by Jerry Cayford

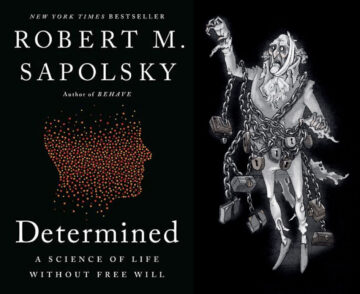

Robert Sapolsky claims there is no free will. Jacob Marley begs to differ. Let us consider their dispute. Sapolsky presents his case in Determined: A Science of Life Without Free Will: everything has a cause, so all our actions are produced by the long causal chain of prior events—never freely willed—and no action warrants moral praise or blame. He supports this position with a great deal of science that was not available back when Marley was alive, though “alive” seems an awkward way to put it, since Marley is a fictional ghost, possibly even a dreamed fictional ghost (depending on your interpretation of A Christmas Carol), dreamed by fictional Ebenezer Scrooge. Marley’s standing to bring objections against Sapolsky seems pretty tenuous.

Nevertheless, Marley forthrightly rejects Sapolsky’s thesis: “‘I wear the chain I forged in life,’ replied the Ghost. ‘I made it link by link, and yard by yard; I girded it on of my own free will, and of my own free will I wore it.’” That there is a real dispute here is proven by Scrooge presenting a very Sapolskian argument against Marley’s right to bring a case at all: “You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato.” That is, only a chain of physico-chemical causes makes me, Scrooge, see you at all, let alone give any credence to your arguments about morality. If this rebuttal seems sophisticated for a fictional Victorian businessman, it at least reminds us that Sapolsky’s philosophical position is quite old and well known.

Unlike Scrooge, Sapolsky does not inhabit the same fictional realm as Marley’s ghost. He cannot argue that Marley’s sins were caused by prior conditions and events, because Marley’s sins and choices don’t really exist, not in the causal universe in which Sapolsky makes his argument. As he so emphatically puts it: “But—and this is the incredibly important point—put all the scientific results together, from all the relevant scientific disciplines, and there’s no room for free will.…Crucially, all these disciplines collectively negate free will because they are all interlinked, constituting the same ultimate body of knowledge” (8-9). Marley’s ghost, though, is not of that body—an “incredibly important point” indeed—and that’s precisely the reason to choose him as our spokes-“person.”

As we would expect from a world-famous scientist and prolific science popularizer, the science part of Sapolsky’s book is solid, interesting, and entertainingly told. His philosophy part is iffier. But since the philosophers will turn out to have their own problems, let’s approach this science-versus-philosophy issue from outside of both: with literature. How are we to make out Marley’s case? I have already quoted the whole of what is in Dickens’s text, a bare assertion of Marley’s claim to free will. We’ll need more than that. We must engage in a speculative exercise, then, about what a fictional character would believe or would say. This is nothing nefarious, and most literary analysis is some form of this exercise. It is a discipline and has a logic. For anyone unfamiliar, though, an excellent introduction is this Saturday Night Live sketch in which an actress (played by Emma Stone) with a bit part in a gay porn film tries to establish her character’s motivation (as actors put it), i.e. the events of her character’s life not in the script that inform what she does say in the script. We can take a four-minute recess for you to watch it now.

Interestingly, we again find a Sapolskian rebuttal in the mouth of one of the fictional characters. The porn director specifically rejects the very exercise in question, claiming that nothing exists that is not in the script (the script being equivalent in his fictional world to the ultimate body of interlinked knowledge in Sapolsky’s): “She has no past, no future; she only exists to be cheated on.” The porn director’s reliance purely on the script is close in spirit to the reductionism so central to Sapolsky’s project—“Reductionism is great” (239); “the central concept of science for centuries” (128). The objections of Scrooge, the porn director, and Sapolsky notwithstanding (Sapolsky doesn’t seem to be keeping very good company), the fictional actress and fictional Marley’s ghost are making claims on which Sapolsky’s great causal chain has no purchase. Their sins and backstory are imaginary and uncaused.

Let’s consider how far imagining might get us. Scientists are probably not fazed by the dreams and speculations of fictional characters, but what about imaginary numbers? They, too, proceed from a pure fiction: we know absolutely that negative numbers cannot have a square root, yet we imagine a square root for minus one (-1) anyway, call it “i” and see what we can do with it. We build imaginary numbers out of i, add imaginary numbers to real numbers, call these mixed sums “complex numbers,” and build an entire branch of mathematics called “complex analysis.” (It is the specialization of my mathematician father.)

Now, the reality of numbers is a vexed and venerable philosophical question. But whether real numbers are real or not—meaning whether real numbers (the ones we all know) are part of Sapolsky’s ultimate, interconnected body of science—imaginary numbers are definitely not real. It turns out, though, these totally nonexistent and impossible numbers have many valuable applications in electrical and audio engineering, fluid dynamics (pumping oil; earthquakes; weather prediction), and anything involving periodic motion. Who knew imagination was so vital?

I was led to Sapolsky’s book by David Kordahl’s article here on 3 Quarks Daily some months back. Kordahl picks up on Sapolsky’s incidental use of pragmatist philosopher William James, and ponders some of James’s thoughts on determinism (about which he wrote quite a bit). I would like to push further in that pragmatist direction. We have been tinkering around outside of Sapolsky’s “seamless continuum leaving no cracks between the disciplines into which to slip some free will” (240). Let’s go now to that continuum’s seamlessly interlinked center.

Science is based on observing. So, how does an observation work? Consider a quintessential observation: “the cat is on the mat.” Suppose we live in a village, and various vermin invade our houses, but we chase them out. Chatting at the market, we find all of us have allowed one vermin to stay, because it usefully chases away or kills other vermin. We call these useful ones “pets,” and notice that they come in black, white, and reddish brown, which we call “cats,” “dogs,” and “widgets,” respectively. (We reject multi-colored pets as devil’s spawn.) Over time, some people find these categories confusing and others don’t, depending on what their pets and their friends’ pets are like. Some people start reforming the usage, calling the purring carnivores “cats” and the purrless omnivores “dogs,” regardless of color. Other people stick to the traditional categories.

Now, Bowser (a black Labrador, as we would call it) is sleeping on the welcome mat. “The cat is on the mat”: true or false? It depends on what “cat” means. To traditionalists (for whom Bowser, a black pet, is a cat), the observation is true; to reformists (for whom Bowser, a purrless omnivore, is a dog), it is false. Who is right? We are up against the hoariest of philosophical problems: the problem of universals. Fluffy and Meow-meow, Bowser and Fido all exist—wholly regardless of humans. They are made of physical structures and chemical compounds; they were produced by prior causes going back to the beginning of time. They are “particulars” and are part of Sapolsky’s seamless continuum. But “cats” and “dogs” are “universals,” labels for groups of particulars; they are just groupings made up by the villagers for pragmatic reasons. That is, cats and dogs are fictions, like Marley’s sins, the actress’s backstory, or the square root of minus one.

And now everything unravels. Let’s pause before it does to put our narrative in a larger context. What is inside or outside the causal continuum, and why, are questions with a long history.

Sapolsky’s book applies interesting new science to a philosophical question of free will and determinism. If philosophers have been underwhelmed, it is because this new science says nothing new about very old philosophy. Sapolsky acknowledges as much when, after explaining a lot of new science on the brain’s activity in the milliseconds before forming a (supposedly free) intention, he says, “these minutiae of milliseconds are completely irrelevant to why there is no free will” (45). Rather, his real argument is that the causes of any intention go back hours, years, generations, millennia. And that claim is not a scientific discovery at all but a postulate, a postulate that philosophers have been working with for 2,500 years, ever since Democritus and Leucippus (originators, also, of the idea of “atoms”) first proposed it: “Nothing occurs at random, but everything for a reason and by necessity.” Sapolsky is doing straight philosophy, without any real help from science.

This idea of the universe as one giant causal mechanism kicks around for 2,000 years before it comes to dominate in the modern, scientific era. With nods to Descartes, Galileo, and Hobbes (1640-ish), the “clockwork universe” is mostly associated with Newton (Principia, 1687). Yes, as Sapolsky says, “It’s virtually required to start this topic with…Laplace” (15), because Laplace gave a famously catchy image for determinism (“Laplace’s demon”) in 1814. But that understates both the longevity and the dominance of determinism in the modern era. The crucial feature of this determinist cosmology is the cozy connection it makes between reality and knowledge; Sapolsky’s great seamless causal continuum stretching unbroken to the beginning of time is reality itself, and he can treat it as interchangeable with “all these disciplines…interlinked, constituting the same ultimate body of knowledge” (9) only because modern realist science and philosophy presume that knowledge “corresponds” to reality, i.e. that knowledge (truth) is pretty much just reality in a different form, the form of words.

Now the unraveling. If cat, the universal, is a fiction, then so are observations like “the cat is on the mat,” and so are the sciences made of those observations. The problem of universals is the problem of the relation between language and reality, and it is a mighty problem lying squarely between the two. How can we villagers, simply agreeing on whatever labels seem useful for discussing our household vermin problems, somehow bind ultimate reality to our words? Going back to the ancient pre-Socratics again (Parmenides, this time), one influential view was that we cannot: Being or the One (which we familiarly demote to “reality”) is not even thinkable, let alone knowable. On Parmenides’s chariot journey of understanding, guided by maidens from the House of Night to the parting of the paths of Truth and Opinion, where Justice holds the keys to both gates (I love the pre-Socratics!), the material world we observe is all part of the Path of Opinion. In any case, “the cat is on the mat” and all the truths of science occur in language made of universals that are—like Marley’s sins—outside the seamless causal continuum.

But can’t we just say that scientific knowledge doesn’t have to be “part of” causal reality; it just has to describe reality? Isn’t it misleading to call universals “fictional” if they meaningfully designate something real? Aren’t the cats above “fictional” only because the villagers haven’t settled the term’s meaning? Sure, the word “cat” is arbitrary, a convenience, but once it has a meaning it picks out real, physical particulars, and so does the observation: “the carnivore that purrs and has these other properties…is on the mat.” Can’t we bind the label “cat” to reality by defining it consistently? Okay, but how?

Unfortunately for the cozy connection between truth and reality, the way we define universals is with more universals. Those who have read Sapolsky’s book probably know where I am going: turtles.

Sapolsky tells an anecdote on page one that he uses repeatedly throughout the book. It is crucial to the structure of his argument. William James (Sapolsky’s “fall guy” in the anecdote) is afflicted by a critic who argues that the Earth rides on the back of an elephant. Where is the elephant standing? On a giant turtle. Where does the turtle stand? On another turtle. And that one? “It’s no use, Professor James. It’s turtles all the way down!” (1) Sapolsky, though, gives a twist to this old story (emphasizing its importance to him): “Here is the point of this book: While it may seem ridiculous and nonsensical to explain something by resorting to an infinity of turtles all the way down, it actually is much more ridiculous and nonsensical to believe that somewhere down there, there’s a turtle floating in the air” (2). Sapolsky’s twist is to point out that an infinite regress, although it may seem incomplete and psychologically unsatisfying, is infinitely superior to an arm-waving evasion that pretends to have answered what it hasn’t.

Back to the cats. If a universal is tied to reality by its meaning—purring carnivore, etc.—then how did “purr” and “carnivore” get meaning? What words are they standing on? More words. And those ones? It’s no use, Professor James! Here is the point: while defining words with more words will never get the whole stack of them tied to reality (they will always stay “fictions”), it is truly ridiculous and nonsensical to think that somewhere down there, some words somehow, naturally, bind themselves to reality; then—“Abracadabra!”—those founding words at the bottom enable us to define other words, and so on back up the stack, until all of them are non-fiction reality!

The mainstream of modern philosophy wishes away the problem of universals with a magic word: “correspondence.” A true statement “corresponds” to reality. This purported connection between words and reality is reminiscent of the joke about economists—“assume a can opener!”—or Molière’s “dormitive power,” his spoof explanation of how soporific drugs work; as Sapolsky puts it, “magical explanations for things aren’t really explanations” (239). His turtle anecdote beautifully captures this kind of thinking as the pure nonsense of a stack of turtles floating in air. In such cases, the better answer is “turtles all the way down.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein gives a better answer, in the spirit of James’s pragmatism. Rejecting the idea that universals label bits of reality to which they correspond, Wittgenstein instead explains categorization through what he calls “family resemblances.” In so doing, according to Renford Bambrough, “Wittgenstein solved what is known as ‘the problem of universals.’” Bambrough himself illustrates family resemblances with the example of “the Churchill face” (no doubt more evocative to his audience than to mine): ten facial features subjectively similar among the famous family’s members; each feature further analyzed into its own properties, again grouped by subjective resemblances; and so on, leading to the conclusion that “there is a good sense in which no two members of the Churchill family need have any feature in common in order for all the members of the Churchill family to have the Churchill face.” Defining features (universals) just dissolves them into their parts, which then dissolve into subparts, and so on forever. No feature’s definition is ever completed, and yet people can still group them by similarity. That is, all universals, all concepts, are turtles all the way down, and all the turtles are just whatever seems subjectively sensible to a community of people.

The thing about turtles all the way down is that an answer is always deferred. Sapolsky is surely right that endlessly deferring is better than a question-begging, arbitrary answer that hangs in the air; yet some question is still never answered. In this case, what’s endlessly deferred is the question of truth’s ultimate relation to reality. I suggest we can afford to defer that question, since we don’t need it to explain meaning, truth, and science. Perhaps Sapolsky would agree, though it will cost his argument its elegant simplicity.

What started out as a fanciful fiction—Marley’s ghost—has grown through the actress’s backstory and the fiction of negative square roots to the meanings of all words. What has unraveled is that tight connection that we in our scientific era take for granted between reality and language. Instead, there is a moment of fiction at the heart of meaning, observation, science, truth. The edifice of human knowledge can still be built from processes like the villagers categorizing pets, but it appears now in a different light: not as one seamless body of knowledge but as a patchwork body stitched together from parts.

Sapolsky uses his turtle anecdote in arguing that acts of free will are a nonsensical explanation for our actions. I have adapted his turtles to a use he did not intend: illustrating how the problem of universals separates knowledge (science) from that seamless causal continuum he relies on to show “There’s not a single crack of daylight to shoehorn in free will” (9). Scrooge, too, locked securely in his dark rooms, thinks there’s not a single crack, as he listens to Marley’s ghost clanking up the stairs: “‘It’s humbug still!’ said Scrooge. ‘I won’t believe it.’ His colour changed though, when, without a pause, it came on through the heavy door.” Reality itself may have no cracks, but truth and knowledge are created out of acts of fiction, and those acts are full of daylight.