson in the mayoral runoff and fought Johnson’s efforts to end the tipped minimum wage and expand paid time off for employees. Much of the campaign worked to cement the narrative that Johnson, a former organizer with the Chicago Teachers Union, was anti-business.

“This notion somehow that I am hostile to business is make-believe,” Johnson said, pointing to his plan to streamline development approvals at City Hall, the agreement he brokered to move the renovation of O’Hare International Airport forward and his decision to earmark $151.2 million in taxpayer money to transform Chicago’s Financial District into a residential neighborhood amid the shift to remote work.

About a month after the defeat of Bring Chicago Home, Johnson won the City Council’s approval to borrow $1.25 billion during the next five years to fund a wide-ranging slate of projects designed to expand the supply of affordable homes and good-paying jobs.

Those funds are now central to Johnson’s efforts to fulfill his promise to expand the city’s economic capacity — without raising taxes on Chicago property owners, keeping another key campaign promise.

But the vote approving the borrowing was not without controversy, with several alderpeople — including two elected to represent downtown wards, which are among the city’s wealthiest — repeatedly trying to alter the proposal during the City Council meeting, in a public show of defiance.

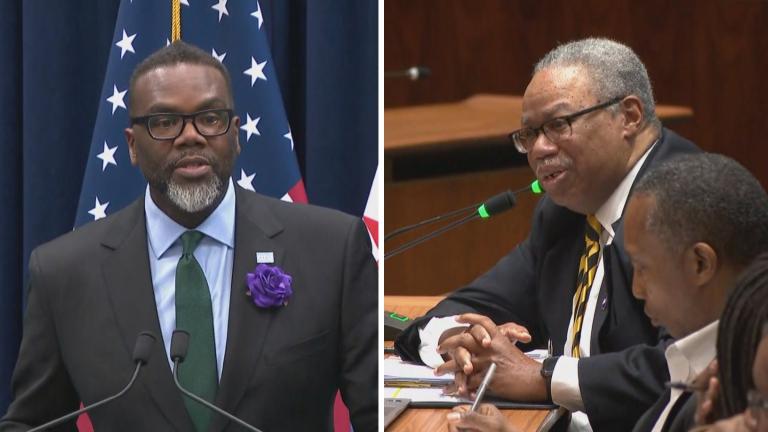

That clamor was so intense that it shocked even veteran members of the Chicago City Council like Ald. Walter Burnett (27th Ward), who is now the longest serving alderperson and Johnson’s vice mayor.

Burnett said the tumult reminded him of the period of time in the 1980s known as council wars, which saw a block of White alderpeople thwart the initiatives of the first Black man elected mayor, Harold Washington. Johnson is the second Black man to be elected Chicago mayor.

“It’s interesting that this only happens when there is a Black man up there,” Burnett said April 19.

Johnson told WTTW News he did not necessarily share Burnett’s opinion that the opposition he experienced was motivated by his race but noted that Washington was also elected to change the status quo.

“The more things change, in some instances, the more things stay the same,” Johnson said. “I’ve worked hard to bring some decorum to our debates. I’ve tried to model that. I’ve been collaborative, where other mayors have not been.”

Johnson’s approach to economic development signals the end of the city’s decades-long reliance on tax increment financing districts, known as TIFs, and will allow the city to provide assistance for new businesses, restaurants, affordable homes and cultural facilities not just in parts of the city where property tax revenue has been growing, but also where it has been stagnant or declining for many years — a reminder of the legacy left by modern segregation.

Those lasting scars also prompted Johnson to promise to put an end to what he called “literal sacrifice zones” — neighborhoods home to Black and Latino Chicagoans where industrial firms are allowed to pollute the air, water and soil with impunity, making residents sick and degrading their quality of life.

While Johnson’s first spending plan reestablished the Department of the Environment, he has yet to ask the City Council to approve an ordinance that would allow city officials to weigh the amount of existing air, water and soil pollution in a community — not just what a proposed project is expected to add if it is approved — when considering allowing additional polluting industries.

Progressive Agenda Crowded Out by Migrant Crisis

Thinking back to his inaugural address, Johnson acknowledged that he did not anticipate that the humanitarian crisis that had begun to grip the city with the arrival of thousands of men, women and children from the southern border, many on buses paid for by Republican Texas Gov. Greg Abbott, would soon spiral out of control, upending many of Johnson’s carefully laid plans.

Johnson said he was counting on Abbott “demonstrating at least some form of humanity.”

“If I could go back, I would tell myself that the governor of Texas is far more extremist than is being reported,” Johnson said.

During that speech, Johnson promised Chicago would welcome the thousands of migrants, all of whom are in the country legally after requesting asylum.

“There’s room in Chicago for everyone,” Johnson said, triggering a standing ovation.

In all, more than 41,000 people, many fleeing violence and economic collapse in Venezuela, have made their way to Chicago since August 2022, with nearly 90% of those migrants arriving after Johnson’s inauguration. That has strained the city’s social safety net, ballooned the city’s budget shortfall and exacerbated tension between Chicago’s Black and Latino communities.

Keeping his promise to honor Chicago’s status as a welcoming city proved to be far more difficult than Johnson thought, with Abbott quickly ramping up the number of buses sent to Chicago in an effort to thwart Johnson’s agenda, damage President Joe Biden’s chances for reelection and divide Democratic voters.

With Chicago’s shelters full, thousands of people were forced to sleep on the floor of police stations across the city and at O’Hare International Airport in often squalid conditions. It took city officials until December to open enough shelters to allow them to clear the police stations.

But the crisis was far from over.

Johnson’s plan to build massive, winterized tents to house the migrants, which drew immediate criticism from progressive leaders, never got off the ground. After Gov. J.B. Pritzker promised to use state money to build what came to be known as a base camp in Brighton Park, he pulled the plug on the plan after environmental tests showed the property was polluted.

That decision dealt a significant blow to the already cool relationship between Johnson and Pritzker, complicating efforts to care for the migrants.

Johnson also had no choice but to spend a significant amount of political capital to convince the City Council to earmark $271 million to care for the migrants.

“I’m not quite sure, quite frankly, if it would have changed our trajectory,” said Johnson, but added that Abbott was more “diabolical” than he and his advisers anticipated by sending tens of thousands of vulnerable people to Chicago.

Johnson expressed no regrets about how he handled the crisis, claiming credit for renegotiating expensive contracts inked by Lightfoot and working to build an “operation that is centered around people’s humanity” during an unprecedented crisis.

“It was a chaotic situation of which that we brought order and structure,” Johnson said.

But conditions at at least some of the city’s shelters were grim, with a 5-year-old boy who lived in the city’s largest shelter dying in December after contracting sepsis and several viruses. That same shelter became the epicenter of a full-blown measles outbreak that appears to have peaked at the end of March.

In mid-March, Johnson began evicting adults from the city’s migrant shelters who had been there longer than 60 days, prompting intense criticism from progressive leaders and groups.

Unlike the federal government, which has not responded to city officials’ pleas for financial help, Chicago lived up to its values, Johnson said.

“The people of Chicago have really stepped up,” Johnson said.

A New Vision for Public Safety

No issue dominated the 2023 mayoral campaign more than public safety, as voters demanded candidates address the surge of crime and violence that began during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and has yet to fully recede.

When he took office, Johnson faced entrenched skepticism from leaders of the city’s largest police union and City Council members who take pride in proclaiming that they back the Chicago Police Department.

Fraternal Order of Police Lodge 7 President John Catanzara told the New York Times on March 27, 2023, that if Johnson won there would be “blood in the streets.”

Instead, homicides dropped 15% during Johnson’s first year in office, according to a WTTW News analysis of police data. During Lightfoot’s first year in office, homicides dropped 6%, only to surge during the pandemic, while Emanuel saw a 21% spike in killings during his first year in office.

And Johnson’s decision to tap CPD veteran Larry Snelling to serve as the city’s top cop won plaudits across the political spectrum.

“There’s still a lot of work to be done,” Johnson said. “Do I want it to move with more expediency? Of course I do.”

The investments in economic development and affordable housing, now possible because of the bond deal, will move the needle significantly on crime and violence, Johnson said.

But for months, Johnson’s administration has been consumed by the issue of ShotSpotter, a fraught topic complicated by the mayor’s announcement he would terminate the contract just days before it expired, but allow the system to continue to operate until September.

However, there was no agreement between the city and SoundThinking in place to permit the extension announced by the mayor, leading to days of confusion and the eventual announcement that the contract would not end until November.

That confusion muted the celebration of progressive groups, many of which have long demanded an end to the city’s use of the system, and denied Johnson a victory lap.

It also emboldened City Council critics of the move, who are set to force a May 22 vote on an order that accuses Johnson of having “usurped the will of the City Council and their ability to represent constituents” by canceling the city’s contract with the controversial gunshot detection system.

Johnson has also yet to make good on promises to step up efforts to reform the way the Chicago Police Department trains, supervises and disciplines officers in an effort to restore the public’s trust in the beleaguered department, which has faced decades of scandals, misconduct and brutality.

Johnson acknowledged that he spent little time during his first year in office publicly focused on complying with the 5-year-old federal court order known as the consent decree.

Instead, Johnson said he and his public safety team worked behind the scenes on the reform effort, which is significantly behind schedule. CPD has fully met just 6% of the court order’s requirements, according to the most recent report by the team monitoring the city’s compliance with the consent decree released in November.

The monitoring team will weigh in on Johnson’s efforts in its next report, expected by the end of June, which “will include our assessment of whether the outcomes intended by the consent decree are being achieved and whether changes are necessary to expedite and sustain reform,” according to a statement from independent monitor Maggie Hickey.

“There is real work being done and there are all hands are on deck to see to it that our consent decree, that we are actually not just adhering to it, but we’re demonstrating how that adherence is creating safer communities,” Johnson said.

Slow and Steady Wins the Race, Johnson Says

Johnson acknowledged his own preference to focus not on the start of initiatives with high-profile events designed to capture public attention and the media spotlight, but to focus on actual accomplishments. That has left many supporters frustrated by Johnson’s reluctance to tell his own story.

“What I don’t want, and everyone knows this about me, and if they don’t, they should know by now, I won’t just simply show up at a groundbreaking,” Johnson said. “I’m about the ribbon cutting. I want to open the doors.”

Johnson said his job is to remain “calm, steady and focused” and “not distracted by some of the noise that might exude as a result of that anxiety” caused by Johnson’s push for change.

That noise reached a crescendo after Hamas launched a terror attack against Israel on Oct. 7. The City Council on Oct. 13 adopted a non-binding resolution condemning the attacks after a fiery debate that forced Johnson to clear the gallery of the public.

Three months later, Johnson cast the tie-breaking vote to approve a nonbinding resolution calling for a cease-fire after another fraught City Council debate. That vote damaged his relationship with some members of Chicago’s Jewish community at a time of rising antisemitism.

Johnson has also had to answer for controversies caused by his allies in the progressive movement, many of whom he elevated into positions of power.

Johnson has been without a permanent Zoning Committee chair and floor leader since November, when Ald. Carlos Ramirez Rosa (35th Ward) resigned from those leadership positions after apologizing to Ald. Emma Mitts (37th Ward) for a “disrespectful interaction” during a debate over Chicago’s status as a welcoming city.

Johnson cast the decisive vote to spare Ramirez Rosa from censure, ending weeks of tumult that distracted from Johnson’s spending plan for 2024.

A similar upheaval occurred in April, when conservative members of the City Council attempted to remove Ald. Byron Sigcho Lopez (25th Ward) as chair of the Housing Committee after he called for an end to the war in Gaza and denounced Biden for supporting Israel at a protest where an American flag was burned.

The effort to punish Sigcho Lopez failed, but it once again sucked up all the oxygen in the room.

Johnson said that is just the cost of trying to push Chicago toward a new course.

“When you have bold, progressive ideas that really get at the heart of our challenges and you are breaking away from the status quo and you are focusing your attention on everyone not just a handful of people who have had unfettered access to the 5th floor, but we’re talking about everyday people in the city of Chicago,” criticism is inevitable, Johnson said. “Those are the people that I think about every single day.”

As Johnson enters his second year in office, the obstacles facing him are only growing.

The CTA has yet to recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, with service lagging 2019 and persistent complaints about crime and cleanliness. Johnson’s progressive allies have stepped up efforts to oust CTA President Dorval Carter, ensuring the issue remains in the City Hall spotlight.

In addition, fate of the Chicago Bears’ plan to build a $4.75 billion domed stadium on the lakefront with $2.4 billion in public subsidies remains in limbo, with state officials far less enthusiastic than Johnson.

But no challenge is greater than the one posed by the arrival of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago on Aug. 19. Johnson has vowed the convention will showcase the best of Chicago and propel Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris to a second term.

The convention, which is sure to attract a wide range of protests, will test the Chicago Police Department’s ability to constitutionally police large gatherings protected by the First Amendment. Johnson said he and Snelling had “very candid conservations” about the convention.

“If there is a mayor who values protest, it is certainly me,” Johnson said. “I know what it is like to be out there demanding government respond to our hopes and aspirations.”

Contact Heather Cherone: @HeatherCherone | (773) 569-1863 | [email protected]