Pune: Pune has been a Brahmin citadel since the 18th century when it was the seat of the Peshwas — powerful Brahmin ministers who controlled the Maratha confederacy. It’s this history of the city — and the associated Brahmin pride — that helped the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), often described in the past as a “Brahmin-Baniya” party, take root and grow in Pune.

However, Pune’s mutating demographics have wrought a change in its political dynamics, with the city no longer being the Brahmin bastion it once was. This has put the BJP on a sticky wicket — while the party seeks to move with changing times, it comes at the cost of upsetting its biggest champions.

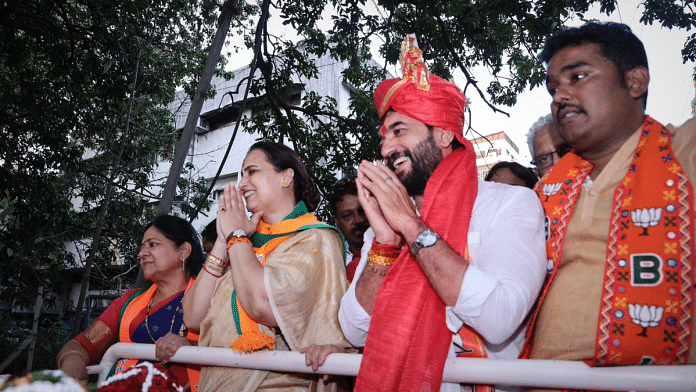

The root of the problem is what Brahmins in the city see as a lack of representation in public space. The BJP’s candidate for this election is former Pune mayor Murlidhar Mohol — a Maratha leader. Mohol will take on the Congress’s OBC leader Ravindra Dhangekar in the fourth phase of the polls, scheduled on 13 May.

The city’s Brahmins are upset at the party’s choice, which came just a year after a similar row over a bypoll in Kasba Peth — an assembly segment under the Pune Lok Sabha constituency. To placate its core vote bank, the BJP nominated former Kothrud MLA and Brahmin leader Medha Kulkarni for a Rajya Sabha seat this February.

But even that appears to have made little difference. Vicky Dhadphale, general secretary of the Akhil Bhartiya Brahman Mahasangh, a community association, minced no words as he voiced his displeasure.

“The Brahmin community is upset,” he told ThePrint. “We feel that if we can’t get representation in Pune, then where will we get it?”

While the Akhil Bhartiya Brahman Mahasangh previously campaigned actively for the BJP, it has decided to stay away this time.

“We have hence asked the community to vote for the candidates they want to,” he said.

According to political analyst Hemant Desai, parties are increasingly looking for non-Brahmin faces for Pune given the city’s changing demographics.

“Since the 1990s, Pune started becoming more and more cosmopolitan. People come to Pune for employment and education. Many people (are) from the north, and within Maharashtra, a lot of people from Marathwada have been coming to Pune,” he said.

On its part, the BJP concedes that there had been some anger among the Brahmins after the Kasba Peth bypoll but insists that this has now been pacified.

“The BJP is a disciplined party that accepts what the leadership gives us and moves forward,” party leader and Rajya Sabha MP Sanjay Kakade told ThePrint.

From Brahmin domination to mixed bag

Pune is an urban constituency with an increasingly cosmopolitan population. According to estimates by political parties, it has a sizeable presence of Brahmins and Marathas, with the two caste groups having near-equal numbers.

Besides this, the 2011 census also shows that the district that the Scheduled Castes make up 12.5 percent of Pune district’s population and Muslims account for 7.14 percent.

There are six assembly seats under it: Vadgaon Sheri, Shivajinagar, Kothrud, Parvati, Pune Cantonment (SC), and Kasba Peth. Of these, the BJP currently has four seats — Shivajinagar, Kothrud, Parvati, and Pune Cantonment (SC) — while the Congress holds one, Kasba Peth.

Meanwhile, Vadgaon Sheri is currently held by the Ajit Pawar-led Nationalist Congress Party.

The city has been home to several significant Brahmin leaders, among them descendants of the freedom movement icon ‘Lokmanya’ Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Girish Bapat, and the Gadgils — Kakasaheb Gadgil, his son and former minister V.N Gadgil and grandson and Anant Gadgil.

While the Tilaks and the Gadgils are known Congress loyalists, the late Girish Bapat, who was Pune’s MP until his death in March last year, was with the BJP.

Until about five decades ago, Pune was a Brahmin-dominated constituency. Congress heavyweight V.N. Gadgil won the seat thrice, beating Nanasaheb Gore of the Janata Party in 1980 and later trouncing the BJP’s Jagannath Joshi and Anna Joshi in 1984 and 1989, respectively.

From 1984 — when the BJP began to emerge as a dominant player in Pune — until 1996, the party fielded four Brahmin candidates, including Jagannath Joshi and Anna Joshi.

In 1991, Anna Joshi defeated Gadgil by 16,938 votes to win the seat for the BJP for the first time.

In 1998, an alliance of the BJP and the then undivided Shiv Sena decided to support Congress leader and then sitting MP Suresh Kalmadi, who was contesting as an independent. Kalmadi, a leader who traces his roots to Karnataka and who would eventually go on to face corruption allegations in connection with the 2010 Commonwealth Games, lost the polls to the Congress’s Tupe Vitthal Baburao by 93,218 votes.

According to data from the Election Commission of India, the BJP’s vote share in Pune has more than doubled in the past three decades. From 24 percent in 1991, it went to 29 percent in 1999, 55 percent in 2014, and 61 percent in 2019.

Since the late 1990s, there has been a perceptible shift in the party’s candidate selection.

From 1999 to 2014, the BJP fielded Rajput and Maratha candidates for the Lok Sabha elections. Rajput leader Pradeep Rawat won the 1991 election from Pune but lost the seat in 2004 to Kalmadi, by then back in the Congress. Kalmadi also beat Maratha leader Anil Shirole in 2009, but the latter managed to wrest the seat in 2014.

Meanwhile, the BJP tried to balance this by having a constant Brahmin representation for the Kasba Peth assembly seat. This strategy changed in the bypoll last March, when it picked OBC leader Hemant Rasane, who lost to the Congress’s Dhangekar.

The BJP’s decision to pick Rasane came four years after the party decided to drop its then sitting Kothrud MLA Medha Kulkarni and go with Maratha leader and Kolhapur native Chandrakant Patil. Although Patil won the election, the surprise decision added to the Brahmin ire.

All this anger spilled over just before the Kasba Peth by-poll, when anonymous posters that sprung up all over the constituency questioned the BJP’s candidate choices.“Kulkarni lost her constituency. The Tilaks lost their constituency. Now is it Bapat’s turn?” one poster asked.

Bapat died that same month. To many, Mohol’s candidature makes that poster prophetic.

“The Brahmin samaj is very angry and you will see that somewhat getting reflected in the votes,” Anand Dave, a Gujarati Brahmin leader and president of the Hindu Mahasangh, told ThePrint. “If you give one representation in Rajya Sabha (to Kulkarni) but get MLAs from other communities, it won’t help.”

The BJP, however, says these concerns seem to be from a standpoint of social compulsion rather than political understanding.

“These are social outfits representing the Brahmin community and not political groups,” said BJP spokesperson Kunal Tilak. “So, it’s natural for them to get upset. But Pune is a large constituency and the candidate having a better chance of winning gets the ticket.”

Still, the BJP is making efforts to reach out to its Brahmin voter base. In April, Chandrakant Patil and several senior BJP leaders held meetings with Brahmin outfits to rally support for Mohol.

But it isn’t just the BJP that’s moving away from Brahmin candidates. From picking Kalmadi in 2004 and 2009 to fielding Maratha leader Vishwajeet Kadam in 2014, this shift is visible in the Congress too, much to the chagrin of some of its Brahmin leaders.

“The condition of Brahmins in the Congress is like that of the Muslims in the BJP,” said former MLC and Congress leader Anant Gadgil.

A second Congress leader agreed, saying that the party prefers “OBCs and other communities over Brahmins”. That change in perception is reflected in the Congress’s pick for the Lok Sabha too, added this leader — also Brahmin.

“The state leadership also feels that Dhangekar can repeat his Kasba performance, but let’s see,” the leader said.

However, sociologist Shruti Tambe believes that it would be wrong to reduce Pune to being a Brahmin citadel. She emphasises that it belonged as much to social reformer Jyotirao Phule as it did to the Peshwas.

“Since colonial times, Pune has given voice to people of all castes and communities. Secondly, it is the bastion of the non-Brahmin movement since the British era. Post-independence too, Pune’s growth as an industrial and educational centre has been on the back of all communities,” said Tambe, a professor of sociology at the Savitribai Phule Pune University.

Multiple factions, infighting

The Pune parliamentary seat has been vacant since the death of Girish Bapat last March. The Election Commission didn’t call for a by-poll, and the BJP, which had multiple claimants for the same seat, also didn’t push for it.

In December, the Bombay High Court ordered the Election Commission to hold the election immediately. “The ECI is not only vested but charged with the duty and obligation to hold elections and see to it that any vacancy is filled in. The ECI cannot let a constituency remain unrepresented. Voters cannot be denied this right,” the court had said.

The Supreme Court, however, stayed this order on the Election Commission’s appeal. In its arguments, the EC said holding a bypoll was a “futile exercise” given that Lok Sabha elections were months away.

Meanwhile, three BJP claimants — party ex-national secretary and former Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) pracharak Sunil Deodhar, former Vadgaon Sheri MLA Jagdish Mulik, and Mohol — had already begun to campaign for the polls.

The party’s decision to field Mohol may have put paid to the others’ aspirations. However, according to party leaders, it also set off infighting within the Pune unit. “Senior leaders were overlooked as Mohol was close to senior state leaders,” one BJP functionary told ThePrint.

Hours after Mohol’s candidature was announced on 14 March, Mulik tweeted to express his gratitude to his supporters. He did not, however, congratulate the candidate.

जनतेच्या सेवेत कायमच!

कोणतेही पद नसतानाही माझ्या साठी जनतेने कार्यकर्त्यांने दाखवलेले प्रेम पाहून मी कायमच कृतज्ञ आहे.

जनतेचे प्रेम आणि विश्वास पारदर्शक, स्वच्छ काम असेच कायम ठेवणे ही माझी जबाबदारी आहे जी मी पूर्ण निष्ठेने पार पाडणार आहे.

पुन्हा एकदा तमाम जनता आणि… pic.twitter.com/izbXGXEPoh

— Jagdish Mulik (Modi Ka Parivar) (@jagdishmulikbjp) March 14, 2024

According to party leaders, Mulik is now campaigning for Mohol. This came after he met Maharashtra Deputy Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis in March.

Despite the BJP’s attempts to keep its house in order, on the ground, this election campaign is more subdued than usual. A senior party leader puts it thus: “He (Mohol) is an ex-corporator, yes. And he was also the mayor. However, some of us here have been MPs and MLAs and have served in better positions… So it is becoming a bit difficult to go out and campaign for him. But what to do, we have no choice.”

(Edited by Uttara Ramaswamy)

Also Read: Vacant, white-haired villages & ‘money order economy’ — how development eluded Ratnagiri