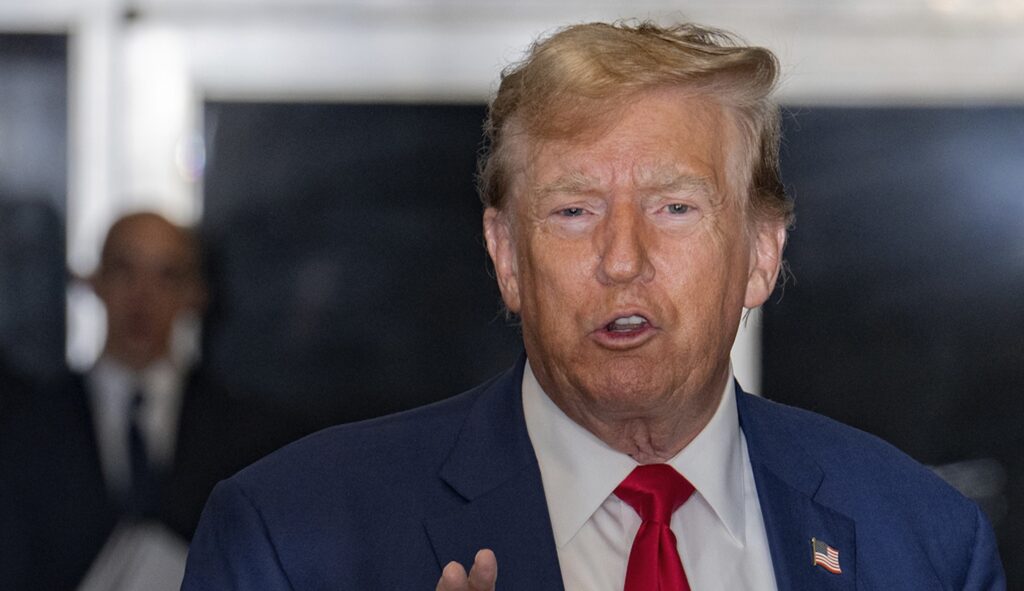

Former President Donald Trump’s four criminal cases have created an unprecedented legal gauntlet for him to run before voters have a chance to decide if he should return to the Oval Office. While Democrats cheer what they see as long-overdue accountability for the former president, some legal experts have expressed concerns that the cases — half are brought by partisan district attorneys, and the other half are overseen by the Biden Justice Department — are built on novel and unfair interpretations of the law. In this series, the Washington Examiner will take a look at the flaws that could unravel the cases against Trump. Part one will look at the Fulton County case.

Propped up by a risky legal structure in Fulton County, Georgia, the high-profile case against former President Donald Trump is encountering near-insurmountable hurdles as it remains marred in scandals and setbacks.

The sweeping Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations indictment, which initially charged Trump and 18 of his associates on Aug. 14, 2023, with alleged attempts to subvert the 2020 election results, is facing complexities that may delay the trial past the 2024 election. While many problems are procedural in nature, legal experts interviewed by the Washington Examiner say the merits of the case may also present problems for Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis.

Central to the prosecution’s strategy is Georgia’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a potent legal tool designed to combat organized crime. By structuring the case under this law, prosecutors aim to prove that Trump and his allies engaged in a pattern of criminal activities with a common purpose — in this case, an alleged effort to subvert Georgia’s election results.

“I think the fairest thing to say about it is it’s a unique case to use the RICO statute in terms of trying to overthrow an election or challenge the outcome of an election in a state,” said Matthew T. Mangino, a current defense attorney and former elected district attorney of Lawrence County, Pennsylvania.

Mangino told the Washington Examiner when RICO was first established in 1970 to target organized crime and white-collar crime, people “weren’t contemplating that this statute was going to be used to prosecute, to try to influence an election in some way.”

“So I think just the unique nature of it puts it in a position where there’s really no precedent for it. And so when you’re dealing with new and novel prosecutions, there’s always a risk,” Mangino added.

Where the case currently stands

Trump and his co-defendants were arraigned on Sept. 6, 2023, at the Fulton County jail. Soon after, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Scott McAfee, who is campaigning for reelection, was named to preside over the case.

So far, Trump attorneys Jenna Ellis, Sidney Powell, and Kenneth Chesebro and Atlanta-based bail bondsman Scott Hall have pleaded guilty in the case and were given reduced sentences in exchange for their cooperation with Willis’s office.

Hans A. von Spakovsky, a senior legal fellow at the Heritage Foundation, wrote in November that the plea deals Willis provided to the four defendants actually demonstrate “the weakness” of the case.

“The defendants were facing hundreds of thousands of dollars in attorneys fees to defend themselves before what would almost surely be a politically biased jury and a partisan prosecutor who has filed charges attempting to criminalize perfectly lawful activities—such as Mr. Trump’s ‘nationally televised speech’ claiming that he had won the 2020 election (Act 1 in the indictment),” Spakovsky wrote.

Of the 41 charges brought against the initial 19 defendants, Trump faced 13 charges, including a violation of the state racketeering law, or RICO, solicitation of violation of oath by a public officer, conspiracy to commit impersonating a public officer, conspiracy to commit forgery, conspiracy to commit false statements and writings, committing false statements and writings, conspiracy to commit filing false documents and filing false documents.

Before a trial has even begun, defendants have already succeeded in shaking off some of the charges levied against them.

McAfee on March 14 dismissed six of those charges, including three against Trump, saying prosecutors had not provided enough detail to support them. The dropped charges accused the defendants of soliciting public officers to violate their oaths.

The judge left open the avenue for prosecutors to either reindict defendants on the charges with more detail added or seek permission to appeal the ruling. However, doing so could further delay the already-stalled cases. Trump still faces 10 counts, and each carries a maximum prison sentence of between three and 20 years.

Meanwhile, Willis has asked the judge to begin a trial for all the remaining defendants, including Trump, by Aug. 5, 2024, but McAfee has not established a date.

Procedural delays and office romance eclipse case’s merits

In early January, a motion filed by co-defendant Mike Roman, a Republican political operative, sent Willis’s case haywire.

The allegations brought forth by Roman’s attorney Ashleigh Merchan were striking. Up until mid-January, most of the public was unaware of a long-standing relationship between Willis and her then-special prosecutor, Nathan Wade, an outside attorney she hired to handle the case. Since then, defendants have waged a robust fight to disqualify Willis from the case on the basis of an “appearance of impropriety.”

After a series of hearings that cracked open salacious details about the relationship between Willis and Wade, McAfee ruled on March 15 that Willis could continue to prosecute the case as long as Wade stepped down, citing an “odor of mendacity” stemming from the office relationship.

On May 8, the Georgia Court of Appeals announced it would consider Trump’s appeal of a ruling that allowed Willis to stay on the case, dealing prosecutors another blow.

“Fani Willis is having great difficulty in moving the Georgia case forward,” Tre Lovell, a Los Angeles trial attorney, told the Washington Examiner, adding that the Georgia Court of Appeals decision to reconsider McAfee’s ruling “means the likelihood of a trial occurring before the election happens is very unlikely.”

A hearing date has not been slated for the appeal, but several of Trump’s co-defendants, including former Georgia GOP head David Schafer, Mark Meadows, Rudy Giuliani, Cathy Latham, and Roman, all filed their notices of appeal on Monday.

Charging under Georgia’s RICO law was always a double-edged sword

Legal experts told the Washington Examiner if the case ever does head to a trial, Willis could face an uncharted set of hurdles based on the uniqueness of her case.

Georgia’s RICO law is unique in that it gives prosecutors broader leeway to charge certain acts under an indictment that the federal law does not allow, according to Nicole Brenecki, a New York-based attorney.

“I think that this was a strategic move in order to be able to have that sweeping indictment that has so much more it’s like a big dive in but as we know, it’s all been falling apart very slowly,” Brenecki said.

Lovell similarly indicated that pursuing “a RICO case against 15 defendants on the facts presented will be an excruciating uphill battle.”

“This is a case that not only should have been avoided because of its own merit challenges, but also because the Jack Smith Jan. 6 federal prosecution involves very similar issues,” Lovell added.

The four-count federal indictment against Trump is awaiting an extraordinary decision by the Supreme Court over whether the former president enjoys absolute immunity from prosecution. Not much is known about how the justices will rule, but if their oral arguments offered any hint to the answer, they could send the case back down to the lower court for additional fact finding to determine whether any actions Trump undertook were within the scope of presidential duties.

If the Supreme Court does rule sometime in June to send the federal case back for more fact finding, the same could happen in McAfee’s courtroom, according to Georgia State University law professor Anthony Michael Kreis.

“There might be some tricky questions, but I think, by and large, that the key factual allegations of wrongdoing — encouraging the governor and former Speaker of the House [David] Ralston to convene the General Assembly to overturn the election, engaging in harassment of poll workers, brow-beating [Secretary of State] Brad Raffensperger — are easily outside the official duties of the president,” Kreis told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in a recent interview.

McAfee would likely have to look at other overt acts listed in the indictment that Fulton County prosecutors say were outside the perimeter of the presidency, but that might fall under any narrow immunity protections suggested by the Supreme Court. For example, Act 22 of the indictment claims a simple six-word tweet from Trump on Dec. 3, 2020, was “in furtherance of the conspiracy.”

“Georgia hearings now on @OANN. Amazing!” Trump tweeted in reference to hearings held by the committees of Georgia’s state Legislature, where Trump allies promoted claims of mass election fraud to convince the legislature to overturn the results. The full indictment lists 12 tweets Trump posted that prosecutors say furthered the alleged election subversion conspiracy.

Meanwhile, numerous experts also said that the delays mean the case may not take place until next year. If Trump is elected, it is not clear whether he would even remain part of the case at that point. The question as to whether a sitting president could be tried in state courts might ultimately become another lofty question for the Supreme Court to tackle.

Mangino said he struggled to picture how the case would suddenly end for the other remaining defendants merely because “one of the defendants will be unavailable for four years” but said the question surrounding whether Trump could still be tried as president would “be a contentious issue.”

“Willis started a case that she is going to have to finish, even if it’s not as salacious in the end as she was hoping for,” Brenecki said.

Trump, Willis, and McAfee all face their own campaigning obstacles amid a rush to a trial

Trump has repeatedly cast the four indictments he faces in the lead-up to the November election as an “election interference” operation by President Joe Biden and his Democratic allies.

But the effort to race the Georgia case to a trial is having its own interference problems on McAfee and Willis, who are both facing reelection bids for their coveted positions this year.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Since early March, McAfee has attended more than 30 campaign-related events, including fundraisers, candidate forums, church services, and parades. The cost of campaigning has resulted in “delaying every aspect” of his job, he told the New York Times on Wednesday.

Willis has also been campaigning to secure her reelection as the county’s district attorney, though it’s not apparent her campaigning is the reason for any additional delays because the county typically relies on additional personnel to handle the Trump case in the courtroom.